It’s drizzling in Philadelphia, and Cleo Tucker really wishes they weren’t holding a pumpkin. It’s a big one, too, with a freakishly long stem that’s curved like a question mark. They bought it impulsively off the street, not really considering that it meant they’d have to lug it around while we walked. Arms tired, they hand it off to Harmony Tividad, their best friend and bandmate.

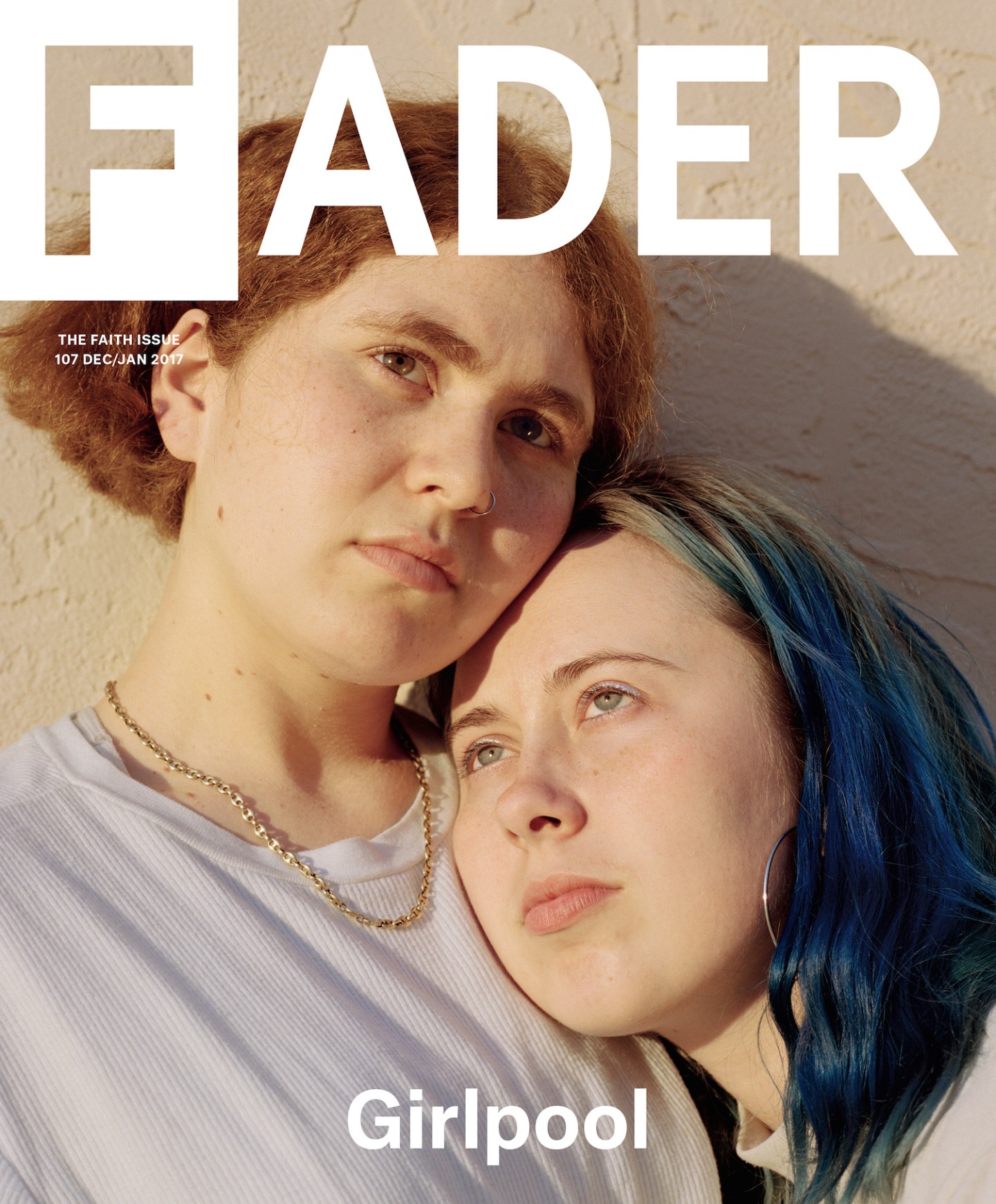

“I feel like I’m in a bad Charlie Brown episode,” Harmony says, yellow leaves crunching under her paint-speckled Chelsea boots. Harmony turned 21 in September. Her nose turns up slightly at its tip, and her uncombed hair is roughly four different shades of blue — complementary to 20-year-old Cleo’s, which is wavy and orange, just a few shades darker than their pumpkin.

