Googling “Zayn Malik’s house” brings up dozens of blog posts that show you what it looks like: a big white box with chrome accents evoking Miami Beach, even though it’s just down the road from a 12th-century church in a bedroom community north of London where, more than a young pop phenomenon, you’d expect to find the family of a middle manager in finance gathered around the TV watching The X Factor.

Zayn, 22, just returned to the United Kingdom after three months in Los Angeles, and as he sleeps off jet lag into the late afternoon, I wander around his gated property. In the driveway he’s collected all kinds of things with wheels: two big dirt bikes and a miniature one, a go kart adorned with a Z in the style of the Superman logo, a vintage Mini Cooper, and a few cars that are simply old, which he has spray-painted all over with lime green doodles. Street art, as any fan knows, is one of Zayn’s passions, and he has a room inside where he’s painted over every available surface.

These are the hobbies of a rich young man, but entering Zayn’s backyard stirs up an eerie feeling of boyhood bumping up against something darker. Boxed on his porch is a high-powered Predator CarbonLite crossbow. A rope bridge leads past graffitied plywood reading “Fuck this life” to a garden shed that’s been converted into a pirate-themed pub. Handwritten on the door are the bar’s “hours” (it never closes) and the message “I pissed inside.” The building appears to have been shot up by paintballs. On the far side of the yard is a 25-foot Native American teepee, like something out of Neverland. And dead center, at the focal point of all this, standing with its head wrenched back, is a fighting dummy—one of those big, muscly torsos that you can practice punching or, in Zayn’s case, fire into hundreds of times with arrows.

It’s been seven months since Zayn quit One Direction, one of the biggest bands in the world and his employer for five formative years. His house is a symbol of everything he achieved during that time—and his unease about those very same achievements. So far, Zayn’s has been a story about how your life gets boxed in by other people’s perceptions of you, and how easily that can spiral out of control. This happens to everyone, but in a famous boy band, the gulf between who you are and who the rest of the world thinks you are is tenfold. As the band’s only person of color, and the West’s single most prominent Muslim celebrity, Zayn has faced misunderstanding to an unimaginable degree.

