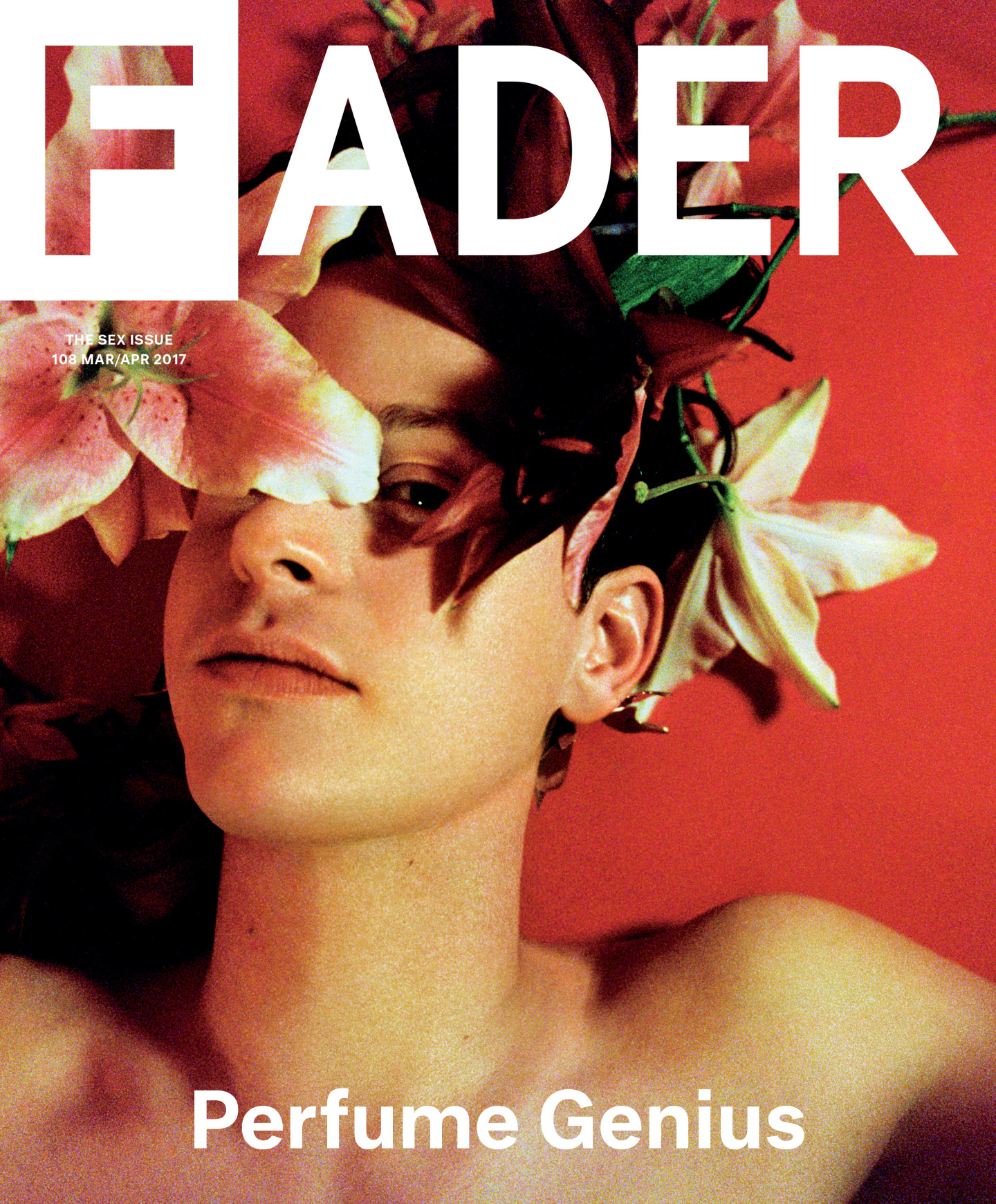

Photography by Cara Stricker

Fashion by Hillary Taymour

Grooming by Casey Gouveia

Earrings FARIS, shorts SPANX.

