Shane J. Smith’s Photos Explore Our Tangled Relationship With Technology

The Brooklyn-based photographer, who shoots for The FADER, talks us through his thoughtful practice.

Our social lives are more intertwined with technology than ever — and no one knows that better than teens and twenty-somethings. Despite the option of wandering aimlessly within the pixelated territories of Instagram and Twitter, 23-year-old photographer Shane J. Smith has chosen instead to analyze the state of his generation. The Maryland Institute College of Art graduate constructs symbols within his hauntingly beautiful images to refer to societal constructs and common inner grapplings. “I'm always trying to talk about two or three things at one time,” he admits, chuckling at me from across The FADER's conference room table on a hot July afternoon. His youthful subjects — alongside his personal projects, he’s shot a cluster of teen musicians for The FADER, as well as the indie band Lower Dens — explore commodity, technology, superficiality, and vulnerability by way of cotton candy, bottles of Hennessy, and Google glasses, amongst other things. Find out how the St. Louis native began creating such carefully orchestrated photographs, how he protects his craft, and how he learned to survive in New York.

When did you pick up photography?

My family always had those little point and shoot cameras, the little 35mm ones. I don't remember when I started doing it, but I've always had my own rolls of film. I still have pictures from a super long time ago. I guess when I really got serious was in high school; it was a school that went from 7th to through 12th grade, and they offered art classes. They had what would be the equivalent of foundation early on, but once you got to 9th grade you could just choose to do photo. I did photo for those four years.

What do you shoot with now?

