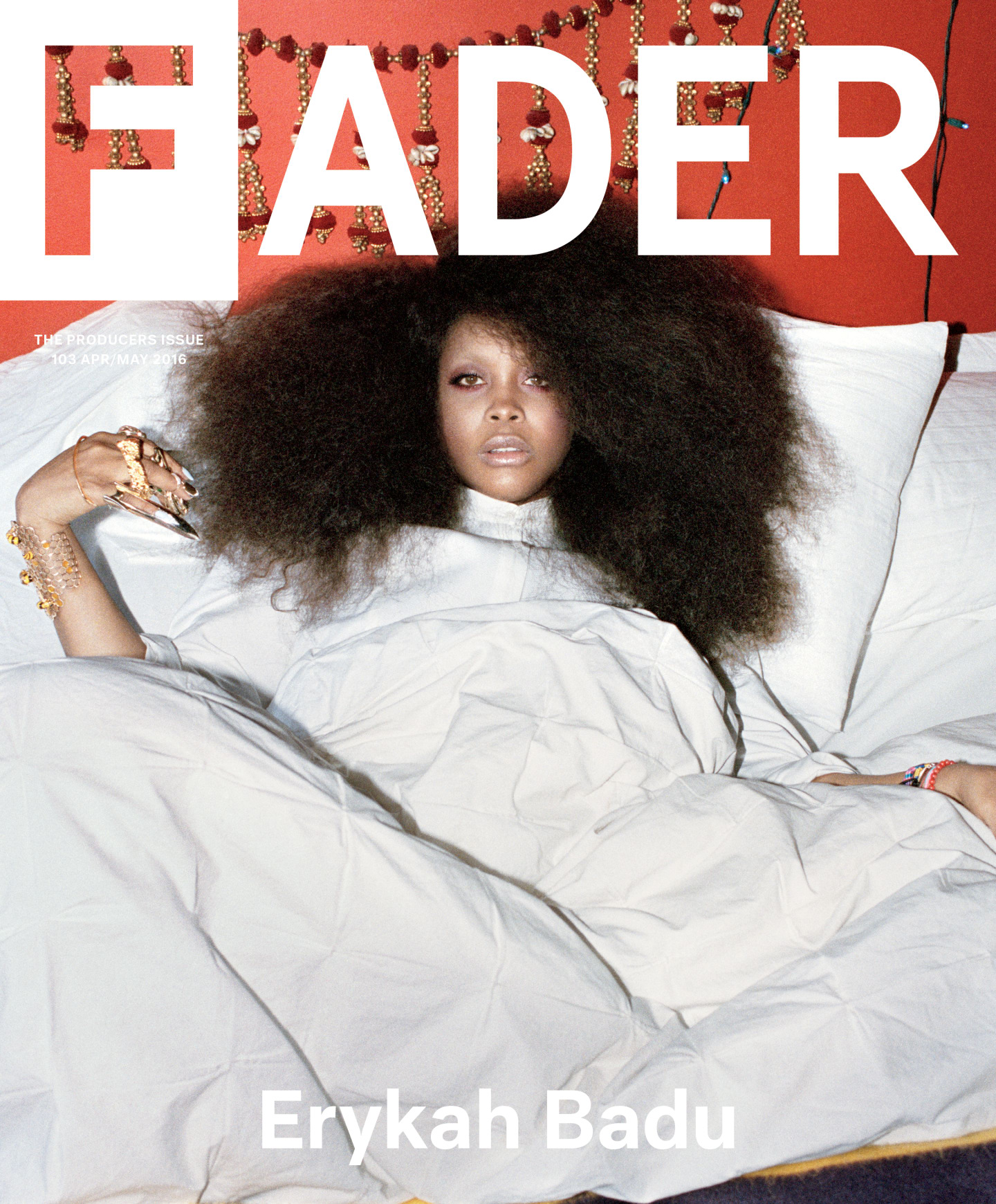

Erykah Badu’s house—surrounded by tall trees and mounds of soft, unkempt grass; the window trims painted in a neon yellow that brings to mind some architect’s eyeglass frames—sits close to the shore of White Rock Lake in Dallas, Texas. Wind chimes drone outside in an irregular breeze. Inside, tracks from John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band play from a series of invisible speakers that blanket the whole place in sound.