Earrings FARIS, shorts SPANX.

If anyone is keeping the tradition of gay kitsch alive for the 21st century, it’s Mike Hadreas. He and his boyfriend of eight years, Alan Wyffels, both 35, live on a corner in Tacoma, Washington, in a house painted lemon on the outside, lime on the inside. There are animal figurines everywhere, an unnerving vintage color illustration of a child above the toilet that stares at me when I pee, and a Wi-Fi account called “Edith.”

Mike, better known as Perfume Genius, has the slight build of someone 20 years younger, with a hook of a nose and a wave of hair that he sometimes slicks into a New Wave part. He has a heartland lilt to his voice. It splinters when he’s speaking about something serious and sharpens when he’s cracking a joke, which is often. Sometimes, he’ll interrupt a conversation to whisper dramatically in his dog’s ear that she’s “stunning.” He loves this pup, a chihuahua named Wanda who flits around in a pink collar by Martha Stewart Pets, her nails clicking loudly. She’s had digestion issues in the past, and Mike sometimes, happily, has to massage her tummy to help her go to the bathroom.

Though their house is chichi in spirit, Mike tells me he’s earnest about its interior design. “I like thinking that someone made that,” he says of his tchotchkes. In fact, though he has a biting sense of humor, he’s pretty heartfelt about everything in his life, particularly the sacred music he makes upstairs, in a small triangular crawl space on the second floor. Across his first three albums as Perfume Genius, which he started releasing in 2010, he has been worshipped for making songs that rely on battered melodies and painstakingly immediate poetry about depression and drug abuse. Both Mike and Alan have been sober for about eight years after a lifetime of struggling with various intoxicants. “Everything but heroin,” Mike says.

