Yung Lean was in a mental hospital around this time last year.

It was Mount Sinai in Miami Beach, the city where he’d been recording demos and rough drafts for his third full-length project, Warlord. He was 18, and, though usually based in Stockholm, had spent two months in the city, working for the first time in a professional studio. It was called the Pink House, and it was in a pink house, down by the ocean with a pool out back.

Lean had ended up in Miami after a stateside tour that his 27-year-old U.S. manager, Barron Machat, had helped arrange. Barron was a beloved and respected figure in the North American experimental music scene. Known for his belief in the crossover potential of thought-provoking acts, he and his label Hippos in Tanks were said to have “ushered avant-garde music into the 21st century.” Though he didn’t release any of Lean’s records, he helped Lean start a label of his own, Sky Team. In Miami, Barron had an apartment where Lean could crash, and connections: his father, Steven Machat, is an entertainment lawyer whose clients have included Ozzy Osbourne and Bobby Brown. He is currently running for the U.S. Senate.

A number of fellow Swedes accompanied Lean on the trip. There was Yung Sherman, then 20, one of his longtime producers and the sonic architect of Warlord, and Bladee, 21, a frequent collaborator who sings background vocals at Lean’s live shows. And there was Emilio Fagone, Lean’s 29-year-old primary manager, who’s been working with him since he was 16.

After the recording sessions wrapped in Miami, Sherman and Emilio flew back to Sweden. But Lean and Bladee stayed behind, with plans to play some shows then head up to New York. “I remember I felt like, Why is he going to stay?” Sherman says now. “Why isn't he just going home? We've been away for so long, what is he going to do here now? It seems unnecessary for him to stay.”

Lean’s stage name comes from his given name, Jonatan Aron Leandoer Håstad, but also from lean — codeine syrup. By his own account, in Miami he was heavily addicted, not just to lean, but to Xanax, marijuana, and cocaine, and combining the drugs daily to troubling effect. Lean found himself slipping into characters that were hard to shake. He started dressing like a nurse, in hospital scrubs. He began to carry a knife. Most nights the drugs kept him up, so he’d sit out on a balcony, writing a book in his iPhone called Heaven that retold childhood nightmares about people turning into rats — the animal sign of his Chinese Zodiac. Lean showed the book to Barron, and Barron told him it was too dark, that he shouldn’t be writing it.

At some point on April 7, 2015, Barron left Bladee and Lean in the condo. Lean’s nose started bleeding, and he checked in on Snapchat; his girlfriend, back home in Sweden, happened to have a nosebleed, too. High and overcome by feelings of connectedness, Lean became detached from reality. He started to destroy the condo, throwing furniture and breaking glass. He was bleeding from the debris when Bladee called 911.

In the hospital, Lean became paranoid that he’d been separated from his hard drive. After midnight, in the early hours of April 8, Lean says he managed to call Barron and beg him to bring him his files.

It was a typically pleasant Miami spring night, with a clear sky and a comfortable temperature of 75 degrees, when Barron set out, with a 21-year-old producer from L.A. named Hunter Karman in the passenger seat. According to the police report, he was driving about 60 miles per hour when he veered out of his lane and ran into a traffic signal post. The car twisted into the intersection, and the engine caught on fire. According to Lean and Steven Machat, Barron had taken Xanax. Strangers rushed in and managed to help Hunter from the flaming wreck, but Barron was stuck. He died in the car.

Heartfelt tributes posted online remembered his good taste and generosity — how he’d keep places just so acquaintances could stay in them, and scramble to encourage his artists’ most out-there ideas, like a dubstep magic show. “He was the most high-minded, cosmic person anyone ever met,” said d’Eon, once signed to Hippos in Tanks. “He constantly spoke enthusiastically about how culture was at a tipping point, that we can do whatever we want musically and in business, because we were living in the cultural Wild West.”

At the same time, Lean’s father was flying to visit Lean in the hospital, where he stayed for four days. Lean says he didn’t recognize him at first, but they returned to Sweden together. For about two months, Lean’s father tended to him while he recovered in the countryside, in relative isolation, before moving back into his parents’ place in Stockholm. Lean was then and is now under what he says is “heavy medication.”