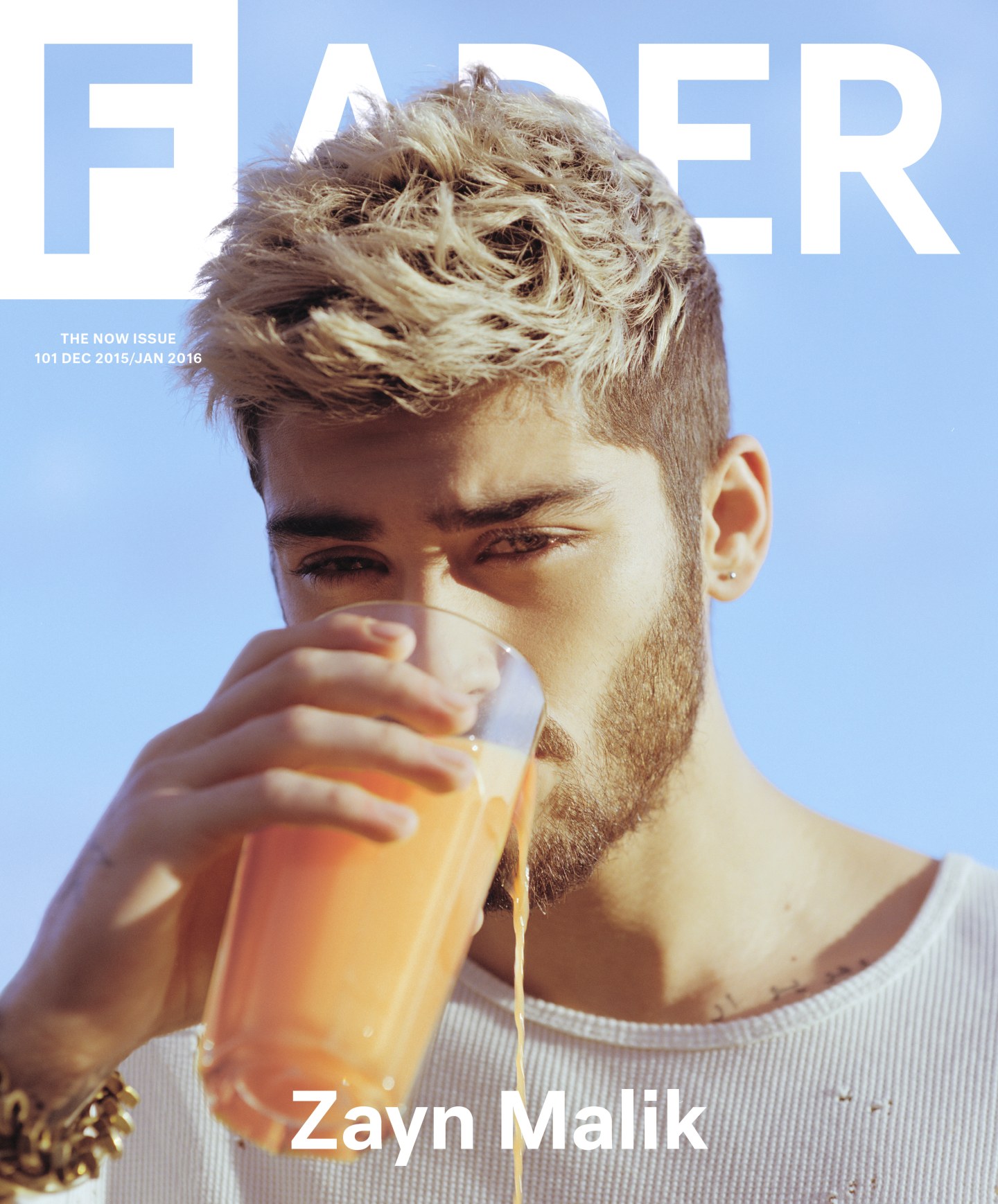

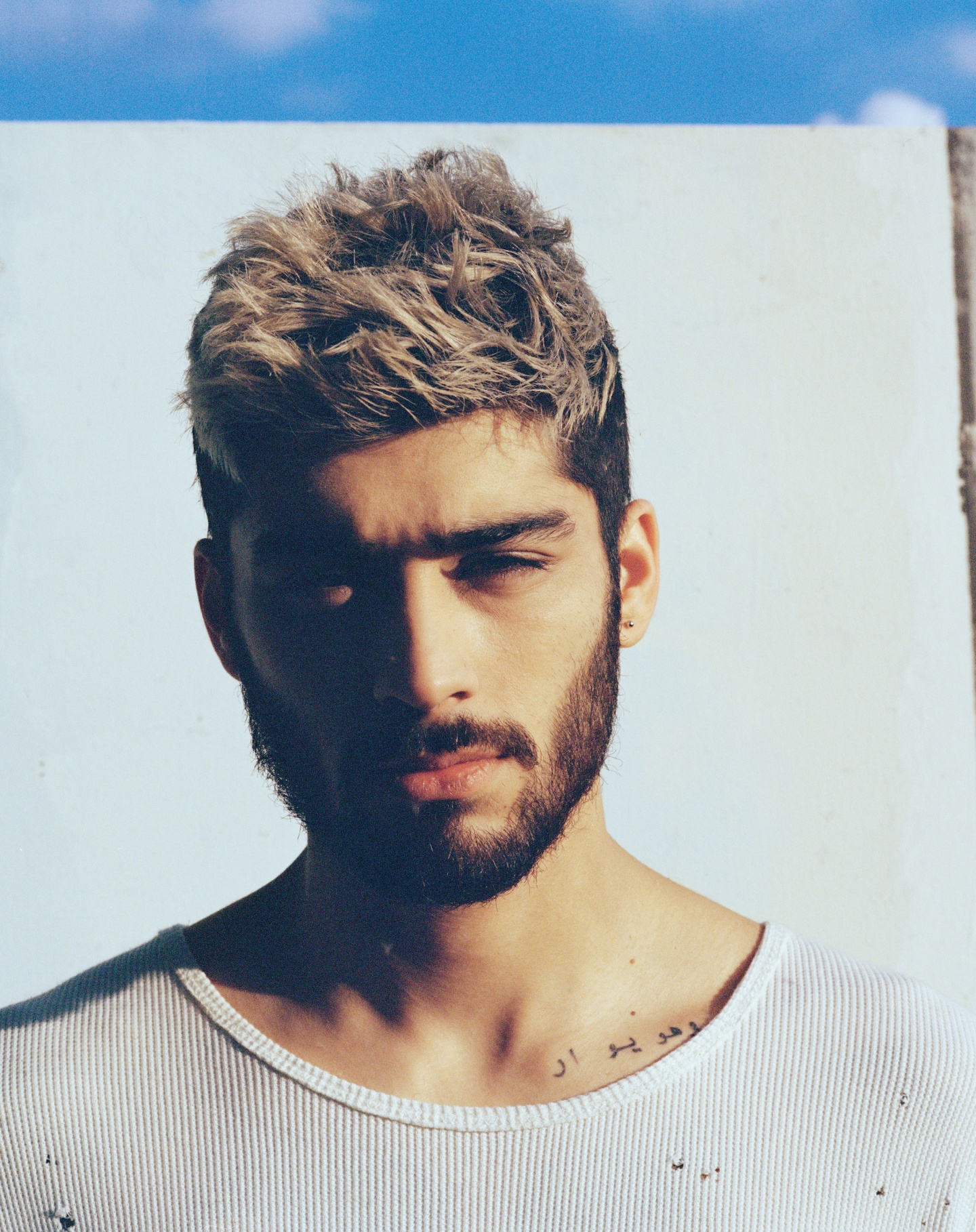

Posing on the seat of one of his motorcycles, Zayn shifts his bare abs to catch a fading sliver of light. He has stepped into this photoshoot straight after emerging from inside the house and distributing handshakes among a 12-person crew amassed around him. It reminds me of a scene from the 2013 documentary One Direction: This Is Us, where Zayn is awoken in the middle of the night because it’s his turn to hop in a booth and record. His professionalism, by now, is instinctive.

Zayn has been famous for a quarter of his short life, but the rest of the time was pretty modest. “This is my dream house,” he tells me, once the pictures are done. We’re settled into his backyard pub with some Beck’s, and he’s fired up a spliff. “The neighborhoods I came from were not like this.” He was born in a working-class neighborhood in Bradford, a city in northern England, and the influence on his accent is unmistakable: words turn sporadically melodic as every U and A is pronounced like an O. “The whole vibe of Bradford is influential,” he says. “It’s not the most funded place, in terms of the government, but there’s a lot of character there. There’s a lot of strong family values. Everybody’s very proud, and everybody’s stuck in their ways. That rubbed off on me a little bit and made me a stubborn person, and made me very aware of who I was. If you weren’t aware of that in Bradford, you kind of got left behind.”

The name Zayn Malik means “beautiful king” in Arabic. He has a Pakistani father named Yaser and an English mother named Tricia who converted to Islam to marry. “I’ve always tried to learn as much as I can about my husband’s religion and culture,” Tricia told the BBC in 2013. “I made sure the children went to the mosque. Zayn has read the Quran three times.” When he was growing up, she worked as a halal chef at a primary school, cooking meals for Muslim children.

In the summer of 2010, a 17-year-old Zayn traveled south to Manchester to audition for the seventh season of The X Factor. His try-out song was “Let Me Love You,” a 2004 hit by the R&B singer Mario. “My main influences in music came from my dad,” Zayn says now. “It was a lot of R&B, a lot of R. Kelly, a lot of Usher, a lot of Donell Jones, a lot of Prince. He used to play a lot of rap as well, 2Pac and Biggie. A lot of bop, a lot of reggae, Gregory Isaac and weird artists like Yellowman.”