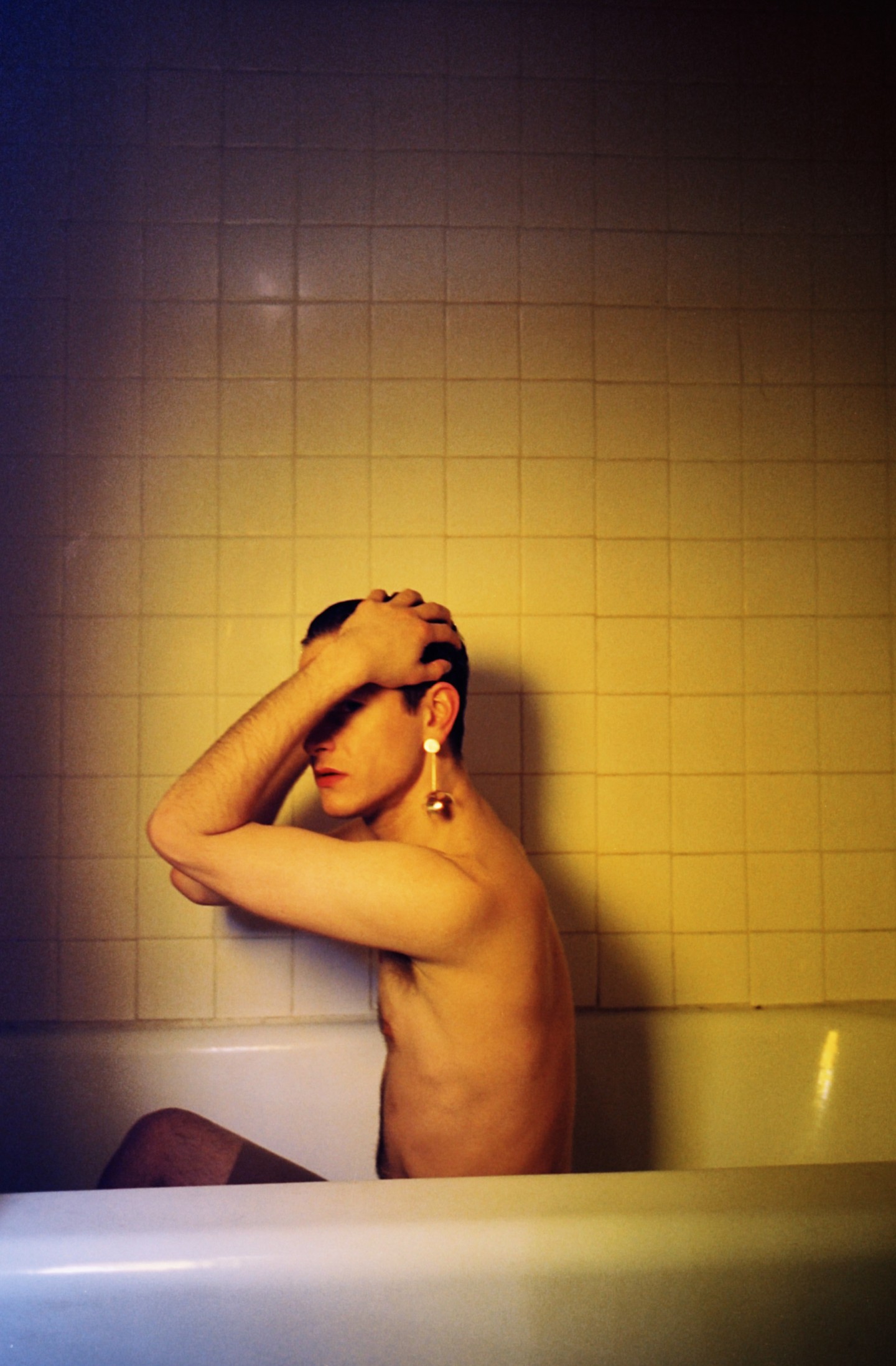

Earring FARIS.

Earring FARIS.

The honesty in Perfume Genius’s music has attracted him a devoted audience, and he receives a lot of messages on Twitter from young kids going through the process of coming out, or dealing with their own addictions. “I think people come to my music just to feel less lonely,” he says. “When I write, sometimes I think, What would I have liked to have heard when I was younger?” But on his new record, out this May, he aimed for something a little more developed: essentially, he wanted to make a grown-up album about life after you’ve trudged through the trauma.

The new record centers on the complex melodrama of small things, the strange anxieties that persist even when you’ve finally got your life, to some extent, together. Mike would come up to the house’s tiny attic, often with his puppy by his side — “She likes to hear me sing,” he says — to mess around on a synth and chant gibberish melodies that he’d eventually replace with lyrics. There are allusions to finding God and love and self-esteem, but it's also an album of mood swings, from flowing strings to sexy glam rock. Its triumphant choruses give way to fevered howls. This is how it is, the album seems to say, when things are not, and never have been, perfect. “I think it would’ve been too easy for him to just write sob stories about being a drug addict,” says Alan, who looks like a thrift store James Dean, handsome and burly with a dimple on his chin. “When you are a drug addict and alcoholic, you function in crisis mode all the time. Learning and Put Your Back N 2 It was Mike processing those things. Too Bright was a lot of anger. And this album is like, OK, we’re on the other side.”