Back in Sweden, Lean’s other main producer, Yung Gud, set about finishing the album. The files that came back from Miami were a total mess, with missing stems and distorted vocal takes. Working with Sherman, Gud spent months reconstituting incomplete tracks, restructuring unsatisfactory ones, and calling in Lean to re-do vocal parts. In November 2015, the album’s first single, “Hoover,” debuted with a music video featuring a dirt-bike rider jumping over a cemetery and a medic shining a light into Lean’s vacant eyes. The single went up for sale on January 20, 2016, and Lean announced that Warlord would be released the following month, to be supported by an international tour that would bring him back to America.

But just five days after the announcement, a different version of Warlord appeared on Spotify, and for preorder on Amazon and iTunes. Its full title was Warlord (This Record is Dedicated to the Memory of Barron Alexander Machat (6/25/1987 - 4/8/2015)). Instead of the abstract cover art Lean had teased on Instagram, it featured a crude pencil drawing of a Lean-like character giving the finger. Fans who listened said the songs sounded unfinished, and expressed confusion over the small-print copyright, which seemed to attribute the release to the label of a man who had passed away: “Hippos in Tanks A division of the Machat Co,” it said on Spotify.

The person who uploaded that album was Barron’s father. According to business documents filed with the state of Florida, but unbeknownst to many, Steven Machat was an equal managing partner in Hippos in Tanks.

Reached by a phone number listed on his Senate campaign’s filing papers, Steven says he believed he was within his rights to release the Warlord demos because he helped fund their creation. “I wanted that album out to remember Barron,” he explains, expressing frustration that Lean had flown home before Barron was buried. Lean’s team was predictably unhappy about the release: “They went nuts, ‘How can you put this out?’” Steven says. “And I said, ‘Well, fuck you.’ But then I heard God talk to me: ‘Steven, they’re evil. If you reverse evil, you live.’ I analyzed [the music] and realized what they were doing, and I took it off.”

“There’s nothing good about Lean,” he adds. “Yung Lean worshipped the darkness.”

When Yung Lean was just eight months old, he moved with his family from Sweden to Belarus. His dad is a poet, fantasy author, and noted translator of French literature; his mom works in human rights, supporting LGBTQ communities in Russia, Vietnam, and throughout South America. Russia was where she’d grown up, and Lean says the move to Belarus was partially because she wanted her son to have a childhood similar to her own — though his memories probably aren’t as fond as hers.

“One day my dad was gonna pick me up from kindergarten,” Lean says. “All the kids were playing, and he's like, ‘So where's my son? Where's Jonatan?’ They’re like, ‘Jonatan has not been good today,’ and he’s like, ‘But where is he?’ They point at the corner, and they’d put me in the corner with, like, a KKK hat. What do you call it? A dunce hat. I'd been standing there like that for maybe five hours.”

Even after the family returned to Sweden, when Lean was 5, he would never be great at school. He and his friends often wound up in petty trouble, getting busted for doing graffiti, as happened with his producer Yung Sherman, or smoking weed, as happened with Lean. He got a job at McDonald’s, but he did eventually use school to his advantage: the academic computer lab is where he recorded parts of his first mixtape, Unknown Death 2002, before dropping out in 2013, when he was 16.

Released that same year, his debut was an instant if divisive sensation, particularly in the United States. Here was this baby-faced white kid with a foreign accent and a strangely lazy flow, rapping with a simple formula, more or less: drugs, depression, and offhand references to pop culture. Yung Lean incorporated all three, in just three lines, on “Ginseng Strip 2002,” an early success with 10 million YouTube plays. Poppin' pills like zits/ While someone vomits on your mosquito tits/ Slitting wrists while dark evil spirits like Slytherin slither in with tricks. It’s easy to see how he could be dismissed as a goof, or even plainly repelling, but he also attracted real fans, consistently selling out big clubs in a series of U.S. tours.