While Zayn always imagined singing on the show, he wouldn’t have actually tried out if it weren’t for his mom. “People laugh at me because it sounds so childish now, but genuinely, at the time, I was a lazy teen. If I was in control of me going to audition for X Factor, I would have never gone because I would have never got up on the day of the audition at four in the morning. The reason I woke up is because my mom came in the room and was like, ‘You have to go audition for this show.’ I felt like I had to do it because I owed it to her.”

“Would you listen to One Direction, sat at a party with your girl? I wouldn’t. To me, that’s not an insult, that’s me as a 22-year-old man.”

He made the cut, but in the show’s televised “bootcamp” he exhibited a costly shyness about dancing and failed to qualify for the next round. But the judges made an unexpected offer: the chance for Zayn and four other boys who’d just been cut—Harry Styles, Liam Payne, Niall Horan, and Louis Tomlinson—to stay on together as a group. One Direction, a name Harry suggested, performed for the first time in an episode filmed at show producer and talent judge Simon Cowell’s palatial home in Spain, where they covered Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn”: Illusion never changed/ Into something real/ I’m wide awake and I can see/ The perfect sky is torn. Foreshadowing, perhaps.

When the group placed third on the show, Zayn winked into the camera and told the audience, “This isn’t the last of One Direction,” and, within the month, it was announced they’d signed a $3.1 million contract with Cowell’s label, Syco. One Direction released a platinum-selling album every November from 2011 to 2014. They were just the sixth act ever to debut their first four LPs at No. 1 in the U.S. and the first non-Americans to do so. In between albums, they toured the globe relentlessly, in 2014 pulling in $280 million in ticket sales alone. 1

A decade after *NSYNC broke up, One Direction invigorated the boy band model by injecting every calculated thing they did with a dose of genuine-seeming anarchy. Arena rock, it turns out, is an ideal style for average-to-good singers with gravity-defying hair who are either unwilling or too uncoordinated to follow conventional choreography. It looks more fun, anyway, to just jump around. The bandmates’ social lives were carefully confined, with the tabloid mania surrounding a leaked 2014 video in which Louis and Zayn smoke weed the rare exception that proves the rule. But in press appearances and performances, they seemed uncontrollable, just like you’d expect from five guys in their late teens and early 20s. They’d crack in-jokes and jostle one another, perpetually pumping each other up and egging each other on until, as if by magic, the occasion of song joined their voices in a single, pristine chord.

