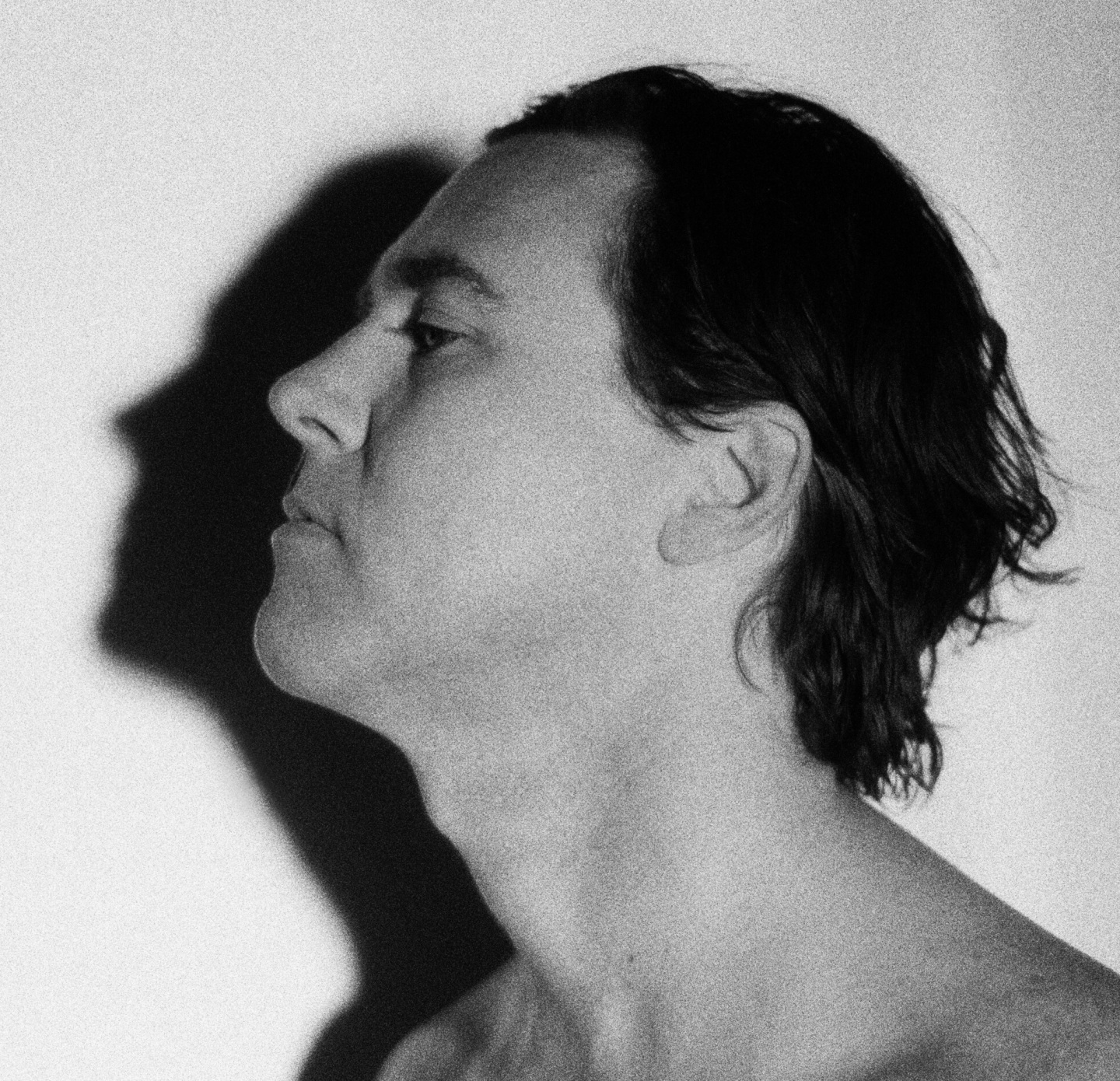

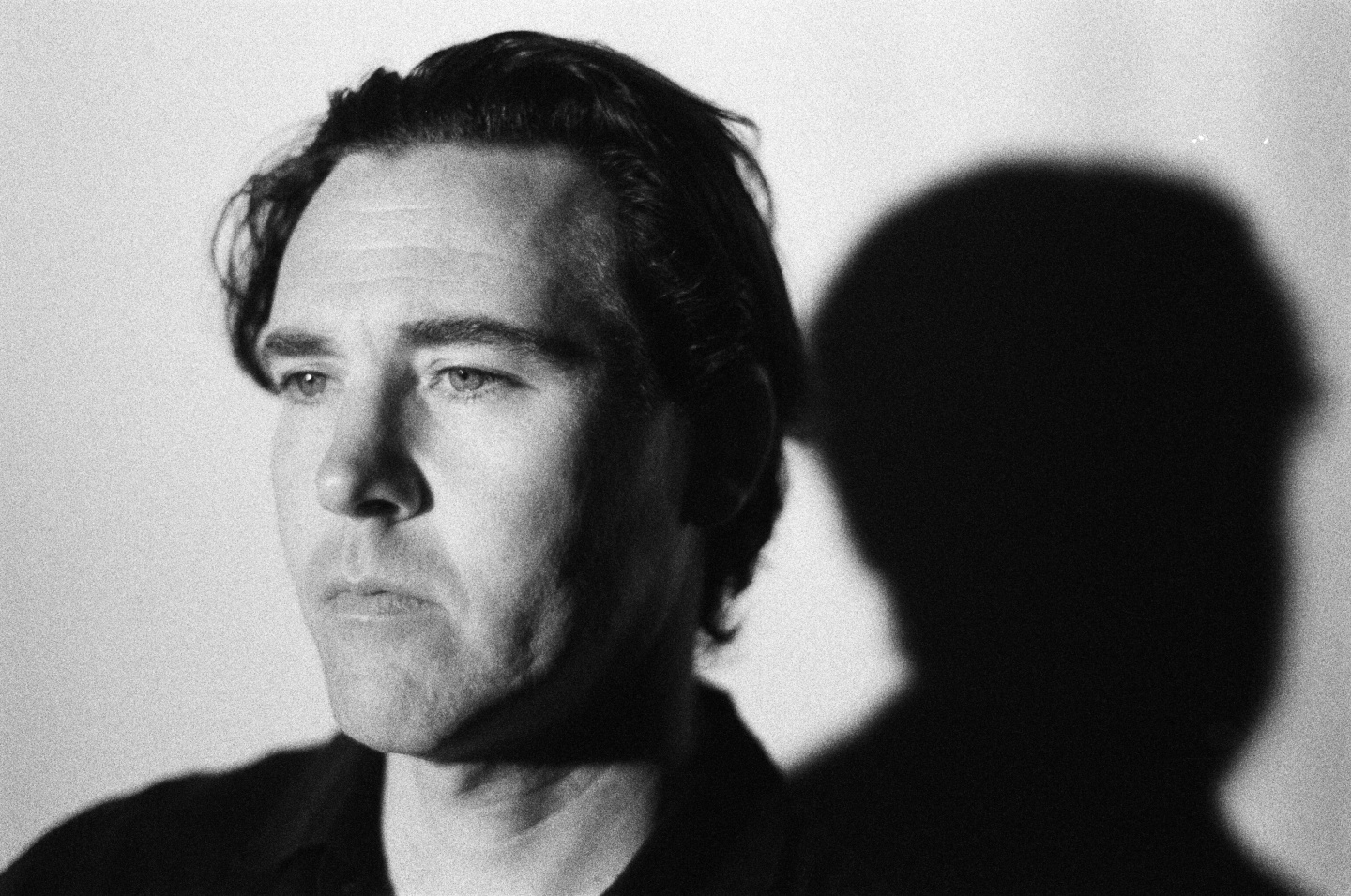

Rachael Pony Cassells

Rachael Pony Cassells

At 38 years old, and with the release this week of his eighth full-length album, Mangy Love, Cass McCombs has long cemented his reputation as “one of our generation’s most important songwriters,” as Grizzly Bear’s Chris Taylor called him in a recent roundup of praise from peers. On Mangy Love, he is at the height of his talents, marrying some of the straight-up prettiest tunes he’s ever recorded with the sort of consistently provocative politics he’s always been known for.

McCombs also has a reputation for not talking much. So when I got the chance to speak to him for an hour on the phone this week, I jumped at the chance. Here is that conversation, condensed only slightly, and ranging wide from phony jam bands to Chelsea Manning and the nature of time.

People who write about your music often say you don’t like to talk about yourself, or your own biography. Is that overblown?