Lean emerged at a transitional time in the way music is talked about online: sites that once trafficked MP3s now produce earnest thinkpieces. And he was a perfect subject. On music blogs and in The New Yorker and The New York Times, he was treated like a puzzle to be solved. What did Yung Lean mean for rap? Was his music tongue-in-cheek, intentionally bad in an attempt to mock how hollow the genre had become? How did his race play into the attention surrounding him, or how his lyrics were received? How did his nationality? Was he commenting on consumerism, or was he just a wayward teen with a sweet tooth for Arizona Iced Tea?

“The concept is definitely not that complicated,” Lean says, disavowing any critical underpinnings to his music, as he always has. “I just make videos and stuff, there's not much more to it than that. I’m a musician trying to express myself.” He describes his choice of genre as merely one of circumstance. “If it was the ’70s, I'd be a punk artist. I was just born into hip-hop.” This is a fairly common statement from white rappers: cheap software is the new power chord, and rapping is simply what’s relevant now. But it’s an idea that also comes from a privileged position, one that sidesteps rap music’s origin, so founded on the black, brown, and Latino experience — and the experience in America, at that. Lean may have been born into a world that loved rap, but he can only ever approach it as an outsider.

“You could have a lot of reasons to be angry at a white rapper,” says his producer Yung Gud. Born Carl-Mikael Göran Berlander, he’s of mixed race heritage — his grandfather was a Nigerian man who met his grandmother, a Swede, in London, and started a family that Gud calls “the result of racial tourism.” When it comes to white rappers, Gud says, “You have people like Slim Jesus and this Stitches dude that just fuck it up. They do weird shit that they shouldn't do because it's serious.” By serious, he means serious: the way “centuries of forced labor and oppression [created the need for] the black hip-hop community to actually have its own arena to do things.” But then Gud introduces a twist. Coming from Sweden, he says, “I wouldn't say we have the same acute responsibility as a white American to step aside.”

For Swedes, American culture is simultaneously alluring and oppressive, Gud says. “We look at screens and we’re fed with American information, American music on the radio, American games, American everything. It's so vast and immersive, but it's also so infuriating what it does to the world.” After playing shows in America, he sees the place as “total anarchy, the worst of the worst and the best of the best,” especially compared to a small socialist country like Sweden. “As a foreigner, I feel like our approach to grabbing U.S. culture is just a part of making yourself heard, getting your presence felt.”

But asserting yourself isn't easy, Gud says, when you come from a country where modesty is a deeply ingrained cultural value. “We have this very firm idea of just keeping quiet, being useful, and taking exactly what's yours — preferably a bit less.” That poses a particular challenge for someone interested in life as an international musician, where competitiveness and self-promotion can be key. One potential path, Gud suggests, is that of a “technical, educated, calculated producer like Max Martin,” a Swede whose work behind the scenes, assisting other artists, has made him one of music’s most prolific yet least public-facing hitmakers. Another, it appears, is Lean’s way: to borrow from a place with bigger egos. For a wannabe rapper from Sweden, perhaps, to do something new you have to first be a little bit something you’re not.

