Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

These days, the conceptual artist Awol Erizku always starts his studio visits with a DJ set. Recently, in his downtown Los Angeles workspace, he stopped showing me the beginning stages of his abstract nail art paintings — featured in I Was Going To Call It Your Name But You Didn’t Let Me, a solo exhibition that debuted in early December during Art Basel Miami — and strolled over to his mixers. He intercut, what the musician and occasional art critic Greg Tate termed, “trap-beat rap” with drops from his friends: “You ain’t from the block. What the fuck you know about cuuulture?” enthused Uzi, his sometimes Bronx-bred studio hand, sounding like a characteristic Cardi B Instragram PSA.

In an emerging career once preoccupied primarily with photography, Erizku has since repositioned his focus to blending art with music. “Mixing is like art to me,” he said, standing before printed images he shot in 2013 of nude Ethiopian sex workers cast to look like black Venuses. “The sound has to follow the concept behind the work on display. There has to be a direct relationship between the sound and the visual.”

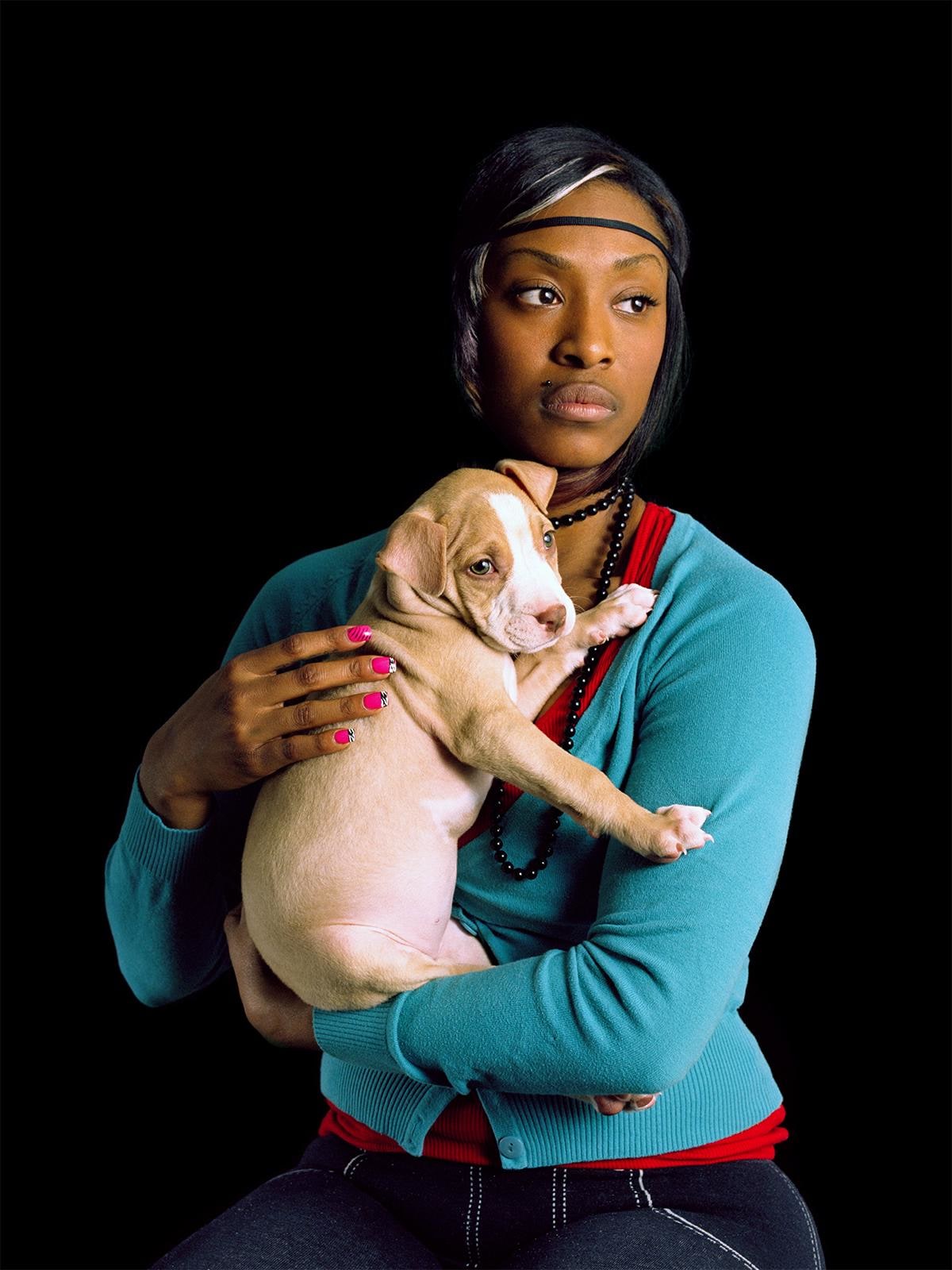

The 28-year-old artist was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and raised in the Andrew Jackson Houses in the South Bronx, but his influences were clear from an early age. In art school at Cooper Union and later at Yale School of Art, where he received his MFA in photography, Erizku was heavily impacted by rappers like Nas and Rakim, as well as the artists David Hammons and Marcel DuChamp. Trying to distill notions of black beauty and “update” key canonical and contemporary works in Western art, Erizku’s first set of photography replaced renaissance figures with fresh-faced black subjects (imagine Kehinde Wiley with a camera). In one such photograph, he repurposes Leonardo Da Vinci’s 15th Century portrait, Lady with an Ermine, as a twentysomething B-girl with faint highlights. The expressionless figure’s pink, blue, and white striped French manicure rests gently on the back of a baby pitbull she cradles in her arms. It is one portrait in a world of imagery that seeks, according to the artist, to “bring my generation into the conversation surrounding ideals of beauty.”