As we sit across from one another in her living room, Badu tells me that the speakers were the first thing she bought when she moved here in 1997, the same year she released her debut album, Baduizm. In the intervening years, as she grew into one of soul music’s foremost visionaries—not just a singer or songwriter, but a producer in the broadest, most creatively generative sense—she has filled the house, piece by piece, with art and the means to create it.

Some of the beloved items were made by friends, some by fans, and some by her three children, who all paint whenever a whim strikes. There’s a Wurlitzer against a wall, an electric bass yoked up in a minimalist stand, and a massive collection of records behind a pair of turntables, a laptop aloft between them. There are easels in a leaning stack, and two cartoonish paintings: one of Badu and one of her ex André Benjamin, the father of her son and eldest child, Seven.

It’s late February, two days before her 45th birthday and the concert she’s planned to celebrate it. Through the big rectangular window, we watch the sun’s calm, glinting walk across the lake, and the heaped-together skyline of Dallas beyond. This is the city where Badu was born and grew up, the home to five generations of her family. I ask her what Dallas means to her, and she almost grins. “I just like the air,” she says. “I like the sound of the birds.”

She’s quiet for a while, until suddenly I do hear a chirp, then another. Badu laughs—this is not the sound of her beloved Dallas birdsong. It’s a pet.

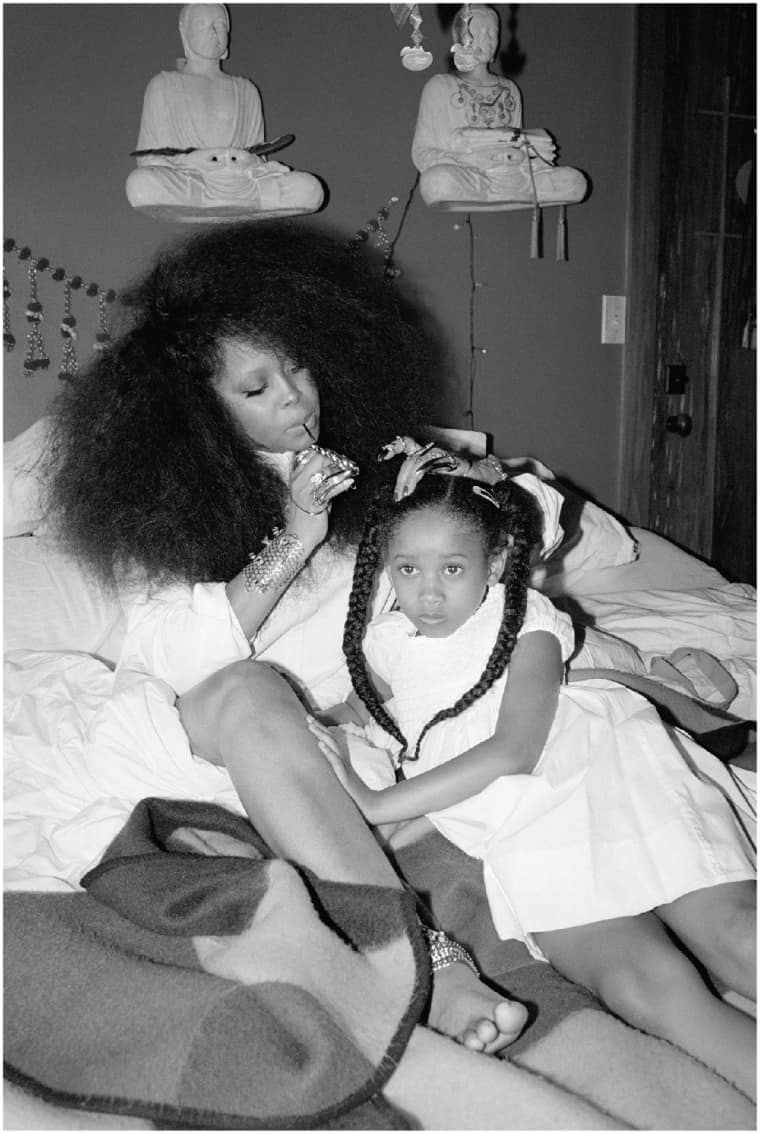

“My mom bought that bird for Mars’s birthday,” she says. “Her name is, uh, Sparkle.” Mars is her youngest, 7 years old. Her father is the rapper Jay Electronica. Badu walks over to the little cage, which is less than clean. “Her living conditions are horrible.” To the bird: “Sparkle, I’m sorry.” To me: “I did not want the bird.” She moves Sparkle nearer to us, into the sunlight. The bird is the size of a skipping stone and moves in quick, bright, paranoid gestures.

