What My Parents Actually Think Of My Music Career

Two crews from two different cities explain what their parents think of their careers in music.

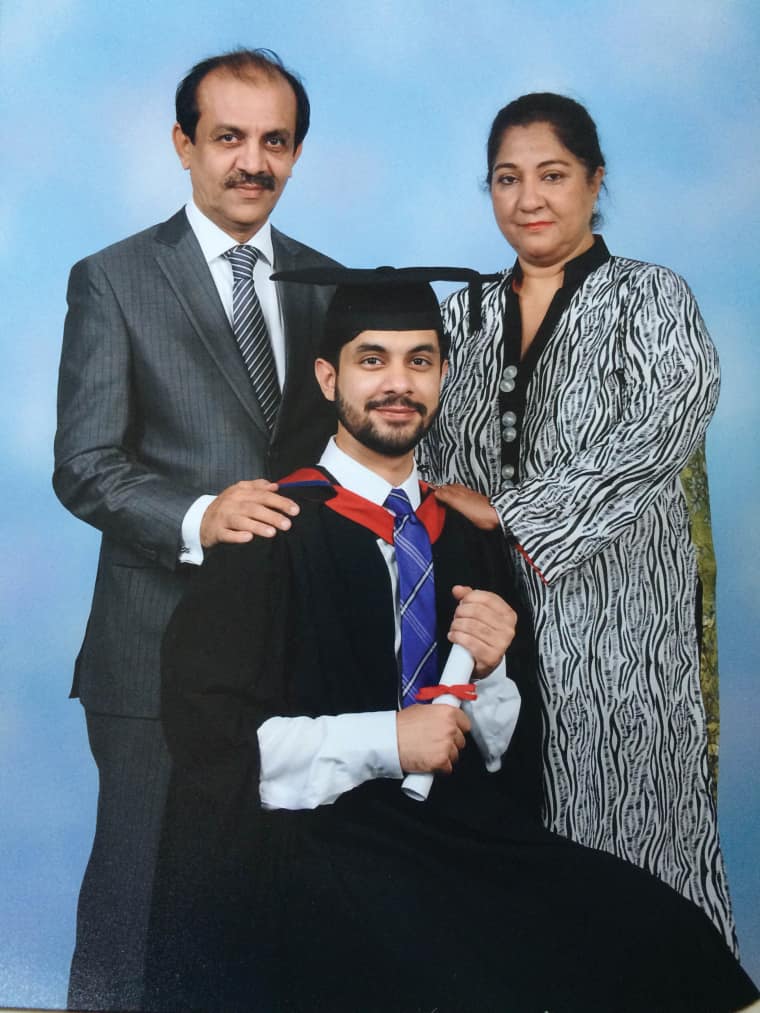

Forever South co-founder Bilal Khan and his parents, Karachi, Pakistan.

Forever South co-founder Bilal Khan and his parents, Karachi, Pakistan.

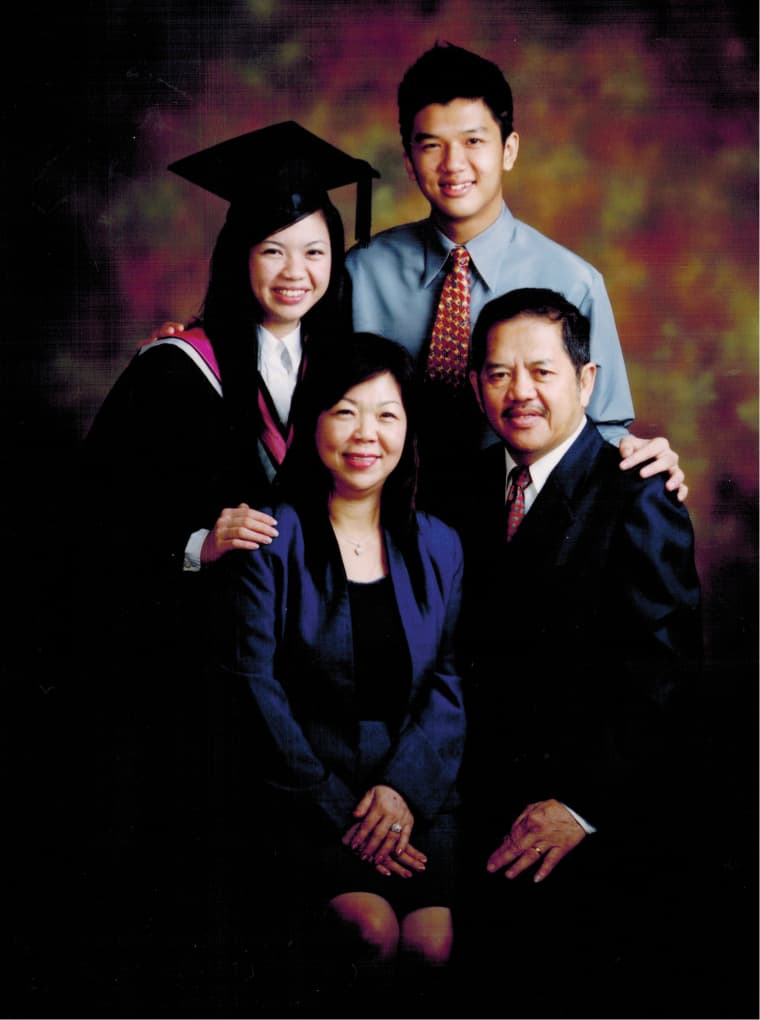

Cherry Chan and her parents, Singapore.