Boy bands like One Direction are unique in music because they intentionally and directly speak to a young, female audience. This is a lucrative approach—when mom or dad has to chaperone, it’s two concert tickets sold for every fan—that can also have a positive impact. In a convincing essay for Racked called “The Absolute Necessity of One Direction,” Alana Massey calls boy bands “a profound social good” because they present a gentleness that isn’t traditionally encouraged in young men, or so publicly and unabashedly demonstrated by them. Though their fans don’t all belong to any one age group or gender, a boy band’s classic structure—the cute one, the funny one, the bad boy, and so on—affords fans a chance, unlike in actual life, to fantasize without prejudice about which type of guy they’d like, or why, or how often they might switch allegiances. Massey calls this happy alternate reality “the Kingdom of the Girl,” a place where, for once, young women are wholly in power, being respected, celebrated, and adored. 2

Occasionally, spreading all this love can backfire. One of Zayn’s managers told me that Directioners have taken to ringing Zayn’s doorbell in the middle of the night, hoping he’ll think it’s an emergency, rustle out of bed, and stumble into conversation. But when I slip up in describing this type of behavior as “crazy,” Zayn corrects me to say his fans are just “passionate.” Perhaps he’s weary of their real, threatening power over his life—he keeps security guards and an attack dog for a pet—or perhaps he’s acknowledging their tastes as legitimate, a subtle feminist gesture. I’m inclined to think it’s the latter, because loving One Direction is a perfectly rational thing to do. In a world that is by nobody’s standards ideal, their finely tuned pop songs of unfailing love are a welcome relief. It’s only sensible for fans to recognize what brings them joy and grab onto it tight.

Some of Zayn’s biggest supporters are fellow people of South Asian descent, many of whom see him as a powerful representative of their culture—or at least someone whose stardom and visibility raises important questions. In a 2015 essay for Noisey, Diyana Noory says that One Direction caused some people in her community to discuss what it means to be Muslim in a new way. “Zayn has found himself standing in for the world’s questions like a modern prophet,” she writes. “Can you drink, smoke, and sport tattoos while calling yourself a Muslim? Is music haram [sinful]?” One of Zayn’s most routinely insightful chroniclers is Two Brown Girls, a pop culture podcast hosted by two writers, Montreal’s Fariha Róisín and New York’s Zeba Blay. In one 2015 episode, Róisín says that even Zayn’s small gestures, like his annual tweet wishing “Eid Mubarak,” have meant a lot to her as someone trying to balance religious tradition and secular interests. “You’re either fully committed, and that’s great and beautiful, or you’re an atheist and don’t give a shit,” she said. “I’ve never been either of those two things, and I think Zayn is similar to me in that sense.” In our interview, I read him her quote.

“I always felt that I got some favoritism sometimes in certain places because the fans obviously want to relate to someone that’s similar to them,” he says, having consumed the spliff and moved on to a cigarette. “I’m just a normal person as well as following my religion, and doing all the normal things that everybody else does. I love music and I get tattoos and I make mistakes, and I’ve had to go through relationships and break up relationships. I feel proud that people actually look to me and can see themselves in that.” I ask if that attention makes him feel pressure to set a good example, and Zayn replies, “I don’t feel like I felt pressure ever. I always felt good that I was, like, first of my kind in what I was doing. I enjoyed that I brought the diversity. But I would never be trying to influence anything or try to stamp myself as a religious statement or portrayal of anything. I am me. I’m just doing me.”

Some people have expressed hope that leaving One Direction would embolden Zayn to talk more about political issues, like Islamophobia in the West, but he doesn’t seem driven to. Maybe that’s because over the past five years he’s been accused, both seriously and satirically, of causing 9/11, joining ISIS, and recruiting fans to wage jihad, or because people threatened to kill him after he tweeted #FreePalestine. I ask him if harassment is a deterrent to speaking out. “It’s not even the harassment,” he says. “I just don’t want to be influential in that sense.” Still, after hearing Zayn talk about how normal he is, I can’t help but wonder how “normal” a Muslim person would have to be in order to appease all the world’s bigots—and whether, given the impossible degree of nonthreatening-ness that seems required, how someone in Zayn’s position could ever feel safe enough to say something like, “Yes, I do want to be influential.”

One of the stranger things putting pressure on Zayn and the current members of One Direction involves “shipping”—short for “relationshipping”—a short fiction genre that imagines celebrities in relationships with each other. In the case of the band, that often means matching the bandmates up with one another. Just as stereotypical boy band personas encourage fans to fantasize, shipping affords its pseudonymous authors the chance to explore their own sexuality in a safe environment. It’s the rare unorchestrated, participatory byproduct of One Direction that costs nothing to fans. Some shippers take things a step further, however, compiling meticulous research—footage of a clutched elbow in an interview, GIFs of lingering glances at a show—in an attempt to prove that their fiction is based in reality. They become amateur sleuths, mining subtext deep in the singers’ private lives in order to secure their place as insiders, and prove they’re the band’s #1 fan.