“But it’s what I know,” she says, returning to Dallas. “It’s where I’ve created, where I started, where I…” She shrugs: it’s everything. Her family is still the basic unit of reality in her life. Both of her grandmothers are still alive and verging on 90—one was once her accountant, the other her archivist, keeping years of articles and reviews and album covers in a tightly organized set of binders. Both, despite retiring from their official duties, remain, Badu says, smirking, “very actively opinionated in my life.” Her mother is her nanny—“and boss.” Her sister Koryan, or Koko, slips around the house, braids of pale-blonde and purple flowing down her back and past her waist; she is personal assistant, house manager, background vocalist. Her brother sells merchandise. Her cousin Ken is her estate manager and travels with her on tour.

“Gotta pay ‘em anyway,” Badu says. “Might as well put ‘em to work.”

Her speaking voice is very clear, very flexible—even when she’s quiet, or travels down an octave for comic effect, she’s audible across the room. She talks in a continuous negotiation between a drawl and a song. Two huge braids tumble out of a knit hat and down her torso; her toes are painted the same bright yellow that accents the house.

I start to ask a question and realize halfway through that she is looking past me with her eyebrows furrowed, her mouth set sardonically. “Say that again?” she says. “I was looking at Seven.” Before I can repeat myself: “Boy! I thought your dad was picking you up.”

“Yeah,” comes the voice from somewhere behind me. “We about to go eat or something.” Seven—18 years old and skinny, a wide-mouthed second strain of his father walking around in the world—ambles into the living room to hug his mother goodbye.

Later in the afternoon, Badu will meet up with Seven and André—Badu calls her co-parent her “best friend for the past almost 20 years.” An Atlanta native, André moved to Dallas after their son entered high school. The three plan to visit a Buddhist temple to see a priest who gave Seven and André a reading a few weeks ago. Badu says she’s a skeptic, but decided to go along after hearing that the priest told Seven to clean out the refrigerator in his room—something, she says, that he really does need to do.

I ask what’s in the fridge.

“I don’t know, hot sauce with the top off? It smells like hot sauce when you open the door. I don’t go in there, but it’s… just cans of shit, open.” She smiles with obvious pride. “He’s worked real hard. He home-schooled from 3 to 7, so he’s kinda focused. He’s like a nerd.” Seven likes art, designs shirts and buttons, and has studied Latin since the fifth grade: “So he knows how to spell a whole lot of shit.” Next year, she says, in college, “he’s gonna major in psychology and minor in business, so he can trick people into buying his things. That’s his idea.”

Badu’s second child, Puma, is 11. Her father is the Dallas-native rapper The D.O.C. She sings—“She’s just like me,” Badu says—and she goes to a French immersion school, where she is beginning to dabble in Mandarin. Mars, in the first grade, goes to an immersion school, too—hers for Spanish.

“I just wanted to make sure,” Badu says, “that whenever I take over the country, I have a secretary of state, defense, and a peace ambassador at hand.”

“Being a doula, or being a mom, or even, like, making food—it’s just breathing and trusting, and allowing the creativity to flow through.”

We move to the kitchen, where Badu makes an impromptu arrangement of fruit: freshly chopped pineapple in the center, with berries moving in red and blue and purple waves toward the edges of the big squarish plate. She uses four or five long, thin scoops of lettuce as a garnish; on the white spine of each, she places an evenly spaced line of raspberries.

The intricacy of the display is impressive, and I say so.

“Thank you,” she says. “It’s art. Everything is art to me. We’re making art”—this in reference to the interview we’re conducting. “That’s what we’re doing.”

Considered this way, even the kitchen is a kind of large-scale collage: every square inch covered with drawings and photographs of her kids, siblings, cousins, famous friends like Yasiin Bey and the late producer J Dilla.

“This is a high-alkaline lunch,” Badu says. “We’re gonna have a lot of energy.”

