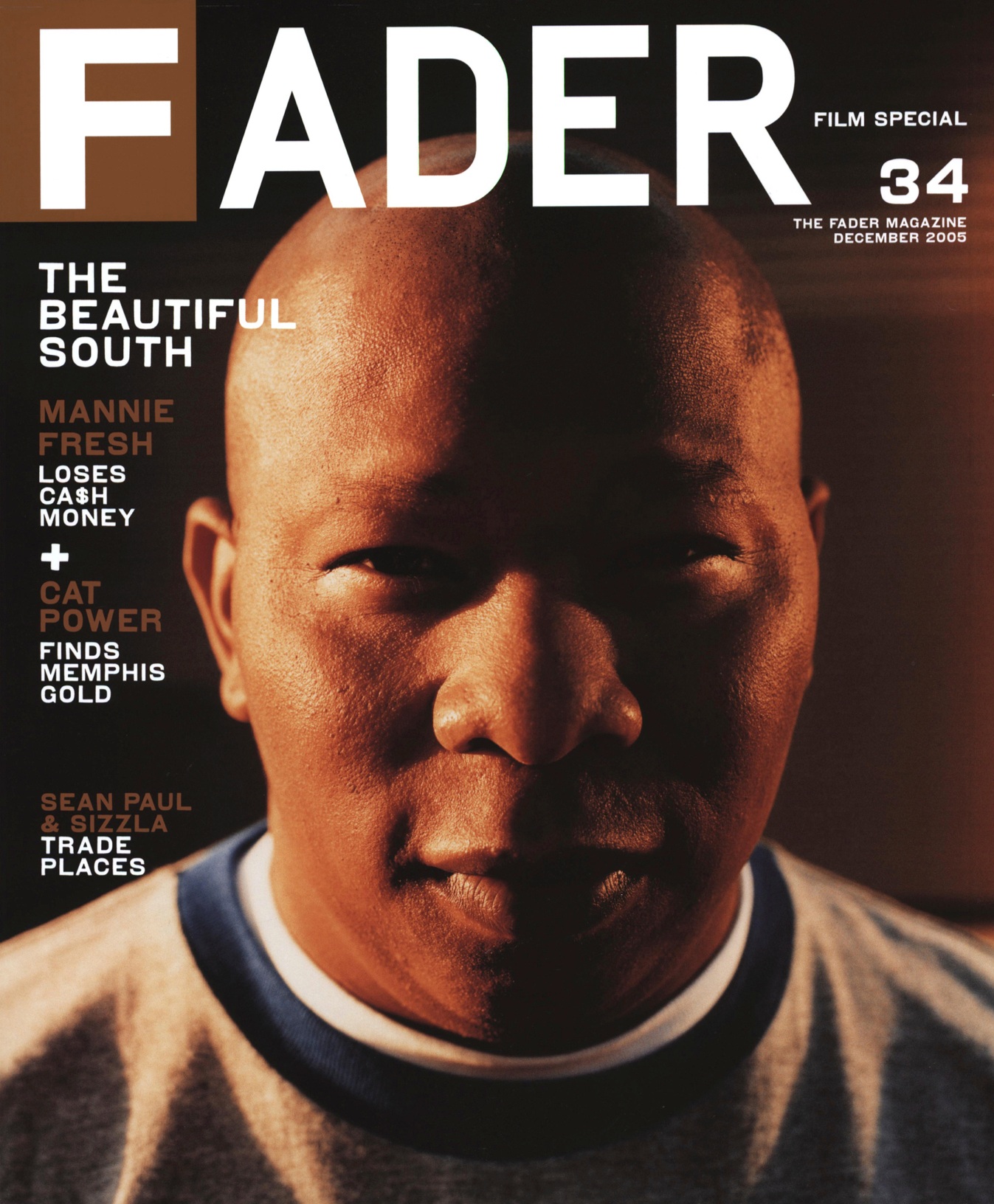

In Mannie Fresh’s 2005 Cover Story, The Super-Producer Finds Freedom After Cash Money

Online for the first time, this story chronicles Fresh’s split with the label that “put the business into rap,” and his relationship with New Orleans, post-Katrina.

In 2005, Will Welch, The FADER's editor at the time, interviewed super-producer Mannie Fresh for our 34th issue—Fresh's first ever cover.