Cherry Chan and her parents, Singapore.

Forever South

Karachi, Pakistan

Bilal Khan [aka Rudoh]: I come from a family that’s really into business. My dad has been a real estate agent for most of his life, then he became an investor. I think one thing that was very important [for my music career] was telling my family, “Hey, I actually want to learn to do this as a science. I want to get into sound engineering.” After that my dad was a bit more accepting about it. He was like, “OK, maybe you could monetize this.” So he paid for me to go to sound engineering school. I was doing law for two and a half years before that, and I dropped out because all I wanted to do was be in a studio making music.

Haamid Rahim [aka Dynoman]: When my dad heard that I really wanted to pursue my album, he was so supportive and helped me think of ideas. I decided to teach electronic music part-time to make money, then I started doing electronic music workshops at high schools—one time, I had this 8-year-old girl come to learn Ableton for about three or four weeks. She was killing it! My dad would connect me with friends of his who needed score work, like advertising radio jingles. I slowly got on my own two feet and I figured it out. My dad would share every article that came out about me, and my mum loved it—she’s really conservative and didn’t know what to say at first, but then she was like, “My son is an electronic music producer.” My grandfather—it’s his 90th birthday in the winter—is really into music, so he’d always be like, “So, you’re a composer?”

“We’re in a society that doesn’t really have a dynamic for the kind of things we do.”—Bilal Khan, Forever South

Khan: Still, we’re in a society that doesn’t really have a dynamic for the kind of things we do. There’s no wider awareness about this kind of music or that people do this for a living, because Pakistan is so unstable due to economic problems and political problems. There really isn’t that much time to think about creating a subculture that can maybe survive. It’s just like, “Oh, my god, I need to make money.”

Rahim: Of course, there were parties going on before Forever South—there was actually a huge jungle scene back in the ’90s. It was even cooler then because Pakistan was a lot safer. It was pre-9/11, and there were warehouses popping off.

Khan: We started Forever South in 2012. It’s a record label, it’s a collective, and we do some shows. We want to do something a bit bigger. We want to work with cultural exchange houses, embassies, and get people to come back and forth. I think we’re done trying to imagine a scene—it’s about time that we really make one.

Rahim: Imagine how cool it would be if Forever South was an international thing. You’d gain all the rep you need to get the kids involved in music. And they won’t have to prove to their dads and moms that this is a career path. They’d just need to say, “Look! It’s done. It is what it is.”

As told to Ruth Saxelby

Cherry Chan

Singapore

Cherry Chan, DJ/promoter: I started my club night, Pop My Cherry!, back in 2004. It was just a night for different kinds of girls to play music at a time when there weren’t a lot of female DJs. It began after I found a whole bunch of weird records when I was studying in Melbourne—I like digging, and I saw things I hadn’t heard in Singapore before.

When my mum first saw that I had a lot of records, she said, “You know what you should do to make money? You should record all of these to tapes and CDs and sell them at the market next to the newspaper stand guy!” I was like, “My mum is asking me to be a bootlegger!”

My mum is really traditional. She always expected me to work in an office. The idea of a successful career was being a doctor or engineer. That was the standard. But a few years ago I invited her to see me perform. She said, “I don’t know what you are doing, but that looks… very nice.”

Now I make up one half of Syndicate, a freeform audio-visual collective consisting of DJs, producers, and visual artists. We started out about five years ago. Back then, the club scene was very housey, but it gave us a space to experiment. We didn’t have funding, so we’d go out and make things ourselves. We used white Ikea curtains stretched over wooden frames as projector screens. Now, we tend to sound more experimental and have a strong performative element.

“My mum said, ‘I don’t know what you are doing, but that looks… very nice.’”—Cherry Chan

We have a word in Singapore called “kampung,” it literally means “small village” and it describes the scene here. You’re friendly, you support each other, and you play at each other’s nights. We like each other’s eccentricities. Our friends NADA are a two-piece outfit, and the guy paints his face all-white and mixes Malay cultural music. There’s a lot of mixing Malay, Chinese, and Tamil culture with the global music scene.

I grew up in Taman Jurong, and I remember my mother would watch a lot of Chinese drama with characters like Teresa Teng, who is a very classic Chinese singer. My mother usually likes Mandarin music, but I made a downtempo mixtape and a dub and reggae mixtape for her, and she actually preferred the dub one! I was like, “Don’t you like the one with more singing on it?” And she said, “No, I like this one because when I’m driving I can bop my head to it.”

I identify as a third generation Singaporean, but my grandmother was five when she was sold here as a child bride from China. Can you believe that? Maybe there’s a link to me wanting to celebrate girls now. The older generations have so many stories to tell; ours tend to let the music do the talking for us.

As told to Kieran Yates