Meet ÌFÉ, The Puerto Rican-Based Group Singing Songs Of Decolonization

Listen to “Bangah,” a call for freedom, from their forthcoming debut album, IIII+IIII.

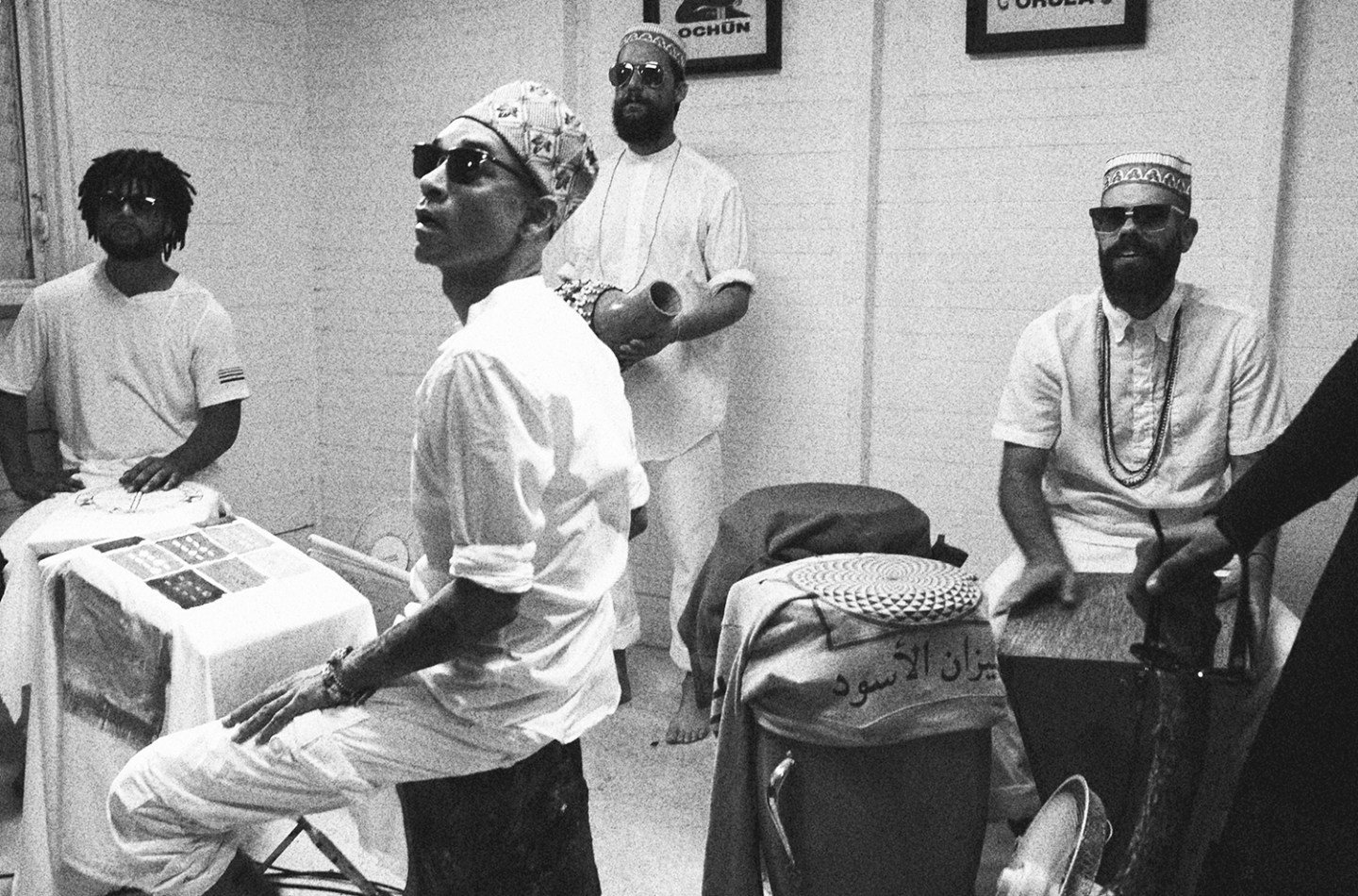

ÌFÉ

Mariangel Gonzales

ÌFÉ

Mariangel Gonzales

On their debut album, ÌFÉ crafts electronic drum loops that pay homage to a Black ancestral family. The Puerto Rican-based group’s IIII+IIII — pronounced “Eji-Ogbe” and due out March 31 — is a nine-track record that marries Yoruba praise songs with soul and hip-hop influences to create an expansive Afro-Caribbean groove. Much like previously released music, this album is grounded in Ifá — one of the branches of Santería, a syncretic Yoruba and Catholic faith practiced throughout the Caribbean. The Ifá practice is rooted in a binary divination system which inspired the album title.