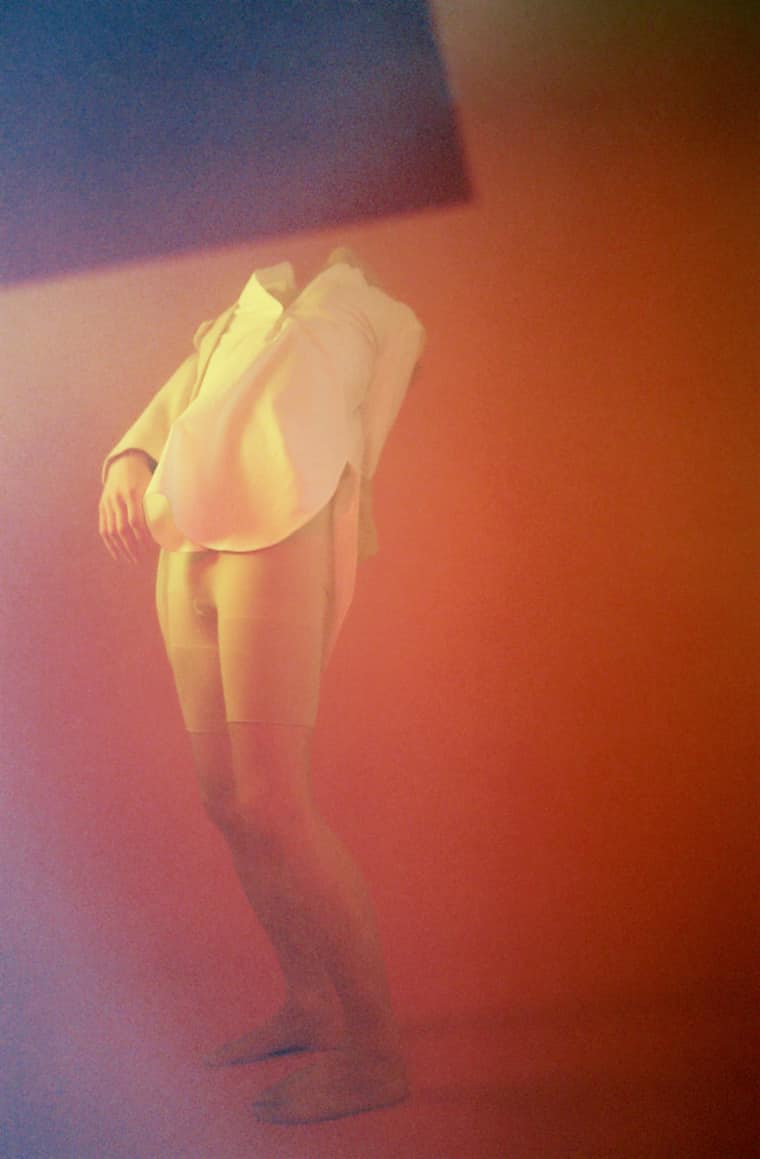

Tunic NEED, jacket STYLIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX.

Tunic NEED, jacket STYLIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX.

“I think people come to my music just to feel less lonely. When I write, sometimes I think, What would I have liked to have heard when I was younger?” — Perfume Genius

Growing up outside of Seattle, Mike was picked on relentlessly for being feminine. “By about 11 or 12, you have enough people telling you that’s not how you’re supposed to walk, how you’re supposed to talk,” he says. “Kids started becoming a little more mean and physical.” He got bullied in high school, too, but made it through by keeping journals and obsessively listening to songwriters like Liz Phair and PJ Harvey.

Thinking he’d be a painter, he enrolled at Cornish College of the Arts, in Seattle, where he stayed for a year before dropping out, hanging around the city for a while, then moving to New York at 21 to be with a boyfriend he met on Makeoutclub, a now-defunct online dating service. In New York, he worked at a bar and partied. “I had a lot of fun. It’s like how you think it’s going to be. It felt like I was an artist even though I was doing absolutely no art,” he says. “The partying became more about just doing the drugs and just getting completely fucking shitfaced. We stopped paying rent. It wasn’t working.” By the time he was 25, he had moved back home after running out of money, and, eventually, asked his mom for help. She drove him to rehab, where he stayed for 20 days. “I didn’t talk at all for the first four days. I was so terrified,” he says. “Then there’s something so freeing: there’s lots of group therapy, and you’re just around people all the time because you’re all locked together. By the end of it, I was facilitating the discussions.”

After rehab, the world seemed new. “I had so many emotions. It’s like when you quit smoking, you can smell again.” In 2005, he began to write the songs that would become his first album, Learning, which he recorded by himself in his mom’s home. “Mr. Peterson” is about a high school teacher who took advantage of him sexually and then later killed himself (Mike says this song is partly based on a true story, but declines to say which part): “He made me a tape of Joy Division/ He told me there was part of him missing / When I was 16/ He jumped off a building.” He posted much of the album on Myspace in 2008, and was spotted and signed by Matador soon after. By the time the album was released in 2010, he had relapsed. “I just got confused,” he says. “On the weekends I was going down to the city and partying.” That’s when he met Alan.