We move the fruit to a dining table toward the back of the house, where Badu feeds a spare lettuce leaf to another of Mars’s unlikely, half-wanted pets: a guinea pig named Young Tonya. Nearby, seven painted cardboard boxes sit on a windowsill. Badu tells me that she’s starting the process of writing an autobiography, and that the boxes are a kind of outline. “I just painted them,” she says. “I’m gonna line them up on the table, one for each chapter, and I’m gonna drop things in each box so I can have a visual for what I’m doing.” Red is for family, orange for sex—“baby daddies, love affairs”—yellow for the creative life, green for her work as a doula and “holistic healer,” light blue for music, darker blue for spirituality, and a purple box that she says is a mystery.

Calls start to come, every few minutes. A while back Badu dropped her phone into a bowl of soup, so she has to take each one on speaker.

The callers all have a slightly cagey air, each getting caught up in some weird detail about her birthday party that can’t be explained over the phone. “They like to give me some kind of surprise thing every year,” she says between calls. “And I like to ruin it.”

The only guileless reacher-out is Badu’s paternal grandmother, Ganny. Their exchange is loving, all coos, and ends with Ganny squealing in excitement for her granddaughter’s birthday.

“I’m still not no grown woman,” Badu says.

“I know it,” Ganny says. “You my baby.”

It’s the week before the Super Tuesday primary in Texas, so I ask about politics—by which, of course, I mean that I ask about Donald Trump and the various walls, physical and attitudinal, that he threatens to build.

“Oh, I don’t believe in any of that shit,” she says.

“The walls?”

“Politics. I don’t know how much we have a say…It’s a show, it’s a game. On the smaller scale, I think that your city reps and district reps are very serious about what they’re doing, and then when they get up a little higher it becomes a show. Everybody gets kinda turned out.”

“This is the craziest shit I’ve ever seen in my life,” she says of Trump’s success so far. “Is this real? But”—cryptically, with a shrug—“it will become a reality, if that’s what the plan is.”

Badu points to albums like 2008’s New Amerykah Part 1 (4th World War) as evidence of her own ability, through art, not only to speak to social trouble, but also, in some sense, to anticipate it. Take, for example, her song “Twinkle”: They keep us uneducated/ Sick and depressed/ Doctor I’m addicted now/ I’m under arrest.

“I felt it coming on,” she says, of the police violence crisis that sparked and sustained the Black Lives Matter movement. “I was really feeling a strong affinity toward writing about what was going on around me. And I actually wrote about what’s happening right now in that album. So I don’t feel the need to write it now, because I got it out.”

She sees our political present as a test of seriousness on more than one front. “We can organize like a motherfucker when police beat us up,” she says. “But can we organize to stop black-on-black crime, or poor-on-poor crime? Because, you know, poor is the new black. You don’t have to be black now.”

Positions like these, some of them surprisingly conservative, have become an increasingly prominent aspect of Badu’s persona, especially online—where, weeks after my visit to Dallas, she sparked a Twitter storm by calling for longer skirts in girls’ school uniforms. That she has taken up the tools of current-day virality to spread, and defend, unpopular stances is a paradox that strangely befits her: art, for Badu, begins with the individual voice, however heterodox.

“I think it’s cool what Beyoncé’s doing,” she says. “Kendrick Lamar is consciously writing and effecting change by showing the other side of what happens in his community. Believe it or not, NWA started out doing that too. ‘Gangsta, Gangsta’ was actually a parody.” On the way to her point, she effortlessly rattles off the first verse of the song:

Here’s a little somethin’ ‘bout a nigga like me

Never should have been let out the penitentiary

Ice Cube, would like to say

That I’m a crazy mothafucka from around the way

Since I was a youth, I smoked weed out

Now I’m the muthafucka that ya read about

Takin’ a life or two, that’s what the hell I do

You don’t like how I’m livin’: well, fuck you

This is a gang, and I’m in it.

“It’s Cube’s way of saying: this is what you’ve created. He’s not a gangster. But I think it felt so good to ‘em. Whatever gets you the most pussy, I guess. Activist pussy or gangsta pussy? Gangsta pussy was a little bit more plentiful.”

All of this—the cynicism about the nature and efficacy of political activity, the interest, instead, in humor as a means of protest, if not change, and the throwaway line about sex as counter-incentive to struggle—confirms something I’ve always suspected about Erykah Badu. As a singer and songwriter and performer, the thing that distinguishes her in the history of soul music is her consistent deployment of irony. No one since the height of the blues is funnier, or, crucially, more aware of how her funniness distorts the world around her and the history that created her. With her jerky movements and the rough plasticity of her voice, she is less a descendent of Billie Holiday and Diana Ross than a comment on those predecessors, and on the styles and tics that gave them their power.

