Frank Ocean, Endless

Fresh Produce, LP

Fresh Produce, LP

When Frank Ocean’s Endless arrived by surprise on a Thursday night in August, the feverish anticipation for his way-overdue third release was soon replaced by confusion. Before the world, or at least the internet, could categorically classify it as “classic” or “trash,” it first had to figure out, What is it? As fans and skeptics tried to derive meaning from the 45-minute “visual album,” we didn’t know that it would only live as a continuous video on Apple Music, or that it would be followed up by Blonde a couple of days later. What we did know was that Frank had apparently spent his four-year hiatus learning carpentry.

In the days after Endless’s release, things crystallized: no traditional single would be plucked from it; no album edit with separate tracks would be available for purchase, and anyone wanting such a convenient and conventional experience would have to rip its audio and cut it up themselves. It was a shrewd move that presumably offered Def Jam a single source of revenue while providing Frank a clever exit from the label’s grip. But, because it was quickly followed up by the more accessible (in both format and content) Blonde, Endless was somewhat forgotten, chalked up as an artistic whim on Frank’s part, a palate cleanser before the Real Album.

But in reality, it was considerably the more forward-thinking of the two. While visual albums have become common — yet another way to “pull a Beyoncé” in the age of digital releases — Endless is unique for only existing as a video. The film — which found him building a staircase, a transparent allegory for the slow, difficult recording process both projects required — was not a marketing tool to advance sales and streams of the album or a visual companion that literally illustrated the musical narrative. The video was the album.

Just as it exploded the assumption that an album must be a sequential collection of distinct audio tracks, so did it challenge the notion of what a song should be. As tracks flow into and out of each other, Frank offers a handful of compelling alternatives to conventional song structure. A gentle, traditional five-minute cover of Aaliyah’s “(At Your Best) You Are Love” — itself a cover of the Isley Brother’s 1976 song of the same name — blends into “Alabama,” a pulsing song featuring vocals from Sampha and Jazmine Sullivan. It takes him only a verse and a coda to tell a detailed story that concludes with the loss of a virginity, perhaps his own. One of my favorite tracks, “Comme Des Garcons,” is a minute-and-a-half long; another, “Higgs,” isn’t much longer and is followed by a lengthy, didactic outro made independently by the artist Wolfgang Tillmans. All are given equal importance, all feel complete as they are.

We take it for granted that pop music should comprise some combination of verses and hooks and bridges, a relatively linear format that, following the rise of radio, allowed listeners multiple entry points into a song. Of course, artists across all genres have successfully diverged from that structure, but Endless is perhaps the most high-profile example in recent years. And as Frank’s woodworking was meant to suggest, it’s likely the most carefully crafted. — RAWIYA KAMEIR

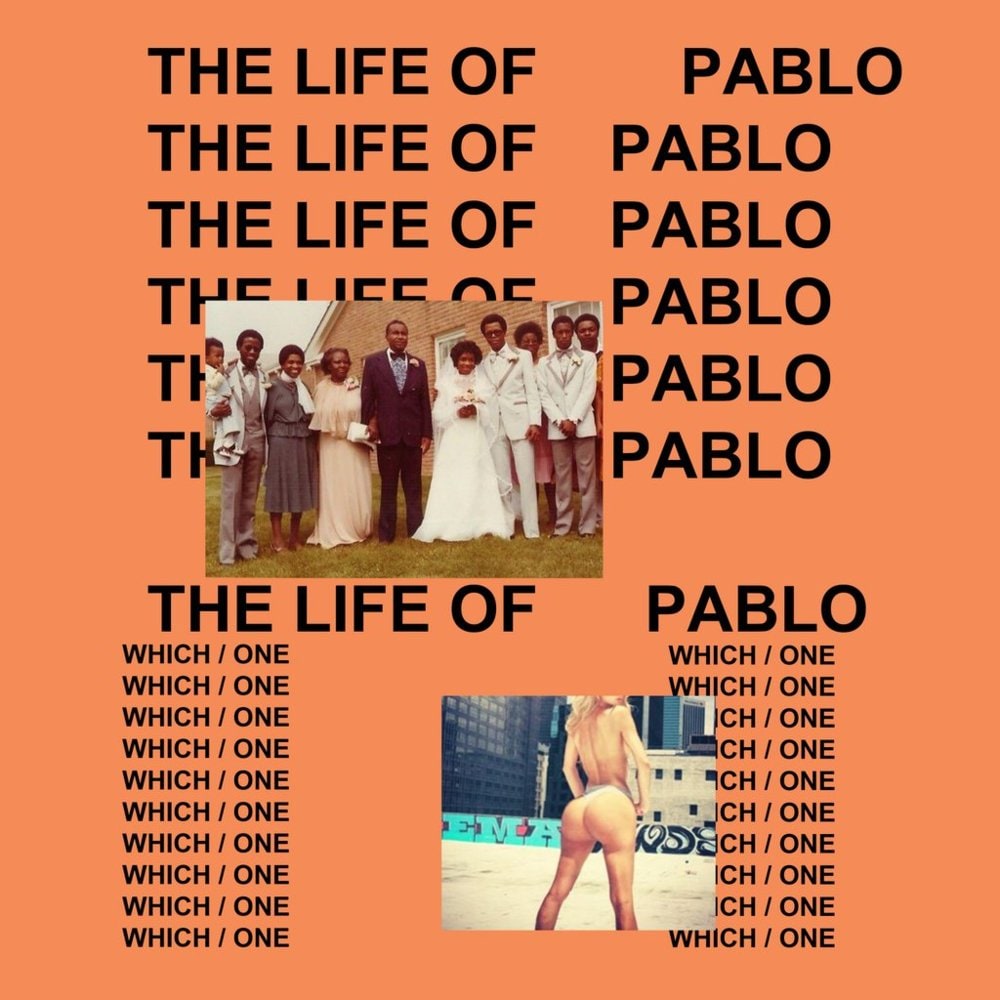

Kanye West, The Life of Pablo

GOOD Music

GOOD Music

It was a winter weekday afternoon, a strange time to be at Madison Square Garden. Even odder: the house lights were up and the place was half-empty, and silent, and still. On the floor was a massive drape in a tent-like formation, covering — something? I sipped Bud Light out of a very large plastic cup.

I like to force myself to remember: in the very last moments before it was revealed, I didn’t expect much from TLOP. On New Year’s Eve, Kanye had dropped an early version of “Facts.” Cumbersome and shouty, it felt like the worst thing I’d ever heard from him. More inauspicious was the collective histories of creative lives. Yeezus, his previous effort, had been a stringent punk marvel. It was also a kind of natural endpoint. From the round tones of his eager, earnest chipmunk soul to that — how much stranger, how much harder could he get? What worlds did he have left to conquer? If, at 38, Kanye West had given us all that he had, I would have accepted it. I would have expected it.

But then the drape fell and Ye took the aux cord. I’ve wronged many in my life, let myself down over and over again. But if there’s one thing I’ve done right, it’s hearing “Ultralight Beam” for the first time out of goddamn professional-American-sports-arena speakers.