It definitely gets overblown. I'm cool with talking about certain things about myself, but the priority is ideas. And I think an interview, conversation, whatever, is good place to continue to create. That's why I'd rather just talk about ideas. Perhaps biography comes woven in and out of these ideas, but idly talking about biographies just seems wack. It just seems wack, you know. And no one wants to hear solely about someone’s life. Maybe someone’s experience in context of an idea…

Another common topic is your traveling lifestyle: living out of a car or staying with friends, avoiding material possessions. At the same time, you recently talked about having a big record collection and being a Beatles completist.

I've always been a weird collector of things, always, since I was a kid: stamp collections, baseball card collections. Even trash, bottle caps — I had a bottle cap collection when I was a kid. There’s just something about collecting things, and looking at your collection all together and seeing what they have in common and what makes each object unique I find interesting. I also don't think that's in any kind contradiction with living in an ascetic kind of existence. I think maybe we tend to generalize people as being one or the other. But I think all of us are both, we're a little bit of both. I just don't believe in these fake-ass archetypes. "This is the wanderer with no possessions. This is the billionaire businessman with women on each of his arms.” It’s just horse shit. We're all way more nuanced — we’re dynamic and we change constantly. I've slept on the street, lived out of my car. They're both real.

I know you spent a few weeks in Ireland recently. What brought you there?

I’ve been out there a few times and made friends with a few musicians. I'm really interested in Irish music, and the music of the British Isles: Wales, Scottish, British music. Some of the early songs I learned were Scottish and Irish ballads and things like that. As I grew up, I started to see that a lot of the bluegrass and American folk music directly comes out of that tradition of balladry. Also the style of flat-picking and fiddle playing is a direct linage.

I was one of those kids who it was instilled on me early on, as a guitar player, like, "Oh, you wanna be a rock & roll star, huh, kid? Well rock & roll comes from the blues — that's slavery, sharecropping, that's Jim Crow. You gotta come correct. This is not glamour. This is pain and suffering, and expression, and release, and joy.” And I feel that Irish music and culture, coming out of a thousand years of genocide, basically, is also a beautiful response to that… But I don't know if that's being transferred to the new generation anymore. I think millennials only want to listen to millennial music; they don't even care about something that doesn't resemble them in the mirror.

Did any of that Irish music influence the new album?

I was afraid to even mention Ireland at all because I didn't want people to think I went on a fucking vacation. [Laughs] I'm anti-tourism. I wrote a song on my second record called "Tourist Woman," out of a conversation we were having with the band about how tourism is the modern colonialism. We obliterate local cultures, local economies, and make them completely dependent on our bourgeois demands. It's really fucked up and it's gotta stop. I went to Ireland to learn about the struggles and the history of the people of Ireland, to learn their songs and to bring them back to the States, to sing them to the people here. I didn't sing any of them on Mangy Love, so it doesn't really matter.

“There’s a lot of people trying to co-op shit for a buck, and I take offense to that. There’s a lot of funniness going on, where people fronting to something they ain’t.”

I read there were 21 musicians playing on Mangy Love. Is that right?

Yeah, that sounds plausible. It’s a family thing — a big family of musicians, brotherhood and sisterhood of music.

That comes through. There’s a real jammy vibe to the record.

I would also say this "jamming" idea is another thing that is misunderstood by people who aren't in that world. There's a lot of fake heads out here, but that's my culture. That's my family. I've been doing this — this is all I've been doing since I learned how to play guitar. Yeah, there's a lot of people trying to co-op that shit for a buck, and I take offense to that. There's a lot of funniness going on, where people fronting to something they ain't. Naturally, I want to be protective of my culture. One thing I learned about jamming is that it's such a vague idea for musicians. A lot of what's called "jamming" isn't even improvisational anymore. The actual experimental improvisational elements have been scaled down because it's not inlined with capitalism.

But it's fun as hell. The style that I gravitate toward is a Northern California style of jam. Not just the Grateful Dead, but also Haight-Ashbury and that whole historical movement, from The Charlatans all the way down. In Germany, there's a whole other style. Electronic music, there's a whole other style. Of course, country music has improvisation and jazz as well. I think these ideologies actually prove to enhance each other, when these worlds collide. Different people from different walks in life come together. That's why I ain't gonna front like I'm German. I can't do what they do. I know what I can do, but I can't do everything; I ain't gonna front like I can.

There’s a real emphasis on craft with the people you play with on the record — people who are true experts at what they do, like Blake Mills on guitar.

I love Blakey. He's an insane guitar player and a good friend. We've been playing together for almost a decade. And yeah, craft. Capitalism is pro-mediocrity. Capitalism would love nothing more than for craft to die. And there would be no technicians, only wack-ass guitar players out there.