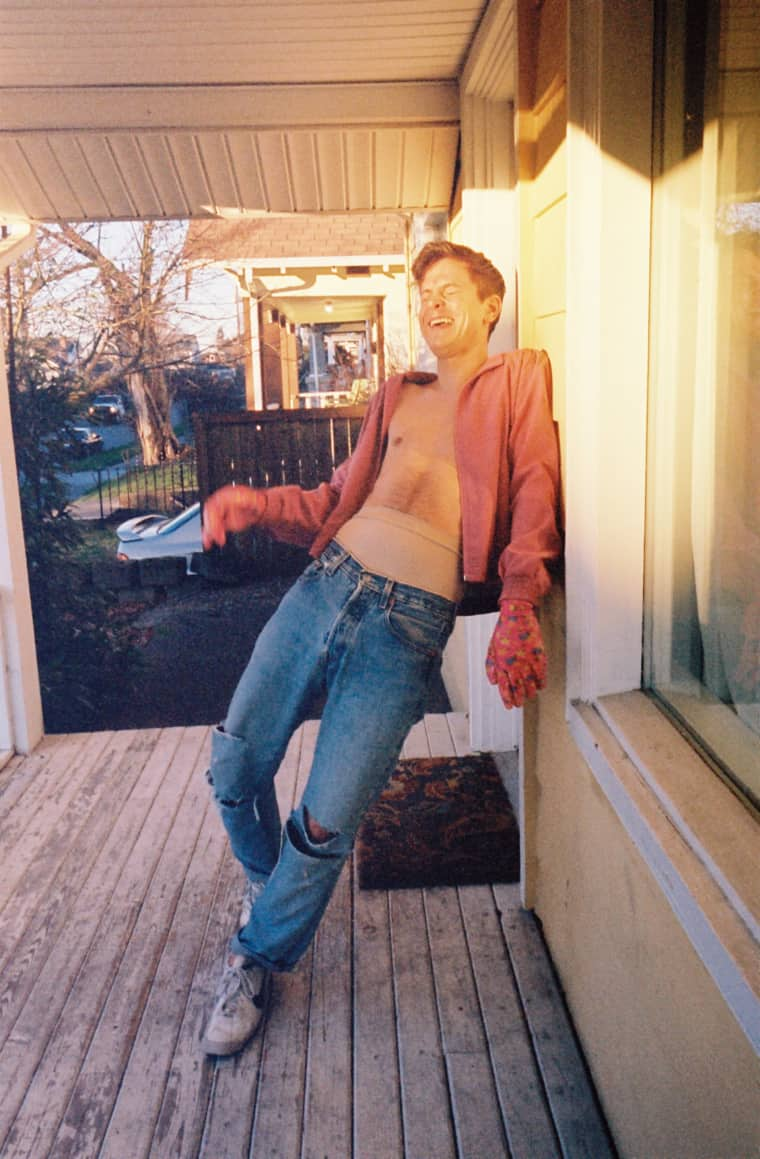

Mike: pants NEED, T-shirt WALES BONNER. Alan: jeans NUDIE JEANS, top WAC.

Mike: pants NEED, T-shirt WALES BONNER. Alan: jeans NUDIE JEANS, top WAC.

T-shirt and top COLLINA STRADA.

T-shirt and top COLLINA STRADA.

A mutual friend introduced them, hoping Alan could help Mike get sober again, and they quickly became close friends. “A lot of people just don’t want to sit down and process a bunch of shit. But we could with each other,” Mike says. “If I called him at 2 in the morning saying, ‘I need help,’ he would come.” “It sounds cheesy but I instantly knew he would change my life,” Alan tells me.

Alan took Mike to AA meetings, exposing him to a version of life that he hadn’t seen before. “I met a lot of older gay men who were really kindhearted and accepting and warm,” Mike says. “To just see these happy, contented, joyous gay men was a really powerful thing. They would be telling their stories about what was happening to them in their current sober life that were very hard. But they were fucking living their life anyway, and they were trying to be the best version of themselves.”