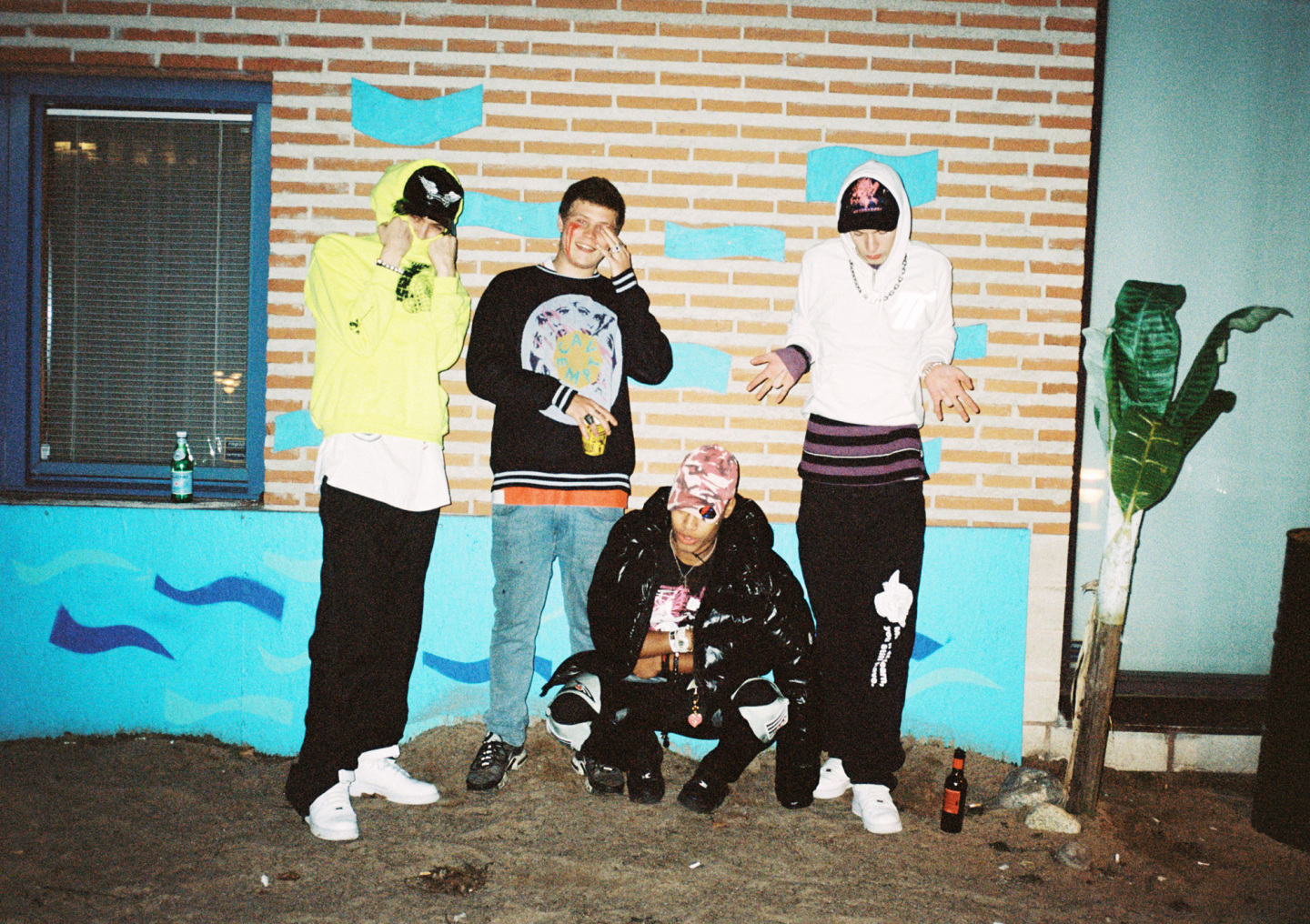

Yung Sherman, Yung Lean, ECCO2k, and Bladee, in Stockholm.

Yung Sherman, Yung Lean, ECCO2k, and Bladee, in Stockholm.

Gud’s fascination with America wasn’t enough to make him want to come back there for the early Warlord sessions. “We already did the rockstar thing,” he says, “and it’s exhausting.” With Sherman willing to handle production duties in Miami, Gud decided to stay in Sweden. There, he focused on “Getting up in the morning, having breakfast, and saving my own life.”

Lean had visited the city before, in 2014, and it set the tone for his return. “We had a rooftop party with Goth Money, Iceage, and Lust for Youth,” he remembers — an American rap group, a Danish punk band, and a Swedish electronic act. “All of us doing coke and smoking blunts. Very good crew, very good mix. And then some guys from Odd Future came with their, like, skateboards, and they just looked at us and walked away. They were like, ‘This party's too much.’”