You’ve talked before about how you value the live version of a song much more than the version that’s on the album — that the recorded song is more like a demo of a live version. Does that change when you’ve got 20 people on the record, doing things that won’t always translate live?

Not only is the live version the definitive version, but it's the present version, whatever the present version is. We're alive and have to be with each other, and help each other, and share — that's what's happening at a concert. It's people, in a room, sharing music, together. I see it as very egalitarian between the audience and the performers on stage, and the technicians behind the mixing desk and the lighting — even the bartender. Everyone is sharing the space, and the music that's being created is what were experiencing. It's about whatever is present in front of you. Love your life is what I'm saying.

I see the record, the whole fetishization of recordings — whether it's recorded music or recorded history — it becomes a trap. Some record collectors, they pride aesthetics on such a high level, that they end up knowing nothing about what makes music tick. They could tell you all about these obscure bands — and they’re correct that these bands are brilliant. But they seemed to lose, in their obsessive minds, that music is intangible, and it's ever-changing and growing, and that it's this massive power that can actually transform our global consciousness. That could come from any direction. Usually, when it happens, it comes from the least likely place. It's usually never based on aesthetics.

What's in it for you to make a record, then?

The way I like to think about it is that it’s a totally other thing. The live concert is this crazy expression of community. There's hundred of people, all communicating together to make this music, but in a studio, there's only six or seven people. So let’s use this for a different purpose. Let's use the tools we have for a completely different form of technical expression. That's why especially on this record, I was like — I'm not an engineer like that, compared to some — that's why I wanted Rob, the producer, and Dan, and Brian, the engineer, these brilliant technicians, to express themselves. It's not even the same song. It might piss some people off, but I view it as a completely different thing.

Rachael Pony Cassells

Rachael Pony Cassells

“The struggle continues. Maybe they changed the name from the Vietnam War to Iraq, but we’re still fighting to create a world with no war.”

I want to talk about just how silky smooth this record sounds. The lyrics aren’t talking about pretty things, but I think this might be one of the prettiest records you’ve put out.

I guess from my perspective, it’s like as we go in to talk about the subject matter, we wanna create a rhythmic language that creates a basis, a real basic bed for the ideas contained in the lyrics to live in. A real solid foundation. It’s all bass-driven. Every song, bass is the foundation of the song. Which is my favorite instrument, personally. I love the bass. To me, it’s about creating a revolutionary attitude, and just being cool as a cucumber and creating a rhythmic language that is cool, you know. And what I mean by cool is ice cold, ice-blooded, just an ice pick. Because we’re gonna talk about some serious things, here, and we’re gonna have a good time. It’s gotta be able to do both. It’s like when we create the rhythm, it has to be able to swing from “Laughter Is the Best Medicine” to “Bum Bum Bum,” which have very similar rhythmic language to them, but lyrically are pretty different.

The sound is somewhat disarming, in that way, but I think that’s another aspect of this jammy vibe: the sound tell its own message of community.

Right on. I also feel like that’s just what came out. Hindsight’s always 20/20, and we can look back and we can try to describe why we did that, but honestly at the time, it was just like, we got the people in the room and I got the guitar part, and then the drummer just counted it off — one, two, three, four — and then everyone just does their thing. I mean really at the end of the day it’s just people being themselves, you know.

I just don’t think we’re really that complicated. Like all this talk about brilliant musicians, Frank Ocean, I don’t know. I haven’t heard him. Everyone says he’s the greatest thing since sliced bread, I don’t know. And that’s great, if he’s as great as everyone says he is, I hope he is. But I think there’s a lot of exaggerating going on there. There’s a lot of hyperbole out there. And if you ever front like you’re humble, then you’ll get rolled over like a steamroller, you have to front like you’re the bee’s knees, and then people believe your bullshit. I don’t like it. Shit’s changed.

You recently put out a music video for “Medusa’s Outhouse” that was filmed on porn sets. You’ve always had somewhat conceptual music videos. How’d you get into doing that?

I didn’t make any videos for the first four albums I made. When I started that wasn’t even like an apple in anybody’s eye. The only people who made music videos back then were, like, complete tools. It was lame to make videos. But then I made a couple that were kinda fun, and I was like, Oh I can see this going in a fun direction. I can see this being a medium to explore some topics that I wanna propagate. Such as animal cruelty, for instance. I think it’s about a willingness to work with filmmakers — friends in this case, usually — and having serious conversations about what we want to say and do.

