Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Solange loves to zoom. For months, she’s deployed the technique on Instagram and Snapchat, using her iPhone camera to magnify something in the frame or, conversely, to pointedly pull back and place said thing in the context of its surroundings. On her always-whimsical, often-symmetrical Snapchat, the singer regularly closes in on body parts, buildings, plants, the faces of friends and family. In a video posted to Instagram in May, her target is a bright blue dress that’s in consideration for the Met Ball: standing in front of a mirror, she uses two fingers to pinch her screen until she gets closer and closer to the cobalt layers in her reflection, cropping out her face, most of her body, and everyone in the background. In one Snap from June, she cuts awkwardly through a beautiful veranda and into the unsuspecting faces of her older sister Beyoncé and Shiona Turini, a friend and frequent style collaborator. Both women, by now familiar with Solange’s routine, blurt out in tandem, “Wait, are you zooming now?”

The zooming also figures prominently in the videos for “Cranes In The Sky” and “Don’t Touch My Hair,” which Solange released this week as visual companions to A Seat at the Table, her fourth album and third full-length. Solange directed both videos with her filmmaker husband Alan Ferguson; together, they created a pair of living tableaus, more concerned with telling stories through texture than traditional narrative. Here, more so than on social media, where zooming can be cute and irreverent, the effect feels strong and deliberate. It’s a stylistic device often avoided by directors for a handful of reasons: a camera zoom comes with technical limitations; it rarely adds as much to a scene as, say, a pan does; it can create an overly dramatic, borderline-creepy effect, as mastered by Quentin Tarantino in films like Kill Bill Vol. 1 and 2 and Inglourious Basterds. That pointed drama, I suspect, is part of what attracts Solange to it. Beyoncé suggests as much in another Snap from that same week in June; in the short video, the sisters are reflected in the shiny metal of a Liaison plane and Beyoncé, laughing, asks, “What about your zoom? Your uncomfortable zoom?”