We’re walking to Harmony’s house on the other side of Kensington, a neighborhood in North Philadelphia. To escape the rain, we duck inside Resource Exchange, a second-hand craft store that Harmony likes to visit. She leaves the pumpkin by the door. Inside is a mess of art supplies and knick-knacks, and the pair are interested in pretty much all of it, screaming across the store for each other when they pick up anything particularly cool. At one point, seemingly unprovoked, they start singing a James Taylor song in unison: “You just call out my name, and you know, wherever I am, I’ll come running…”

Since high school, Harmony and Cleo have been making melodic punk in the simplest terms. As Girlpool, their music is dependent on their connection, which sometimes teeters on supernatural, and their youthful curiosity about the world they inhabit together. Their first full-length album, last year’s Before the World Was Big, won them lots of young fans within punk and DIY rock circles, resonating with the sort of sad and hopeful kids who appreciate raw emotion more than just about anything. They performed its songs as a pair, without drums — only bass, guitar, and their chills-inducing harmonies.

Several weeks before my trip to Philly, Harmony and Cleo finished recording their second full-length record. Called Powerplant, the album features a full-band sound, drums and everything. It feels like a big moment for the duo, who have seen a lot change since starting the band as teenagers. But their relationship has remained a constant, a nice reminder that not every great love story is a romantic one. Girlpool is a testament to things that will always feel important, like true friendship, and the way rock music brings people together.

Cleo and Harmony are both from Los Angeles, and though they didn’t meet until they were teenagers, you can imagine they would have clicked as kids. Harmony grew up in Hollywood. “I’m a California girl,” she says, suggesting that she’ll definitely return to the West Coast if she ever raises children. Her mother, an “intuitive healer” who often works with people in the entertainment industry, chose the name Harmony after meeting a woman with that name, in a dream. Her father, a session bassist, would always play music in the car, regularly quizzing her about types of rhythms and which instruments she heard.

Harmony always loved to sing, and choir was a constant as she bounced around L.A.’s network of performing arts magnet schools. “I had friends, but I wasn’t cool,” she remembers. “I would go to parties and pretend to get drunk and write poems on my phone in the corner because I felt weird all the time. It’s so cliché and dumb, but that’s what it was like.”

Cleo grew up creative, too. She was raised in a pretty Westside neighborhood called Rancho Park and got her first guitar at age 7, after seeing British singer-songwriter Joan Armatrading perform at a Borders bookstore. “I was in such awe — I had never seen a person play the acoustic guitar so beautifully,” she tells me. Her mother, a visual artist with dreadlocks, and her father, a lawyer, sent her to study at New Roads, a forward-thinking day school in Santa Monica where Cleo played in the jazz band, though she was more interested in covering rock songs.

Cleo loved artists like Neil Young and Elliott Smith and Conor Oberst, the tortured 2000s emo singer. Her favorite Bright Eyes song was “Land Locked Blues,” a world-weary duet between Oberst and Emmylou Harris. They sing his disillusioned poetry in unison, nice and slow: “And the world’s got me dizzy again/ You’d think after 22 years I’d be used to the spin.” It’s a heartbreaking rock song about being young but feeling old, the kind that might make you see the world a little differently. It didn’t take Cleo long to figure out she could write songs like that.

When they were old enough to drive, Harmony and Cleo started going to shows around the city. They first met in 2012 at The Smell, a punk venue right next to Skid Row. Harmony was working the door and DJing doo-wop between sets. The all-ages space is a DIY institution, probably best known for hosting noisy rock bands in the late-aughts, like Health and Vivian Girls and No Age. That night, it was a twee-punk band called Moses Campbell. Cleo showed up in a group, and Harmony felt drawn to her presence straight away. “I just thought she was so free,” Harmony remembers. “She was dancing and laughing really loud and causing a ruckus. She just didn’t care.”