This is most apparent when watching Badu perform live, which, incidentally, she considers her most fundamental talent: “Performance is what I do,” she tells me. Onstage, she cracks wise and tells stories between numbers, often setting a premise so convincingly that the entire ensuing song comes off as an elongated, meter-bound punchline. She undermines her most deeply felt ballads, just after they peter out, with a slow, exaggerated spin—the move not of a dancer but of a dancer’s uncanny parodist—or with a melodramatic gesture upward, toward the lights. Hers are performances fully aware of the artifice, and the silliness, of performance. Better than almost anyone, she uses the opportunity presented by physical presence to exert a spontaneous creative control, using familiar material to fashion something genuinely new.

Much of this sensibility, she says, she owes to the absurdity that backlights the blues, one of Dallas’s great cultural inheritances. “That’s my roots,” she says. “We have a part of Dallas called Deep Ellum. Deep Ellum was a deep, rich blues part of town.” She catalogues the legends—her forerunners—who flocked to the place to play: Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Johnny Taylor, Denise LaSalle.

“It’s a dying art,” she says, but not at all wistfully. “It’s fine. It’s the way things are, and you evolve or you die.”

Badu gave birth to all three of her children totally naturally, in the house where she grew up; now she is a fully credentialed doula working towards certification as a midwife. “I love motherhood,” she says. “It’s natural for me. Being a doula, or being a mom, or even, like, making food—it’s just breathing and trusting, and allowing the creativity to flow through.”

Her doula career began in 2001, after she vowed to her friend Afya Ibomu—the wife of Stic from the hip-hop group Dead Prez—that she’d assist with the birth of her child. After a frenzied international flight back to New York and a travail of 54 hours in labor, Badu was there to catch the baby. She has been devoted to the practice ever since. Between tour dates and recording, she’s beset by textbooks, essays, research, anatomy lessons, and shadowing the midwife we’ll see today.

Badu pulls up to the birthing center in a sleek, low-riding black Porsche with a license plate that says “SHE ILL.” Inside, her midwife mentor, a white woman with a halo of short hair, is leading a tour of the large, warmly lit main birthing room.

“She’s got a huge belly,” says the midwife. She’s also the proprietor of the center, and she’s setting a scenario for the small crowd: “The contractions are coming every five to seven minutes, and they’re getting stronger.”

She continues the role-play from pains to happy birth: the pregnant woman barreling through the doors of the center, moaning with increasing intensity, and leaning everywhere—against the bed, the toilet, the wall. At each step, the midwife reveals a possible choice. You might give birth in the tub, or on the bed, or standing in the shower with the water pelting down. Her voice, even when indicating pain, exudes an unsettling calm. It’s possible, listening to her, surrounded by 10 or 15 rapt and terrified future parents, to imagine—or, if you’ve ever witnessed a birth, to remember—the grislier aspects of the experience: the thick, coppery smell of blood, the slick and fishlike retreat of the child out of the body and into the dim but irrefutable light. Clearly, the midwife—so unperturbed, so solemnly comfortable, so acquainted with closeness to death—inspires a wary awe in her audience. The only other person smiling, moving easily, sort of bouncing on the balls of her feet, is Badu.

After the tour, we return to her house. It’s dark now, and the downtown lights flit like static across the lake’s surface. Badu’s sister Koko makes a weak excuse for needing to leave. “I gotta…” she says, “um, go to church.”

“Awww,” Badu says, thinking of her birthday, tomorrow. “You gotta go do something for me! You ain’t going to church on a Thursday night. Y’all are acting funny.”

When Koko’s gone, Badu strolls over to her turntables and does a quick DJ set: Biz Markie’s “Vapors,” Beanie Sigel’s “Roc the Mic,” Musiq Soulchild’s “Just Friends,” Jay Z’s “Hustler,” Carl Thomas’s “I Wish,” “Check the Rhime” by A Tribe Called Quest. “I like to rock the party,” she says, smiling.

When she’s done, we go into the kitchen and eat rice, imitation chicken, and greens from Badu’s yard. Mars runs around, picks food off the plate, then somehow tricks her mother into agreeing to help her count her entire collection of Shopkins, scores of hard, plastic figurines of which I’ve never heard. While the little girl arranges her boxes—“She’s a neat freak,” her mother tells me—Badu explains the schoolyard economy that sprouts up around the toys.