The more intrusive fan theories are premised on the idea that One Direction’s management is callously covering up relationships—so I ask Zayn, who has new management now and can presumably speak more freely, whether any of the stories are true. Basically, he says, knowing that everything you do will be parsed for subtext is a terrible mindfuck. “There’s no secret relationships going on with any of the band members,” he explains. “It’s not funny, and it still continues to be quite hard for them. They won’t naturally go put their arm around each other because they’re conscious of this thing that’s going on, which is not even true. They won’t do that natural behavior. But it’s just the way the fans are. They’re so passionate, and once they get their head around an idea, that’s the way it is regardless of anything. If it wasn’t for that passionate, like, almost obsession, then we wouldn’t have the success that we had.”

Once you erase the line between reality and fantasy, you can’t really go back. A diehard believer of One Direction’s forbidden romances, for instance, could easily invent explanations for Zayn’s denial: Oh, he must have signed a nondisclosure agreement, or, The bosses must have some real dirt on him. This is how One Direction can become, for fans and casual onlookers alike, not just a band but an unsolvable puzzle. Even benign subjects like how Zayn became known as “the mysterious one” raise endless questions. Did he appear mysterious because management forced him to play that role—and if they did, was Zayn seen as mysterious because of the color of his skin? Or was he naturally withholding because he felt creatively exiled within the group? Or was it simply because on a few unlucky press days he just didn’t feel like talking? Zayn says there were plenty of times where an interviewer, having only asked questions of his bandmates, would turn to him and suggest, “Zayn you’ve been awfully quiet.” “I’m actually quite easy, a happy-go-lucky sort of guy,” he says, “but there was a lot of situations that were almost created to make me be portrayed as the mysterious or quiet one. I guess that’s just something that people buy into, and it helps them sell things. It’s a product that’s already designed, and it sells.”

Zayn has always had to navigate on someone else’s course, whether it’s regarding passionate fans or the way he expresses his heritage. But nowhere did that bother him so much as with the actual music, the reason for all of this. Yet again, the rules weren’t up to him. “There was never any room for me to experiment creatively in the band,” he says. “If I would sing a hook or a verse slightly R&B, or slightly myself, it would always be recorded 50 times until there was a straight version that was pop, generic as fuck, so they could use that version. Whenever I would suggest something, it was like it didn’t fit us. There was just a general conception that the management already had of what they want for the band, and I just wasn’t convinced with what we were selling. I wasn’t 100 percent behind the music. It wasn’t me. It was music that was already given to us, and we were told this is what is going to sell to these people. As much as we were the biggest, most famous boy band in the world, it felt weird. We were told to be happy about something that we weren’t happy about.”

“By the time I decided to go, it just felt right on that day. I woke up on that morning, if I’m being completely honest with you, and was like, ‘I need to go home. I just need to be me now, because I’ve had enough.’”

And so he quit. It happened in March 2015, but the exact timeline of his decision is hard to explain— Zayn says there was no one incident that led to his departure. “I guess I just wanted to go home from the beginning,” he says. “I was always thinking it. I just didn’t know when I was going to do it. Then by the time I decided to go, it just felt right on that day. I woke up on that morning, if I’m being completely honest with you, and was like, ‘I need to go home. I just need to be me now, because I’ve had enough.’ I was with my little cousin at the time—we were sat in the hotel room—and I was just, ‘Should I go home?’ And he was like, ‘If you want to go home, let’s go home.’ So we left.”

In the tabloids, a more scandalous narrative was presented. For almost the entirety of Zayn’s time in One Direction, he was dating—then engaged to—Perrie Edwards, a fellow The X Factor alum and a Syco signee to boot. In early March, Zayn was photographed at a Thai nightclub holding hands with a woman named Lauren Richardson, setting off a wave of cheating rumors. Though Richardson, who would go on to star in a reality TV dating show, told The Daily Star, “It was just an innocent picture. Nothing else happened,” another British tabloid, The Sun, featured an interview with another woman, a Swedish model, who claimed to have slept with Zayn that same night. Days later, on March 18th, Zayn played what would be his final One Direction show. A shaky video filmed from the crowd appears to show him briefly in tears. The following morning, after a Philippines immigration office demanded the payment of a “drugs bond” stemming from the leaked weed video, a One Direction spokesman announced that Zayn was taking a break from tour due to stress. Within a week, an official statement of his resignation was posted on the band’s Facebook page, with Zayn citing a desire “to be a normal 22-year-old who is able to relax and have some private time out of the spotlight.”