Being in America, Lean says, always made him want to seize life to a superhuman degree. Everything was so different, it was like it didn’t count. “We come from a very non-materialistic lifestyle,” he says, “and just, you know, anxiety. At 21, people in Sweden will be like, ‘My life is over, and I'll just work for the rest of my life.’ So once you do get to the U.S. and someone meets you at the airport and gives you money and gives you drugs, we go too crazy.”

For Yung Sherman, that fantasy feeling was only more extreme by the beach. “Neon signs and palm trees and guys doing steroids, tight fucking tank tops and fast cars,” he says. “That doesn’t really feel real for someone from Stockholm.” Born Axel Tufvesson, Sherman comes across as the most introverted member of Lean’s crew. He says he had a hard a time in school, too, and only made the grades for a job-training university, which he dropped out of to focus on music. Recording Warlord was a whole new experience. “It was very weird for me to sit in a studio, and outside the studio there was a big pool, and then there was a big sea.”

Perhaps as proof of his discomfort, the harsh, typhoon-sized beat for one of Warlord’s defining tracks, “Miami Ultras,” was composed not in the studio but on the pier beyond it. Sherman says there was a full moon on the night he made it, working on a laptop and headphones while his legs dangled over the water. “During the night, it was very scary,” he says. He and Lean, with his shouted delivery on the track, were influenced both by their location and by sounds from home, specifically a creepy track called “The World Fell” by a Danish synth-punk band named Vår. “It has a really rough, beautiful vibe,” Sherman says. “A bit squeamish.”

Yung Sherman

Yung Sherman

Bladee

Bladee

“Miami Ultras” set a new high-point for Lean’s sound. Part of that is owing to the fact that, as his producers have grown from teenagers to adults, they’ve quite simply gotten better at making beats. Like Lean’s own personal Max Martins, they were always meticulous, first in the more sampled, slacker “cloud rap” style of “Ginseng Strip,” and then in more unique, wholly composed productions like “Yoshi City,” from Lean’s first studio album, 2014’s Unknown Memory. The vibe on Unknown Memory was chilly yet oddly pretty, but on Warlord the sounds became even colder. Cute synths turned darker, and buildups got more dramatic, for an overall effect that’s less like stateside rap production and more like European hard trance — mixed with synth-punk and pop. In talking to Gud, practically the only time he mentions American acts is to complain that people have said he sounds like them. Like Sherman did with Vår, he prefers to reference more local sounds: djent, a Swedish style of progressive metal that sometimes features sample-based percussion, or Addis Black Widow, a Swedish R&B group from late-’90s that sounded kind of like Craig David.

Lean’s wordplay and delivery has always been less dynamic than superior American MCs. But on his most successful new material, he makes the best of his natural monotone by simply amping up his energy. He doesn’t sound like — or sound like he’s trying to sound like — Future or Drake or Young Thug; he attempts no vocal feats in his flows. Instead, on “Miami Ultras,” Lean comes across more like the punk artist he says he might’ve been, outright shouting as he repeatedly hammers the same notes. It’s a subtle but effective shift: the aura of detachment that made him seem jokey or sarcastic has been replaced by a feeling that’s more aggressively jaded. Gone, too, are the gimmicky references to pop cultural trinkets, exchanged for something more haunting: when Lean talks on “Hoover” about waking up covered in liquor, with his coke bag empty, he is speaking about his real life.

The video for “Miami Ultras” was filmed in the countryside of Sweden after Lean’s recovery. He appears alone in hospital garb, bloodied, with an I.V. in his arm, digging a grave. There is also a separate teaser for the track, posted on his Instagram, that incorporates found footage of Miami: rainstorms rocking palm trees, and for a fleeting second, an overturned, burned-out car.

“If everything that happened didn't happen, I guess like we could look back at Miami as a fun time,” Sherman says. “But it went just shit.”

Lean is equally blunt. “I’m blessed to still be alive. I could have died, for sure.”