“Brukawit,” 2013.

“Brukawit,” 2013.

“Girl with Pitbull,” 2009.

“Girl with Pitbull,” 2009.

In the last few years, Erizku has moved away from that effort to focus on creating a vocabulary which pairs music with photography, sculpture, video, and painting that is rooted primarily in the rich material culture of everyday black aesthetic codes, a style popularized and given weight in the 1970s during the Black Arts Movement. As a result, he’s taken on work for Vogue, The New Yorker, and continues to collaborate with A$AP Rocky.

On a balmy December morning, standing in front of the finished nail art paintings at the Nina Johnson Gallery, Erizku shared the everyday motivations that drove his latest body of work. A number of the large-scale canvases were mounted on blood-red walls. “The hand is this ubiquitous symbol I saw growing up,” he said, dressed in all black and sporting a t-shirt that read “Esoteric” across the chest (an item from his merch line). “In the Bronx, all you see is liquor shops, barber shops, and nail salons.” For Erizku, French tips, crystal stamps, and long acrylic nails form a part of how many black people picture themselves. It’s a statement they want the world to see physically and know subtly: that black is beautiful.

With every exhibition, the artist has released what he calls a “conceptual mixtape,” which features songs that soundtrack his newest compositions. “For me the mixtape is like a hypothesis and the show is the proof,” he explained. The mix he created for the Nina Johnson show was more laid back than 2012’s hard-to-forget collaboration with DJ Kitty Cash for his Only Way Is Up solo exhibition in New York. (At Erizku’s direction, Cash mixed painter Kerry James Marshall’s 2012 lecture about beauty in the museum with a chopped-and-pitched version of Beyoncé’s “Drunk In Love.”) It was followed by mixes for his film Serendipity, a collaboration with MeLo-X that debuted at MoMA in 2015, and for his solo shows, New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus and Bad II the Bone, that Erizku created himself.

“Same Ol' Mistakes” - Rihanna, 2016.

“Same Ol' Mistakes” - Rihanna, 2016.