As Mike’s career began to take shape, Alan, a classically trained musician, helped him rig his first live shows and accompanied him on piano. One night, at a movie, Mike unexpectedly grabbed Alan’s hand in the dark. Afterwards, they kissed on the street. “It was like teenagers and we were near 30,” Mike says. Within a week, they were saying “I love you” and looking for an apartment to share in Seattle. “We had never had sex sober before, either of us,” says Mike. “It was just very weird to be very present. There were no edges smoothed — it’s just you and him. It’s very intimate. If you open your eyes, it’s weird, because there you are.”

His new LP, which does not yet have a name, is an album about living on the other side of, but never fully escaping, both torment and fury. In that respect, it might be seen as a kind of queer companion to Solange’s 2016 album A Seat at the Table, a tense hymnal about the banal, inescapable racism of everyday life, and the anguishes of life as a black woman at this particular time. On their respective albums, both artists elucidate the steps that they have taken to find a little peace — like committing to a partner who loves them and settling in a city (in Solange’s case, New Orleans) outside of the media glare of L.A. or New York. On his album, Mike works to process the anxiety of gay life in this strange moment, in which gay marriage has become legal across the country (he and Alan have discussed marriage but are unsure of whether or not it’s for them), but a newly elected Vice President believes people can be electroshocked into heterosexuality and seeks to backpedal advances in LGBTQ rights. “A long time ago, I felt like there was something wrong with me [for being gay]. And there never was,” Mike says. “But there’s just, like, people who will kill you on the street.”

Turtleneck ARTIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX, necklace FARIS.

Turtleneck ARTIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX, necklace FARIS.

“Some people think, I’m going to quit drinking and all my problems will be solved. But when you quit drinking, all your problems are actually pretty glaring. You have to stop, you have to repair your relationships, you have to think about your health, and paying bills, and being an adult.” — Alan Wyffels

There doesn’t seem to be a ton to see in Tacoma, aside from a museum of contemporary glass art, a couple of gay bars, and a spattering of strip malls. On a drive through Point Defiance, a park along the coast from which you can see barges sailing by and Mount Rainier looming hard and white like a ’50s movie backdrop, Alan points out the so-called Tacoma Aroma, a sulfurous stench that lingers in the city, attributed to a variety of sources, including a nearby paper mill, a rendering plant, and an oil refinery. “The smell can be strangely comforting,” says Alan.

Mike has been trying to take care of himself by hunting down healthy Ayurvedic vitamins and tinctures, and one evening, we head to a brightly lit organic market to pick up herbs like boswellia and ashwagandha. He glides through the aisles on the back of a cart, unable to explain exactly what these medicines do for his wellbeing; he just seems to like saying the names out loud. He worries, over the course of our time together, about a breakout of acne, so the next day, after a lunch of burgers and chicken teriyaki sandwiches at Red Robin, we go to a mall Sephora to find tinted moisturizer. A woman who works there says the right shade for him is “Porcelain,” then sells him on a lip balm, too.

Mostly though, Mike seems to prefer hanging around his home. He ambles around in a comfy oversized turtleneck, no manicure or visible makeup, and holds court on the couch under as many blankets as he can find. He has a stock of Diet Coke in the fridge (he says he drinks six cans a day, but I swear I see him drink more) and likes to watch reality TV competitions, like Survivor and The Great British Bake Off. He quit smoking cigarettes two years ago, but keeps a vape close by. He updates his famously hilarious Twitter account; he suspects that some of its more than 200,000 followers think he’s an internet comedian and don’t know that he’s a musician. He says humor comes from the same place as sadness for him — just two different ways of looking at the truth. “If I curated a festival it would be an 8 hour long buffet and then Bonnie Raitt rides in on a motorcycle with dessert in the sidecar,” goes one tweet.