In the months to come, running the album back over and over again, I’d have plenty of chances to clock the fundamentals that make Pablo singular. The swings from minimalist to maximalist — the ability to distill focus on one perfect noise and then, [Inception bong], give us everything all at once. The confessionals — shouted admissions, part joyous, part ugly, all stripped-bare and shot out of a T-shirt cannon. The full breadth of that thing: confused, sad, horny, alive.

There would be so much more to come, after MSG: release delays, TIDAL-exclusive windows stoking our desires, the tweaks and lyric-swaps and last-minute manipulations (that could, theoretically, if Kanye felt like it, go on to this day). The way he was transparently obsessed with his album echoed and inspired our own obsession. We never got a physical album. But we sure did get an album experience. — AMOS BARSHAD

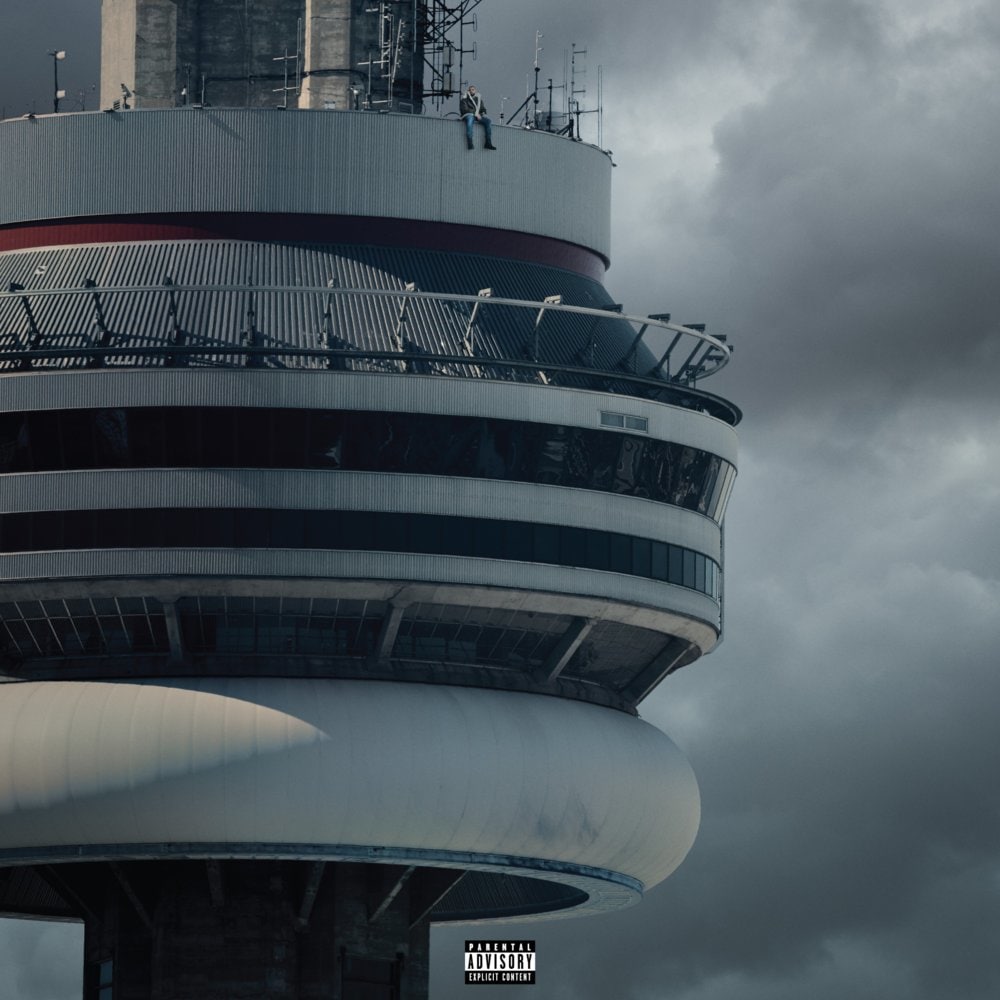

Drake, Views

Cash Money Records

Cash Money Records

When The FADER talked with him in late 2015, Drake made a point of describing If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, his mixtape from that year, as different from an album. “By the standard I hold myself and 40 to, it’s a bit broken,” he said. “There’s corners cut, in the sense of fluidity and song transition, and just things that we spend weeks and months on.” It seemed that Drake believed the most worthy ideas were the ones hands are wrung over.

And then, nine months later when Views arrived, it was criticized for failing to meet the perhaps outdated standard that had been set for it. It was too long, people said. The cover was too photoshopped and the accompanying art booklet too overproduced. Too many people were killed in the mini-movie. Most of all, it was argued that the universe of Views was too small, and its goal to find a shared dance via Drake’s experiences not sufficiently ambitious. It was not engaged enough with history, or politics, or the world.

And yet, who did not engage with Views? Since release it’s gone four times platinum, a fairy tale number by any measure. Its gathering of songwriters and guests and samples and meme-able moments remains an accurate portrait of what is now actually required to create new music memories on a global scale. And Drake, it turns out, seems to like to work a lot, as much or more as he likes to work deliberately. In December he’ll release More Life, a playlist presumably comprised of new songs from him and collaborators that will testify again to his taste and executive function. And in the years ahead, maybe he’ll realize that old notions of what an album should look like are as useless to him as old notions of authenticity. — NAOMI ZEICHNER

Kamaiyah, A Good Night in the Ghetto

Kamaiyah

Kamaiyah

Though its place in hip-hop has surely diminished since the dawn of streaming, the mixtape-as-album is definitely not dead. In the model of fellow Oakland native Kehlani’s Grammy-nominated 2015 mixtape, You Should Be Here, Kamaiyah made her definitive entrée with a carefully orchestrated, self-released free download. A Good Night in the Ghetto, like so many great debuts, introduced its artist to the world as if spontaneously fully-formed. It was certainly the first I’d heard of her, but she was hardly a newcomer.

The first two songs Kamaiyah released from the mixtape, “Out the Bottle” and “How Does It Feel,” were both produced by CT Beats, with whom she’d been collaborating since they met at a Youth Center eight years ago. Before her solo career took off, she’d spent years recording with the group Big Money Gang. Somewhere along the line, she caught the attention of fellow G-funk classicist YG, who ended up guesting on A Good Night in the Ghetto. His attention also brought her to Interscope, where he has a label deal and she is now signed. When that signing happened — and whether it preceded the release of her debut — is unclear. In an interview three months after the tape’s release, she told XXL “I’ve been on [Interscope] for a while now, but I just like to see the organic growth. I want people to grow with me because they think [it’s] organic.”