In the months that followed, Harmony and Cleo began hanging around in the same crew. They started a band called Dearest with three other friends; everyone wrote their own songs, which the rest of the group would learn and support. Somewhat impulsively, Harmony and Cleo decided to try and work on music on the side, as a duo. “We sort of realized that we had super similar tastes and writing styles and intention,” Cleo explains. “One day we were like, ‘Let’s just do it. Let’s just have no one else. It doesn’t matter. We don’t need a band. We’ll just both play guitar.’” Cleo says writing together felt preternaturally comfortable, and the songs came out of them in a way that neither had experienced before. “Before Girlpool, we would try to make songs that we thought were ‘good,’ or whatever,” Harmony says. “But when we talked about Girlpool, it came from a place of wanting to be as sincere as possible. We wanted to make something that was transparent and real to both of us. We just wanted to be ourselves.”

They named themselves Girlpool after a bleak chapter in Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, about secretaries working in the basement of a laboratory, obliviously typing information being fed to them from the outside. Their first songs, which would be hastily assembled onto a self-titled cassette, were innocent but not at all oblivious, recalling the after-school angst of early riot grrrl. “Slutmouth” questions gender roles, and on “American Beauty,” they shout about oral sex without flinching. The hook of “Jane,” a half-sung saloon ballad about a girl standing up for herself, is just Harmony’s high-pitched scream. “Plants and Worms” is an existential nursery rhyme about moving away from home. “I’m uncomfortable looking in the mirror/ Seeing that my skin is clearer,” they sing, their voices coexisting in an imperfect union.

When Girlpool started playing around L.A., they were embraced as local favorites pretty much immediately. Harmony and Cleo credit their hometown success to the fact that they had an established place in the scene; they already had friends to book them gigs and others to sing along at shows. But the attention was thanks to something else, too: they were really fucking good.

Still, they were just kids who lived with their parents, and weren’t quite ready to be professionals. While Cleo finished up high school at New Roads, Harmony took classes at a local college and made extra cash delivering flowers. Cleo, who once cut Spanish class to perform at the L.A. Art Book Fair, made tentative plans to attend Hampshire, the hyper-liberal college in Western Massachusetts that Elliott Smith graduated from in 1991. She wasn’t ready to stop playing Girlpool shows, so she deferred for a year. “I kind of envisioned playing that year, then going to college and being really sad that I didn’t get to continue playing music with my best friend.”

But everything changed when Wichita, the British indie label that released the first Bright Eyes album in the U.K., offered to re-release their self-titled EP and put out their debut full-length. “We didn’t think that would ever happen,” Cleo remembers. It wasn’t the only sign that they were doing things right: Jenny Lewis, the singer-songwriter and ex-frontwoman of turn-of-the-century rock group Rilo Kiley, became a fan and invited them to open a few of her tour dates. Six months after starting Girlpool, they played in front of a sold-out crowd at Manhattan’s Terminal 5, a 3,000 capacity venue. They started touring more. “We were just in a car for 10 hours a day sitting next to each other, talking and talking and talking,” Cleo remembers.

“I wish that I could hold back my personhood more, but it’s hard to not fully exist. Or whatever.”—Harmony Tividad

The songs they wrote for Before the World Was Big mirror the slower moments on their first EP: sparse and thoughtful and primarily concerned with the visceral experiences of getting older. They were recorded with help from Kyle Gilbride of the band Swearin’ in early 2015, just after Harmony and Cleo packed up and moved across the country to Philadelphia. “Their dynamic is very interesting — it’s not like any other band that I’ve recorded,” Gilbride told me during an interview in February 2015, shortly after finishing work on the album. “They read each other for timing and take completely irregular pauses and just sort of ebb and flow through the songs. They communicate really well and they compromise a lot. Their musical sensibilities are different, but they have this common script.”

Girlpool’s music shares certain traits with songs by loopy anti-folk storytellers like Kimya Dawson and the loose-screw romantics from the golden age of K Records, the Olympia indie label founded in 1982 by Beat Happening’s Calvin Johnson. A lot of that music featured rudimentary structures and, though it was often made by people in their twenties or thirties, celebrated a sort of perpetual teenageness: sweaty palms, schoolyard crushes, an unhealthy longing for the picturesque. Beat Happening’s messy playing was something of a punk statement, cutesy in aesthetic but confrontational in practice. Girlpool’s first album, made by actual teenagers, felt different. The music was simple both because they were still learning how to write, and because they wanted their feelings to come across clearly; the confrontational part was how unbelievably honest it felt.