A few months after Lean returned to Sweden, he took a job at a factory. While Gud was cleaning up Warlord, Lean joined Sherman, Bladee, and whitearmor, another producer who helped out on the album, on an assembly line manufacturing shampoo. “We’d just stand there pressing buttons,” Lean says. “We’d put music in the speakers, dance around the factory. It was very nice. It’s like Lou Reed: after he did some tours, he went home and worked in his dad's factory. You can’t always be on the top, you know?”

During the slow return to normal life, he grew closer to his father. “Back in the day we used to fight all the time,” Lean says. “I'd throw spaghetti at him, and he'd take out all the stuff from my studio in the basement. Not a violent relationship, but a very angry relationship. Ever since he picked me up in Miami and we spent the summer together, we got really close. We're good friends.” Part of their newly shared understanding is the realization that they’re both “freelancers,” as Lean puts it — his dad with his writing and Lean with his music.

At first, Lean’s medication often made him tired, and his balance was off, but once he got used to it he started to exercise, and with an interesting group of people. He got in touch with a musician named Avner, who’d caught his attention with a Swedish-language cover of Daniel Johnston a few years back. Avner suggested they go running together once a week. Lean started taking boxing lessons, too, coincidentally in a class with Thorbjörn Håkansson from The Embassy, a crucial band in the development of Swedish indie-pop.

Fifteen years ago, The Embassy started a label called Service, which released the first album from one of Lean’s favorite bands, The Tough Alliance. There’s an old story in The FADER about The Tough Alliance, how they were polite and unassuming in person, but when they’d perform they didn’t bring microphones; instead, they’d yell and swing baseball bats at the crowd. “From the American point of view, I guess it’s aggressive,” Lean says, “but I could relate to the whole attitude.” His favorite Tough Alliance song was “My Hood,” which came out when he was in the fifth grade, a song about loving where you’re from but also feeling disgusted with the place.

When Lean started taking ecstasy a few years later, he got into the group JJ, who incorporated drum samples and quotations of American rap lyrics with ambient music and dream-pop. They were signed alongside Avner to the label The Tough Alliance created, Sincerely Yours, and, altogether, helped make up a formative, bratty scene in Yung Lean’s development. Punk in ethos but poppy in sound, with songs full of bright synths that were shadowed by anxious lyrics, these bands took the influence of America and created a uniquely Swedish response.

“You know this type of music only happens once every ten years,” Lean says The Tough Alliance’s Eric Berglund told him once. “You guys are us ten years later.”

On the February day that Warlord is finally released, in its completed form, I take a train 30 minutes west of Stockholm’s center to the suburb of Sâtra, where Lean now lives alone. It’s a short, cold walk from the station to his second-floor studio apartment, reached by an outdoor hallway that overlooks a scraggly bit of leafless trees. When Lean opens the door, wearing a soccer jersey, Polo pants, and Gucci slides, he lets loose the sound of reggae music and the smell of incense.

His place is homey, with big plants and bright light streaming through tall windows. A Gustave Doré print of Lucifer getting kicked out of heaven is on the wall, and a Renaissance-style tapestry functions like a curtain around a mattress on the floor in a little nook. Little Yoshi pillows dot the couch.

Lean is candid in his responses to my questions, up to a point. He walks me through the trip to America, how their crew was “in fancy Miami but living a dirty lifestyle.” He calls Bladee an angel for helping him when he was overdosing. He says he loved Barron, who he calls “one of the most blessed guys I've ever met.” But he says there is a limit to his memory about what happened after he blacked out, and I sense there is also a limit to his comfort with talking about it. “I was in a mental hospital. That's all I wanna say. I don't wanna say anything more,” he says.

He gets up to prepare coffee and switches to a moody, eclectic playlist: The Tough Alliance, Grouper, Lana Del Rey, and iLoveMakonnen’s most despondent song, “Down For So Long.” I say that I don’t know if Makonnen will be making anything like that for a while, since he seemed to be getting more into party music, and Lean says, “I don’t like party music. I like emotional music.”