Suffice it to say, that brand-building strategy still works. A Good Night in the Ghetto was released just days before SXSW, where Kamaiyah performed at The FADER FORT (as Kehlani had the year before) and handed out thumb drives in the shape of burner phones. The tape’s cover art confirms her whole approach: it’s not her face you see in the photo, as she arrives at a house party, but the happy faces of her friends and supporters. You want to put Kamaiyah on because you want there to be a world where Kamaiyah gets put on. And maybe a label helped make it all possible, but the hell if that means she didn’t build it herself. “I put out a song and my life changed for real,” she says on the tape’s straight-up inspirational first track. “Aw shit, no more nights starving.” — DUNCAN COOPER

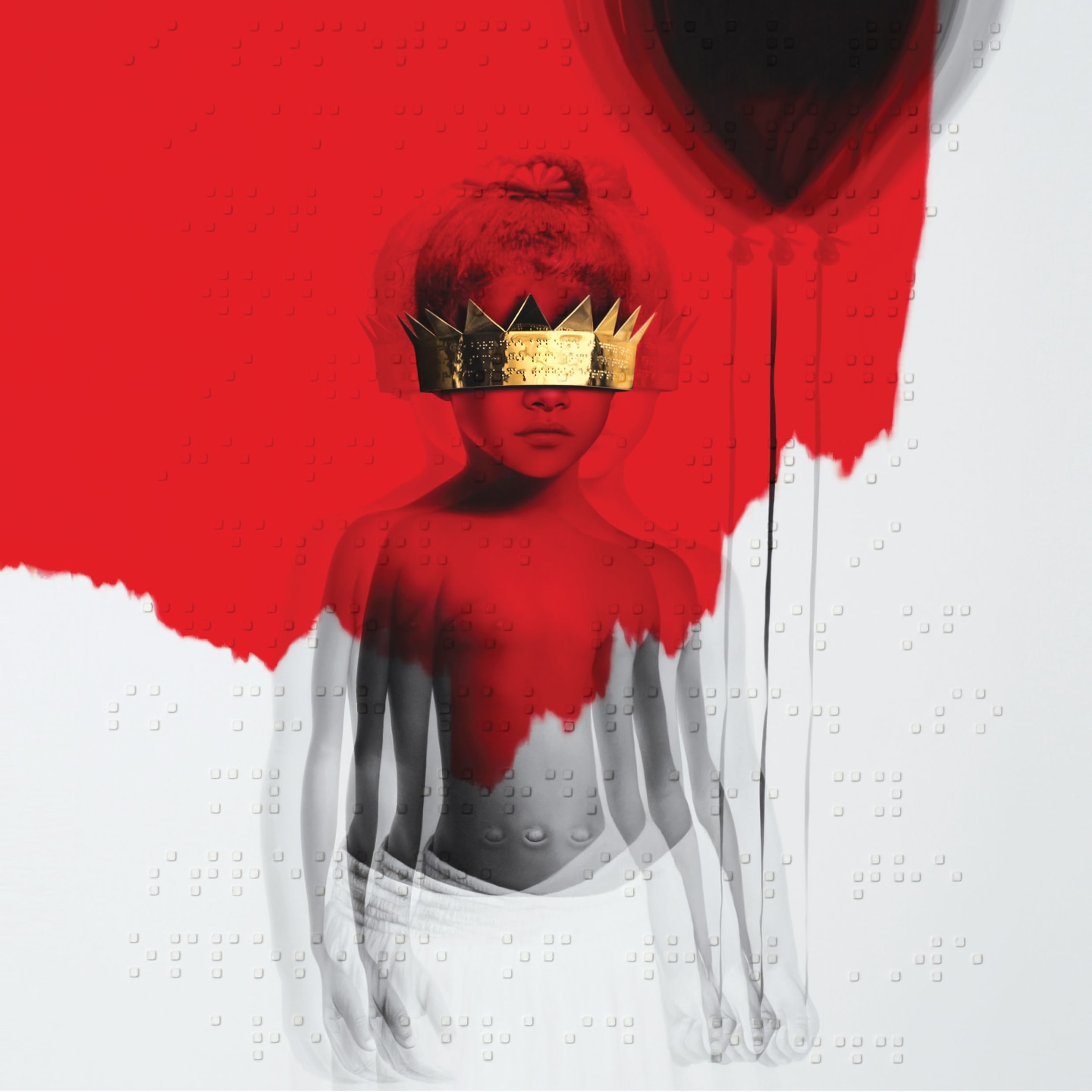

Rihanna, ANTI

Westbury Road Entertainment

Westbury Road Entertainment

Especially on the internet, an opinion made in an instant can curdle just as quickly. Not long after I tweeted that I hated ANTI on the night of its semi-botched release, I wondered if I had made a grave error. Eventually, the album not only grew on me, but began to seem like a savvy rejoinder to the lightning-fast era of careless judgements like mine.

It all adds up: the smoky atmospheres that sound almost unfinished, the ambivalent lyrics about intimacy issues and isolation, the shifts between dancehall and hip-hop and soul and psychedelia, the meandering tempo that, with the exception of first single “Work,” never picks up past a crawl. “I can just hear them now / How could you let us down?/ But they don’t know what I found,” Rihanna sang on the album’s Tame Impala cover, sounding eerily prophetic. The album came to mock me. She was right and I was wrong.

It’s hard to remember now, but at the time of ANTI’s release, Rihanna was under an almost-comical amount of pressure to release new work. It had been four years since her last record, and her fans were restless. The rollout was scattered: a series of belabored Samsung promotional videos and balloon emojis before a confusing leak. And yet ANTI was Rihanna’s careful way of handily meeting a moment that she hadn’t yet proven herself suited for: the post-Beyoncé landscape that asked more of artists than blockbuster bops.

I think it’s safe to bet that future critics will look at the time after the long shadow of Beyoncé’s ambitious visual masterpiece (and to Kanye’s Yeezus) as the new era of the pop concept album. Drake, Nicki Minaj, Chance The Rapper, and Kendrick Lamar have all since seemed to scale ever greater heights of ambition in their longform music. Because Rihanna — a great singles artist if there ever was one — wasn’t a natural fit for this zeitgeist, the surprise factor of ANTI’s wisdom is all the more reason why it’s truly a career-defining classic for the ages, and why a good album can feel more powerful than a few great singles. I was able to delete my take after its sentiment began to rot, but better artists don’t have that luxury: an album, unlike a tweet, is forever, especially if it’s as good as ANTI. — ALEX FRANK

Elysia Crampton, Elysia Crampton Presents: Demon City

Break Worlds Records

Break Worlds Records

The world of the electronic producer is often isolated. But for Demon City, Elysia Crampton enlisted four other producers: Chino Amobi, Rabit, Lexxi, and Why Be. All five could be considered part of a new global movement of digital composers who make protest, resistance, and identity politics integral to their music. Electronic music does not, and cannot, exist in a vacuum, and Crampton’s collaborative approach exemplifies this. Her work has been described as an “epic collage,” and by making a “solo” album that includes so many voices, she’s proven herself a master of gathering not just sounds, but ideas and perspectives.

From its warped piano to its skipping rhythms and natural disaster sound effects, Demon City feels like hell. It’s full of laughter that is not funny, cackles looped nightmarishly like a bad dream. And yet, even when it sounds like a hallucinatory death march, Demon City is a kind of utopian blueprint for what an electronic album can be in 2016: free of ego, and representative of something more than the achievements of a single person.