Forming in 2015, the group is headed by Santurce-based producer Otura Mun, who is also a babalawo or high priest in the Ifá religion, and includes a large cast of local singers and dancers — Rafael Maya Awo Ejiogbe, Anthony Sierra, Beto Torrens, Yarimir Cabán, Jorvian Santana, and Walian Sánchez. With a not dissimilar mix of influences as electronic duo Ibeyi, ÌFÉ fuses the songs and concepts of Ifá and Ochá, with lyrics in English, Spanish, and Yoruba. Last year, the group dropped their first two singles, “3 Mujeres (Iború Iboya Ibosheshé)” and “House of Love (Ogbe Yekun),” which featured polyrhythmic patterns and deep synths that create trance energies inspired by Cuban rumba.

The ceremonial aura of ÌFÉ — an undeniably large part of their appeal — can be understood best through their “House Of Love” music video. Released in early 2016, the video features Otura Mun dressed in all white, drumming alongside other percussionists and juxtaposed by coded imagery and symbolism found in Ifá. The decision to so publicly incorporate parts of his spirituality in his music is potentially a heavy one for a wider Afro-Latinx community. Today there are growing public discussions of brujería (practices associated with “witchcraft”), curanderismo (a system of beliefs and rituals that address healing), Santería, and other Afro-Latinx practices linked to the spiritual world (for example, the New York skate collective BRUJAS recently trademarked their name). Yet, these conversations go against a traditional secrecy that surround many practices, including Ifá. A direct result of the trans-atlantic slave trade, the religion was historically practiced in secret because it was criminalized by settler-colonial forces. Otura Mun’s unconventional position in this space is important to note, as it brings up complex and painful questions relating to culture shift, belonging, and diaspora.

An African American from Indiana, Otura Mun moved to Puerto Rico in the late 1990s and has since grown to understand the connections between his own Blackness and the Puerto Rican colonial position. Having been witness to Puerto Rico’s gentrification, systemic poverty, and now the new oversight board — introduced by Obama in an attempt to solve the $70billion debt crisis — Otura Mun strives to use his music to address sociopolitical struggles on the island. The newest single from IIII+IIII, “Bangah,” premiering below, explores ideas of freedom and confrontation through upbeat electronic production that pulls heavy influence from Ogún, one of four Yoruba deities that are referred to as the warriors. It comes just weeks after the 100-year anniversary of Puerto Ricans gaining United States citizenship — a policy designed to bolster the United States military while maintaining a colonial hold on the island.

Over the phone from the tropical, metropolitan city of Santurce, I spoke to Otura Mun about the beginning of his musical journey, his unique relationship with Ifá, and the future of Puerto Rico.

Tell me about “House of Love.” It was the first song I heard from you and I remember the sound instantly resonating with me.

“House of Love” was the second song we put together as a group. I had been conceptualizing the group ÌFÉ and what I wanted to do with the music building off of the word ÌFÉ itself for a couple years. When I finally doubled down and bought the gear I needed to do it, it was a bit of a gamble because I didn’t know if it would actually work. The triggering technology was there to make these electronic drum instruments but I’ve never seen anybody do it with hand percussion and we didn’t know if it could work. I started putting together a sound set with specific rhythms in mind. Once I started putting it together and realized it was going to work I started calling people to do the music.

I had a death in my family — my younger brother — which was a real blow in my life. I’m constantly within my religious practice taking time during the day to talk to my ancestors and to have a working daily relationship with them. Something about the chorus construction of the song made me think of my brother. I wanted to explore that relationship that I had with him and my other ancestors on my daily basis. The first line of the song is, “Dime hermano, soy tu servidor” which in English would be, “Tell me, my brother, I’m your servant.”

Where does the title of your album, IIII+IIII, come from?