The couple has settled into a nice rhythm. In the morning, Alan will wake up for his job teaching piano and give Mike a massage to ease pain in his joints caused by Crohn’s Disease, a chronic disorder that Mike has suffered from since he was a kid. “It’s not a cute disease. I’m essentially just bleeding. I have lots of open wounds in my intestines. It’s just your body betraying you,” he says. “I really do not like it.” They have worked on making life around the house as comfortable as possible, and Mike says his most profound obsession is coziness; the couple’s biggest splurge has been a Tempurpedic mattress, which they are paying off in installments. Mike works on music while Alan is at work, and then often cooks up a hearty “Honey, I’m home!” meal for dinner. On one night of my visit, he serves a perfectly tangy orange fish curry. Afterwards, Alan does the dishes.

Mike and Alan both tell me repeatedly that they take care of each other in equal measure, but Alan does seem to offer up a certain dependability. Mike can’t drive, and so Alan zips them around. His more formal music training has been integral to Perfume Genius’s career, too. “I’m honest,” Alan says. “I will tell him, ‘I think this sucks.’” When I ask Alan if it’s tough to always be a supporting player, he is genuinely starry-eyed about just being on the team. “I’m grateful to be a part of it,” he says. He also seems like Mike’s proudest fan. “He wants to be the musician he would’ve [needed] as a teenager,” he says. “And I think he’s doing that. He’s singing about things that no other gay male singer is singing about. About his pain, about his experiences.”

Tunic NEED, jacket STYLIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX.

Tunic NEED, jacket STYLIST'S OWN, shorts SPANX.

Much of the new album was made in Los Angeles studios. Intent on wrapping his lines around a larger musical picture, Mike focused on writing melodies before lyrics. Producer Blake Mills, a past collaborator with Fiona Apple and John Legend, was recruited to help make things sound big. “My biggest hope on the record was that Mike’s voice was going to be presented in a way that is larger than anything he’s done,” Mills says. The team played around with studio magic, using a dummy with two microphones inside the ears to capture sound the way the human head does, sending sound Boy Scout-style through two tin cans separated by a string, and positioning vocalists in a choir setup to give their words a churchy aura.

Whereas Perfume Genius’s music has mostly been characterized by how stripped down and immediate it is, this time Mike tried to foreground textures that he couldn’t just create with his voice and three chords. “I didn’t want everything to be based just around the piano,” he says. “When it was just me and a few elements, I knew I was in full control. I could wing it. This time I tried to push myself to not go to the chord I naturally would have. I wanted to be like, ‘I’m a musician!’ To go for it.”

Still, there’s plenty of angst lurking beneath that pumped-up sound. On one afternoon, Mike is hyped up on Diet Coke and Wanda is looking sheepish after puking on one of the sofa cushions as we discuss “Die 4 You,” a new song that unfurls like the quiet storm of Sade. Mike tells me it is actually about erotic asphyxiation, the sometimes fatal fetish in which people restrict the flow of oxygen to their brain to achieve sexual arousal. “It’s a metaphor for giving all of yourself to someone else,” he says. “You can push it so far that I might even die and that would be OK.” It’s a surprising metaphor for the intense closeness he feels with Alan, and he’s not so clear about why disquieting thoughts persist on this album, even when his relationship is so seemingly open-faced. “I thought it was braver to make something that tries to approach happiness. But even though the songs might sound upbeat, the lyrics are like, 'The only peace I will find is if I die,'” he says.

Mike seems to have it all — the house, the man, the career, the dog — but, throughout our time together, he tells me repeatedly that he is still haunted by ghosts, literally: the fragile “Every Night” is about an ominous spectral presence he senses wandering the house. “I have no reason to be as melancholy as I am,” he says, trailing off with a little sigh. “When l objectively look at it, I’m contented. I’m just sick of it…” Sick of what? I ask. “I don’t know, man. I’m trying to figure it out. I think a lot of it is this feeling that there’s something wrong with me — that I’m a bad person, that I’m not right. You know, I don’t feel like I make sense in the world. I don’t feel like I look right, I don’t feel like I act right or do right. It’s very frustrating to me that I just walk around with this all the time. I’ve made shit-loads of progress, but I want all of it to go. I’m not happy with it just being better. I want to be a ball of light just floating around.”