To describe her music, Crampton has used the term severo, Spanish for “severe.” That quality makes Demon City a soundtrack for a year as difficult as this one, and not simply because it’s noisy and cathartic. As Crampton has said during her live show, “The time for revolution is now.” Her cooperative album calls attention to the like-minded people who exist all over the world — people who are oppressed in different ways, people who also want to fight and change the shape of reality. In its conversational form, it serves as a reminder that the only way to move forward is together. — AIMEE CLIFF

Beyoncé, LEMONADE

Parkwood Entertainment

Parkwood Entertainment

“Sorry,” a transitional track on LEMONADE’s Afrodiasporic journey from betrayal to redemption, is an anthem of unapologetic refusal, and it offers a useful response to recent calls to unify around Trump: “Hell nah.” On the other hand, its flickering refrain — “Sorry… I ain’t sorry” — admits resistance won’t be easy. Bey can tell her lover to “suck on my balls,” but she’s also hiding her tears; she can insist “I ain’t thinking ‘bout you,” but the claim itself gives her away. “Sorry” links the pained bravery of 2006’s “Irreplaceable” with the swagger of the blues, and so captures the emotional tenor of the present. In the wake of the election, LEMONADE sounds different than it did upon release, in April. It’s less like a straightforward march toward healing, and more a reminder that it is hard to live with and through history: to experience social betrayal as personal heartbreak, to be sorry and not sorry, scared and not scared, at the same time.

And LEMONADE’s deep engagement with history is what ensures its continued relevance to a moment defined by struggles for justice. Beyoncé has always been a consummate student of black musical history, whether recalling eight decades of black divas at the 2008 Grammys, alluding to Sam Cooke’s “Wonderful World” on “1 + 1,” playing Etta James in Cadillac Records, or dressing up as Salt-n-Pepa for Halloween. But not until LEMONADE has her archive been so deep and her canvas so wide. Musically and in the accompanying video-album, Beyoncé cites historical and cultural events from slave uprisings to Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust. This album echoes the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s by demanding that people learn black (women’s) history before commenting on black (women’s) art — hence the creation of the LEMONADE syllabus.

As a self-consciously epic album for a self-consciously historic moment, LEMONADE embodies what Daphne Brooks described as a “new wave of black pop protest music” while also initiating a banner year for black cultural production — from the WGN series Underground, to Ava Duvernay’s cable family drama Queen Sugar, to the critically acclaimed film Moonlight, to black MacArthur “geniuses,” all the way through to Solange Knowles’s album A Seat at the Table.

And yet: if one of the most scrutinized artists in history can keep us guessing whether the album had anything to do with Jay Z’s infidelity; if she can storm the Super Bowl field at halftime with a group of black women in Black Panther garb; if she can dance without flinching while water gets kicked in her eyes, she seems able to do anything. And the greatest gift of her work, particularly in a year like this, is that it makes us feel like we can, too. — EMILY J. LORDI

David Bowie, Blackstar

Columbia Records

Columbia Records

On the album he made to say goodbye, his 25th, David Bowie showed a sharp knowledge of the way that we experience death in the modern age. He knew that his passing would be analyzed with the same fervor as his Ziggy Stardust or robo-gigolo looks in the ’70s. So he made a spectacle.

The most sparse moments of Blackstar speak the loudest, even when they are a little on the nose. The video for “Lazarus” shows Bowie lying frail in a grubby hospital, his head wrapped in gauze bandages. In another defiant simulacra, he performs the dance moves of Thin White Duke, a character he created in 1976. Though he still pulls them off like no one else, watching is a sobering experience.

During the private battle with cancer that ended his life, Bowie spent much of his time working on Blackstar. The album was delivered with darkly poetic punctuality, two days before Bowie died on January 10. An occultish, Jodorowsky-like video for the title track riffed on his ’70s extra-terrestrial obsession, and skull-centered rituals and figures gyrating on crucifixes. It looked to the past while offering a grim teaser of what was to come.

Yet despite its preoccupation with mortality, Blackstar is far from bleak. There’s a fascinating sense of invention and fun in the wordplay, and the synths pulse with electricity. Stately closing track “I Can’t Give Everything Away” samples an elegiac harmonica line used in "A New Career in a New Town" from Low. (If the earlier album opened a new creative chapter, Blackstar is the punctuation at one’s end.) And yet for all of these breadcrumbs, much of Blackstar evades linear interpretation. Fans are still trying to find messages from beyond the pale in its tricked-out physical edition. It’s as if Bowie was saying, “OK, well, catalog this!” — with a gleeful knowledge that much of Blackstar, like its maker, would remain inscrutable. — OWEN MYERS

Solange, A Seat At The Table

Columbia Records

Columbia Records

Police fatally shot Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, and Korryn Gaines within the span of 30 days. By Summer’s end, like my peers, I was mad. I felt ignored. I was exhausted by the fashion designers and white celebrities who appropriate my culture. I wondered: did America actually care about the community of people who looked like me? Then in September, and not a moment too late, Solange beautifully unraveled all of that built-up angst. Somewhere, I heard black folk let out a collective exhale.

A Seat at the Table, which was preceded by a super-limited-edition photo book that teased some of the gorgeous visuals that would populate the subsequent music videos, makes a place for “moments of grief, and being able to be angry and express rage, and trying to figure out how to cope.” It creates a space to lay down burdens and have vulnerable conversations about self-worth, sisterhood, and community. When I heard Solange sing “All my niggas got the whole wide world/ Made this song to make it all y'all's turn/ For us, this shit is for us,” her loving emphasis on the word “us,” I cried. I felt proud to be black ten times over. The interlude testimonials are key, too; they advance the narrative and offer wisdom, like historical documents of black life.

By allowing Solange to share her truth, this album holds more than enough power to restore the rest of us. I know that because of it black people, especially black women, also didn’t feel alone. In a time when black voices are still silenced, Solange’s authority empowered listeners. Her intention to foster meaningful exchanges is an impetus for black women to honor their pain, heal, love, and rise in their power. A Seat At The Table feels like freedom, because it’s made of all the magic that has been, and will always be, for us and by us. — LAKIN STARLING

Various Artists, Epic AF

Epic Records

Epic Records

In July, Epic updated the label compilation format that rap imprints pioneered decades ago, releasing Epic AF, an album that’s more like a playlist. The strategy was uncomplicated but clever: instead of waiting for curators at Spotify, Apple Music, or Google to add their songs to big playlists, Epic went ahead and collected viral smashes and prospective hits from its own roster. At the time, loosies like French Montana’s “Lockjaw,” DJ Khaled’s “For Free,” and Kent Jones’s “Don’t Mind” had been streamed millions of times, but were not yet tied to official album releases from those artists. Brought together by the compilation, the singles had more visibility and a greater power on the charts: as of 2014, Billboard has counted 1,500 streams or 10 song downloads as one album sold, and these updated chart rules allowed Epic AF to reach the Top 10 four times over the summer, without the album ever being made available for purchase, physically or otherwise.

