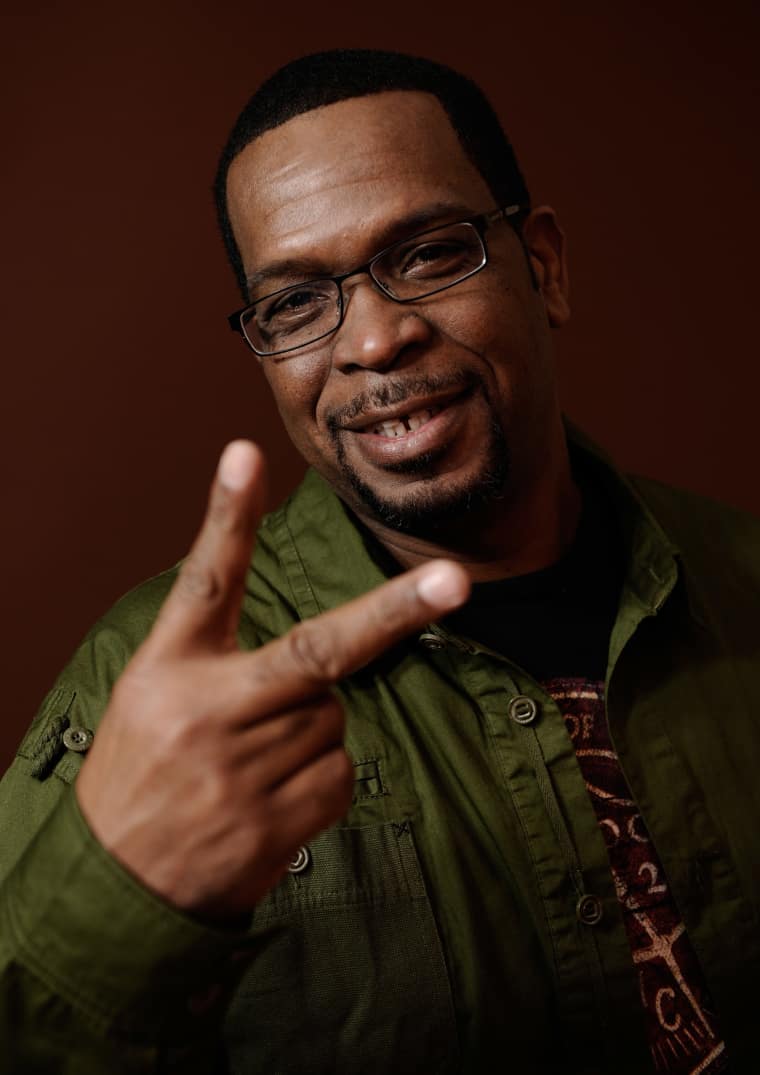

Getty Images / Larry Busacca

Getty Images / Larry Busacca

Getty Images / Larry Busacca

Getty Images / Larry Busacca

While accepting the Source Award for Best New Rap Group in 1995, Outkast crystallized the coastal elitism that dominated hip-hop at the time. The New York audience began lobbing boos at the Atlanta duo, so a daishiki-wearing Andre 3000 grabbed the mic and proclaimed, "The south got something to say." For Luther Campbell, best know as Uncle Luke of Miami's infamous 2 Live Crew, that anti-southern sentiment in hip-hop has been a consistent thread throughout his long and storied career. Though he was an important early pioneer, taking on the Supreme Court and forever changing the way the laws treat obscenity and parody, he's rarely acknowledged for his outsize impact. In The Book of Luke: My Fight for Truth, Justice, and Liberty City, a new memoir that's as informative as it is entertaining, Campbell outlines his life, work, and impact. The FADER recently spoke to him about his legacy and why he doesn't get the credit he deserves.

Perhaps we can start by talking about the story of your Supreme Court case. What do you remember about that time?

Let me tell you. There was so much going on at the time. Here I am, just a young guy that's doing music, minding my own business. Our music was basically comedy. Everybody back then was sampling different types of music like James Brown and all that. And we decided we wanted to sample things like Leroy & Skillet, and comedians like that. To make a long story short, going to the Supreme Court, two things happened that people kinda get confused. We went to the Supreme Court for free speech but the case was a parody case. We lost at the district court. At the federal court, we lost an obscenity trial, where they deemed the record obscene. We eventually got that overturned. The federal judge deemed it obscene, and that's when folks were taking the records off the shelves.

Now, if I did not fight that, then that would've become case law. And that case law could've been applied to any rapper right now. They could've said, "Okay, here's case law. This case law shows that based on what these guys did back then and what these guys are doing right now, it's similar." And then they could've taken any record off the shelf right now if we never won that case. The parody case is so important, that was the one going through the Supreme Court. That was very, very important because the parody was protected by the First Amendment; whether or not we can poke fun and all that, and it all fell in the realm of it being parody. People like Saturday Night Live, any comedians doing parody, if we lost that case, then you wouldn't have seen anybody imitating or mocking other people.