“Sobriety doesn’t solve everything,” Alan tells me. “Recovery is hard, and it’s really uncomfortable all the time. Some people think, I’m going to quit drinking and all my problems will be solved. But when you quit drinking, all your problems are actually pretty glaring. You have to stop, you have to repair your relationships, you have to think about your health, and paying bills, and being an adult.”

Tunic NEED.

Tunic NEED.

Turtleneck MIKE'S OWN, shorts SPANKX, necklace FARIS.

Turtleneck MIKE'S OWN, shorts SPANKX, necklace FARIS.

“I’m here, how weird.” — Perfume Genius

Most of all, the new album is born from the boring challenges involved with just showing up to your life every day. Being there for another person and for yourself, staying sober, paying off your mattress, cleaning up the dog’s throw-up, or cooking dinner. When you’ve spent a big chunk of your days not believing you deserve a normal life, it’s strange to wake up one day, look around at your sweet little home, and realize that you made it happen anyway. “I’ve been making good decisions and taking care of myself for a pretty decent amount of time,” Mike says. “I haven’t fucked it up. I haven’t left. I haven’t gone back to the way I used to be.”

On the heart-wrenching “Alan,” Mike sings about the comfort of his life with his boyfriend, and also the discomfort of that comfort: “Did you notice we sleep through the night/ Did you notice, babe, everything’s alright/ You need me, rest easy/ I’m here, how weird,” stretching his voice on “weird” so that it becomes the focal point. “It’s almost embarrassing to acknowledge how good things are,” Mike says. “There’s something abnormal about it.”

This is what makes Perfume Genius’s new music such a radical departure from the kind of portrayals of LGBTQ life that we’re used to hearing about in, say, the violent youth-obsessed novels of Dennis Cooper or the doomed nihilistic teenage films of Gregg Araki. Even Brokeback Mountain, the canonical gay film, ends with two men who can never admit that they should be together, with one character dying alone on the prairie and the other mourning him forever. But it’s easy to perish in art, and much harder to persist in life, as Mike has. It might not be as dramatic to survive, but it also means you get to not die. Mike has already processed a lot of trauma in his work, and though he wrote most of the album before the most recent presidential election, its timing couldn’t be better: here is a way to endure, less operatic than the chaos of youth but no less fertile.

And, free from more dire problems, Mike has been able to focus on the more immediate task of making music, and even mature to a place where he feels playful and excited to experiment. Maybe it’s better not to burn out or fade away but to stick around and see what happens. “I started writing songs later in life because I just couldn’t commit to it before,” he says. “I guess it just matters enough to me now. You’re obsessed with the feeling of making an actual thing. That’s where all the purpose comes from, even if it’s hard. It’s the only thing I have that gives me that feeling.”

And so, one day during a trip to an ice rink in the southern part of Tacoma, I’m a little surprised to hear that Mike and Alan have plans to leave suburban Washington some time next year to move to Los Angeles. Country music is playing from the speakers above, Alan is braving a backwards glide, and Mike is having fun hanging by the wall, posing for a picture that will eventually go on Instagram. He tires quickly, and says the skates we rented hurt his shins. As parents and their children waltz by, we retreat to a common area with instant coffee makers and vending machines. Though they worry they won’t be able to afford a home quite as roomy in Los Angeles, he tells me they get bored and lonely in such a small town, and the quality of the food is much better in L.A. “I think living here feels like hiding sometimes,” he’ll tell me later.

It had seemed that they had figured out something essential here in Tacoma, tucked away from the rest of the world, but it turns out quaint domesticity isn’t their whole story either: people are multifaceted, and Mike and Alan, with Wanda the chihuahua in tow, are ready to take a new step. Yearning is eternal, it turns out, no matter how cute your home.

Earrings FARIS, shorts SPANX.

Earrings FARIS, shorts SPANX.