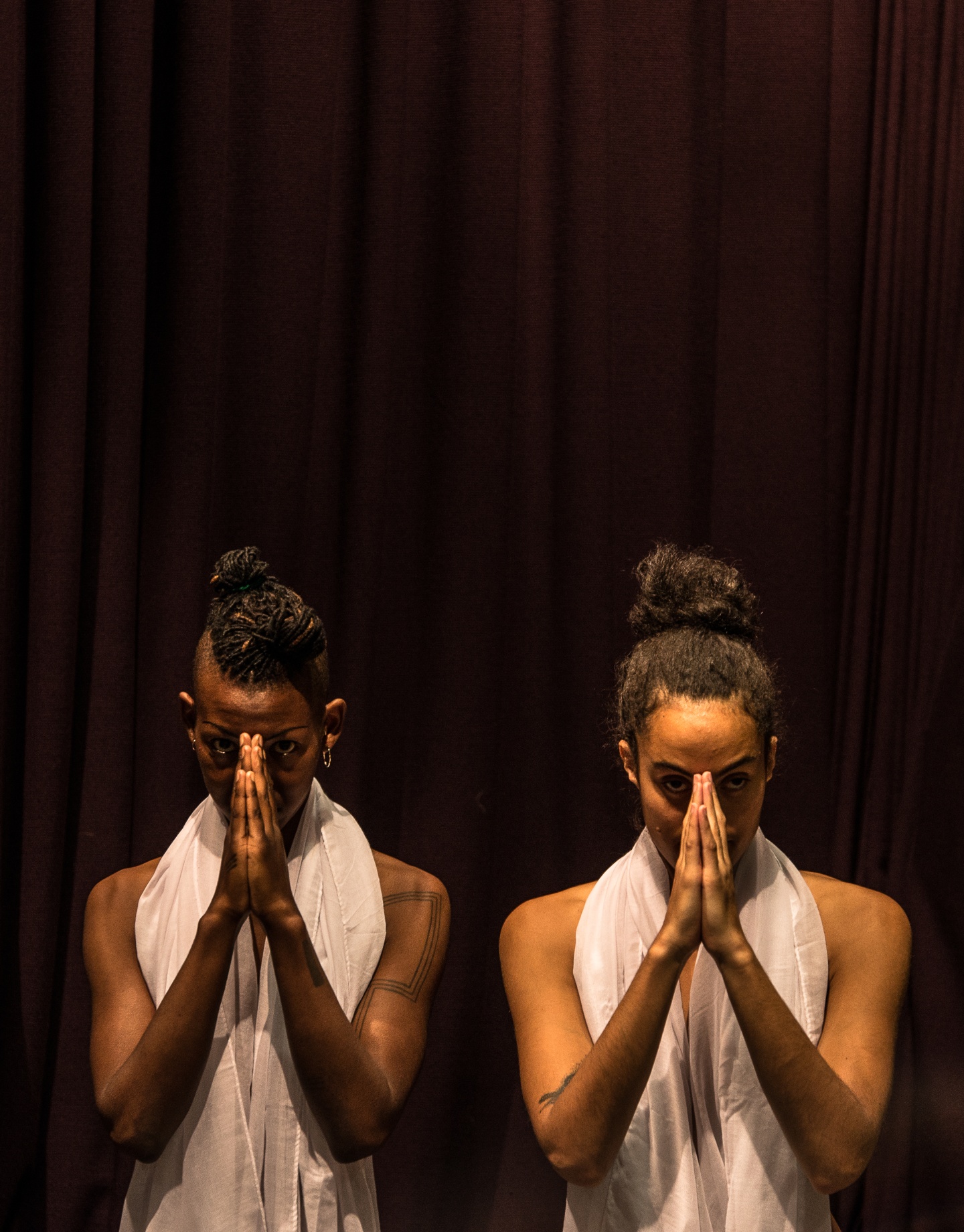

Project O Is The Duo Taking “A Big Puke On The White Dance World”

These London dancers confront the fetishization of black and mixed women’s bodies in their powerful performances.

Katarzyna Perlak

Katarzyna Perlak

“I was told that black people don’t have the same arches as white people, we have a bum, told my legs were too long, asked how I supported my big thighs,” said Alexandrina Hemsley matter-of-factly. The London-based dancer was reflecting on her classical dance training, speaking at a café in London art center Somerset House on a cold January evening. “There was always an awareness of my difference.”

As one half of radical dance duo Project O, Hemsley, and her dance partner, Jamila Johnson Small, takes this feeling of difference and wields it like a weapon. Since forming in 2010, they have taken over spaces ranging from prestigious theaters to a men’s public washroom with their improvisation-led performances, subverting traditionally white venues through their very existence within them as black mixed-race women. Their dances, like O and Be Your Black Girlfriend, fluidly draw from the precision of ballet as well as the radical styles of the ‘70s and ‘80s, winding through issues of race, body politics, and female identity, with raw and mesmerizing effect. Though many black women have historically felt ostracized from the western classical dance world, in recent years we’ve seen dancers like Misty Copeland and Lemonade's Michaela DePrince pushing forward the black-led professional dance movement. Project O sits at the periphery of a change.

When we meet, the pair have just received confirmation of their latest bulk of funding for their current project, Voodoo. Even so, as their fingers twirl around celebratory glasses of burgundy red wine, they don’t seem to be totally relaxed. Each sits with a brown sketchbook which they intermittently use to jot down thoughts for the project in scratchy handwriting. In conversation they are both disarming and highly intelligent — the the type of people you want to tell your life to because you know they’ll take it seriously. Read on for our chat, in which they spoke about their complicated relationship with dance tradition, pushing against limits, and why representation is so crucial.