Girlpool’s style fit in with a handful of other young DIY bands that were gaining momentum in the contemporary underground, like Alex G, the brilliant rock songwriter from Pennsylvania, or Frankie Cosmos, whose Bandcamp page contains hundreds of sweetly sad pop songs about her life in New York. “The way Harmony and Cleo see the world and the realness they hold on to through any situation is amazing to be around,” says Greta Kline, the songwriter behind Frankie Cosmos. “I think the similarity in all our approaches to art is this goal of staying true to ourselves — presenting your reality without gloss or shame, and looking at the world and taking stuff in through that lens.”

Lots of times Girlpool’s lyrics are equal parts deep and disposable, like a middle-of-the-night phone call between friends. (“I’m still looking for sureness in the way I say my name/ I am nervous for tomorrow and today,” they sing on “Chinatown.”) But just because a feeling or thought is fleeting, does that make it any less perfect? Harmony and Cleo discussed every line, sometimes for hours. “Having another person to bounce ideas off allowed us to consider more closely how we see the world in a critical way,” Harmony says, reflecting on their early writing sessions. “That helped us find our voice.”

Harmony’s car is a cherry red Volvo from the early ’90s. She’s short, so she leans forward in the seat when she’s driving. Cleo has decided she wants to make a pie out of their pumpkin, so we’re going to Trader Joe’s for the ingredients. At stoplights and stop signs, Harmony texts. She’s working on getting all her friends over to her place later, to talk and drink and eat homemade pie. Her pal Greg is already here, smoking a cigarette in the backseat. He’s got on a light denim jacket, a leopard-print undershirt, and a stoned-looking smile. He just got fired from his job at a vintage clothing store, so he’s down to hang. Harmony and Greg are a pretty spectacular duo in their own right, more like platonic partners in mischief than just plain friends.

“Sweet Shine” by Sonic Youth is playing, and Cleo has Kim Gordon’s innuendo-filled lyrics pulled up on her iPhone, following along. Harmony slows down on a side street to watch some guys painting the exterior of a residential building. “That’s amazing,” she says, though it’s not clear exactly what she’s talking about: the maroon paint, or the architecture of the house, or just the act of taking something plain and making it beautiful.

“What was it you said about love, Greg?” Harmony asks, searching for him in the rearview mirror. She has a little bit of metallic eyeshadow on, which glitters silver in the reflection.

“What was it?” he says. “Oh yeah — romance is holding hands and walking on the beach for a little bit too long.” Harmony lets out a loud laugh that’s actually more of a cackle.

“I love romance,” Cleo says, to no one in particular.

Back at Harmony’s place, a three-story house with warped wood floors and paisley print couches, Cleo glides around the living room on a red Razor scooter. It’s a sweet reminder that this is Philadelphia, where the cost of living isn’t too bad, and where having enough space to ride a scooter inside isn’t all that rare. After moving to Philly as a pair, Cleo and Harmony both relocated to Brooklyn in early 2016, where they already had friends in the borough’s underground music community. Harmony decided she wasn’t suited for New York and moved back to Philadelphia in June. Cleo, who lives with roommates in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn, stuck around. “In New York, people work hard and play hard,” Cleo tells me. “In Philly people just party hard.”

Greg, maybe half-jokingly, suggests moving the table so that when people come over there’s even more room to dance. At one point, Cleo sneaks upstairs to record a bass part for the cover of “Linger” by The Cranberries that she and Harmony have been working on. “I’m gonna do a handstand,” Harmony says, and then she does one.

On rare occasions, Cleo and Harmony’s personalities will clash. “Cleo tires, and I don’t tire,” Harmony explains. This past summer, for example, on the day before Girlpool was supposed to play Coachella, Harmony hopped in a van with Sheer Mag, a punk band from Philadelphia that was also playing the fest. She thought they were heading to Indio, the desert town where Coachella is held, but they actually drove to Joshua Tree. Harmony didn’t realize until it was too late, leaving Cleo stranded without proper accreditation to load in until she made her way back. “I was so mad at Harmony that day,” Cleo says, laughing. “I had to sneak into Coachella … to play it.”