Young Jeezy, the Atlanta-based rapper who released his debut album this summer, had a pretty substantial hit with the catchy BOOM-BOOM-CLAP and hustle talk of his single “And Then What.” But unless you copped the album or its bootleg, chances are the version you heard time and again on the radio, on the TV and in the club was without the spoken introduction by Mannie Fresh, the man who produced the song. Niggas, bitches, bitch-ass niggas, dyke-ass hoes, black-ass and bright-ass hoes! Fresh calls out from the mic as soon as the beak kicks off. Fags, hags, and scallywags! Get y’all motherfuckin ass on the floor ya heard?! Its about to go down like a motherfuckin plane crash! Its about to burn like a bad-ass perm!

The first time you experience one of those Mannie Fresh introductions is kind of like the first time you experience one of his patented snare rolls—a genuine What the FUCK?! moment. On songs from the last couple months by everyone from TI to Jeezy to Trina to Slim Thug, Fresh has kicked things off by shouting out ladies, gentlemen, bad-ass babies, crackers, gays, rednecks, coloreds, ducks, chickens, mammals, cats, dogs, Valujet, bad mamba-jambas and “all that in-between.” It is a quirky, unhinged, awesome, absurd, populist, hilarious, and confusing trademark that is ultimately irresistible, but also kind of inspiring. Mannie Fresh himself, of course, claims that his intros are something that just fell out his head one day, and while that’s probably true, they also intimate a lot more about him.

“The Cash Money sound pretty much changed the era. It kind of put the business into rap. It was like, ‘Get your money, dude. This is a billion dollar business.’”—Mannie Fresh

Fresh is associated first and foremost with Cash Money Records out of New Orleans, Louisiana. Cash Money is mostly broadly famous for coining the term “bling,” which holds the dubious claim of being perhaps the most persistent bit of slanguage to jump from hip-hop into the mainstream. Although Cash Money is also remembered as the sound of 1998, it was formed in the early ‘90s when Baby and Slim Williams—a pair of brothers from the Northside of New Orleans—hollered at Fresh—an already establish DJ and producer who hails from the Southside—about starting a music venture. “Cash Money was a group, not even a label,” Fresh says of the crew’s beginnings. “It was just Brian [Baby] and Ronald [Slim] coming to me, saying, “We want to start a record company.’ And I was saying to them as some street dudes, ‘If y’all really want to do this dude, it's either the streets or this.’ And they were like, 'We really believe in it.' So it was me—my ideas or whatever—and them funding it, and from there it went crazy.”

The word “crazy” is as overused in and around hip-hop this year as “incredible” was last year, but in this case its no exaggeration. According to Fresh, the label released an album by Juvenile that sold 495,000 copies around the South completely independently. The follow up release by the Big Tymers (Mannie Fresh and Baby) sold, according to Fresh, around 400,000 units. “When the major label deal first happened, everybody was like, ‘Why they gave them so much money?” Mannie recalls of Cash Money’s deal with Universal Records. “But we were doing close to gold independently so if the offer was mediocre it was like, ‘Yeah, we don’t need it.’” Eventually the Williams brothers came to a $30M agreement with Universal and a new era in hip-hop was minted. At the time, many critics complained about the outlandish materialism of Cash Money’s lyrics, and even as the label’s records sold and sold, outsiders wrote the crew off as a fad—a temporary empire built on the shifty sands of hyperbole. But not only did those critics fail to recognize the potential for longevity in the music—especially in the Mannie Fresh beats—but also what was being called hyperbole soon proved to be, in some sense, a reflection of a new truth. Over-the-top materialism had been a part of hip-hop for years, but Cash Money ramped up the values of its signifiers according to just how lucrative the industry had become. The cover of one of Big Tymers album sports a photo of Fresh and Baby wearing pounds of gaudy jewelry while sitting at a table that is likewise covered in iced-out watches and chains. The message is clear—We can't even wear all this shit!!!—and the label posted the album sales to back it up. “The Cash Money sound pretty much changed the era,” Fresh says without hesitation. “It kind of put the business into rap. It was like, ‘Get your money, dude. This is a billion dollar business.’”