“Mixing is like art to me. The sound has to follow the concept behind the work on display.”

“Codeine Crazy” - Future, 2016.

“Codeine Crazy” - Future, 2016.

The mixtape for I Was Going To Call It Your Name But You Didn’t Let Me begins with an Uzi intro — “It’s Due Champ aka Flex Luger aka Awoool” — then moves smoothly into the harmony of Drake’s “Fire & Desire.” After, Uzi’s voice returns to offer a youthful testimony about the ecstasies of love. “Aight so, I used to date this girl but it wasn’t really dating,” she eulogizes over the syncopated beat. “We met and she wanted me OD but I ain’t know how I felt. I was like 18 and shorty was like 26. She was a dancer and shit. She was wiiiild. Like, if some shit was poppin’ off she would be, like, the first one, like, to be throwing the ones. She was fucking crazy,” Uzi offers, “but I fucked with her.” The admission is forthright and vulnerable, at points palpable. The mix then turns into Future’s “The Percocet & Stripper Joint” and proceeds achingly into to Yeek’s “Love Can Be.”

The 50-minute selection is a dizzying, often contradictory testament to love and all the overlooked and unlikely places where beauty exists, a concept the artist has examined from various perspectives since his debut solo show. The figurative works in I Was Going To Call It Your Name amount to the visual equivalent of the mix’s sonic narrative. Paired together, they become a consideration of beauty in disparate states of being: as love, as hurt, as power, as possibility.

“Each and every one of these paintings are titled after a song that makes up the tracklist, checklist, and mixtape that we are hearing now,” Erizku said as Post Malone’s “Lonely” echoed through the gallery. One of the pieces, “Same Ol’ Mistakes,” is named after the slow-moving earworm from Rihanna’s ANTI. In the work, Erizku paints a black hand holding a red rose next to the stick-figure meme Bad Gal. “I always thought that logo was really funny. It’s one aspect of pop culture that I thought fit in my world,” he said, attesting to the gimmicky nature of the piece. “Rihanna is a voice of our generation, one of our ideals of beauty. You can see these two things co-existing in the same environment.”

But the paintings also extend beyond music to address formal concerns in Erizku’s emerging overture. Constructed out of Oriented Strand Boards, the paintings’ plywood canvases are typically used in cities as “Post No Bill” boards and speak to his interest in materiality. On one level, “the most important thing about this show is the introduction of figuration in my painting practice,” he said. “And then there’s this thing I’ve been doing for a really long time, which is this interest in color theory and also making an image through multiple mediums.”

Selections from I Was Going To Call It Your Name But You Didn’t Let Me, Nina Johnson Gallery.

Selections from I Was Going To Call It Your Name But You Didn’t Let Me, Nina Johnson Gallery.

Later, Erizku tells me about “Come and See Me ft. Drake,” a landscape painting that blurs the line between figuration and abstraction, and whose aspect ratio is derived from his training as a photographer. “You have the field, the sky with the blue and the clouds with the white, and then you have this,” he said, pointing to the brown manicured hand holding a red rose. “In a way I am kind of flattening space in this other dimension where this hand exists. I think, ultimately, what I am doing is thinking about how people are dealing with image making in 2016 and 2017.”

Before we part ways, Erizku reveals that the music is also about strategy. “The music allows me to make the white cube into something that’s more accessible to the people who I actually want to talk to — like the people who live in Little Haiti, the South Bronx, or Compton.” He offered a recent example. “I was in an Uber and got picked up by a black lady. She was like, ‘Oh, what kind of gallery is that? Is that a fancy gallery? Like, can I go in?’ I told her, ‘Yeah of course, come through.’ The woman came to the show’s opening and danced to the soundtrack. Maybe she wasn’t intimidated because she could relate to the music,” Erizku suspected. “She was like, ‘I definitely fuck with the black hands.’ If you fuck with the music you already feel like you are accepted in this space.”