IIII+IIII itself is the first sign of Ifá. Ifá is a divination system that is binary. It’s based off of yes and no, 1 and 0. In Ifá you have eight of these “yes or no” possibilities — four on the right side and four on the left side. “Ogbe” is the first symbol. Ogbe — when you have line, line, line, line — means open roads, purest light, the beginnings. With all these possibilities, four and four, you get 256 combinations. The very first and the king of all the combinations is IIII+IIII. So when that sign comes out of divination, one of the things that it marks is golpe de estado [state overthrow]. It also talks about separation because they’re two parallel lines that never meet.

You mention this relationship with your ancestors in this song, and your music is almost always referencing the spiritual practices of Ochá and Ifá.

“House Of Love” was a good starting point to me because part of the reason I made a decision to explore Ochá and initiate in the beginning was the desire in the overall sense to actively take a step to trying to understand or act in the invisible world.

I grew up in a church, my folks were Mennonites. I went to church every Sunday until I was 18 and I left the house. Once I began to understand the rule of Christianity as a tool of the colonizer, I had a really hard time accessing the spiritual beauty that I think other people are able to gain out of that practice. I felt for me that Ochá and the Yoruba practice felt more natural to me and, for reasons of ancestry, that it pertains to me.

I moved to Puerto Rico in ‘99. I did feel like my brother’s spirit was with me the entire time protecting me. And there were instances, whether it was through dreams or even actual projections a couple times, he was reaching out to me. So I had a sense that he was here with me but I was unable to understand how to access that in an effective way.

In 2012, I went to my first consulta [consultation] with a babalawo that became my godfather in Ifá. I went, not in a moment of need — a lot of time people will come to us having to solve a particular problem and they would like to resolve in life and they’re coming for a consultation for that reason. I came to my first consultation with everything in my physical world very much in control. The idea was that I felt like there was something beyond that I had. I felt that maybe Ochá and Ifá were ways to begin to understand that. When I consulted Ifá for the first time in 2012 one of my first questions was about my brother.

ÌFÉ's Otura Mun

Mariangel Gonzales

ÌFÉ's Otura Mun

Mariangel Gonzales

“My folks were Mennonites. I went to church every Sunday until I was 18. Once I began to understand the rule of Christianity as a tool of the colonizer, I had a really hard time accessing the spiritual beauty that other people are able to gain out of that practice.”

How do you as an African American see yourself and African American culture within this practice and religion?

In San Juan I lived in a neighborhood called La Perla which is right on the ocean. On the ancestor days when my brother had passed away or later when my grandmother passed away I would always go to the ocean and leave flowers for them, but I didn’t realize that was what people do when they would leave offerings for [the deity] Yemaya. What I have to believe is ancestral memory and knowledge inside of your bloodline. There were things that I was doing that were already there but I needed the guidance of my padrino and my elders to kind of say, “Look, this is how you do it.”

My first experiences with the Yoruba practice in the Caribbean were beautiful. In 2000 I played a millennium party as a DJ with some folks that were rumberos. I was DJing and there was a Nigerian singer and dancer that was hired to play the party too. It was really cool to see the Puerto Ricans and the Nigerians singing songs in the Yoruba language together that they knew. The Nigerian was in shock. He’s looking at these Puerto Ricans and I remember him saying, “You guys sound like my great great grandfather, your accent is his accent.”

It was really powerful for me being an African American and seeing that. Just to see language preserved and being repeated in a way that is understood is really powerful. Everything that went through preserving that language, preserving those prayers, preserving that practice through the middle passage is amazing.

How do you feel about the sudden rise in interest in the religion? From my observations, it has become an somewhat of an industry in Havana and New York City. It’s kind of trendy now.

First of all I should start with saying, I’m a baby in this religion. I just started in 2012. Everything is brand new to me so I cannot speak on authority with what’s happening in Cuba, Puerto Rico, or New York.

I try not to think of the religious practice in terms of popularity or mainstream or any of that. One thing I did like about this practice initially is that there was not a proactive push to any public sector of the religious practice itself. In fact, a lot of people don’t like to talk about it at all, which I suppose am challenging to a certain extent with what it is that I’m doing.

I think maybe in Cuba one of the interesting things is that the religion has created an economy where there is no economy. That’s just an example, but on the religious end, there’s going to be a ceremony, someone is going to pay that money. Other people are going to go to work, animals will be sacrificed, people will have meat, and the world moves on.