Did the cheating rumors affect his decision to leave? “The two things never really coincided in my mind,” he says. “Obviously, publicly, that’s the way it worked, because it worked well for the purpose. Them two stories looked good together side by side. Stories came out because we were in Thailand, and we were out and about. If we were out in Australia, if we were out in India, the same thing would have happened. It was just at a peak where the fame was intrusive and invasive. It wasn’t because of that that I left—that was just a contributing factor to everything. I’d already made my mind up before that.” 3

In August, five months after he left the band, news broke that Zayn and Perrie had called off their engagement. In a widely circulated story, The Sun claimed he dumped her via text message. Zayn takes the opportunity of our interview to deny this. “If you could word it exactly this way, I’d be very appreciative,” he says. “I have more respect for Perrie than to end anything over text message. I love her a lot, and I always will, and I would never end our relationship over four years like that. She knows that, I know that, and the public should know that as well. I don’t want to explain why or what I did, I just want the public to know I didn’t do that.”

These days, Zayn seems to be enjoying single life. A recent Instagram he posted of himself, shirtless and hugging an unnamed woman, set off a mad dash to find her identity. When I suggest he’s intentionally baiting people, his eyes light up with mischievous glee. The young man who left home at 17 is now, for the first time in his life, directing his own narrative and taking little chances to dirty it up. He’s smoking more and sleeping in. What he’ll make of his new circumstances is still an open question, and it won’t have a simple answer.

In late July, a week before Zayn’s breakup with Perrie became public, he signed as a solo artist to RCA, home to Chris Brown and America’s most beloved ex-boy bander, Justin Timberlake. Like Syco, the label is a subsidiary of Sony, and Simon Cowell reportedly helped broker the smooth transition—a fitting goodbye that presumably paid both men handsomely.

Shortly after a dinner of fish and chips, ordered in and consumed straight from cardboard containers on the back patio, Zayn and I are joined by James “Malay” Ho, the 37-year-old producer who’s become his main musical collaborator. Malay has just flown in from L.A. When asked if he’ll pose for a photo, he jokes, “Can you make me lose 30 pounds?”

Zayn’s first recording session after going solo was with Naughty Boy, a British producer with whom he had a public falling-out after a Rae Sremmurd cover they did together leaked in July. (Naughty Boy declined to comment.) In L.A., Zayn first worked with two British brothers, Michael and Anthony Hannides, but things only really clicked when he met Malay. He has a long list of credits for the likes of 50 Cent and John Legend, but is best known for executive producing Frank Ocean’s debut album, Channel Orange. (He’s also working on that album’s follow-up.) It’s Ocean’s sort of confessional, artisanal R&B that Zayn seems to want for himself, offering a return to his roots and the chance to be heralded as a true creative, rather than as an actor playing the part of one. Malay, who prides himself on facilitating an artist’s vision rather than injecting any signature sound, appears to be an ideal collaborator. Coincidentally, as the producer points out over the phone a week later, they also share a common upbringing: “We both have Asian dads and Caucasian mothers.”

Zayn got a few songwriting credits with One Direction, mostly for minor contributions to existing songs, but he says he spent countless nights writing on a laptop and guitar: “That was my therapy, like outside of the band.” Fittingly, his recording sessions with Malay have been private and low-key, happening far from what Zayn calls “the circus of Los Angeles studios.” Malay likes to use a mobile recording rig, and though it was unfortunately held up at customs for this trip, they’ve made good use of it in The Beverly Hills Hotel, in Zayn’s house in Bel-Air, and even out camping. That’s where Zayn got into archery, shooting at trees in the downtime while their generator regained electricity, and it’s where they laid down some of their favorite vocal tracks, backed by the soft hum of the woods.

These recording sessions will all go to Zayn’s forthcoming solo debut, planned for release in early 2016. Of the roughly 20 percent of the album that Malay estimates they recorded in a proper studio, even those parts were unconventional, like the time they rented a studio in The Palms Casino in Las Vegas after a night on the town. That’s how Zayn, who is doing all of the album’s writing himself, got the idea for a song. “We were sitting in the club,” Malay remembers, “and he was just like, ‘This situation, me in Vegas, I’ve done this before a million times, like all over the world, but not like this.’ It was a super simple concept, but that perspective comes from what he experienced at such a young age.”

Everyone moves to the pub, and Zayn takes much delight in filling drink requests. Malay connects his laptop to a single Yamaha speaker and cues up new versions of a few tracks, including the one they started in the Palms, which still needs a name. There’s a muted guitar line that sounds like something from The xx, but Zayn’s vocal parts hew closer to Miguel or The Weeknd—mid-range R&B with a distinct awareness of its own head-nodding flow, before letting loose for 10 straight seconds of Zayn’s incomparable falsetto.