It’s such an intentional medium, filmmaking, like songwriting but for different reasons, completely different reasons. You begin by having a conversation about as extreme of ideas as you can manifest. I really like film people because generally they’re people people. Like if you go on a film crew, from the lighting guy, the makeup person, the camera guy, everyone is a producer, everyone is on the set and everyone looks everyone else in the eye. And there might be the director or whatever bossing people around, but that’s his job to do that. But truly, everyone is on the same spiritual wavelength and I think that’s really cool. So I think when you go in and make a music video and you’re just talking in the conceptual realm, it should have that same kind of level playing field. Any knuckleheaded, crazy, psychotic idea is welcome. All you have to do is challenge it, if it’s not sitting right. I just enjoy it.

When I first reached out to you it was about Chelsea Manning, with the idea to asking you to add a verse to your song “Bradley Manning” from a few years back and incorporate everything that has happened to her since then. And you said you’d already written a story about it.

Yeah, just coincidentally like a year ago, I had written “Chelsea’s Imagination,” and it’s a three-part story. When she changed her name to Chelsea, I didn’t feel comfortable at least for a while playing the “Bradley” song. I didn’t want to hold her to that name if she wasn’t comfortable with that. So I started to write a new thing for Chelsea, not Bradley. But it didn’t want to be a song, it wanted to be like, a spoken-word song. Like a story. Somehow fitting it into regular rhyme meter seemed too close to the “Bradley Manning” song, and I wanted to separate it from that whole thing. Like, the whole “Bradley Manning” time was such a very tumultuous and specific moment for a lot of us that when I wanted to write a follow-up I didn’t want it to remotely resemble anything like that. Chelsea changed her everything, I wanted to change, too, for her.

That was around the time of Occupy Wall Street, too, which I know you were involved in and reference on the new album. Looking back at that time, and what seemed like a collective feeling of hope in protest, though, it just seems so quaint.

The struggle continues, that’s all. It always has. I can remember mid-’90s and stuff, you know. Shit changes, it just does, that’s what it’s about. And if you hear any of the old school activists, the people who were there in the ’50s, ’60s, civil rights, anti-war activists, they’ve been right there the whole way. And they’re like, “Yeah, it’s changed, but like, one thing’s the same, we’re still struggling for civil rights. Basic fucking human rights. And war’s not going away, we’re still fighting for that.” So things change, and maybe they changed the name from the Vietnam War to Iraq, but we’re still fighting to create a world with no war.

“I’m against extroverted personalities, I’m against talking heads, I’m against cult of personality, rock & rollers who wanna kiss ass and make everyone like them.”

Another thing around that time was the leak of a Sky Ferreira song called “Rancid Girl,” written by you and Blake Mills. What’s the connection between that song and the “Rancid Girl” on Mangy Love?

It always began with a poem that I wrote, called “Rancid Girl.” And I had shared that with Blake, and they went off and did their own version that was, from what I understand, inspired by it. There’s a Woody Guthrie quote that goes, “We wrote these songs, which is all we ever really wanted to do. So now you have them, you can change, them you can rewrite ‘em, yodel ‘em, we don’t care.” So they went off and did their version, I had nothing to do with it. But I told them, one of these days I’m gonna wanna do my own version. And they were like, “Cool.” So the new one is that poem. Weirdly enough, it was written the same day as the lyrics for Big Wheel — like the same character, the same voice, it’s the same person — that weird kind of machismo lunatic.

He’s kinda mean.

He’s not mean! It’s all love, man. It’s a song of admiration. What are you talking about mean? It’s not mean. Because there’s a girl? It’s harsh. But it’s not mean. The whole time he’s going, You’ve got rancid skin, rancid blood… He’s saying you’re rancid this, rancid that, but hey, I don’t mind! I think you’re great. The whole time, that’s the tone.

When it comes time to record an album, and you’ve got all these songs from overlapping time periods, how do you pick which goes where? Do you look for a cohesive theme, or does that cohesion come from the instrumentation?

Well, usually it’s me picking them. And this is what I get accused of a lot, a lack of brevity like we were saying earlier. Before it was like, Well, these are the 25 songs I’ve been working on this year, and we’re just gonna have to listen to them all. I’m sorry people, but that’s just where I’m at. I did that a handful of times. I got that out of my skin, the whole “revealing my sketchbook” kind of thing. I think I’ve been naked for like a long time. Full frontal nudity, for like a decade. People were like, “Cass, put some pants on.” So that’s one of the main reasons I wanted to work with Rob, because he really helps choosing which songs would create a story. I came to the studio with my acoustic guitar and he looked at all my lyrics, I sang ‘em all, and we just talked about ‘em, like, “What’s it mean? What is it trying to do? Does it have anything to do with this other song? Are we repeating ourselves here? Is that redundant? Or does one enhance the other?” We just talked about it like that. He’s done it so much that he knows what to look for. I really trusted him.