“So say, like, I got two Blowannes, and somebody might have a Molly Moccasin to trade.”

“I already have Molly Moccasin,” Mars says.

“Well, I know that. I’m just using it as an example. Being hypothetical. Can you say that, hypothetical?”

“Hypothetical.” I can’t express how satisfied the child seems to have done it so perfectly on the first try.

“It means, like, a made-up version of the truth. A demo version.”

And so they count, holding each miniature up so that I can see it, calling each by its improbable name: Dressica, Fluscious, Penelope Treats, Peter Plant, on and on. In all, there are 123 of the things—collecting them has clearly been as much the work of the mother as of her child. Mars sometimes starts to hum Rihanna’s “Work,” and Badu hums along. “I love that song,” Badu says.

“You evolve or you die.”

The afternoon of Erykah Badu’s birthday, I walk to the club where the party will happen later that night to meet the musicians in Badu’s band, The Cannabinoids. They’re funny guys in their thirties and forties, all dressed in sweatshirts and stylish sneakers, eating catering and adjusting their equipment in anticipation of Badu’s arrival, so they can do a soundcheck. You can tell they’re used to time as a negotiable item: nobody had a clear start time in mind, they just showed up.

Big Mike, Badu’s gruff yet friendly tour manager, has been with her since the beginning, in ’97. He explains how professionalism works in Badu World: “Her thing is, ‘Don’t watch when I get here. Just have my shit ready when I do. Just do the fuck what y’all supposed to do.’” Sometimes the band is last-minute, he tells me, and sometimes haphazard. “But they always want us to come back. We get more work than we can do.”

The mood among the crew is almost familial; they all joke in the rat-a-tat shorthand you’d expect from a group that has traveled the world together several times over. Somebody reminisces about a fight that once broke out over a missed flight back home from Poland—a fight ended, for good, by Badu, who threw a glass across the room and told everybody to get over it. Another remembers the night when they were all crowded into a small club in London, maybe it was, and sat through a bad rendition of Badu’s slow-building, djembe-propulsed “Bag Lady” by a singer who didn’t know that the song’s creator was waiting just beneath the stage, bopping her head.

There’s a younger group hanging around, too: Badu’s opening acts, including Aubrey Davis, a tall, thin 21-year-old with glasses and a huge, bushy ponytail. Badu found Davis, a rapper and Drake sound-alike known as ItsRoutine, through Seven, whom she has appointed A&R head of her independent record label, Control FreaQ. The central promise of Control FreaQ is to return ownership of its artists’ music after an agreed-upon period ranging from 10 to 15 years, and it’s where Davis is now signed.

Looking slightly anxious in anticipation of his short set, he describes the process of helping to write Badu’s remake of “Mr. Telephone Man,” a New Edition tune turned woozy on Badu’s recent mixtape, But You Caint Use My Phone. “She’d never seen the program I use on my computer,” he says. “But she just showed me so many things on it that I didn’t even know. How to place vocals, everything. She basically mastered the song by herself.”

The process of making Phone reveals Badu as not just a reservoir of creative knowledge but also a willing student, happy to mentor, and learn from, new talent. “The way the kids write today, it’s different,” she says. “The drums are different, everything is trapped out. And I felt like, ‘Ooh, I can do that.’”

She met the tape’s producer, Zach Witness, also 21, after he released a remix of “Bag Lady.” First the two created “Cel U Lar Device,” a remix of “Hotline Bling,” as a jokey birthday surprise for Big Mike, who loves the Drake song. Then, after an overwhelmingly positive reception on SoundCloud, Badu called Witness and asked him to work with her on an entire set of phone-related remakes. The two worked at a song-a-day pace in his modest studio, in the one-story Dallas house where he grew up, ultimately crafting a body of work that proves Badu’s ability to adapt her signature brand of songcraft to modern sounds, and offers a playful analysis of our technology-dependent present.