The next song they play is an upbeat jam tentatively called “I Got Mine,” with freshly recorded trumpets and a beat that’s almost U.K. garage. The lyrics were inspired by a Guitar Center employee who struck up a conversation with Zayn about his Prince T-shirt, then revealed that he’d loaned his MIDI keyboard to Madonna’s touring band. “There’s so many people in L.A. that have a story to tell, but they never got to tell the story,” Zayn remembers thinking. “Every line in the pre [-chorus] of that song is a different person’s perspective. So, it’s like, Talk is cheap but we still talk it/ Road is far but we still walk it/ Writing chalks or change the story. At that point, that could be like a teacher writing on the chalkboard, writing a story, but they can change it. Keep it moving when it’s boring. The dustbin man, putting the garbage out, whatever. Thoughts come out just like they’re pouring. An alcoholic guy who’s, like, a super creative dude. It was all different perspectives.” He says that other songs on the album follow a similar approach—Zayn using his position to give voice to others—including one called “My Ways” that’s sung from his father’s perspective.

“People like Frank [Ocean], who have been in studios for years and years and years developing skills as songwriters—he’s been doing that on the performance side,” Malay says of their easy time working together, with most vocals recorded in just a few takes. “That’s powerful right there. His 10,000 hours or whatever have been invested as a performer. He has the tools physically and mentally to deliver at the drop of the hat.” Though actually writing and recording his own songs is new for Zayn, he’s feeling very comfortable. “It’s not hard,” he says. “To me, it’s like I stood in front of a canvas for about five years, and someone said like, ‘You’re not allowed to paint on this canvas.’ I’ve got the paint, I’ve got the fucking brushes, and I can’t get it on there. Now someone removed the plastic and was like, ‘Alright, you can now paint.’”

While the plastic may be off, saying goodbye to One Direction’s billion-dollar brand and global fan base means that as a solo act, Zayn will likely reach a significantly smaller audience. “A big part of why I left the band is I made the realization that it wasn’t actually about [being the biggest] anymore,” he says, unconcerned. “It wasn’t about the amount of ticket sales that I get. It was more about the people that I reach. I want to reach them in the right way, and I want them to believe what I’m saying. I’ve done enough in terms of financial backing for me to live comfortably. I just want to make music now. If people want to listen to that, then I’m happy. If they don’t want to listen to it, then don’t fucking listen to it. I’m cool with that too. I’ve got enough. I don’t need you to buy it on a mass scale for me to feel satisfied.”

“I can map every lyric and every note to mean something to me. It’s a snapshot of my life and the thoughts on my life, my hopes, my aspirations, and my regrets in the summer of 2015.”

In the aforementioned documentary that shows Zayn waking up in the middle of the night to record, cameras follow his mother as she comes home, for the first time, to a new house that Zayn bought for his family. He tells me that this single purchase was his only goal in the band, ever since his days on The X Factor. “In whatever way I can help them right now, because I’ve been almost gifted in a way, I do,” he says. “I feel like it’s my responsibility.” The cousin who was with him on the morning of his departure from the band—after realizing how far behind Bradford’s educational system was, Zayn paid to enroll him in private school in London.

As much as he says he was tired of the lifestyle that accompanies mega-fame, Zayn is working around the clock on his solo album—including taking time for this story, long after the sun’s gone down. “I’m working every day now, but I’m working on music that I enjoy,” he says. Were there any parts of One Direction’s music that he enjoyed? He says that’s beside the point. “That’s not music that I would listen to. Would you listen to One Direction, sat at a party with your girl? I wouldn’t. To me, that’s not an insult, that’s me as a 22-year-old man. As much as I was in that band, and I loved everything that we did, that’s not music that I would listen to. I don’t think that’s an offensive statement to make. That’s just not who I am. If I was sat at a dinner date with a girl, I would play some cool shit, you know what I mean? I want to make music that I think is cool shit. I don’t think that’s too much to ask for.”

That’s not to say that he’ll never work with his former bandmates again. In old interviews and even in the note announcing he was quitting, Zayn always expressed a desire to remain “friends for life” with his former bandmates. So it was surprising when only weeks after his exit he got into an argument on Twitter with Louis over someone’s poor choice of a photo filter. I ask him where he and the group stand now. “I spoke to Liam about two weeks ago,” Zayn says. “It was the first time I’d spoken to him since I left the band, and I rung him, and he wanted to talk. He said that he didn’t understand it at the time, but he now fully gets why I had to do what I did. He understands that it’s my thing, that I had to do that, and that basically he wants to meet up and sit down and have a good chat in person, and he wants to do some music and work on some stuff aside from being in the band, which we always wanted to do anyway.”