“A lot of artists are scared when they see trumpet players show up—they like ‘Nah that ain’t what I want.’”—Mannie Fresh

Of course the reason Mannie Fresh is all over radio right now, on songs with artist signed to a variety of labels, is because he is no longer with Cash Money Records. After years spent defining and developing the next-level New Orleans bounce sound of one specific crew (he produced every single golden-era Cash Money song), Fresh has gone solo and opened himself up for business, going wherever the paycheck takes him—Atlanta, Houston, Miami, Los Angeles, New York, wherever. As the conversation about the details of his situation at Cash Money develops, it becomes clear that the Williams brothers kept white-knuckle tight reigns on the architect of their sound, making sure the sound was just that—theirs.

“Last year at a DJ seminar I bumped into people from Interscope,” Fresh recalls. “They were like, ‘Dude, Mannie, we wanted you to do a song on the Game album and we know your schedule was too busy but hopefully we gonna get you on the next one.’ So I’m like, ‘Wow. I never knew y'all was trynna get in touch with me.’ I was sick of waiting. Sick of taking too many shots.” Fresh says he knew it was time to leave when he started dipping into money he put away for retirement. These days, Mannie Fresh wears a pricey-looking watch and a ring, but there’s nothing around his neck. He seems to have left his days of flossing behind him. He also says he’s done rapping after The Mind of Mannie Fresh—the brilliant and playfully un-gangster solo album he put out in December of 2004—didn’t get any kind of push from the label and didn’t sell. As a result, Mannie will be shopping out all of his electro-funk bounce beats featuring triplet hi-hats, dive-bombing snare rolls and enormous keyboard melodies from here on out, and anyone who can pay the price can get down. Fresh isn’t exactly impressed with a lot of MCs he comes across since he made himself a free agent, but he’s found a way to innovate within the limits of what the artist is willing to do. He somehow managed to come out of a Trina session with a bizarre '80s Top Gun monster-ballad sing along called “Da Club,” and if songs as inventive as that can take off, then perhaps other artist will let the mind of Mannie Fresh run wild. “A lot of artists are scared when they see trumpet players show up—they like ‘Nah that ain't what I want,’” he says. “I try to tell them, ‘Dude, I'll give you trademark Mannie Fresh but it's not about keyboards and a drum machine.’ What made Jeezy’s song so good is that we used a live bass player. At first he was like, ‘Nah, can’t you just do it with the keyboard?’ And I was like, ‘No let's do it with a bass player.’” Fresh even says that, if the money's right, he’s down for working with Lil Wayne again. “Everybody knows that me and dude got crazy chemistry. And it just works like that with certain artists. I think that’s the same with Juvenile. He tried it on his own and it was like, ‘No dude—we want to hear you with Mannie Fresh.’”

Over the last decade, Cash Money Records and Master P’s No Limit Records—also of New Orleans—have combined to sell literally tens of millions of albums. Regardless of what anyone thinks about the legacies of the two companies—about the quality of their music, the ethic of their lyrics, the lifestyle that the artists project—the numbers speak for themselves. For the past ten years, New Orleans, the American city with what is inarguably the deepest, richest, most profound musical legacy in the nation, has been utterly dominated by Cash Money Millionaires and No Limit Soldiers in pursuit of more money and bigger everything—diamonds, cars, rims, watches, houses, asses and so on.

Yet when Hurricane Katrina exposed weaknesses in the infrastructure of New Orleans and disaster struck, Wynton Marsalis was everywhere. He organized a tribute concert in New York and played from Duke Ellington’s “New Orleans Suite.” He and Harry Connick Jr. opened another benefit concert with “Bourbon Street Parade.” ABC’s 20/20 followed Marsalis on a tour of his hometown, and promoted the show with a news story that read, “Marsalis’s city is one where blacks, whites, and creoles melted into one big gumbo of a party, stirring in classical, African, and Caribbean beats and inventing the only music that is truly American—jazz.” Somehow, what the story calls “Marsalis’ city” doesn’t jibe with the images of a flooded New Orleans on the television. It doesn’t jibe with that iconic picture of an exhausted young man on the sidewalk outside the Superdome wearing a wife-beater, oversized basketball shorts, and an unlaced pair of Timbs. And it doesn’t jibe with the last decade of New Orleans music.