But their conflicts never last too long. “I don’t think we’ve ever yelled,” Harmony says. “We have had periods of feeling like we can’t connect or communicate in a certain way, but I don’t think either of us ever doubts that we love each other.”

After a while, friends congregate in the backyard, sitting on mismatched patio chairs and plastic milk crates. Matt Palmer, who plays guitar in Sheer Mag, is here too. He and Harmony reminisce about the Coachella mishap and some other debauched misadventures while a Three 6 Mafia song plays from an iPhone. At one point, about half the group goes into the kitchen to do shots. Cleo is on her phone in the living room, texting her girlfriend Emily Yacina, a Pennsylvania-born singer who’s been collaborating with Alex G since high school and is a talented songwriter in her own right. There’s only one shot glass, so everyone takes a turn, and makes a toast to the group. Harmony, cheeks rosy, is up first. “I hope, someday, things in my life make sense,” she says, before throwing her head back.

“I used to romanticize, What if I wasn’t trying to figure it all out in a car, in a parking lot, like an hour before we play?”—Cleo Tucker

The next morning, we’re in Harmony’s living room again. Somehow, she’s been up for hours. Last night’s mess of beer bottles and pie crumbs has been cleaned up, and she says she already rode her bike to drop off a roll of film at the camera store. Cleo, who drank much less, slept in.

Over coffee, we all talk about their new album, which they recorded in Los Angeles over the summer. They had loose plans to record it in Chicago with Jeff Tweedy, the frontman of Wilco, one of America’s most beloved rock bands, but due to scheduling conflicts, they did it themselves, with some key assists from drummer Miles Wintner and their friend Drew Fischer, who helped them record a 7-inch once. “We were gonna go to L.A. to practice with the people we wanted to play on the record,” Cleo remembers. “And then we got there and we were like — we have a finished album, we have three weeks to be here, but we would wait four months to record in Chicago and we’d have to fly out the people to play on it. Let’s just make the record now.” While they’d really love to work with Tweedy in the future, they’re happy with how everything unfolded. “It was honestly really amazing how it all worked out,” Harmony added.

The drums first kick in 50 seconds into “123,” the album’s jaw-dropping opener. It starts whispery and then just explodes, a real Wizard of Oz technicolor moment. Powerplant’s atmosphere is meticulously considered, all vivid hooks and controlled bursts of noise, but the Girlpool magic remains; it’s full of private thoughts meant for singing along with. “I’m watching from bodegas on that street/ and I’ll say barely just how highly I can think,” Harmony sings over blurry guitars on “It Gets More Blue,” an ultra-catchy standout from the album’s second half. While every track on Before the World Was Big was written together, this one is partially the result of solitary writing. This happened naturally, because they had been living apart, but it could also be because Harmony and Cleo trust and understand each other in an even deeper way than before.

Powerplant will probably come out next year. They’re no longer working with Wichita, so they have to settle on a new label to sign with before the record comes out. A bunch have shown interest, but they want to make sure they make a decision that feels right. “Relying on other people is frustrating,” Cleo says. “When we were younger, we were really young, and that was a point of territory that some people navigated inappropriately.”

I ask them what they want out of a label, and Cleo scrunches up her face: “I don’t know. What do you want, Har?” Harmony’s brain works quickly, and she rarely has trouble saying what she means, or what she thinks she means, in any given moment. She offers a simple answer: “Not to be told what to do.”

That faith in their own instincts extends to all of the public-facing aspects of Girlpool. Some of the other bands in their world are more wary of press, or have a hard time with it, but being open in interviews like this one feels like another extension of Girlpool’s overarching goal: to be themselves no matter what. “I wanna play music forever, and if I wanna do that, I have to have some sort of openness to the fact that I’m putting my emotions on the line,” Harmony says. “I have a hard time stopping myself from being myself, like, at any point. In certain moments, I wish that I could hold back my personhood more, but it’s hard to not fully exist,” she says. “Or whatever.”

