Meet OOMK, The Collective Championing Muslim Women In The Zine World

Inside One of My Kind, the London small-press publication exploring faith, art, and identity.

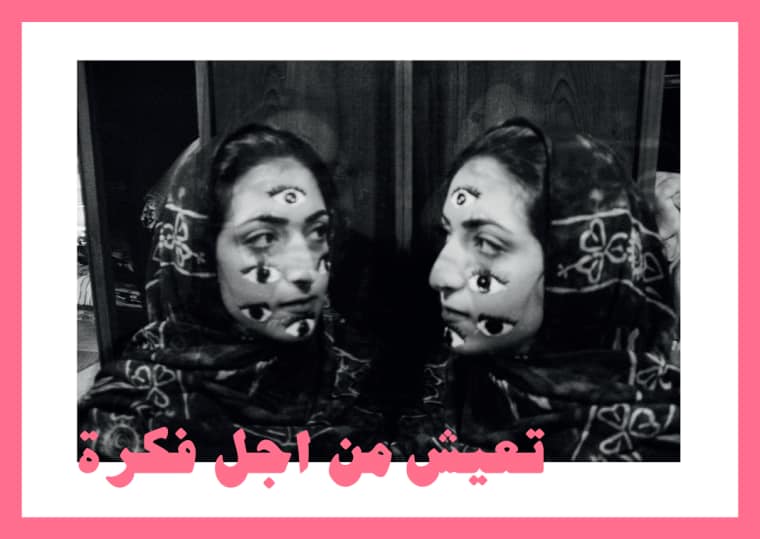

L-R: Heiba Lamara, Sofia Niazi, Rose Nordin, Fatuma Khaireh.

L-R: Heiba Lamara, Sofia Niazi, Rose Nordin, Fatuma Khaireh.

Are you one of my kind? asks Conor Oberst, frontman of indie band Bright Eyes, in a 2012 song written about feeling distanced from the people in his hometown of Omaha, Nebraska. The song might appear to be a surprising choice of inspiration for the title of an independent publication created by a group of young Muslim women, but then it shouldn’t be. The questions that London-based collective One Of My Kind (aka OOMK) explore are those of identity and belonging—issues that are experienced by everyone regardless of whether they grew up defining themselves based on the music they listen to, the hobbies they enjoy, or the religion they practice.

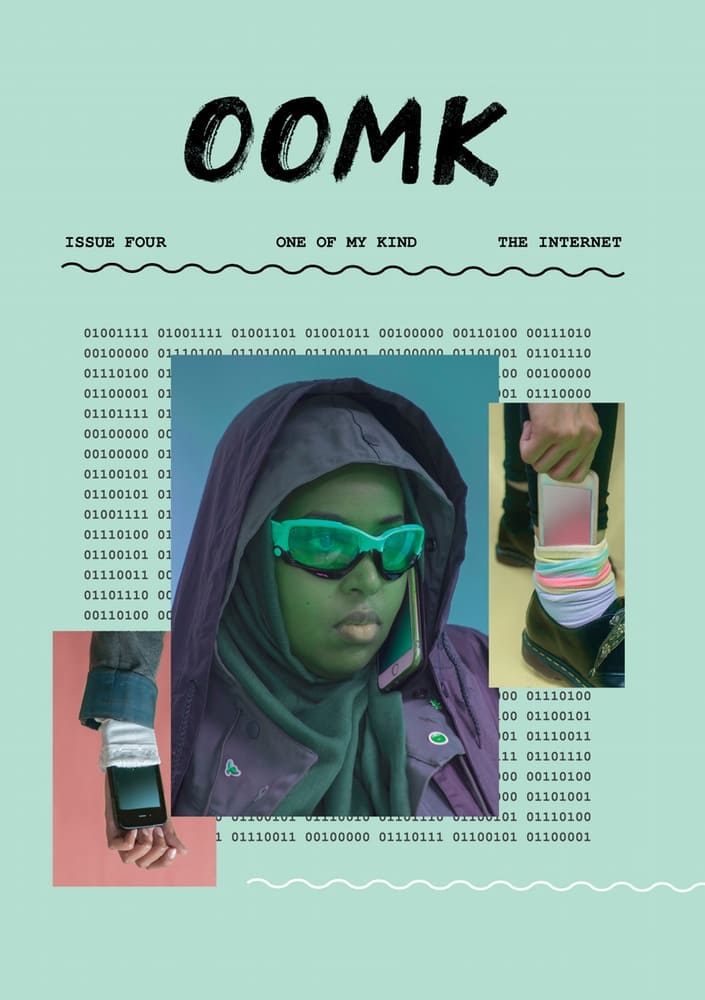

At its core, OOMK is Sofia Niazi, Rose Nordin, and Heiba Lamara, three women from London who produce a highly visual, hand-crafted biannual zine under the same name. (Collective member Fatuma Khaireh is also pictured above.) Although its three founding members are Muslim and the publication looks to be particularly supportive of Muslim women, it is by no means exclusive. Established in 2013 and with content that “pivots on the imagination, creativity and spirituality of women,” OOMK’s four issues have included a diverse raft of contributors, with each zine centered on a different creative theme (to date: ‘Fabric,’ ‘Print,’ ‘Drawing,’ and ‘Internet’).