Perhaps this signals a sea change in the way major labels will release and market music, especially from artists working outside of the album format. Epic is reportedly planning a pop-oriented compilation project, Drake has announced a “playlist project” to be released in December, and Def Jam has just released its own compilation, Direct Deposit Vol. 1. As traditional album sales wane and streaming continues to dominate music consumption, Epic AF serves as an important case study in adaptability. The battle over streaming exclusives dominated headlines this year, and albums like Chance The Rapper’s Coloring Book and Frank Ocean’s Blonde positioned streaming services as a remedy to major label exploitation. Epic AF is a pragmatic response to this dynamic that both confirmed streaming’s position and offered symbiosis as a path forward. — BEN DANDRIDGE-LEMCO

Archy Marshall, A New Place 2 Drown

XL/ True Panther

XL/ True Panther

Archy Marshall doesn’t always like to talk about himself. In certain cases, reporters have been left to piece together details of his interior life using context clues: his brooding lyrics, his onstage antics, and the lengthy, pointed silences between his words. The prolific, creatively restless songwriter’s attitude toward press and social media has long seemed to indicate a stubborn sort of purity: let the art speak for itself.

In December of last year, the 22-year-old best known as King Krule released a multidisciplinary art project called A New Place 2 Drown via XL and True Panther, which we’re including on this list because it feels more like a 2016 artifact. The project’s physical centerpiece is a 208-page book that Archy made with his older brother Jack. A meticulously collaged collection of summery candids, surrealist doodles, and autobiographical poetry, it’s bleakly childlike and a little bit punk, like an oversized art zine. “I like the physicality of it,” he told NPR. “I like the fact that you can touch it and lick it and do stuff to it.” The soundtrack finds Archy singing the book’s poems amid hip-hop beats and nocturnal murk. The result is morbid, funky headphone music, like the inner monologue of a stoner with a lot on their mind. It would be a great record on its own, but it works especially well as a companion fragment, a piece of something bigger.

A New Place 2 Drown is old-school in form and forward-thinking in scope; together, the Marshall brothers dreamt up a different kind of oversharing, one that has nothing to do with Instagram updates or podcast interviews. It seemed to say: If you’re going to let the art speak for itself, why not make the art as immersive as possible? The project feels deeply personal; the king of aliases — Archy has a dizzying number of them — released it under his given name, if that’s any sign. There’s a pretty film directed by Will Robson-Scott that goes along with the book and album, too, offering a too-short glimpse into the brothers’ South London lives. At one point, they hit golf balls off beer bottles in a wide-open field. Even though it’s overcast, it still look like a perfect day. — PATRICK D. MCDERMOTT

Young Thug, JEFFERY

300 Entertainment

300 Entertainment

If streaming data is the only metric that really matters in music — and let's say it is — then to have a successful album means making it as clickable as possible. And as any teen who has ever shopped in Hot Topic knows, the albums with the longest shelf life are the ones with the most iconic covers.

Seeing the cover of Young Thug’s Jeffery for the first time, I was reminded of a quote from Epic Records C.E.O. L.A. Reid’s recent memoir. “One thing I know about pop music is that when you can create a character that lives in your songs, you have it made,” Reid wrote, pointing to the successful styling of Michael Jackson’s sequined glove, and Avril Lavigne’s white tank and tie. “You can make your songs hits, you can make yourself famous, but until you’ve created a character, you haven’t cracked the code of culture.”

Young Thug has always been Jeffery, but in donning that flowing, purple garment by Italian designer Alessandro Trincone for the Jeffery cover, he introduced himself anew. The album serves as a reset button; it’s a complete and cohesive world in which all of Thug’s multiplicities can exist. Its tracks are named for the artist’s heroes, but they might also be seen as a list of attributes that he intends to possess: the crossover appeal and longevity of Wyclef Jean, the bravado of Floyd Mayweather and Gucci Mane, the sex appeal of Rihanna and Future, and the creativity of Kanye West. (Also, the virality of Harambe.)

As himself, Thug holds strength and softness with equal, interchangeable weight. With the best hooks of his career and ad-libs falling like the folds of his violet train, Thug created a powerful character that can twist into anything, and made a fertile home for it. — MYLES TANZER

Babyfather, BBF: Hosted By DJ Escrow

Hyperdub

Hyperdub

Dean Blunt has a long history of reconfiguring the live performance space. For the debut LP from his rap side project Babyfather, he similarly subverts the traditional album format. BFF: Hosted By DJ Escrow is more akin to a pirate radio show fronted by Blunt’s perky Babyfather partner, whose on-air patter breaks up Blunt’s smoked-out atmospherics. A broadcast studio is evoked with a catch of the breath, the puffing of a spliff, and the echo of Escrow’s mic. Blunt’s voice is embedded in the songs, underscoring the fact that it’s his records that Escrow is spinning through the static.

The show opens with “Stealth Intro,” which contains a spoken word sample that is the backbone of BBF: “This makes me proud to be British.” The sentiment is repeated at an uncomfortably slow and steady pace for the duration of the almost five-minute track, and reappears on two other songs, “Stealth” and “Stealth Outro.” When I first heard it, I didn’t yet understand the sample’s providence. BBF came out in April, in the middle of Britain’s European Union referendum campaigning; against that context, I assumed the “Stealth” speaker was a skinhead racist. In fact, it was the voice of Craig David, from a MOBO acceptance speech for Best R&B Act in the year 2000. The previous years had seen separate award categories for international and homegrown acts. For the first time, David was up against American artists who were all over U.K. radio. He accepted the award wearing a chunky red jumper with the words “BUY BRITISH” emblazoned on the front.

Sixteen years on, Blunt’s re-contextualization of David’s somewhat throwaway comment loops it over and over as if to examine it from every angle. What does it mean to be proud of being British today? What has it always meant? Just two months after BBF dropped, over half of Britain voted to leave the EU, paving the way for a sharp increase in racist attacks. Blunt’s fans like to think he’s a prophet; maybe he could smell it coming. BBF, then, is a podcast from a pre-Brexit world, steeped in the racism that white Britain has avoided addressing for so long. There are some pointed sonic clues — a trickling harp that evokes the English aristocracy underscores the opening track and decorative chimes fall like icy tears on “Killuminati” — but it is Escrow’s off-the-cuff exclamations that light the way. On “The Realness,” he borrows a line from New York rapper Cormega’s 2002 song “Love In Love Out” that elevates the album’s transmission to time-capsule status: “Trust is a luxury I can’t afford.” — RUTH SAXELBY

Bon Iver, 22, A Million

Jagjaguwar

Jagjaguwar

After my wife Stacey got sick, she had so many tests where she had to be on an MRI machine or a CT scan, and she chose to put on Bon Iver to relax. We used his music for calm and serenity. 22, A Million came out right before she passed away in August. Since then, it’s provided me a form of healing and comfort. I’ve gone back to this album over and over again, because it’s become so directly linked to that experience. When I listen to the music now, it feels like I'm still with her. There's still a connection to her, through the music.

This album creates a layered fabric that is not very familiar to anyone’s natural ear. The songs are extremely dynamic; they change dramatically and flow into each other. I love that he tried to piece together a french horn, and an 808, and a harpsichord with vintage recording equipment, and that his goal was to make music that didn’t sound like anything that people had already heard. I think I was able to kind of tap into that abstract nature emotionally, which did give me a lot of peace. It’s like a blanket. Early in the morning, late at night, in the afternoon — I can put this album on and it actually takes my blood pressure down. There are moments in these songs that prompt me to feel something physically in my body. The album is not entertainment, for me. It’s a form of understanding something that there is no real way to understand.