On Powerplant, Harmony and Cleo were concerned with accessibility, but they also just wanted to make a really good album. It’s 28 minutes, so every bewildering riff and bass pluck counts. These are 12 songs that mean a lot to the women who made them, and as a listener, Cleo and Harmony never feel out of reach. A lot of DIY rock is like that, and that’s part of what makes it so inspiring. “Projects that embody the creative person completely encourage those who listen to do the same thing, even if the listener initially just mimics the artist,” Harmony says, talking about her peers, like Alex and Greta. But the idea applies to Girlpool, too.

“Cleo and Harmony are symbols of the rawness and honesty that our entire society lacks,” Willow Smith, the 16-year-old daughter of Will and Jada Pinkett-Smith, tells me in an email. Willow is a well-documented free thinker and Girlpool fan, and her thoughts on the band reflect that soul-searching, too. She appreciates the way Girlpool’s music is about being yourself, even when it’s not convenient. “They represent a way of being that this generation identifies with on a spiritual and subconscious level. Freeing yourself from ideologies that suffocate your innermost self has always been, and will always be, the wave.”

It’s no secret that rock & roll is not the dominant American music genre it used to be, even compared to the 2000s heyday of bands like Bright Eyes and Rilo Kiley. But the need for the kind of truthful, underground music that Harmony and Cleo make never really goes away, and you can see that style’s fingerprints on some of 2016’s most talked-about moments, which also felt hinged on earnestness. For one, Frank Ocean recruited Alex G to play guitar parts on his two 2016 albums, Endless and Blonde. On the latter’s most existentially angsty song, Ocean also prominently interpolates an Elliott Smith lyric.

There’s an argument that sometimes comes up against what some would consider a “nostalgic” rock sound: Why would I listen to these new homemade rock songs when I could listen to older ones that sound pretty similar? But passionate young music fanatics don’t necessarily think that way. This is their time and these are their bands. They feel lucky when they see them perform live, and proud when those groups score an opening spot on a big tour or an unexpected slot on the Coachella lineup. To Girlpool fans, the golden age of indie rock is happening right now.

For Harmony and Cleo, making music together has become a full-on lifestyle, a shift that they’re still trying to figure out how to navigate. “I just don’t want to put any energy into being anywhere but, like, moving forward,” Harmony says. After their first album’s hectic touring slowed down, Cleo got a barista job in Manhattan and toyed with the idea of enrolling in art school. “I was feeling very aimless, you know?” she says. “Perspective was getting confusing, because I was waking up and not doing anything, but had more than enough money to pay rent. It was like, This is weird. This shouldn’t be right.”

Growing up and moving out can feel disorienting, even without the added instability that comes with being on the road a lot. “I feel like, for me, that prompted a lot of what we ended up writing about,” Harmony says of the new record. “Looking for an anchor and feeling like you’re looking in all the wrong places.” Luckily for Girlpool, there is at least one stabilizing presence: each other.

I ask Cleo if it’s been hard to reckon with the pressures of adulthood while being in a popular band. “I used to romanticize, What if I wasn’t trying to figure it all out in a car, in a parking lot, like an hour before we play? But, whatever.” She pauses for a second. “I’m trying to stop saying ‘whatever.’ That’s something I’ve been trying to stop for a year.”

“You do say it a lot,” Harmony says. Cleo nods. “I think that would be good for me to work on.”

Several hours and drinks later, at a house in South Philly, Harmony and Cleo sip on Golden Monkey, an abnormally high alcohol-by-volume Belgian beer. It’s the end of someone’s birthday party; streamers sag, floor balloons kick around. They’re both beat, so they pack up and wait for an Uber in the living room, slouched on a couch while rowdier guests DJ off a MacBook. Someone puts on “Mr. Brightside” and they both stand up with a jolt. The song was a huge hit for The Killers in early-’00s, taking up residency on rock radio and inside Discmans across the country. Girlpool’s songs might never be that ubiquitous, but it’s very much the kind of music you can imagine losing your shit over years from now, the first notes of a simple guitar melody triggering a rush of bittersweet memories.

At the party, Harmony and Cleo start playfully moshing to “Mr. Brightside,” like it was a hardcore punk song. Cleo stomps around, tugging the drawstrings on her sweatshirt’s hood until you can only see her mouth. Harmony breaks into an air guitar solo, her oversized hoop earrings swaying from side to side. Cleo grabs her by the shoulders and they both shout every lyric, word for word.