It’s in that spirit that Lean has started work on a new album. Currently in demo stage, with 12 tracks so far, Lean says it will be produced by Kendal Johansson, who worked with The Tough Alliance. Joakim Benon from JJ has agreed to play guitar on it, then Lean wants to send the tracks to Kanye West’s engineer Mike Dean, who helped out on two Warlord tracks that were recorded before Miami, to add more guitar and polish off the production. Lean says it will sound like Daniel Johnston mixed with Lil Wayne. There won’t be any rapping.

He plays me a few of the demos. The first is vintage Sincerely Yours, with guitars that are almost uncomfortably bright — picture you’re lying on the beach, which would be nice, except someone has stolen your sunglasses. Pretty close to his normal voice, Lean sings lines like I left heaven for you, and, Having nightmares on the road again, and a bare chorus: I know what it feels like/ I know what I know now. Another track features just him and a piano.

“I'm gonna release it as Yung Lean,” he says, even though it doesn’t sound very much like Yung Lean. “You put out three rap albums, then you can do whatever you like, I think.”

When Lean returned with “Hoover” last year, after months out of the public eye, I noticed a few exhausted tweets from non-fans: Why is Yung Lean still a thing? In his apartment, I ask how he interprets the criticism. “Everyone says Yung Lean is disposable,” he says. “Like, ‘Yes, finally we can jump on a trend and jump off it next year. Let’s wear some Nikes and dance to Yung Lean, then he’ll be gone, the artist will be dead.’ I’m not a temporary artist. We're not like disposable humans that you can throw in the trash.”

For outsiders making rap music, success often comes down to how well you handle your role. It's an endlessly complicated position, and many fail. “The main hip-hop channel in this country still sounds like fucking Pete Rock or some Primo Gang Starr shit, and it sucks so bad,” his producer Yung Gud told me at one point. “[Most Swedish rappers] never tried to make their own thing. They just took what they liked and they did another copy of that, they just made more of it. We don't need more of that anymore. We need new things.”

Lean is at his best when he engages America’s influence while standing outside of it, and Sweden’s influence while standing outside of it too. For a teenager from a small country in an ever-globalizing world, the grass is always greener on both sides, but on songs like “Miami Ultras” and “Hoover,” or the ravey “Hocus Pocus” featuring Bladee, Lean has found his own spot on the fence in between. That’s how he achieves the something new that Gud is after, but it can be unsettling because, even if Lean’s not trying to, his music involves a lot of unsolved problems — of race and privilege, and of the way cultural exports affect the world.

The music Lean is working on now is unique because, more than ever, it offers him the chance to speak as an insider. He shares real experiences with Lil Wayne — the author of one of rap’s most vivid drug-abuse songs, “I Feel Like Dying” — and also Daniel Johnston, an American songwriter who, like Lean, is known for lyrics that are simple to the point of sounding naïve, and who, more to the point, has been diagnosed with schizophrenia associated with, and some say triggered by, an LSD trip that landed Johnston in a mental institution in 1986.