Those were two very big battles that you fought. What do you think it was about you and 2 Live Crew specifically that made them pick you guys as the targets? Because it really could've been anybody at that time.

We were easy targets, and you had a combination of a lot of different things. At that period of time, that's when rap had just started getting into different households. It was an African-American and Latino thing, but now rap had started to cross over into other areas. So when it started crossing over to other areas, that's when it became a problem for the rest of society.

How much of that do you think has to do with race?

Oh, it had a lot to do with race. You had Focus on the Family and all these different organizations coming after hip-hop. The whole thing was, "hip-hop is going to be poisoning the mind." My whole thing was, and the reason that made me fight, is basically I said, "Hey listen, here's a situation. I'm seeing this thing twenty years from now." I'm seeing that, if white kids like hip hop, then white kids'll get a good understanding of how black kids are living, and then there won't be this separation. It'll actually bring races together, much more than anything. So when I walk right now into a white club on South Beach, and I hear these kids playing the music, when I hear that—everybody listening to the same music, everybody wearing the same clothes—I know it's a whole different appreciation. When I look at everything, that's what I fought for. For everybody to be the same.

Was that something that you were aware of while it was happening, or was it something you figured out a little bit later?

No, I figured that was going to be the situation. Because here I am, I'm the record executive. I own the record company, so I'm looking at where the record sales are at. We started selling these records in white communities, white households. We're doing concerts for white fraternities and everything. When I looked at that, I was like, "Okay, this is what we got right here. This is why the pushback is coming."

Something like 20-25 years later, you're still known for being Uncle Luke, but you wind up running for mayor. Tell me a little bit about the circumstances surrounding that.

Obama energized a whole race of people. All these young people through Facebook, through the internet, it got them all energized and excited about voting. So I realized all these young people had these voter's registration cards but on the local level, nobody excited them. So, hey, now that we've gotten them to get the card, let's see if we can get them to use it. At the end of the day when I ended up getting 20% of the vote, I had a good idea that that was gonna happen. I'm having meetings with anybody and everybody that's running for office in Dade County.

Ten or twenty years ago, it wouldn't have even been conceivable for someone who was involved in rap to end up in the position that you're in now. What do you think has changed to make it acceptable?

I think it's the fights. All the fights. Every fight that I've had to take on that made rap acceptable right now. People don't understand the significance of that. When I see people not writing about it or when I see people not talking about it, or when they try to erase me from the history books, that upsets me. Because that's a very rare and important part of our hip hop history. It ain't just Russell Simmons, Andre Harrell, or Jay Z, or Puff Daddy. The history behind this—it ain't just Kool Herc. Herc started hip-hop, but at the end of the day, who fought for hip-hop? I just want my just due. That's one of the reasons why I wrote this book, so people can know the history.

In the book you talk about the fact that being from the South made you excluded from mainstream hip hop, in a way.

Yeah, that was the whole thing, because we were a group that people didn't want. They didn't want hip-hop in the South. The artists of the North didn't want us involved in the music business at all.

In the context of the Tipper Gore, anti- rap movement, when we talk about that in pop culture, people usually bring up N.W.A. People don't bring up 2 Live Crew.

No, they never do. And we were number one on the list. But again, that's a group from California versus a group from Miami. I'm a rebel. I heard a quote somebody made the other day, and it kinda stuck with me. It was along the lines of, "The person who sets the standards, and the person who fights, they always get left behind because they were the rebels. They were the individuals that fought from the beginning." And I'm okay with that.

Getty Images / Joe Raedle

Getty Images / Joe Raedle

What's the ideal situation for you, going forward?

I'm happy right now. I'm happy that this book is out. The Grammys, MTV, BET, they ain't gotta do nothing for me right now, because I'm good. I've said what I have to say in this book. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, all of them. I'm good. Man, I don't need nothing. I feel vindicated. I don't feel like Rodney Dangerfield in the music business anymore.

What is ultimately the one thing that you want people to know that they might not already know?

They look at me like 2 Live Crew, the rapper. The most important thing they don’t know is that I'm a very good executive. They don't know that I started a record company out of my mother's house. I created an empire of 100 million dollar companies, and successful artists like Pitbull, Trick Daddy, H-Town, and 2 Live Crew. It's me. The guy with no education, and I'm an executive. I put myself on the level of Jimmy Iovine and all them guys, but again, I'm the guy from the South, so I wasn't gonna be given that same opportunity.

Do you think that's changing at all, with cities like Atlanta getting more recognition for their cultural output?

The day you see a major record company open up in Atlanta, that's when it would be getting the recognition. But as long as they got satellite offices, no. When you see a major corporation open up in one of those areas, one of those Fortune 500 companies, just like Lockheed Martin, when they make decisions about music like that, that's when the South has arrived.