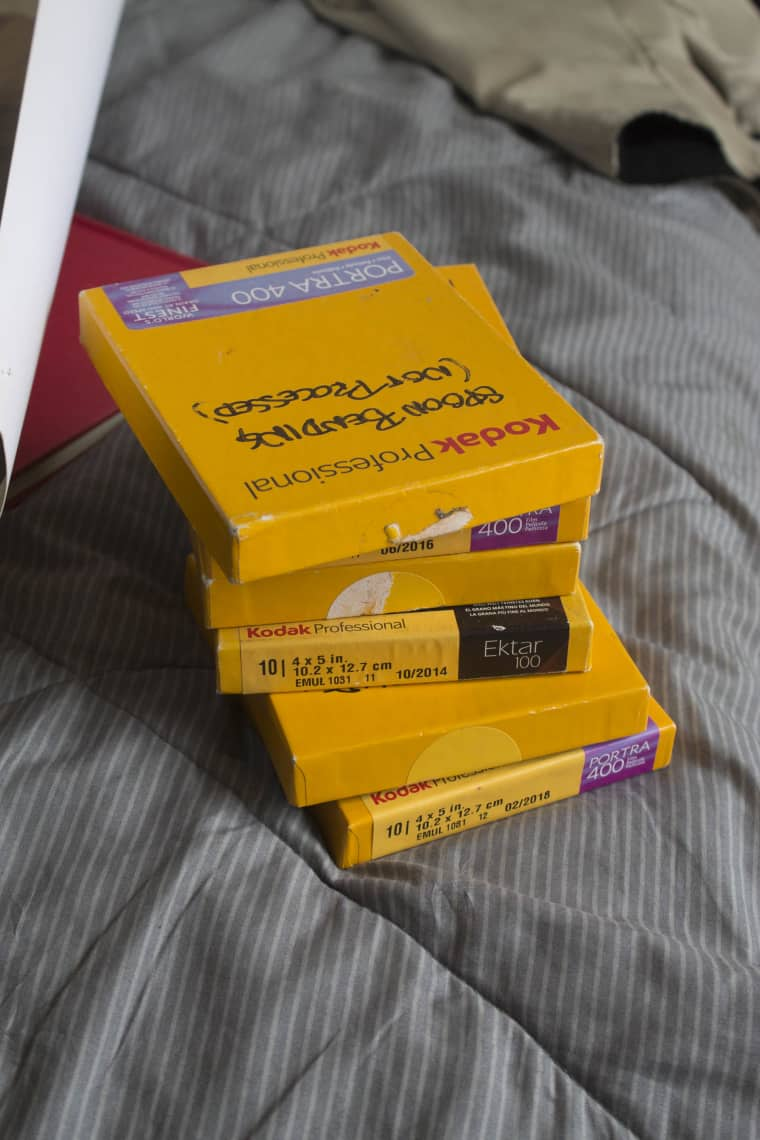

Since I moved here, almost everything is people telling me to shoot stuff for work, so I got a Nikon D810 when I moved here. I had one job where I shot with my 50D, and it was a really low light setting — it was like the second week I moved here — and the job I was working on fell through; terrible image quality. So I bought the Nikon when I was planning to buy a 4x5 camera, cause that's all I shot with during my last two years of college, that and a 8x10. I just borrow film cameras now from friends.

When did you come to New York?

I lived here between junior and senior year, because two of my friends were on the New York path and they needed a third roommate, so it just made sense. Plus I found internships and everything, so everything pointed towards going here. That summer was super hard. I had two really low paying internships, while living in a warehouse in Bushwick. So, that made me almost not wanna move back, but then I decided to move back after I graduated.

Could you talk a bit about these internships?

Bonni Benrubi Gallery, which is now just Benrubi Gallery, I worked there when they were still in Midtown, during the summer when they were transporting their archives to Chelsea. It was a really good learning opportunity because I worked there and at Splashlight Studios as an equipment assistant. My friends that I moved here with were gear guys and they were like, "You have to do this or else you're not gonna be able to survive." I worked at Splashlight on night shifts, then Bonni Benrubi during the day. It was this weird experience of looking at thousands of photo prints and writing like, "There's a scratch." Or "There's a pinprick on the corner," and then going to Soho and carrying huge heavy equipment. There was no knowledge in the equipment stuff, it was just carrying gear and that's it. It was like no sleep during that time.

“I try to make everything like big, cohesive stories. If I take one moment out of the story and post it up on Instagram, it might be a pretty picture, but no one’s gonna get what they’re supposed to get from it.”

What are some of your biggest inspirations?

When I first came to college, my whole goal was to become a lookbook photographer, because of the stuff that was going on was like A$AP Rocky, Odd Future, black Tumblr. But then I met this kid in freshmen year that was all about "master copies," like people that will take a Caravaggio painting and paint everyone in with like basketball jerseys or something; trying to make the old stuff new. I started doing that with digital. By the end of sophomore year, I was really into studio stuff, like tableaus, and I had this teacher that was like, "You need to use 4x5 cameras." She hit me with all the light photographers like Jeff Wall, Crewdson, and Atta Kim, like all the people who made really intense, constructed photos. So I guess that was the biggest turn, because I went from trying to put people in cool clothes and trying to make them look cool, but then when I got the 4x5 camera, it switched more to me creating as an artist.

When I started constructing the photos and staging stuff, then more of my natural influences in life — comics and sci-fi movies and video games — were able to find a place. That being said, I am influenced by some artists: Jeff Wall and Atta are my favorite photographers, hands down. They influenced me since they put really good questions in their art; I always wanna look at their art, like that shit’s loaded. Like Jeff Wall's stuff is calm, but it's very loaded, especially the photos that are looking at social scenarios. That's kinda how I found what I think my voice is, just being aware when I see social interactions; that it might be representative of something bigger and then bringing that into the studio.

Speaking of social interactions, what do you think of Instagram?

On Instagram I'm more of a troll, because I know people are going to my Instagram for my art, which I, 99% of the time, don't give them. People will be like, "Why do you only post selfies or like non-art stuff?" and I'm like, "I don't know, it's Instagram." People that want my art can go to my website. You know, you have your young ass, 17-year-old photographer that has like 35K followers, that might actually be a really creative, good artist, but I know people are just gonna be like, "Oh, they're just one of those Insta-famous photographers." I'm so scared of that kind of stigma around me that I try to keep my art practice and what I'm really doing with my art completely offline. I try to make everything like big, cohesive stories. If I take one moment out of the story and post it up on Instagram it might be a pretty picture, but no one's gonna get what they're supposed to get from it.

Technology has a large presence in your work. Why is that?