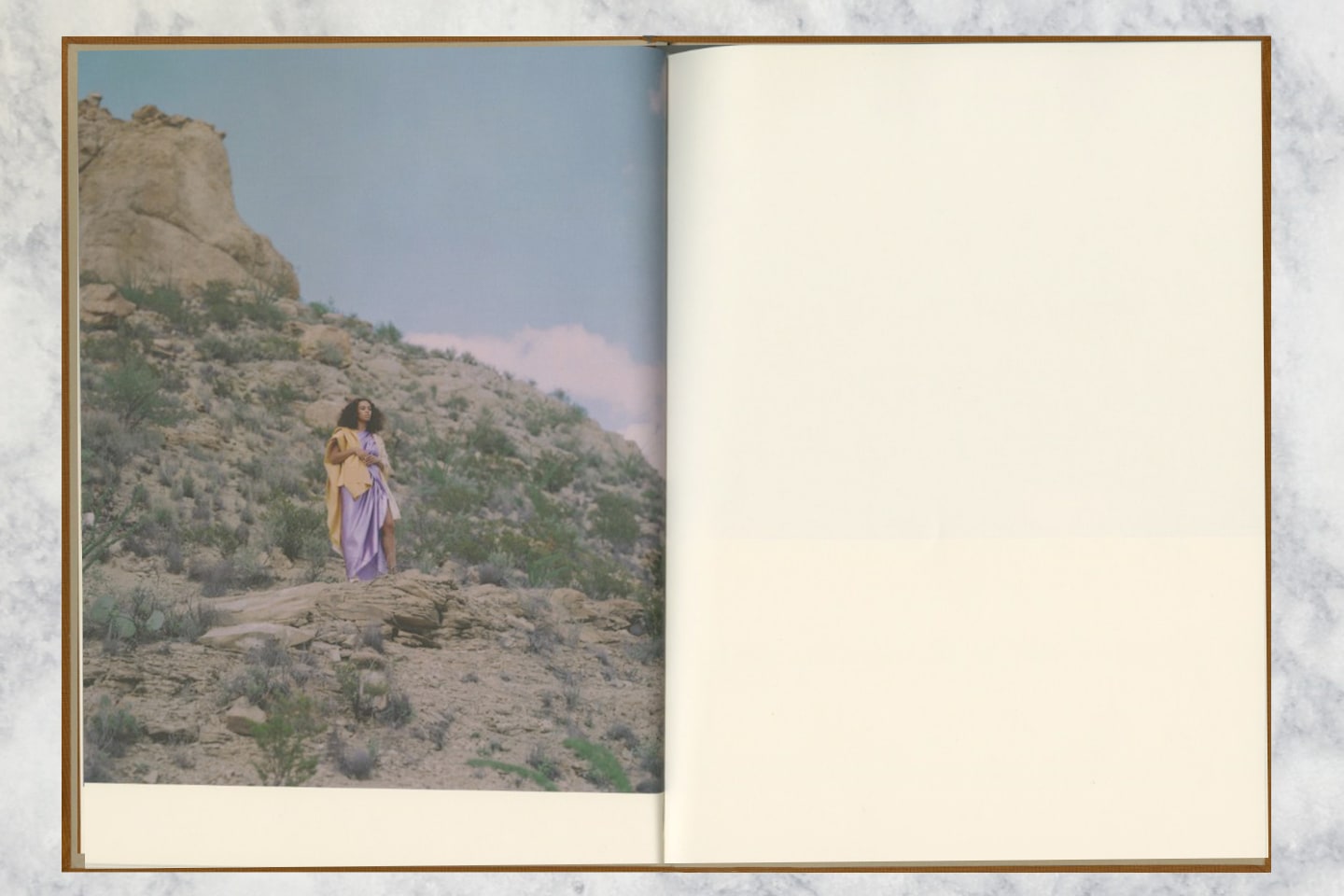

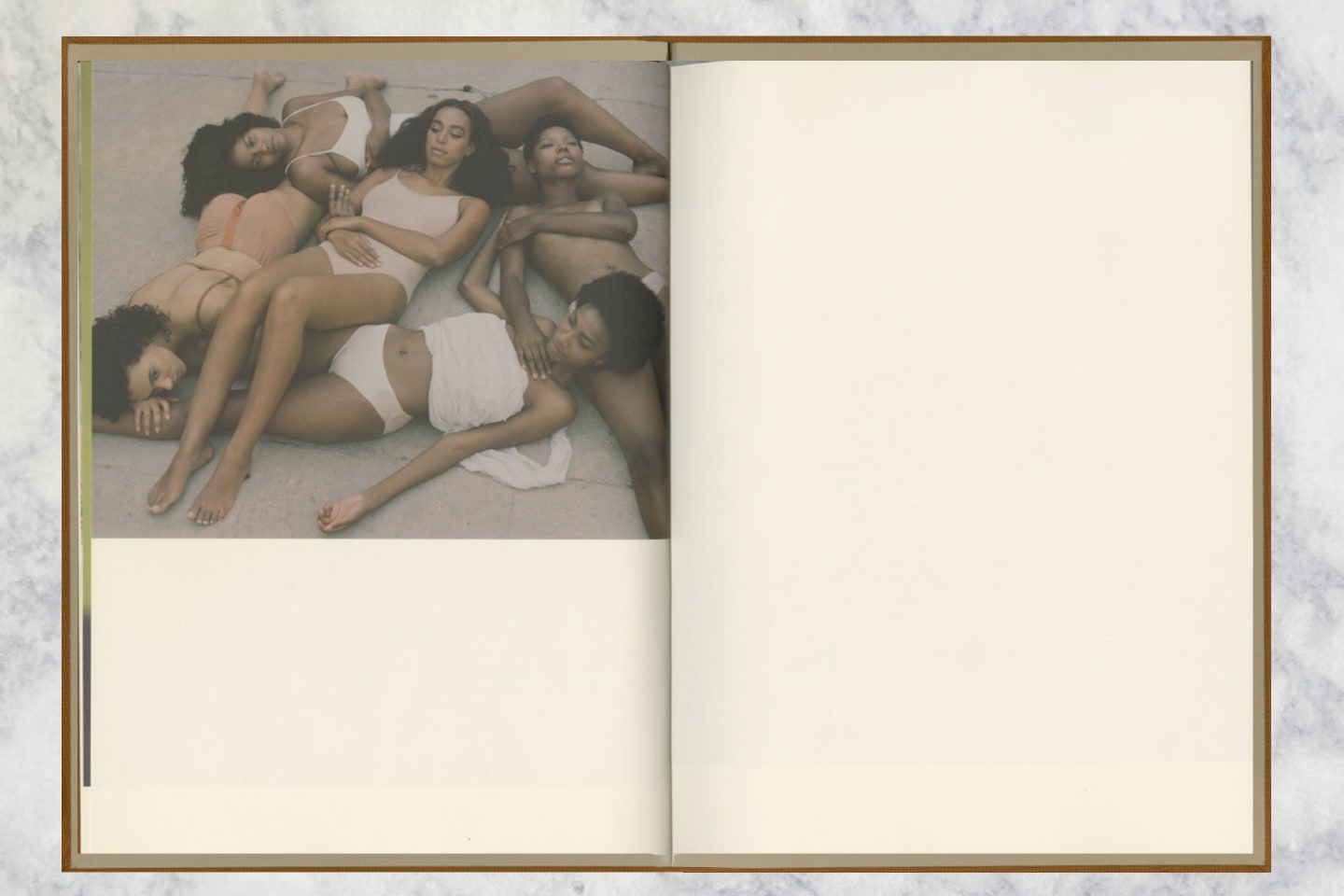

In one particularly beautiful “Cranes” scene, Solange is all angles, her brown skin and satin, millennial-purple dress contrasting against a background the plush red of theater seats; when the camera pulls away, it reveals her swaying alone, small, in the middle of a large, almost-ghostly interior. When it zooms back in, moments later, the world beyond her falls away, as if only Solange exists. It’s uncomfortable, but effective. In another scene, she’s standing in a gold-fringed dress, framed by the vastness of a desert-rock expanse behind her. When the camera draws back, she appears to have nearly disappeared — a small, glowing orb dancing on a mountain much bigger than her. In the brilliant closing scene of “Don’t Touch My Hair,” she zooms to opposite effect. The camera slowly approaches her spastic choreography, highlighting Solange as a single body surrounded, as if protected, by dozens of anonymous black people dressed in all-white. Across A Seat at the Table, too, Solange frames herself both as individual (it’s fitting that she’s known to so many as Solo) and as just a member of various concentric communities that grow outwards, stretching back into her family’s past and into a nameless black future.

Those communities, both real and imagined, are very present on the album: her parents contribute stories through interludes, a circle of artist-friends support her vision with production and vocals, and black people everywhere are directly addressed, both spoken to and for. Throughout the 21-track project, a collective “we” is invoked, with kindness and tenderness. But alongside that “we” is a powerful, distinctly unique “I.” As much as A Seat at the Table is an album about black empowerment and black womanhood — and it is, as she herself has explained and others have interpreted — it’s also an album specific to Solange: mother of Julez, wife of Alan, sister of Beyoncé, daughter of Tina and Matthew. How she connects the many facets of that complex identity to the various worlds beyond her is at the project’s core. In some ways, it’s a conceptual zoom-out that pulls together the politics she’s formed and the aesthetic she’s curated during the four-year process of its recording, with the sustained anti-racism in places like New Orleans and Los Angeles, where pieces of the album took shape.

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Throughout the 21-track project, a collective “we” is invoked, with kindness and tenderness. But alongside that “we” is a powerful, distinctly unique “I.”