You can bracket phases in Zayn’s life by albums and concerts and scandals and hairstyles—after quitting the band, he sported a penitential buzz cut. Now, liberated from the band and out of the relationship he’d been in for almost as long, his next phase will be defined not by any clear direction but by the total absence of one. He’ll try new, weird things and see what fits, then maybe throw it all out again. Maybe in a few years the fame he says he’s rejecting will be exactly what he wants. The point is it’s up to him. “When an album comes out, it’s a snapshot of the artist’s life,” Malay tells me. “‘This is who I am, this is where I’m at, fuck with me or don’t fuck with me.’ It takes a lot of guts to do that. I’m sure in the future he’s going to have a whole new set of things he’s dealing with. This particular piece is definitely dealing with a transitional point in his life, but I don’t think there’s an end to that.”

Zayn does seem up-in-the-air about where exactly he’s going, and a bit cagey too. “The album—I have a name for it in my head right now, but I don’t want to tell you what the album name is—all the songs are different genres,” he says. “They don’t really fit a specific type of music. They’re not like, ‘This is funk, this is soul, this is upbeat, this is a dance tune.’ Nothing is like that. I don’t really know what my style is yet. I’m kind of just showing what my influences are. Depending on what the reaction is, then I’ll go somewhere with that. If people like that I’m a bit more R&B, then I’ll do more R&B on my next album. If they like the fact that there’s reggae on there, I might do more reggae. It’s just depending on what they want and what I feel comfortable with at the time. I might even have a rock tune on the album, but it’s kind of like R&B-rock.”

A week later, Zayn sends me a three-paragraph mission statement for the album that elaborates on his feelings. The very fact of this letter’s existence says a lot about his intentions. “I can map every lyric and every note to mean something to me,” it says. “It’s a snapshot of my life and the thoughts on my life, my hopes, my aspirations, and my regrets in the summer of 2015.” The last part is what really clicks for me—it’s just this summer. The years that came before, and whatever comes after, can stay a mystery. That’s how everyone lives, isn’t it? You find your way. Where Zayn’s entire identity was once fixed awkwardly upon him by others, he’s now embracing a perpetual state of becoming something else, recognizing he’s changing as he goes: this is me, trying now, and it won’t be me forever.

Back in the pub, Zayn describes his dad as a way to underscore his own change. “My dad is super reserved, and he kind of just is the way that he is,” he says. “He just stays in Bradford. He’s really shy, and he doesn’t like to be in the limelight. He kind of feels like I just went and auditioned and never came back.” This idea—what happened to the families when their boys left—has been stuck in my head since 2013, when One Direction put out a strange video for “Story of My Life.”

The video shows actual photographs of the bandmates as kids with their families, then, in a trick of special effects, morphs everyone into their present selves. The One Direction boys are free to move around the frame, browsing an old childhood bookshelf or looking wistfully out the bedroom window where they once projected so many dreams, but their family members—played by their actual family members—remain frozen in place. It’s as if celebrity brought the band immortality, but it robbed them of the ability to connect with the ones they most deeply love.

Now Zayn has chosen another path, leaving the world of gods to live a more fallible life. There’s something really sad about that—the once mighty band feels a little off balance, and solitary Zayn can seem so lonely in comparison. But he isn’t alone. Fifteen minutes before our interview ends, one of his managers pops in to tell Zayn his mother has arrived. She’s driven down from Bradford, and when he’s done with work tonight they’ll head home together, spend time as a family, and probably not worry about what comes next.

1. One Direction’s fifth album, Made in the A.M.—which some fans believe stands for After Malik—was released in November 2015. But a sixth LP won’t be coming next year: in August, it was announced that the four remaining members would break for an extended hiatus in 2016.↩

2. That’s not to say One Direction’s music has always been understood as empowering for women. It’s been widely noted that their debut single, “What Makes You Beautiful,” reinforces an out-of-whack power dynamic where women are expected to feel unsure of themselves until they receive compliments from men. But, to the band’s credit, no song since has been quite so insensitive.↩

3. There is, unsurprisingly, a conspiracy theory among some fans that hypothesizes that Zayn’s exit was decided months in advance, though the evidence is a bit shaky. In June 2015, two months after Zayn left the group, One Direction released an ad on YouTube for their Between Us fragrance that starred only the four remaining members—however, judging by the absence of Harry’s mermaid tattoo, which he got in November 2014, the footage must have been shot when Zayn was still in the group. Why would they have filmed a group hug without him? November is also when Zayn missed his first concert date, in Florida, as well as a subsequent interview on The Today Show, which prompted Matt Lauer to suggest, on the air, that Zayn was having issues with substance abuse. This was a claim that the band, and Zayn, vehemently denied, blaming a stomach bug instead.↩

Pre-order a copy of Zayn Malik's issue of The FADER now, or buy it on newsstands December 15.

Styling by Jason Rembert and Caroline Watson. Makeup by Gemma Wheatcroft.