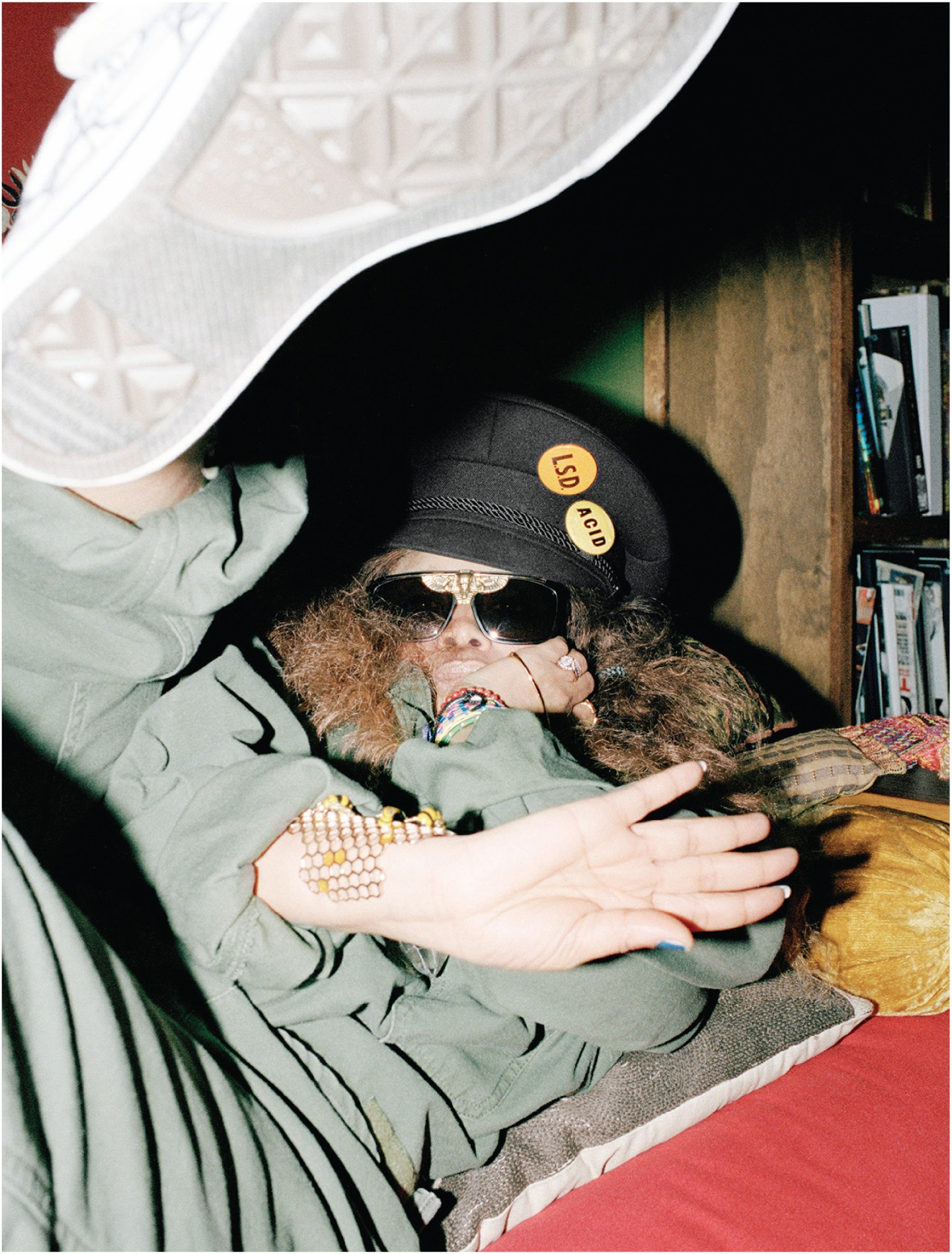

Soon, I hear Badu up on the stage, singing a bit, asking for adjustments to the lights and to the levels on the mics. The backstage empties, and The Cannabinoids head toward their instruments. Big Mike didn’t lie: Badu, standing next to a pink, morbidly detailed replica of a brain, is brisk and exact in her leadership of the band. She wants to achieve precision, and she wants to do it quickly.

Jumpsuit by Urania Terrell

Jumpsuit by Urania Terrell

After the soundcheck, Badu and I drive back to her house. Before her own party, she has to help Puma get ready for a school dance. On the way, she asks me if I want to hear the birthday song she’s chosen for this year. I say sure, and she pulls it up on YouTube, fairly quickly for someone whose hand is on the wheel. It’s Nina Simone, stomping in a long, billowing dress, a set of pearls swaying from her neck.