In much of the press and social media updates surrounding A Seat at the Table, Solange has stressed the personal and artistic significance she found in tracing her family history: she interrogated her parents on their own experiences with racism and their parents’, she moved to her ancestral Louisiana for clarity and peace of mind, and she traveled even further, to South Africa and Rwanda and Senegal, to find ease for herself and her son. As Solange explained in a conversation published on her Saint Heron website, “A huge part of me moving to Louisiana was to really have a moment of self-reflection and self-discovery. I’m a strong believer that in order to know where you’re going, you have to know where you came from. I think that I chose New Iberia based on that area being the start of everything within our family’s lineage.” In an interview with The FADER, she said of spending time in Africa: “[I]t's who I am and it's where I came from. I love feeling connected to that, it has helped me to understand myself more.”

To go along with the generational self-discovery, however, it seems that Solange also spent time considering the arc of her career thus far and looking back on the three decades’ worth of milestones that delivered her to this moment. An Instagram caption celebrating her 30th birthday this summer functions sort of like a zoom-out summing up much of her life thus far. In between important personal touchstones, she maps out the makings of her as an artist: “Wrote first song (A jingle for the United Way)” at age 9; “Wrote/Released my first album for weird teenagers” at age 15; “Wrote/released third album” at age 26; “Started writing most proud of body of work” at age 27; and “Completed 4th album” 72 hours before turning 30. All along Solange’s public path to self-discovery, media and industry forces seemed intent on delegitimizing her. When she released both her first and second albums, she was simply written off as Beyoncé’s little sister, a product of nepotism. When she re-emerged soon after and demonstrated an interest in the indie rock bands of the early aughts — befriending Grizzly Bear, collaborating with Of Montreal, and covering Dirty Projectors — she was described as inauthentic. When she delivered astute criticisms of music journalism’s failures in covering contemporary R&B, she was alternately painted as ungrateful and overly sensitive. Until she found a home and community for her sound with 2012’s True EP, the songs she’d written for herself and others, and her curatorial work in art and music, played second fiddle.

Tellingly, the website that accompanies A Seat at the Table is host to what is effectively a resumé, listing her albums, credits, collaborations, and artworks past. She’s been working this whole time, it seems to say, to arrive at something that is the sum of its parts. Intentionally or not, it also directly addresses some of the obstacles she’s faced as an artist for years — the gold lamé, pop-star shadow cast by her sister; the unfair, racialized assumptions that undermined her evolving tastes in music, style, and art; the equally unfair, gendered narrative that gave men collaborators like Dev Hynes undue credit for her work. As she uses A Seat at the Table to zoom out and define her place in a world as a black woman, she’s also using it to zoom in and create a version of herself in an industry that has long tried to dictate it for her.