Zine scans courtesy of OOMK

Zine scans courtesy of OOMK

On a bright Feburary day in east London, OOMK invited me to a ‘think-in’ for their forthcoming fifth edition (‘Collecting’). Located at the art school/community center Open School East, it was a space open to all women, where contributors, readers, or those simply curious to know more about the zine, gathered to discuss ideas and plan pieces for the issue. The OOMK collective members were friendly and warm, and, as we sat in pairs with cups of tea and cookies to brainstorm what ‘collecting’ means to us, it felt like those rare joyous occasions when you got to choose your own groups for school projects. The vibe in the room was open, feminine, and inclusive; everyone was passionate about the publication and each other’s ideas; your voice mattered equally whether you had been a part of building OOMK from the start or if this was your first think-in.

OOMK plays an active role part in London’s small-press publishing community: as well as producing the printed zine and running a collective, they host regular creative events in the city, such as DIY Cultures, an annual day-long festival of zines, comics, talks, animation, poetry and workshops “in the spirit of independence, autonomy and alternatives.”

Through their work, OOMK encourages representations of Muslim women that challenge the one-dimensional depictions of us as the silent victims of a draconian religion. At a time when the climate of Islamophobia initially generated by 9/11 is becoming an ever more terrifying problem both in the U.K. and globally, navigating life as a young Muslim can feel like an onslaught of stereotypes, abuse, and alienation. Against this backdrop, a platform for us to express and define ourselves on our own terms feels more important than ever.

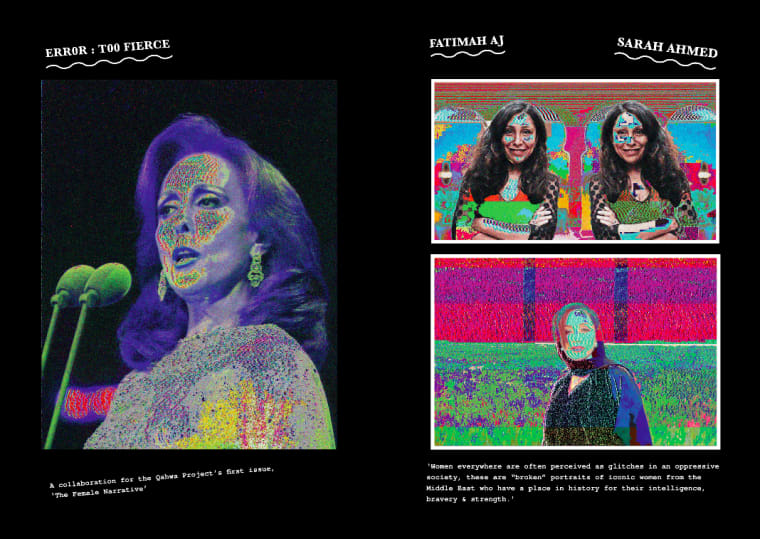

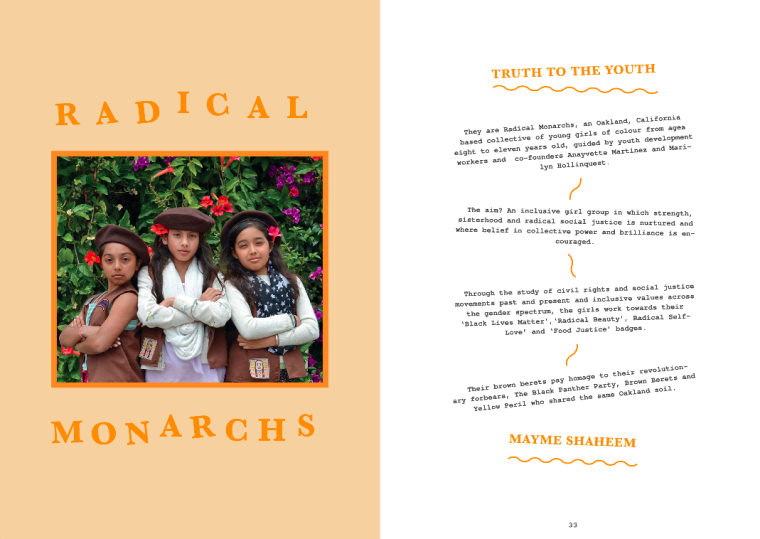

Zine scans courtesy of OOMK

Zine scans courtesy of OOMK

Who are OOMK?

ROSE: We're a collective of around fifteen girls from a creative and academic scene. The actual magazine itself comes three of us: Sofia is the editor in chief, Heiba is the assistant editor, and I'm the designer.

SOFIA: We all used to go to a lot of zine fairs, and I met Rose at one of those. I was like, 'Cool, another Muslim girl!' So we thought it would be really cool to do a publication. Originally we were thinking of doing something about historical Muslim women, but we quickly realized we didn't know anything about history—and that we knew so many interesting women who are trying to capture our world. We thought we'd showcase those women instead.

How would you describe your personalities within the group?