This morning, I listened to the album for the first time in about a week. And it’s started to feel different now, listening to it. Over time, it’s going to shift a lot, the way I process this piece of work through my ears, and my brain, and my heart. But I think it will always bring me back to a very crystallized time of my life. Which is, I think, the ultimate compliment. Any good artist creates music for themselves, but also because they want people to have emotion, and engage with their music on different levels. This is as deep of a level as I ever engaged with any single piece of music. — ANDY COHN

Frank Ocean, Blonde and Boys Don’t Cry

Boys Don't Cry

Boys Don't Cry

Since Frank Ocean put an ’80s BMW on the cover of his debut 2011 mixtape, automobiles have been a motif in his work. But Blonde, and its limited-edition luxury “zine” Boys Don’t Cry, provide colorful new context. “Raf Simons once told me it was cliché, my whole car obsession,” Ocean writes in the zine’s preface. “Maybe it links to a deep subconscious straight boy fantasy. Consciously though, I don’t want straight — a little bent is good.”

On the sweetly nostalgic “Ivy,” Ocean reminisces about his teenage days: “Safe in my rental like an army truck back then/ We didn’t give a fuck back then.” But in adulthood reality hits hard, and both Blonde and Boys Don’t Cry are ultimately about Ocean’s experiences as a queer black man, and what it means for such a person to be behind the wheel in 2016. In the zine, there’s poem called “Boyfriend” that describes casual everyday intimacies with a partner, like driving in his “lil bucket” and holding onto each other tightly. “We don’t want no problems,” he writes.

For LGBTQ folks this is often endgame enough, and this year, we’ve more acutely felt the desire to be carefree. We have needed strength and shelter from the hateful rhetoric of lawmakers, and the violence that has claimed our lives. On Blonde there’s emotional heft to even the most plainly put sentiments, like “Been waiting on you all my night.” But Ocean’s directness feels particularly powerful when he talks about the specific codes of gay lust, like the lover in “Nikes” who might be fucking his roommate, or when he casts himself as the “boyfriend in your wet dreams” on “Self Control.”

In the private sanctuary of a car, you can play your music loud, travel where you like, and invite anyone you want to join. With Blonde and Boys Don’t Cry, Ocean created a personal cocoon, and invited listeners to climb inside. Four years after Ocean grappled to reconcile faith with his sexuality on “Bad Religion,” I’m grateful that he got to a place where he could write with “no, like, shame or self-loathing.” One day I hope that all queer people don’t have to face the hurdle of society’s shame. But in 2016, hearing Ocean’s pride reassures me of my own. — OWEN MYERS

Future, Purple Reign

Freebandz

Freebandz

For years, Future released free music in January on LiveMixtapes. There was Dirty Sprite in 2011, Astronaut Status in 2012, FBG: The Movie in 2013, and Beast Mode in 2015. (In January 2014, he was going to fashion shows with a pregnant Ciara and preparing for the release of Honest.) In January 2016, he dropped Purple Reign. (It was a free release, but produced the official single “Wicked.”) Future announced the tape on Twitter and LiveMixtapes put up a countdown clock, promising it would arrive within hours. When the countdown ended there was no tape; a day later it materialized.

This was far from the only fumbled rollout of the year, but even so it felt like the end of a chapter. Now that streaming platforms pay top dollar for content exclusives, and “retail mixtapes” are the norm, free tapes and the sites that host them just aren’t what they were. If Future releases something in January 2017, it’s hard to imagine him choosing LiveMixtapes as an exclusive partner. Since that’s the community where I discovered and came to love him, that makes me sad. But it also points to a future where artists have an opportunity to sell everything they make, no matter how off the cuff. May they stay as in control of that racket as E-40 (who has long sold multiple double albums each year) and Gucci Mane (who has released mixtapes for free and for sale simultaneously) have been for years. — NAOMI ZEICHNER

Chance The Rapper, Coloring Book

Chance The Rapper

Chance The Rapper

If you were to connect the histories of 2013 and 2016 — pivotal years that bookend the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the rise of Donald Trump — you’d do well to start with “Acid Rain” and conclude with “Blessings (Reprise),” the final track on Coloring Book that finds Chance finally free of the figurative storm that engulfed his early years. Until recently, I had considered “Acid Rain” Chance’s most important song, if not his outright best: at turns haunting and wistful, the young Chicagoan ambles through an impassable tempest of self-doubt, friendship, and blood-splattered childhood memories. He culminates the track with a devastating line: “Rain, rain, don’t go away.” In occasional flashes of candor, the song feels utterly hopeless — devoid of all the things we have now come to associate with Chancellor Bennett: love and God and golden heaps of joy.

On Coloring Book, liberation takes varying configurations. Chance isn’t just free from the Xanax-addled fog that once consumed him, or from the bad choices that outlined much of his time in Los Angeles before he moved back to Chicago to record what would become the most progressive gospel project of the last decade. He’s also totally untethered from any of the major labels that have tried, and still try, to sign him. Released for free via Apple Music — a dreamy situation that essentially affords Chance label backing without all of the politics that come with it — Coloring Book is about personal and collective deliverance in its most sanctified forms. It’s about having the faith to go on. It’s hearing, “Are you ready for your blessings, are you ready for your miracles?” and responding with an arms-wide-open yes, more than willing to bear the weight of all that comes with that declaration: the fame and the money, the people with ill intent trying to pluck all of the good fortune from your life.

To be an in-demand artist in the modern era that is not dependent on big-label aegis, you’ve got to have time-tested faith. Faith that has seen demons up close and laughed hard. Faith that knows the honest-to-God burden of responsibility — for your fam, your crew, your city — and just how heavy it gets at night. Faith that does not waver. Which is to say: you’ve got to believe. For decades musicians have relied on any semblance of self-belief to stand firm in an industry that seeks to commodify every inch of one’s creative force. Yet in today’s agitated climate, having the faith to not give in and use what you’ve learned from past mistakes to forge a brighter path in a world that has taken a dark, unfamiliar shape is so exceptionally rare it feels radical. Thankfully, it’s one sentiment Chance The Rapper so wonderfully reminded us of in 2016, the year of our Lord. — JASON PARHAM

Francis and the Lights, Farewell, Starlite!

KTTF

KTTF

A handful of 2016’s biggest records used an audio software tool called the Prismizer, which was developed by Francis Farewell Starlite, a.k.a. singer Francis and the Lights. If Auto-Tune is like butter, able to be spread over vocals to make them rich and tasty, then the Prismizer is butter’s clarified form, turning a single vocal take into a chorus of kaleidoscopic hymns. Chance The Rapper used the Prismizer on Coloring Book’s “All We Got,” where he it made him sound like he was backed by a thousand Kanye Wests. Bon Iver poured it all over 22, A Million, and it pops up on Frank Ocean’s “Close To You,” making the Blonde Stevie Wonder interpolation more invention than tribute.

But the person with the best grasp on the Prismizer’s power is Starlite himself. Francis and the Lights’s Farewell, Starlite! serves as a quasi-instruction manual for one of music’s most powerful new tools. Under the machine’s spell, schmaltzy lyrics like “It's alright to cry, it might make you feel better, baby” feel authentic. The album has different moods — there are teary ballads and calls to the dancefloor — but thanks to Starlite’s vocal manipulator, they all feel cut from the same rosily distorted cloth.