Be my husband, man, I’ll be your wife

Be my husband, man, I’ll be your wife

Be my husband, man, I’ll be your wife

Loving all of you the rest of your life

Badu sings along as Simone’s shoulders stoop and turn inward. Their voices sound good together like this; each remains distinct, but as the song wears on, they achieve a kind of blend.

“That’s a good birthday song,” I say when it’s over, and Badu says, “Yeah.”

When we get to the house, Puma—dollfaced in lacy pink with black boots—and a friend stand ready to go. Badu fusses over her clothes, her long, spiraling twists of hair, whether she should or shouldn’t wear stockings to the dance. Soon Puma is ready, and her father comes to pick her up. Badu sits fiddling with her phone, making sure she’s put all of her friends and family on the list for her party.

It’s dark when Carl Jones shows up at the house. Jones worked as a producer on The Boondocks and created Black Dynamite, where he met Badu when she came in to do some voiceover work. Now they’re a couple with their own production company; their first project was Badu’s much-praised turn as host of the Soul Train Awards. “She’s got a great point of view,” Jones tells me of Badu-as-comic. “She’s like a modern day Carol Burnett. She’s got so many characters that she does, and she’s such a witty writer.”

Badu slips away to get dressed for the show, and when she emerges, she’s in all black, with a tall, wide-brimmed hat. “Carlito,” she calls to Jones in a sing-song, “can you help me put on my shoes?” There’s a tenderness between the two, a happy silence, and he rushes over, grabs her arm for balance as she slips her foot into the combat boot.

Even on the night of a show, Badu drives herself to work. She puts on a sleek pair of glasses and presses gas on the Porsche with Jones in shotgun, driving how she always does: worryingly but joyfully fast, especially on the on-ramp, swerving impatiently around drivers doing the speed limit. She does a lap around the venue to check out the line, then steers into the parking lot out back.

A back door slides up, garage-like, and Badu steers the car right into the backstage, where, yes, the band, and, yes, Dave Chappelle—the M.C. for the night—and, yes, several light and sound technicians and, yes, family members, but also seemingly hundreds of enthusiastic and colorfully dressed and dubiously necessary hangers-on are milling around. Everybody flocks when Badu emerges from the car. She’s gracious: shakes hands, hugs, takes pictures, embraces Chappelle, takes more pictures—all before she sees the first inch of her dressing room.

There, in a space bedecked with gifts of flowers and intricate plants, she burns a huge bundle of sage and twirls around, quiet, in pirouettes. When the purification ritual is done, she looks happy. She glances around at the contents of the room. “I’ve never had a birthday that was so…floral. So many presents.” The show starts, and she rushes closer to the stage when she hears, of all people, Chico DeBarge.

“Chico?” she says. He’s the younger brother to the old Motown Records family act DeBarge. “Oh, shit. I gotta hear that.”

Soon it’s her turn to perform. I stand in the wings as Badu does what she has told me so often over the past few days that she loves to do. All the spins and asides, the offers of affection to her hometown crowd. The lights—bluish, the way she insists they always be—reach out to her in thin, finger-like strands. She loves to cast attention toward her band, often asking each member to offer a solo, and at some point, when she mentions Koko, who should be behind her, singing, her sister is nowhere to be found.

At the end of the set, while Badu sings “Trill Friends,” her recently released take on Kanye West’s “Real Friends,” something beautiful begins to happen.

Friends, Badu sings. A word we use ev-er-y day/ But most the time we use it in the wrong way…

…and her own real friends, led by Koko, flood the stage, offering her a cake and a thin gold crown that fits over her hat. André is up there—nobody noticed him when he slipped onto the stage—and when Badu sees him and introduces him to the 4,000 some-odd members of the crowd, the roof almost flies off the building.

Soon Chappelle’s got the mic and, for whatever reason, he’s moved to tell a story about driving to the Kentucky Derby with Erykah Badu in the car, when Mtume’s “Juicy Fruit” came on the radio. “I forgot that my friend was one of the best singers in the world,” Chappelle says. “And all of a sudden she is going at it, and the whole car is knocking.”

As he goes on, the band goes into an impromptu version of the song.

“This woman is so special,” he says, and it’s the sincerest thing anybody’s ever seen Dave Chappelle say.

“So let’s give it up for my friend: Erykah Badu!”

Order Erykah Badu’s issue of The FADER, our annual Producers Issue, before it hits newsstands on May 10, 2016.

Hair Urania Terrell, makeup Traci Moore.