SOFIA: I'm really organized—I also work as a primary school teacher—so I communicate with a lot of the contributors and make sure all the deadlines are met. All of us are very in control of the content, and we all decide together who we want in the zine. We've all got different interests so we'll have our eye on different people, so it's a very collaborative process.

Have you faced issues with diversity in the zine/small press scene?

FATUMA: To be honest I try to only go to things that are organised by other people of color; when I go to wider, more mainstream events, it just seems very insular and masculine. At zine fairs there’s often a feeling of 'you're not meant to be here'—people will come up to our stall and look at our things but they won't make any eye contact with us. You feel invisible. I don't want to go to a space where I don't feel included, and I don't want to buy things from people who don't value me as a person. So generally I prefer attending zine fairs by non-white people because they are actually enjoyable for me, and the zines themselves are about things that I'm much more interested in.

So would you say the scene in a larger sense is still quite white and male?

ROSA: I think [our event] DIY Cultures has done a lot to remap and shift that idea of the zine world, like the traditional image of the Portland white feminist or the east London art school boys being the things that people associate with zine culture. I think the image of the scene is a white boys' club, which is strange because its relation to a history of pamphleteering and activism means that it makes sense that there would be marginalized voices. I don't think it was necessarily our intention to change the image, just to make our own voices heard as well.

“The purpose of the zine has never been to educate anyone; it’s not made for them. If they want to take something away from it then that’s great, but it’s made for us.” —Heiba Lamara

What do you think about the way that women of color are represented in mainstream media?

FATUMA: When I was younger I used to get really upset about the typical depictions of black and Muslim women, but now you have the opportunity to seek out your own media and you don't have to look at the mainstream any more. It's irrelevant. You can tune out all of those things and find what you want to see on the Internet. For me what's more problematic is the policy and political aspects behind the representation that then feed into legislation—that stuff I find really scary.

SOFIA: I don't know what the value is of mainstream, racist institutions trying to represent us, because it's still really damaging to give them that control. Any representation they give us is always going to be on their terms and they can take it away whenever they want, so it seems healthier to be creating your own alternatives.

You're all young Muslim women, which was the founding basis for the zine. What was it like for you growing up Muslim in London?

SOFIA: I grew up in a mixed area in south London, and I had a really positive experience. It was definitely a time where I felt more secure growing up Muslim, compared to the experience of a lot of younger children now.

Was there any point where you felt like you were having a crisis of faith?

FATUMA: Growing up I didn't necessarily ever have a crisis of faith, it was more that I struggled with issues like, 'Where do I exist?' and, 'How do I how fit?' especially as a Muslim woman from an African background. Either my blackness was a problem, or my Muslimness was a problem. As a non-white person, the way that you could fit in was if you latched on to white culture, which meant I spent a lot of time around boring indie white boys who would test me on my knowledge of The Smiths. Being young, like 15 or 16, I never questioned the way that I had to prove my knowledge of this stuff in a way that they never had to. Becoming more religious was a way of disengaging with that and feeling much more comfortable in myself. It reassured of my identity.

“As a Muslim woman, just doing what you want is subversive. And that’s what we’re doing.” —Fatuma Khaireh

In the U.K., the culture of socializing is so centered around drinking. As Muslim women, is that hard for you, or have you been able to find easy alternatives?

FATUMA: There is so much to do if you don't drink! Me and my friends organise a film night at [north west London community center] Rumi's Cave where we have great debates and discussions, and there is attendance from loads of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. The people I run it with aren't Muslim but the space is, so there isn't any alcohol served, and honestly no one even notices. I think most of the time if people are genuinely having fun they're not going to notice if they have a drink or not. You just have to think outside the box more.

Do you see the OOMK zine as a good way to bridge these cultural gaps?

HEIBA: The purpose of the zine has never been to educate anyone; it's not made for them. If they want to take something away from it then that's great, but it's made for us.

FATUMA: OOMK stands for one One Of My Kind and that's just it really—if you get it, then you're part of it and if you don't then you're not. Like, ‘Are you my type of person, can you hang?’ And in many ways that's what all the non-white people in the zine world are doing right now: collectives like Sorry You Feel Uncomfortable, Odd One Out, Typical Girls, Roadfemme, Diaspora Drama, and Motherlands.

Rhetoric in the media about Muslim women can have dangerous consequences, such as David Cameron's bullshit about passive, silenced Muslim women, that then justifies the government's racist policies. To your mind, what is the importance of having a visual medium for Muslim women, who might be ‘unseen’?

FATUMA: We don't necessarily try to present any kind of narrative at all, and in fact many of our contributors aren't even Muslim. But having said that, what is scarier than a Muslim woman who knows her own mind? Policies such as Cameron's are painted in a guise of empowerment but they aren't about what actual Muslim women are saying—because Muslim women who have opinions are [seen as] very scary and very dangerous. I think that's what is subversive about OOMK: as a Muslim woman, just doing what you want is subversive. And that's what we're doing.

HEIBA: That's why it's so important for us that it's in print: it's a visual medium and we want it in libraries and archives so it exists forever rather than just being lost on a website. People can just happen upon it. It's physical; it takes up space.