Do you feel pushback from your community because you talk about it so openly?

There are people who are not going to like what I do. My preoccupation on a spiritual end is to be a good babalawo, and to be a good babalawo to me means that I need to be available to help people and to take the good will and the well-being for the person that I’m consulting for— take that well-being as the highest priority as a way that it reflects in my work. I have someone’s spiritual journey and destiny in my hands. I am advising them.

For me it’s about effectiveness. Going back to people on whether you can trust their intentions. My question is are they knowledgeable and are they going to do those coronations and those ceremonies correctly, and if they are, it does not matter what their intents are. For me, it’s about doing the things properly for the people that are coming to you.

The world as I know it is changing constantly, and that’s just a revealing process and an inspiring one. Those are the things that are making me push and search farther. They’re beautiful moments for me. I'm writing around those moments but I don’t feel that anything that I’m writing or speaking about to people are things that I was told in confidence. Some of the ceremonies are secret — I will never talk to anyone about what happened inside the room of Ifá because I swore not to talk about those things and I take those things very seriously. One thing that is different now is that the religion itself isn’t illegal anymore.

“It was really powerful for me being an African American and seeing Puerto Ricans and Nigerians singing songs in the Yoruba language together. Just to see language preserved and being repeated in a way that is understood is really powerful.”

You’ve been in Puerto Rico for seventeen years. What is your relationship with the island now?

After the past couple years I am coming up to a point where I spent more time in Puerto Rico than in Indiana where I was born and raised, so I arguably know Puerto Rico better than I know Indiana.

The Black experience in the U.S., to me, is being part of a group of oppressed people. And to have some other group tell you, “You can’t do this,” “You’re not good enough to do this,” “You don’t deserve to do that.” I’m aware of systematic racism and oppression. The problem in Puerto Rico is colonialism. The colonialism tells you you can’t drive your own life. So for me the most important thing on a fundamental level is the idea of decolonization. In one way or another I believe that my friends and neighbors and the people who have been there for me need to be free.

There’s a feeling here that I’ve run into a lot of times with musicians and other artists: that they can’t get out of Puerto Rico. Their voice and the things that they’re doing aren’t as relevant as the things that are happening in the United States. It’s this psychology, you can see it here — the Puerto Rican government runs 70 billion dollar debts and the feds send in some unappointed people to set up a neoliberal task force and the neoliberal task force has an 85% approval rate on the island. Something that is ridiculous — sending unelected people to run the government of Puerto Rico — sounds ludicrous, but what’s even crazier is that there’s an 85% approval rate.

It reflects an attitude of people saying, “We’re not smart enough to do this. We don’t deserve to run this country. They can do a better job.” That’s the sentiment, it’s sad. I really do feel like people think that people don’t have a voice and that’s been confirmed by the last two supreme court cases that have come down in the past year. They have said unequivocally, “You do not have a voice. The power is with the federal government. You have a constitution but it doesn’t matter. The constitution is subordinate to the U.S. federal constitution. You don’t make decisions. We make them.”

What do you envision for the future of Puerto Rico?

I don’t believe in the nation state, but there is such a thing as freedom.

I’m not so into fantasy in terms of music right now, because I’m dealing with the realness of the situation — the political situation — that both United States and Puerto Rico needs. We have to free ourselves from the United States. The colonial situation needs to end. Puerto Rico needs to be free and then from that position of freedom, then we can start working and figuring out what we’re going to do in this place.

This song “Bangah” is me exploring the idea of freedom. When I first heard the beat I knew it was a war song. I don’t believe in war as a way to solve problems, but let’s talk about war, let’s explore the idea of conflict. Who is the owner of war? The owner of war in the Yoruba pantheon is Ogún. I am imagining Ogún as the divine machetero, and I think about the idea of Ogún and his power to wage war and the power to focus and also work, the idea of working towards liberty and what liberty and freedom means on an individual level first. The idea of being able to focus and decide, I’m going to do something and I’ve made a decision to do that and I’m going to work towards that and you’re going to have to kill me for me to stop working towards that. I think that’s the kind of determination on an individual level that will allow us to be the people we need to be here on the island to free ourselves from the chokehold of colonization in all its forms.