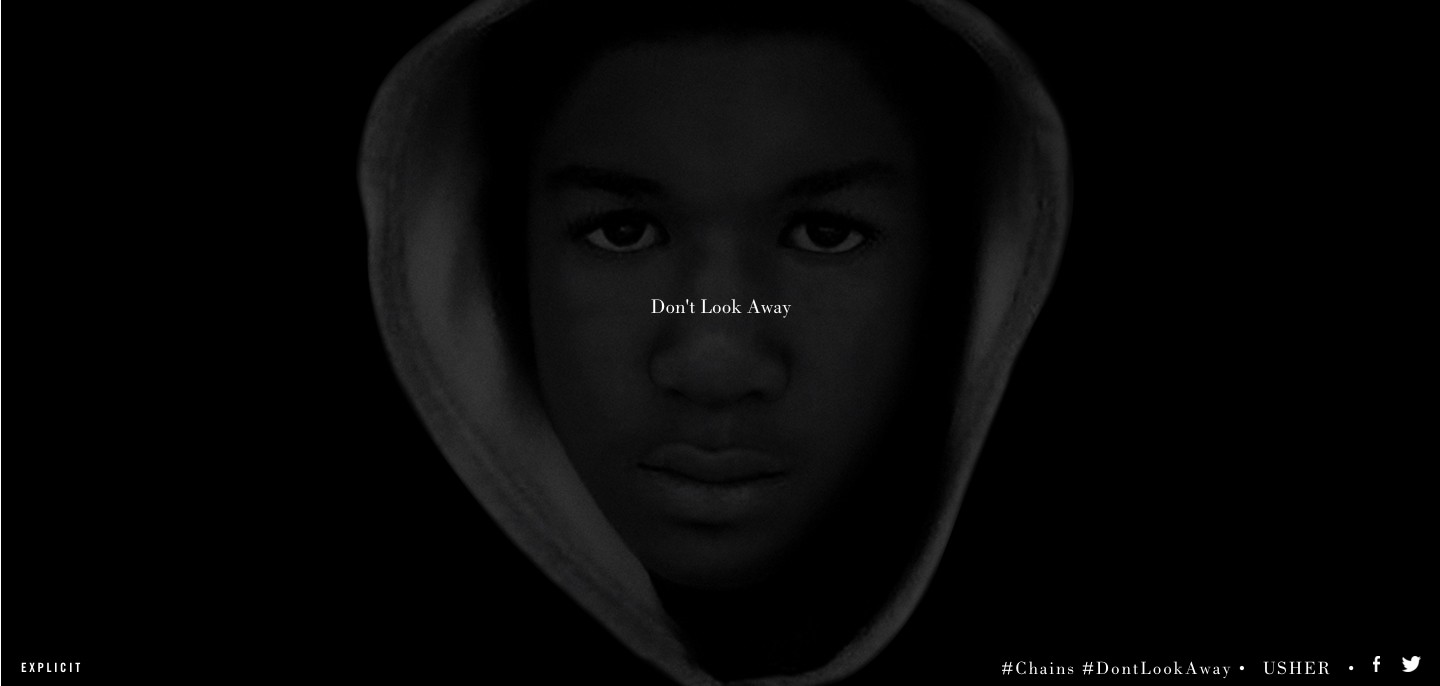

In October, Usher released a single called “Chains.” It was accompanied by a browser-based interactive video created in collaboration with the artist Daniel Arsham, hosted by TIDAL, and promoted under the hashtag #DontLookAway. Like the song’s lyrics, the visual implores the viewer to acknowledge a few of the black men and women killed or otherwise targeted for their race in recent years; the viewer must lock eyes with black and white photos of the deceased to unlock the track. If you avert your gaze at any point or lean too deeply out of the view of your computer, the webcam-enabled technology pauses and begs you not to look away. “While racial injustice keeps killing, society keeps looking away,” an introductory title screen reads.

The first time I watched it, I lasted just two dead faces. When I felt uncomfortable, I closed the tab, a privilege admittedly reserved for the living. On the morning of the video’s release, I had a short conversation with a co-worker about the unlikeliness of Usher releasing such a politically motivated piece of art. Over his impressive, damn-near unprecedented two-decade-long career, Usher has been known for many things—a strong voice, phenomenal dancing, symmetrical dimples—but his political messages have largely been restricted to social media, occasional press interactions, and, presumably, his personal life. This song marked new territory for him, hinting at an attempt to, at best, use his influence for good or, at worst, take advantage of a new relationship between celebrities and the public that expects, or demands, social consciousness from even its poppiest of stars.

Given the current sociopolitical climate—where #BlackLivesMatters activists have been able to jostle presidential candidates to the left on race, and where corporations are increasingly fearful of being considered offensive on social media—it stands to follow that Usher was neither the first nor will he be the last to incorporate politics into his consumer-facing work. Earlier in the summer, Janelle Monae’s Wondaland camp, including Jidenna, Deep Cotton, and the band St. Beauty, dropped “Hell You Talmbout (Say Their Names).” It’s a protest song in the most literal sense possible. Over chanting drums, it calls out the names of victims of police or vigilante murder in remembrance, and was rolled out with a series of protests around the country led by the crew. They were alternately lauded and mocked; some internet commenters, myself included, called bullshit on the move. Not because it was difficult to believe their concern about racial justice in America, but because it read like a marketing meeting-hatched rollout wherein they wore social justice like a costume.