It all started when I had this weird life transition in school when I took some time to go back home. One of the main things that I did was go to this butterfly and plant conservatory they have there. I noticed there was a lot of really old people and they'd sit down and just stare and take things in, but the young people would come in and be like, "Oh my god" and take pictures with their phones all day. Just watching that defined for me that we're redefining what memory is. Apple knows that live photo is cooler than not-live photo because you can remember things even better. Those kind of ideas kinda took over my mind for like senior year because I was thinking about things that were concurrent with me getting older. Plus virtual reality and augmented reality, like FaceTime, Skype — all these things that are trying to make a deeper connection over a longer distance, when we still haven’t really come to an understanding if it is an enriched connection. If you have family in another country, of course being able to FaceTime is a good thing, but if you're FaceTiming with someone in the house with you — which we've all seen happen — that may not be as healthy of a progression.

I started trying to escalate those analogies in my photos, like there’s a photo of a girl and a guy holding hands and he has a virtual reality [headset] on [in Smith's photography series Slant]. The strongest moment is a triptych I took that was taken with the Google Glass, a drone, then a 4x5 camera. The first picture is him with the Google Glass on, controlling the drone with his phone. You have all these different sight-lines that are going between the drone to the guy, to the glasses, to the phone, to the girl who's just looking at the drone, so not actually looking at the guy. That was the simplest way for me to say, "We might be looking at each other, but we're not." I'm not saying that I agree or disagree; I was playing Pokemon on my phone on the way here. But, I think it's important to know what these surrogates for memory are doing to us on a bigger scale.

“I think it’s important to know what these surrogates for memory are doing to us on a bigger scale.”

Commodity also plays a significant role in your photographs, like in your collections Fairy Floss, Programs, and Lessons. How would you describe the relationship between material objects and people of our generation?

For the objectivity of cotton candy [in Fairy Floss], I was at a weird moment in life. My teacher told me to take a picture of the happiest thing you know, and I made a long list and cotton candy ended up being one of the things invented just to bring people happiness. Most of the kids in the series were late teens, early twenties, so [cotton candy] was a good way to bring these worries that we have, like our quarter life crisis, and try to bring it back to a time where we didn't have many worries. The cotton candy is what evolved into much heavier moments, like having the girls wearing the Rothko canvases and being auctioned off (in Lessons). I'm including images that can kind've represent a physical way to communicate what a group of individuals are wrestling with in real life.

When editing photos or shooting, what do you listen to?

When I was shooting for The FADER with the classical music students and there's this kid who's played cello for 10 years, I'm not gonna put on the new Future mixtape. Maybe he does like it, but at the same time, it's way better to play it safe when you're shooting; read your subject and try to feel it. For me, it is good if I can put on my Soundcloud hip-hop people and just vibe out and catch that wave with them, but it varies. But when I'm editing, I really like those guys that make jazz beats that sample videogames, like Knowledge; he's kinda the grandfather of that whole thing. Like Knowledge, Poptart Pete, Delofi; it's very relaxing. If I listen to too intense music while I'm editing, it makes me too aware that time is passing.

What’s up next?

It seems like a lot of different tangents are leading up to the same thing. The woman who I studio assist for, she’s at her first year at Yale right now, [and] she brought my portfolio up to Gregory Crewdson. And he said "You should have this kid apply [for a masters] this Fall," so basically everything's leading to that now.

I have this new photo series that's based around the idea of a death camp kinda scenario, like that one movie where all of these Japanese kids at a school have to kill each other, Battle Royale. The new idea is making the same analogy but about New York and the experiences I've seen. I've seen kids that are in the art world, or just New York at large, it's like being a crab in a bucket. As soon as you see one of your peers doing what the rest of the group wants to do, you pull them back in. Or I've seen people that all boost each other towards the same goal. Or people that aren't even thinking about the rat race and they're like, "I wanna spread love amongst the population." I'm trying to talk about ideas like that; it's hard to describe exactly how it'll take form. Also, I'm a boy scout/eagle scout, so the troupe mentalities are coming into it. I linked with a set designer who's gonna help me with this because I wanna blend the studio stuff but still shoot the way I do in the field. There's a lot of new moves I'm making for this series that are bigger endeavors. Hopefully it comes together.