Still, Farewell, Starlite! has a triumphant standout in “Friends,” a perfect three-minute song about the final moments of a breakup. It found chart success in part because of its video, in which Starlite, Kanye West, and Bon Iver commit to some seriously dorky choreography. Sung by Bon Iver and Starlite, the song’s “we could be friends” refrain is meant as a hopeful message for parting lovers. But under the glow of the Prismizer, it sounds like that message is being sung by a car full of actual friends. Now that’s a technology worth believing in. — MYLES TANZER

Tanya Tagaq, Retribution

Six Shooter Records

Six Shooter Records

Tanya Tagaq transforms her community’s tradition of Inuit throat singing into an ambiguous and contemporary stew of genre. When she won Canada’s top music prize in 2014, she had released four albums, but remained relatively unknown. At the acceptance ceremony for that prize, she performed in front of a projection of hundreds of names of missing and murdered indigenous women, a decades-long injustice the native activist movement Idle No More brought to public consciousness. Speaking to The FADER this year about representing her culture and politics as a public figure, she said: “When it’s who you are, it’s like, Do you feel strange representing your legs as you walk? It’s just part of who I am.”

Tagaq’s 2016 album Retribution is, explicitly, an album about human destruction — of all kinds — but listening to it also provides an attack on illusions: the kind that get us through the day, and the ones nation-states hide behind to defend the indefensible. “We turn money into God and salivate over opportunities to crumple and crinkle our souls over that paper, that gold,” Tagaq carefully intones on the title track, savoring every word like it’s flavored with justice. Sometimes her vocals can overwhelm these incisive moments. Each growl, yelp, hum, and moan contributes to a fervent glossolalia: even if she shared her language with you, this isn’t an argument you could win.

This year people around the world have felt in their guts that something is wrong, and have voted for enormous political shifts. For this moment, Retribution is revenge fantasy, and also the pangs of real change. — JORDAN DARVILLE

Kaytranada, 99.9%

XL Recordings

XL Recordings

After spending a few years on the road off the strength of his remixes, Kaytranada returned to his mother’s house in the Montreal suburbs and created a deeply personal album in creative deference to his formative influences, synthesizing experimental, bass-heavy sounds and skipping restlessly between house, R&B, hip-hop, soul, disco, and funk.

At its heart, 99.9% is indebted to the sprawling and disparate beat tapes that helped J Dilla and Madlib make their names in the early aughts. Glitzy disco dramatics on "Track Uno" lead to the nostalgic "Breakdance Lesson N.1," influenced by the lo-fi pop production of early Prince and Michael Jackson demos. Like his crate-digging idols, Kaytranada is a prolific collaborator, and 99.9% is laced with skilled vocalists (Craig David, Vic Mensa, and Anderson. Paak) who add stories and textures in interesting spaces.

But it’s on the track “Lite Spots,” where an old, mostly forgotten song (Brazilian singer Gal Costa’s 1973 track, “Pontos De Luz”) is flipped into something fresh, that we get to the core of 99.9%'s purpose. Kaytranada chose to come home and make this album in a studio beneath his tight-knit family’s kitchen. There, in the place where he fell in love with music, channeling the honesty and manic productivity behind his early wins, Kaytranada created an album that earnestly builds on the work of his heroes. It offers a touchstone for how young musicians, who have all of musical history at their fingertips, can still find ways to innovate. And it feels like coming home. — DAVID RENSHAW

Blood Orange, Freetown Sound

Domino Recording Co.

Domino Recording Co.

In 2015, Dev Hynes released a song called “Do You See My Skin Through The Flames?” It was a jazzy sermon from the middle of gentrified Brooklyn, about how the supposed color blindness of his white fans and white friends wasn’t just alienating, but also part of a climate of racialized violence that has left many black men and women dead. On his second album as Blood Orange, Hynes grafts this idea and the traumas of identity into a personal narrative that implicates everyone. Freetown Sound is, in his words, an album for anyone who’s been “told they’re not BLACK enough, too BLACK, too QUEER, not QUEER the right way, the underappreciated.”

As Blood Orange, Dev created a project steeped in the soft-synthed nostalgia of ’80s and early-’90s pop, and the specific stories on Freetown Sound feel like they started off as scribbled entries in a teenage diary from that same time. This album is the sound of pain — inflicted by the limits of masculinity and vulnerability, of shadeism, and liberal racism — that Dev has been holding onto for years. “All I ever wanted was a chance for myself, been chewed up but it makes you proud,” he sings on “Chance,” before singer Kelsey Lu chimes in to narrates his inner voice: “You’re the dark skin nigga in a sold out crowd.” Women feature heavily on Freetown Sound — poet Ashlee Haze, Empress Of, Zuri Marley, Nelly Furtado, Carly Rae Jepsen — and they articulate the record’s most achingly deep and vulnerable moments, releasing Dev from the burden.

Prettiness isn’t exclusive to femininity. And Freetown Sound distills the wider public conversation of how black skin and identity is persecuted politically and criminally, by returning to the individual experience. This record isn’t big ideas rhetoric; it’s about the one-to-one interactions, from childhood onward, that lead to permanently fractured notions of beauty, and belonging. — ANUPA MISTRY

Anohni, Hopelessness

Secretly Canadian

Secretly Canadian

The best science fiction writers, from Octavia E. Butler to J. G. Ballard, are keen observers of the present. Their job is to put the everyday under a microscope to help us all see where we are going. On Anohni’s debut solo LP, Hopelessness, she assumes a similar role, sketching out stark endings to real-life tales of unchecked human behavior. It is an alarm bell of an album, one that knows silence is complicity, especially when it comes to assessing the damage that our species has wreaked on the planet and its inhabitants. As she said in an interview back in the spring, “If we can't even say where we are, how can we ever hope to shift our course?"

With a mix of ecstatic rage and regret, Anohni sings about climate change, mass surveillance, and the patriarchy. She sees rhinos “crying in fields” (“4 Degrees”), corporate punishment as “an American dream” (“Execution”), and humanity as a “virus” afflicting the planet (“Hopelessness”). Yet there’s little preaching. In her forties, Anohni knows better than to think a sermon could attract anyone but the already-converted. Instead, she tries reverse psychology in an attempt to jolt casual listeners into action: “I wanna see this world, I wanna see it boil.”

As all responsible adults know, a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. To that end, Anohni opted for a sharp departure from the austere ballads of her Antony and the Johnsons years. Instead, she employed two of electronic music’s most divergent producers — Hudson Mohawke and Oneohtrix Point Never — to help wrap warnings of man-made destruction in boombastic bass and twist messages of conservation around gaudy candy cane hooks. In the listener's body, that clash of form and content hopes to reverberate with the clarity of a mic drop.

Despite the resignation of its title, Hopelessness is a body of work that deeply desires to reach receptive ears — sometimes to a fault. Opening track “Drone Bomb Me” wants to raise awareness of the atrocities of President Obama’s drone program, which has likely killed hundreds of civilians in countries including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. Yet, to squeeze that ugly truth into a pop song format, Anohni uses a fictional narrative about a 9-year-old Afghan girl whose family was killed by a drone bomb, clumsily projecting her own white guilt onto an imagined victim.