Imagine if Kanye West called out George W. Bush for not caring about black people in 2015. On social media, at least, he would likely have been treated more like a folk hero than an outlaw.

Wondaland’s intentions aside, the moment felt like the inevitable culmination of the newfound cool of social justice, a shift that has made it a marker of social capital, a performative way to make yourself desirable, whether as a brand or simply a person. Social justice issues are becoming widely understood; there is a political vocabulary that is infinitely more common now than it was even a couple of years ago. Language to describe the minutiae of racism, cultural appropriation, and rape culture has seeped from academia into the mainstream lexicon as a way of dissecting and, in theory, resolving social issues involving race, gender, sexuality, and more.

Writing in The Nation in 2014, Mychal Denzel Smith argued that the killing of Trayvon Martin by a self-appointed neighborhood watchman, and the lack of justice that followed, sparked a change in the consciousness of black people. “Trayvon’s death ignited something durable in a considerable number of black youth. Whatever apathy had existed before was replaced by the urge to act, to organize and to fight,” he wrote, pointing to a rise in youth activists and the establishment of more action-oriented organizing.

But if Trayvon Martin birthed a new generation of activists, the killing of Mike Brown two-and-a-half years later by a police officer gave rise to a new framework of politics for the contemporary era. Apathy, from anyone, became unacceptable. Brown’s death was not the first time the internet rallied around a social cause, but it was among the most visible. Speaking publicly became not the domain of radicals, but a necessary way to identify yourself on the political spectrum, a declaration that you were either with or against black people. Most intensely in the days that followed Brown’s shooting, but also in the year since, I have seen tweets, Facebook posts, Tumblr notes, and YouTube comments criticizing silence and equating it with indifference.

Not for the first time, but perhaps more intensely than ever before, celebrities like Beyoncé and Jay Z, Kim Kardashian and Miley Cyrus, were slammed for their silence. (The Knowles-Carters wound up attending a march and reportedly donating to the bail funds of anti-police-brutality protesters.) When J. Cole visited Ferguson soon after Brown’s death, he tried to do so quietly, with no press, conscious of the gesture looking like an empty publicity moment. Instead, he was turned into a hero by fans who admired his dedication to the cause. The sentiment went a long way toward bolstering his image and it’s not uncommon to hear people shout him out for it, even a year later.

Imagine if Kanye West called out George W. Bush for not caring about black people in 2015, as he had in that now-infamous 2005 telethon raising money for victims of Hurricane Katrina. On social media, at least, he would likely have been treated more like a folk hero than an outlaw. Gone are the days when celebrity’s political action is a concern for PR agents, a potential career-ender. In contrast the thread of Nina Simone’s difficult career, as suggested in the recent documentary What Happened, Miss Simone?, is that being outspoken about her political beliefs wound up ruining her life.

For lesser-known public figures, voicing their political beliefs, if they are the right ones, has become a surefire way to attract positive press. When actor Amandla Sternberg called out Kylie Jenner in a school assignment for what she described as appropriation on Jenner’s part, her profile rose. And when Zendaya wrote an open letter similarly criticizing Giuliana Rancic for racist language linking Zendaya’s red-carpet dreadlocks to weed, she was celebrated for it in a continuous stream of praise on social media and across the internet, where the persistent feedback loop of fandom can feel hollow and hyperbolic, even when it isn’t.

It’s easier than ever to say the right things and loudly criticize people who don’t, to the point where conversations about social justice have been co-opted by people who aren’t directly affected or for whom arriving at a true solution isn’t particularly urgent.

As social media turns everyone into a micro-celebrity with a platform, it’s especially significant that it isn’t just the rich and famous who are compelled to be vocal. More and more people online are adopting a new sociopolitical vocabulary and, with it, identity—and that’s a good thing. Consider, for instance, the concept of cultural appropriation. Until a few years ago, it was not widely known. Today, thanks to the work of many activists, including the academic Dr. Adrienne Keene, who runs the popular blog Native Appropriations, it has become a fixture in pop culture discourse. Flagrant missteps persist, but more members of the general public understand how, as Keene describes, wearing a headdress is rooted in, and works to reinforce, systemic power imbalances. Consider, too, the way the phrase “social justice warrior” began losing its snarky connotation, becoming an increasingly fringe insult deployed more by Reddit trolls than moderates eager to uphold the status quo.

However, if people increasingly use social justice as a tool through which to accumulate social clout, vying for their own place in the public eye, there will be dangers too. It’s easier than ever to say the right things and loudly criticize people who don’t, to the point where conversations about social justice have been co-opted by people who aren’t directly affected or for whom arriving at a true solution isn’t particularly urgent. We construct our best selves in public, using fragmented platforms like Snapchat, Twitter, and Instagram to project the identities we want. We are incentivized by the endorphin rush of retweets and double taps, with the added awareness that the stakes are higher as social media has become fully entrenched in modern life. Saying the right thing can make or break you, encouraging us to act informally as own PR agents. But if our politics are driven by the urge to be considered kind rather than the urge to actually be kind, social justice becomes like any trend, susceptible to fading out whenever the next good look comes along.