One of the really effective sonic moves is when the Reverend Goat Carson is speaking underneath your singing on “Laughter Is the Best Medicine.” Where does an idea like that come from?

We’ve been friends for many years, and he was the featured guest in my second of two “County Line” videos. But the way we recorded that was very simple. We sent him the lyrics and he spoke the lyrics. That simple. It’d be like if I sent you the lyrics. I send you the lyrics, and you say them. Just say them, into a tape recorder. And I think when we do that, rhythm is created. Maybe the cadence of how we speak, it becomes musical.

Just him recording himself, no band?

Yeah, no band, just at his home in New Orleans. Came out and recorded that. To me it’s a blessing. Literally a blessing. He’s blessing the song. He’s blessing the listener. We need more blessings. We wanna think we’re all badass atheists all the time, but sometimes we just gotta give it up to the spirits. That doesn’t necessarily have to come from a man, not necessarily. But ancient people always had a medium through which the spirits spoke. I know everyone wants to take ayahuasca and all that, and that’s good, but the ancient techniques of ayahuasca were a lot different, like only priests took it. Not white tourists from the North. That’s a new thing. I think it’s a little bit of both. It’s a little about self-exploration, doing your own studies, but also listening to the elders and being open to receiving the blessings through them from the spirits.

In a musical sense, too, this album seems concerned with history — bringing in the Phish bassist Mike Gordon and all the jamming stuff.

It’s about who we are today, you know. Where we at now. Everyone wants to talk about the future. “We’re going into the future!” What’s all the anxiety about going to the future? There’s an insane amount of speculation and anxiety as we head into the great unknown. It’s a dead aphorism, but we could at least enjoy the ride, you know. And that’s what it’s like to me. Enjoy the ride. So that means folding time, learning as much as we can about music history, folding it all the way overlapping to the distant future, to the end of time. What does the end of time look like? No time. And that’s what today is. To me, that’s what it would resemble.

What do you mean?

There’s no time in the present. We’re continuously locked in the present moment. Like as soon as you try to put your finger on a present moment, it’s fleeting, correct? So, there is no time. We live in fractions of the universe. Each word that we say exists in a separate universe. Where we are, in a musical context, is where the formless — ancient peoples or ancient consciousness, the Big Bang, or whatever, when the waters moved upon the waters and all that stuff — when that folds with what our experience leads us to believe that the future might look like. And that’s what today is. That’s why I say “resembles.” Because even though we’re living today, it only resembles existence. It’s only the semblance of reality. Nothing is really real. Because it’s always fractioning into separate, different universes. It only resembles present moments, or reality, if you want to call it that.

I guess I can see, now, the bummer that is the recorded song.

It’s not a bummer! I mean, there’s a lot of other things in the world that are more of a bummer. And that’s the other thing, I don’t think we should be afraid of being bummed anymore. When I was a kid, Primus was the big band, and their whole thing was Primus sucks. “I suck, you suck, we all suck. Primus sucks.” And it was somehow liberating to accept that not everything is this perfect squeaky clean Debbie Gibson — I mean, I like Debbie and everything — but not everything’s perfect. What’s all this anxiety about people trying to force themselves to be happy and positive all the time? That’s good, too, but I just feel it’s a bit oppressive. It’s monomania. It’s the flip side to Poe: instead of being monomaniacal about death, we’re monomaniacal about life. And that’s even more terrifying to me than Poe. If that’s possible.

On your Instagram page, is that you posting all those archival photos and old concert flyers? Do you run that page?

Some I’ve sent to my manager, and some I’ve started to do myself. I’m real, real new to this stuff. I’ve always been a total luddite, anti-personal-broadcasting. I’m against extroverted personalities, I’m against talking heads, I’m against cult of personality, rock & rollers who wanna kiss ass and make everyone like them. I’m totally anti- that. But after being in the game this long I’d figured I’d try to teach an old dog a new trick every once in awhile. Maybe not a whole makeover.

It’s also just nice to see those old photos exist.

I agree. It’s cool to be tight with people after all those years. That’s the miracle. To still have friends like that that you can rely on. That’s real. Fuck the music business — that shit’s real.