Six months on from its release, the future that Hopelessness warns of has swung into sharp focus with the the election of Donald Trump. We need dissenting voices now more than ever — protest works, and protest albums, a somewhat abandoned form in the past decade, can help galvanize action. As much as Hopelessness is a message in a bottle, bobbing around in a churning sea, it is also a lit match, designed to breathe fire into the bellies of young listeners. And if it has one message we should all take up as a mantra, it’s this: “Never again give birth to violent men.” — RUTH SAXELBY

21 Savage & Metro Boomin, Savage Mode

Slaughter Gang

Slaughter Gang

Savage Mode is a surprisingly pretty piece of music. Everything, including the actual tempo, is tempered, understated, resolute. Throughout, Savage is often nearly whispering. It’s a prickly, peculiar, low-register snarl; in its restraint, it comes off all the more menacing. Notwithstanding, there’s nothing particularly novel in Savage’s street talk. But there is something altogether singular about him, something powerful. It's in his delivery — lean, tight, agnostically flat — that we feel the potency. “I smashed the stripper in the hotel with my chains on,” he huffs on the chorus of the song “No Advance.” He utters the line with a grim, slight singsong. In its weariness, it’s intoxicating.

At times he goes to extremes that feel like self-aware gallows-humor. He peppers in sly, amusing little references to remind you he does, in fact, know that the outside world exists. (How can you not smile at “I sit back and read like Cat In The Hat/ 21 Savage, the cat with the MAC.”) But his dominant mode is steely-eyed focus. He’s a young man, just barely 24 years old, enjoying the first flushes of fame. And he sounds like a returning vet of war, bruised and beaten, quietly hellbent on telling you his tales.

32 minutes. 9 songs. Not a second too long, not a second too short. A cohesive through line. Each part supporting the whole. In an era of big statement albums, it’s efficient. Truly, a piece of music. Hear a snatch here and there, and you wouldn't get what this is about or why it matters. Turn off the lights, though? Light some candles? Immerse yourself in the whole? And a small world opens. This is gully, gnarly, shit-talking street-rap for your early morning meditation. — AMOS BARSHAD

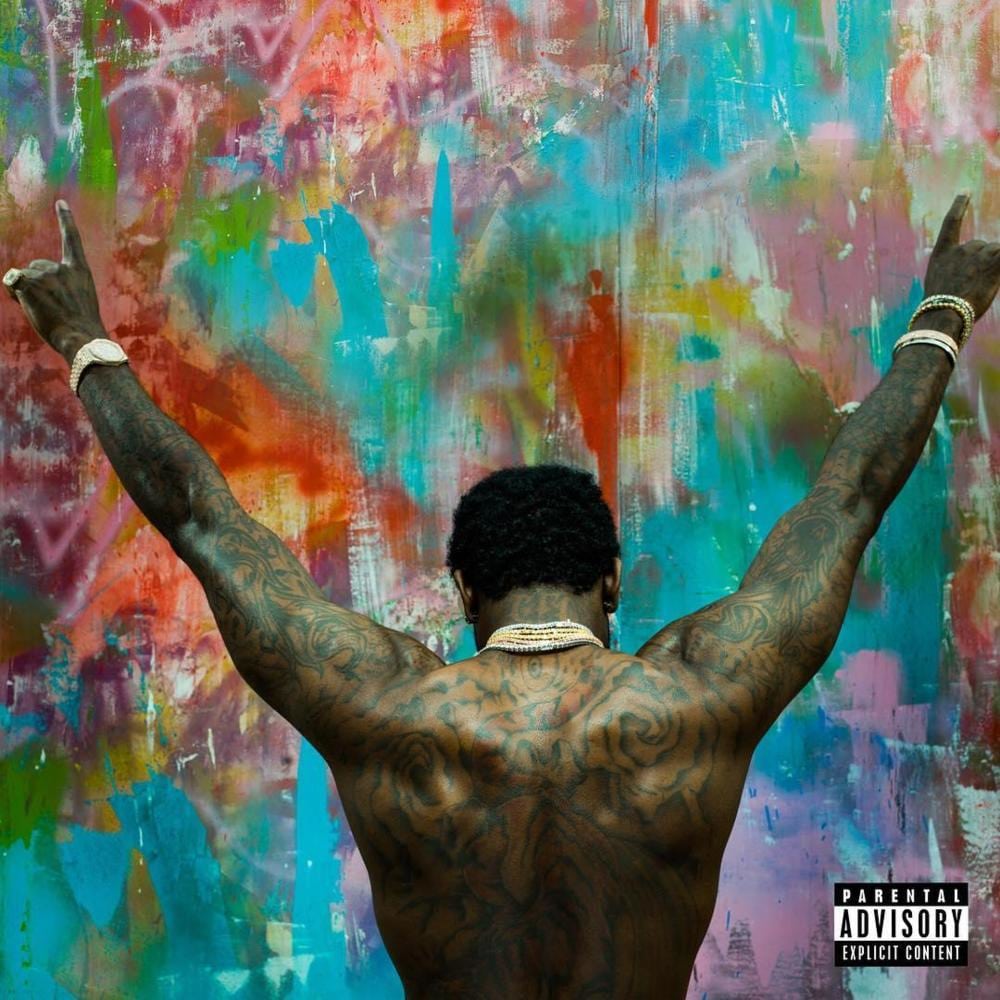

Gucci Mane, Everybody Looking

Atlantic Records

Atlantic Records

After spending over 1,000 days in prison, one of the most preternaturally gifted lyricists of all time re-entered a world that, in his absence, moved away from him in subtle ways that he wouldn’t so instinctively get. Though Gucci Mane’s engineer had been using previously recorded verses to cobble together collaborations over the years with Fetty Wap, iLoveMakonnen, and others, Gucci hit his house-arrest home studio in May deprived of the experience of fully and firsthand absorbing the contortions rap had made since 2013.

Recording Everybody Looking, he hadn’t worked — much less goofed around — in a studio in years, so it was only natural that the album felt stiff. Years ago Gucci famously freestyled the entirety of No Pad, No Pen; now, he was posting lyric sheets to social media. In this new, more deliberate incarnation of his writing style, his metaphors got a little less random, his flows slower and less winding. After giving so much away for free, he’s certainly entitled to capitalize on his fame. But it’s hard to shake a sense that, in hopping right into a post-prison album rather than releasing a more structurally loose and arguably lower-pressure mixtape, he was caught playing catch-up to his younger peers.

But fuck it. Albums in 2016 matter because they matter to Gucci Mane. I’m happy to set aside my complaints that his initial return lagged behind his looser 2000s mixtapes — and some of the music he’s released since, like his more playful East Atlanta Santa — because of this fact: in reaching No. 2 on Billboard, Everybody Looking became the highest-charting Gucci full-length to date. A few months later, another album-released Mike WiLL production would take him even higher: “Black Beatles,” the Rae Sremmurd song on which Gucci Mane features, became his first No. 1. He earned it. — DUNCAN COOPER