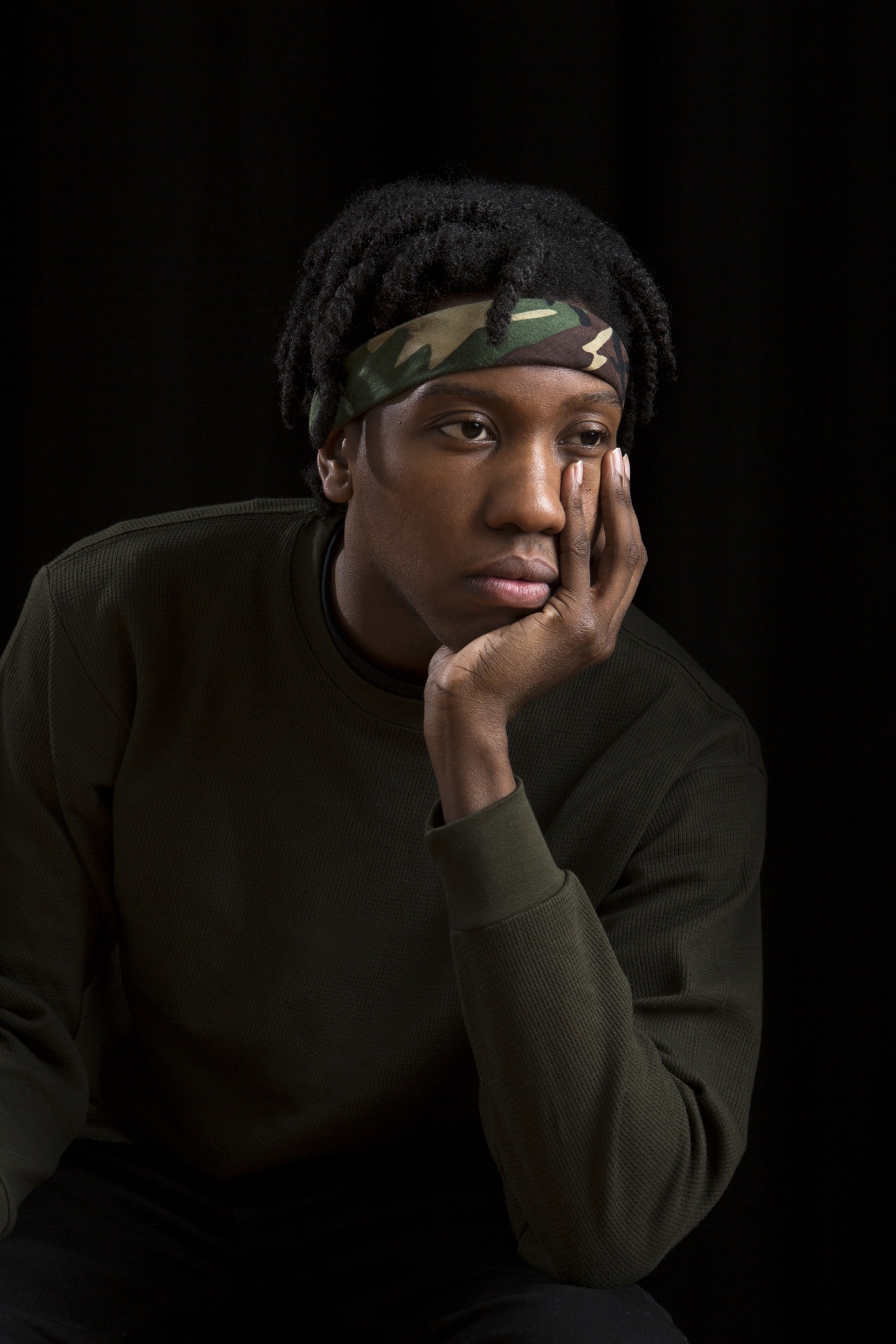

Robert Adam Mayer

Robert Adam Mayer

At 26 years old, Kemba has already endured a lifetime’s worth of painful let downs and loss. “Yesterday, my mom passed,” he said when we spoke over the phone earlier this week. In December, he told me, he also lost his aunt. “I’m not depressed about these things happening. I’m just sad that family members are leaving and that I won’t be able to speak to them anymore. Especially my mother. I believe they’re here and their energy is being transferred to someone else. She’s watching and guiding me.”

Amid it all, the Bronx-bred rapper has remained ever hopeful. “Blessings usually spring forth from these types of things.” Formerly known as YC The Cynic, Kemba has been rapping since 2013. But it wasn’t until last June that his work took on new meaning, with the release of his Negus album. Just a few months after that, in December, he reached a critical mass when he dropped an arrestingly baroque freestyle on HOT 97’s Real Late with Peter Rosenberg — it was a short-lived viral hit. “We always find a way/ we don’t wait for no damn petition to handle it,” he rapped, a mix of heart and exclamation. A week later at a show, a group of friends had to nearly push him to go on stage with Compton prodigy Kendrick Lamar, who was pulling people out of the crowd to rap. Kemba’s was a standout performance: nimble, socially relevant, and all feeling. “He was kicking some real mortherfucking shit,” Lamar was forced to admit.

Today, Kemba arrives with the premiere of “Already,” his first video release since that eventful night. The Bronx native talked to The FADER about dealing with tragedies, his love for black people, and how a trip to Ferguson inspired his last album.