“Everybody knows that me and [Lil Wayne] got crazy chemistry.”—Mannie Fresh

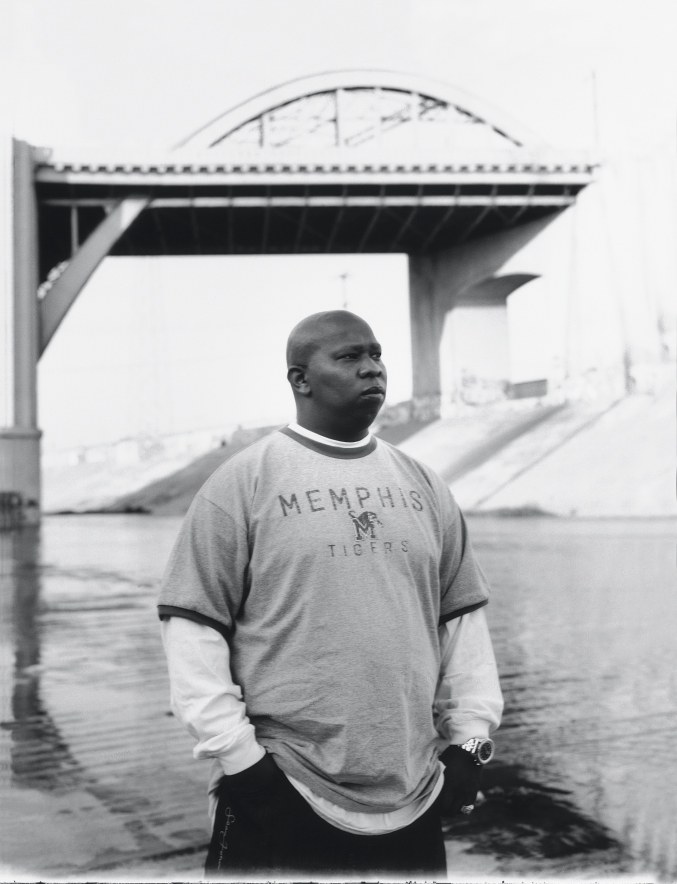

Sitting at a restaurant in Los Angeles the day before he’s set to appear in a Lil Flip video, having been displaced from his home in New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina and his home away from home in Houston by Hurricane Rita, Mannie Fresh remembers a very different New Orleans from ABC’s Great Gumbo Party. He speaks of an almost impossibly segregated city and mentions people who have never set foot outside of the confides of their projects. He talks about the huge mental leap he had to take before he believed it was okay for him to move literally a couple hundred yards out of his hood and into a house in a predominately white stretch of town. He talks about the projects on the Northside of New Orleans that are patrolled by nine and ten year-old kids who smoke weed, inject hard drugs, carry automatic weapons and decide who does and doesn’t enter their hood. It is—or was—he says, as bad as the favelas in City of God. Mannie also tells the story of a recent, harrowing New Orleans tradition: a dude who got himself in trouble might show up at the club to find people wearing T-shirts with a picture of his face of them and the letters RIP. Within a couple hours he’d either be dead or leaving Louisiana for good. As Mannie Fresh puts it, “Nobody from this generation in New Orleans even knows who Wynton Marsalis is, dude.”

When the hurricanes hit, little or nothing was heard from Mannie Fresh. As it turns out, he started by setting his entire family up in Houston. Soon thereafter, Rita materialized, so he led a ten-car caravan East to Memphis. Since then he’s gone back to work, traveling to studios all over the country while simultaneously looking to buy a home in Houston where all of his people will live until they’re back on their feet.

In other words—despite the tragedy—Mannie Fresh is enjoying both the freedom and profits of independence. All the calls that were once going to the Cash Money offices (and no further) are now going direct to the cell phone of Mannie Fresh, and he’s putting in work. Troubled times or not, Mannie’s sense of humor is his most relentless trademark, and like his song intros, there is always a little kernel of seriousness behind his jokes. The outgoing message of his cell phone is currently Mannie himself in a put-on accent, playing a character called Guam. “Greetings, this is Guam,” the message begins. “It’s 2005 and I push a Viper, no longer a Cadillac. But if you are looking for the boss and it is about money, he will get back with you. I am now assisted by an assistant and I don’t have time for this. So peace out, and ohskie whoaskie.” There is, however, never a beep—the mailbox is always full.