Did you start dancing when you were very young?

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: I grew up in London, then Kenya for four years and then I was in Thailand for a bit, and then back to London. I think I’ve always danced informally, from when I was young. There was always music in the house and there was always dancing. It was the possibility, wasn’t it?

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: Yeah. My mum would just dance, or I would dance with my auntie to Tina Turner videos. Things could bubble up, or bubble over into dancing. I’ve not been in a home of a white family and seen [dance] as a thing that just happens. I often think of the suppression of dance in this context — even though there’s the white canon with western concert dance and theater dancing.

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: When I was 11, I went to a boarding school in the southern Hampshire countryside. [I was] one of the only black people who was being super expressive with what they were wearing and having dreads. I had pencil cases tipped on my head to see how many erasers or pens would stay. I remember [in one lesson] the science teacher was like, “Oh, let’s see Alex’s hair because it’ll burn differently.” He cut off some hair and put it into the bunsen burner and it did a thing that was apparently different from other people’s hair. Mine was the different one. I didn’t really realize what was happening until afterwards.

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: Growing up, I didn’t relate to the images of black women I saw. Back then, if you didn’t listen to R&B you were the devil. That’s maybe why I found myself in such a white space [with dance]. How I’ve come to understand myself has very much been through the white alternative, avant-garde, left wing. The white other. That’s where I found solace, to an extent. And then I realized there was no solace for me there because I was alone.

Katarzyna Perlak

Katarzyna Perlak

“There is something strengthening in how we come together as two people, where we diverge and where we overlap.” —Alexandrina Hemsley

How did you first bond with each other?

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: We met at the London Contemporary Dance School on our postgrad. It was a really intense environment. Within that context your bodies are public property, in a way. People are constantly commenting on them, prodding, trying to adjust them to do a certain thing. I wasn’t thinking about being one of two minorities — I was focused on trying to get on the West End stage — but there was definitely an awareness of my difference. Then, when we started our MA, the dance schools were trying to do a push for getting more black people in. The environment kind of shifted as they tried to make space. That brought recognition of the times my body served those institutions.

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: I do remember being in a queue and we struck up a conversation about Tracy Chapman. And I remember a moment of being like, Ah, there’s someone here that I’ve not really spoken to before. Our meeting felt special because I’d met someone who had something to say about the white spaces we inhabit.

Jamila was supposed going on a residency in Ireland with another one of her collaborators, and she invited me along. It meant we could spend five days working on stuff together. At the time we were using Nina Simone's “Strange Fruit” to dance to, and we were told by a white guy that we couldn't, so it was an interesting start. After that we were like, Let's keep working on it. We looked from residencies and performances from there.

Could you succinctly describe the dancing within Project O?

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: Not really! It’s been evolving over the years. What remains the same is an interest in investigating the movement that comes from each of our bodies in particular, being confident with this, and pushing it too. The dancing is never exactly the same from show to show: we improvise, not setting steps but dancing in relation to all the other times we will have rehearsed or performed the choreography.

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: We continually revisit or “refresh” the choreography. It feels like a permission to delve into many selves and finding ways of meeting the particular moment of dancing. There is something strengthening in how we come together as two people, where we diverge and where we overlap.

What was your experience of ballet training like?

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: At the time, I found it really difficult. I found it really triggering, I guess? I was standing in front of mirrors, not being right, and being told I wasn’t right all the time. I felt fucking weird and not right somehow in the space. It exaggerated a sense of blackness. I don’t think I would ever dismiss ballet’s technique for what it can give a body, but I would just approach it very cautiously because of the the value placed upon it.

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: I think ballet is damaging. No one’s body does those things. That stuff is mad crazy shit that you need to do magic to attain. And you really do compromise things in order to achieve that aesthetic. But, after the last ballet classes I did, I didn't feel as if it was oppressing me – I had control of it.

Katarzyna Perlak

Katarzyna Perlak

One of the reasons why I stopped dancing as a kid was because I wasn't reflected in the petite white ballerinas I saw on stage. Do you hope that Project O could have inspired someone like me?

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: It comes down to representation, doesn’t it? With a stranger watching me all that I can hope for is that it means something to them. Because I don’t know them. So maybe they might feel a glimmer of familiarity.

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: I’m super happy and super moved if another brown person has been feeling alienated and loses a bit of that. That’s the best, best thing. But I’m not seeking that.

Who do you want Project O to be consumed by?

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: We’re trying to figure it out. Our last project, Naked Instincts, is going to be turned into seven short works made with specific spaces in mind. It’s our response to [receiving] invitations to perform in different contexts. With those works we’ve been considering who will be there in a different way to usual. But I think with O, our first show, it was just a big puke on the white dance world.

Can you share any details of what your forthcoming performance Voodoo is going to be like?

ALEXANDRINA HEMSLEY: I think Voodoo definitely marks a point of letting things in. With our fantasies, somehow commenting on the narrowing oppressions of racism by asserting ourselves as boundless…What if we could hold all the brown people of time past, present, and future within us, or channel [them] through us? It’s a process of looking at the assumptions placed on the brown female body and letting them all become you.

JAMILA JOHNSON SMALL: We are no longer afraid of being confrontational and we will fuck you up.