Resilience seems to be a really big theme in your personal life and especially in this last album you put out. Can you talk about it being the common thread between your work?

Well first, I just think black people are incredible. In my own life, I’ve gone through some very crazy shit. One time I was on my way to a concert and I got jumped — fucked up. I went to the hospital and they were like, “Did you get into a car crash? Are you sure this was regular people?” I literally got surgery the same day and then left for South by Southwest two days after that to perform. It was the craziest thing, right out of a movie. My face was still swollen, I could taste blood in my mouth, I couldn’t rap super fast, and I felt the limitations. I really feel like hardship breeds creativity, and after so many years of hardships, that’s what I have.

You’ve gained momentum these past few months. Tell me about the viral freestyle you did on Peter Rosenberg’s show in December. How did that come about?

I met Rosenberg years ago, because of Homeboy Sandman; he’s an underground rapper from New York City. He introduced Rosenberg to my music and since then, we've kind of been keeping up with each other ever since. I asked him to DJ at a late release/birthday party in November ,and that’s when we kind of connected more. From there, he invited me to do the show. I wrote that freestyle for that interview. When I woke up I was reciting it, I went to record it, I listened to it; when I went to sleep, I was playing it in my sleep for a week straight. But when I got to the studio, I said the first line and forgot all of it — forgot the whole entire thing. We had to a couple takes but he was super gracious about that. When it came out, the freestyle kind of started taking off on its own. WorldStar posted it on their Facebook page and a lot of people started sharing it, then the Kendrick thing happened the next week.

So how did that whole thing happen with Kendrick? Did you know when you went to the show that you were going to rap on stage?

Not at all! My friend Nakisha called me at 7 p.m. and was like, “You gotta get to Brooklyn by 8. I got this Kendrick show and I can get you in!" I got out of my bed, brushed my teeth, and got there. I guess, just by luck, a bunch of people closer to me were people I knew, like Scottie Beam who I had just met at HOT 97. She stood next to me and then my boy Potential who works for TDE was next to me. So when they started calling people up, they were the ones trying to make that happen. I’m always adamantly not trying to rap. [Laughs]

Why is that?

Music is super personal to me. I like writing and creating a whole experience. I love performing on my own. I love recording music on my own. When that’s taken out of its element and kind of isolated, like when I have to do a freestyle over a different beat or if I have to be in a cypher, or any kind of spontaneous thing, I don’t really love doing that. But I love making these whole entire worlds. After he called up the first person, Scottie was like, “You should be up there!” She wasn’t taking no for an answer. Then my friend Nakisha started screaming. By the second person, he called up somebody else. After that, everybody was screaming. He couldn’t not notice that a whole section was pointing at me and screaming.

When you first started recording in 2013 you were going by YC The Cynic. Why did you start going by Kemba?

I put out my last project as YC The Cynic in 2013 called GNK and right after that I started feeling like the name wasn’t fitting me anymore. I got the name YC when I was like 12 years old. I came up in a time where the internet was around but everybody didn’t always have access to it, so you were still going by old rules. Like, I had to go through open mics and I wasn’t uploading music on YouTube immediately. When I got my name, I got my name from the people in my neighborhood. They didn’t know me. So, as I got older, it was kind of fitting me less and less if that makes any sense. I started brainstorming different names and I didn’t wanna take anything that already had a meaning, like The Cynic did. I just wanted to find something that felt good to me, that sounded good to me, and kind of felt like characteristics that I want to embody. Kemba sounded young and powerful. I didn’t want it to have an innate meaning because I wanted to make any kind of music that I felt like.

You took a trip to Ferguson that inspired Negus. Tell me about that.

I was in a community group called Rebel Arts Collective and they were teaching me about the Black Panthers and all the other kind of movements. The Black Power Movement, it always looked like movements that were now run by older folks. In the movies they were run by kids or young people, but in actuality they were all older folks. When I went to Ferguson, all the marches were led by people that looked like me, and people who were bumping Lil Boosie or things that I could relate to. Things that really made me feel like I could be a leader. I don't think I’m a leader, but it made me feel like that could be me. It made me feel more powerful. I was super inspired by that.

It took you three years to write the album. Was it difficult for you to encapsulate all of those feelings and all of the angst? What took you that amount of time and what was the process like?

It was pretty difficult. The album before was heavy in its own right. When I finished that, I wanted to do something light-hearted, I wanted to do something more melodic and brighter in sounds, and it just wasn’t happening. I wasn’t making anything that I felt was good. That took a lot of time just trying to force something. Then I had life issues and three surgeries. After the Ferguson trip, I think it started to flow really smoothly. I just had to figure out what kind of narrative the album was going to have, how to make it sound, how to balance my feelings with trying to write a good song. When you put out an album you get all this feedback and you hate it, but you kind of still listen to it. I kept hearing that on the album before — that it was too heavy, that it wasn’t marketable. I was trying to fit in and it just wasn’t working.

Do you think timeliness of your music has something to do with the how it’s been resonating now, despite Negus being sort of heavy too?

I think that people are coming around to the idea that you can make music about what’s going on. For the longest time it was like, “Oh, what are you rapping about? Get that away from me!” before even listening to it. Now with people like Beyonce or Kendrick, people are more willing to listen. Once you get past that barrier, it’s about whether the music is good or not. I don’t blame the listeners, but it’s dope that now we can talk about anything and if it’s good it will shine through.