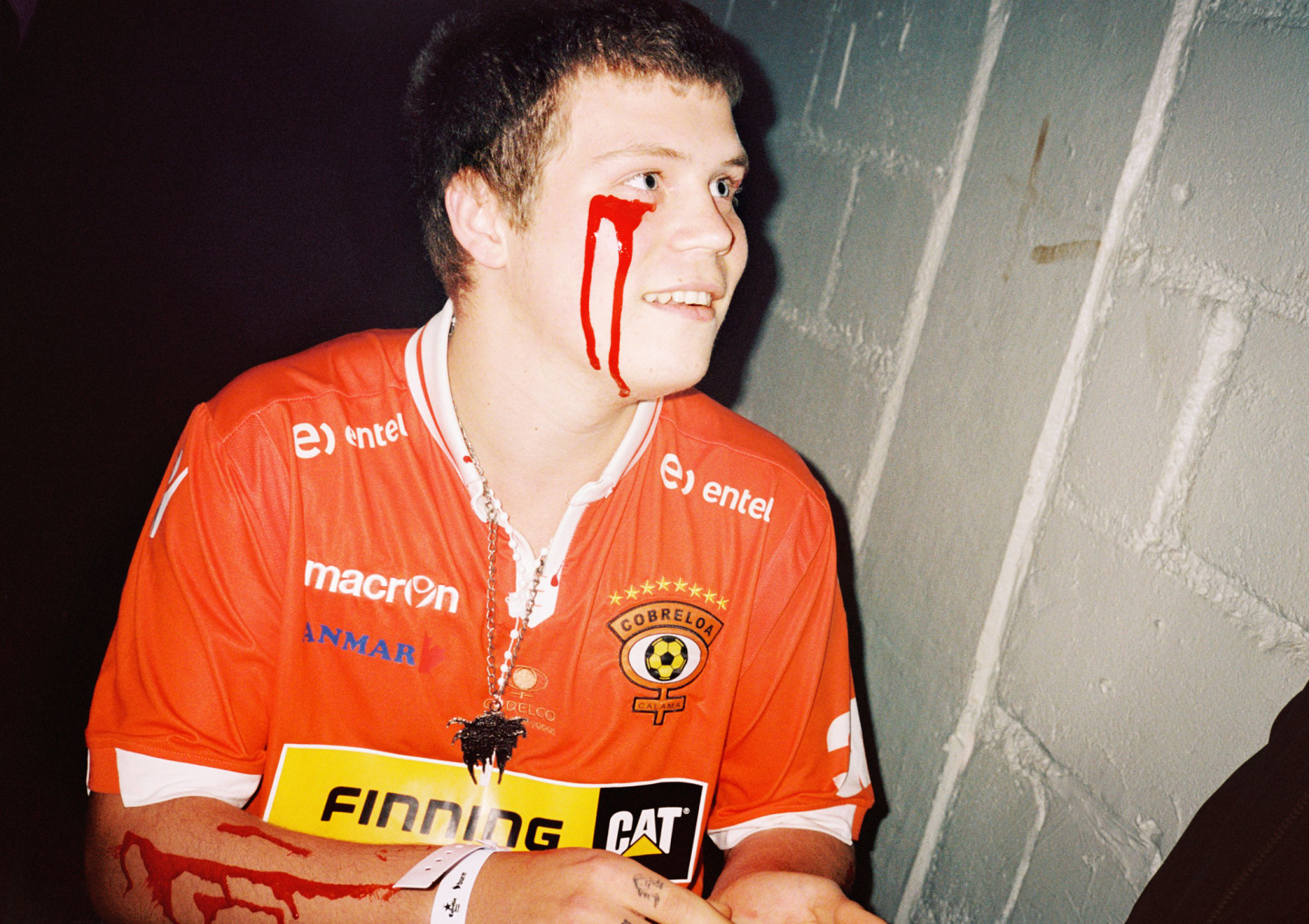

Later on the night of my visit, Lean performs at a music festival in Stockholm, his first concert there in over a year. The venue has a corporate feel, with lots of glass and exposed wood, and the section for winter coat drop-off is enormous. In a well-lit backstage room, Lean sips nonalcoholic beer, plays cards with Yung Sherman and Bladee, and covers himself in fake blood, in red lines up his arm and under his eyes. His manager, Emilio, is there; earlier, he’d helped recover a Gucci bag Lean left in his Uber. Joakim from JJ happens to be downstairs, playing ping-pong.

When it’s time to perform, Lean and his crew take a path outside, into the cold. He’s shorter than his friends, puffier. He looks like the teenager he still is.

Lean comes out to “Hoover” and the crowd knows every word. He bounces on the balls of his feet, and, in the front row, a young woman with short blue hair pulls her turtleneck up over her nose. Bladee, unlike a traditional hype man, sings over everything, extending Lean’s phrases in an otherworldly doubling effect. The sounds flow together, from one song to the next, each track not quite mixed by Sherman but with tendrils of reverb that connect them. A huge screen behind them flashes images of fantasy and horror, dragons and monsters, dragging you into hell. Between songs, I never understand what Lean says because he’s speaking in Swedish.