Skepta’s Mission

Cover Story: Skepta’s leading grime into the future by returning to its roots.

It’s a mild spring evening, and about a thousand young Londoners have gathered on the uneven gravel and dirt of the Holywell Lane Car Park in Shoreditch, beer cans and spliffs in hand, going completely berserk to grime. This show has no tickets, no VIP, and no permit, just a borrowed sound system set up on the back of a truck parked under a railway overpass. The gates at the entrance have been swung shut, so scores of hyped-up fans are climbing over the 10-foot high wire fence to get in.

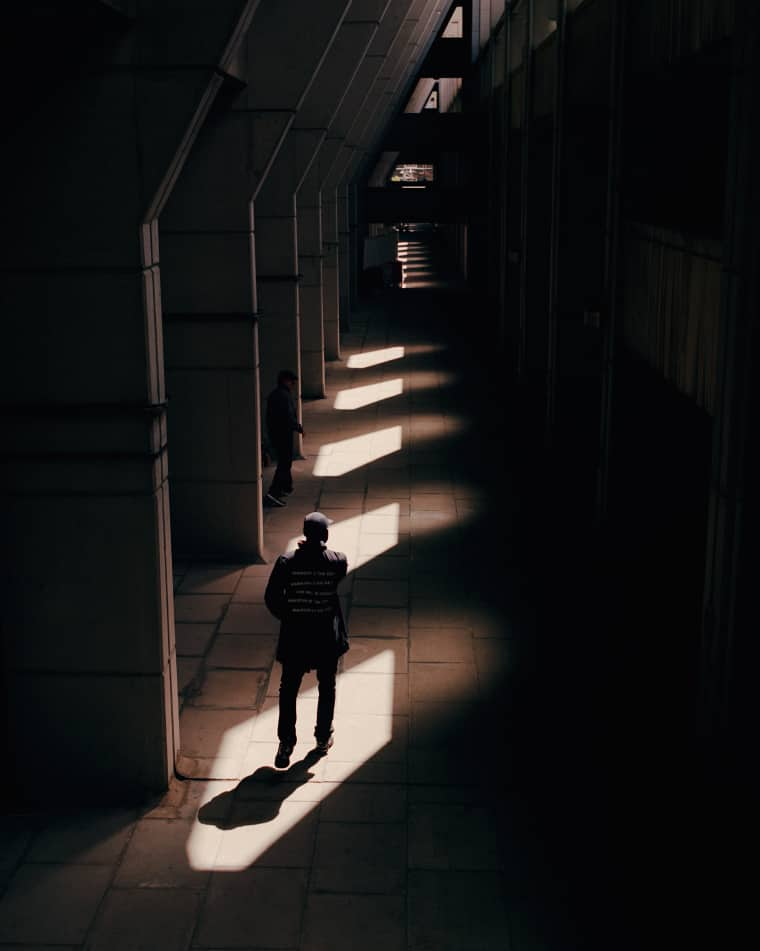

The man who brought them here is the 32-year-old MC and producer Skepta. He’s wearing a long black jacket with the words “anarchy is the key” written in rows across the back, bounding back and forth across the makeshift stage, trying to get everyone present to raise their middle fingers to the sky and shout, Fuck the police! “It’s a British thing, it’s a London thing, it’s a shutdown thing,” he bellows. “And we’re going on until they shut us down.”

He’s revving up the audience for his just-released single, “Shutdown,” a three-minute ode to his own rising profile. Want to know how I did it with no label, no A-list songs?/ I told them, blud, I just shutdown, he spits over a classic grime beat, with a grinding bassline, brash keyboard riff, and sparsely placed artillery-fire drums. The crowd erupts, and as in Jamaican dancehall, so in grime: if the crowd goes crazy enough, you rewind the record and go again. After 40 minutes, the police do show up, but before any names are taken or arrests are made, Skepta and his friends have already slipped offstage and disappeared into the mass of bodies and weed smoke, their mission complete.

The event feels like a poignant moment for grime, England’s aggressively fast-paced, proprietary blend of UK club music, dancehall, and American hip-hop. Since exploding out of the city’s underground clubs and pirate radio stations in 2003, the sound has been smothered by gentrification and racist policing, making its recent resurgence—and this gig—even sweeter. The car park is only a five-minute walk from Cargo, the venue where Skepta launched his 2007 debut album, Greatest Hits, to a sold-out crowd; within three years, Cargo had banned its DJs and promoters from booking grime acts or even playing grime records. It is also a five-minute walk from Plastic People, the tiny basement dive once home to Rinse FM’s FWD>> party, the long-running club night that helped incubate dubstep and grime, often with Skepta on the mic. After several years of harassment from the police and local authorities, Plastic People shuttered last year; to many music fans, its closing represented the high-water mark in a tide of gentrification that has turned Shoreditch into corporate hipster ground zero, full of pop-up stores and overpriced street food.

Like grime itself, Skepta’s star has waxed and waned since his beats first exploded onto London’s airwaves. He made instrumentals initially, before grime godfather Wiley persuaded him to pick up the mic. Over his 13-year career, he’s had five Top 40 singles in the UK, and hardcore underground anthems, beefs, albums, mixtapes, and controversies in abundance. But his 2014 single, “That’s Not Me”—with its taut, no-frills production and low-budget video—marked a dramatic sharpening of focus. Following a few years of new sounds and looks, “That’s Not Me” felt like both a disavowal of past mistakes and a return to his roots, with Skepta triumphantly distancing himself from the glamorous trappings of the jet-setter life: Sex any girl? That’s not me/ Lips any girl? That’s not me/ Yeah, I used to wear Gucci/ Put it all in the bin cause that’s not me.

The track won him new friends in the US. In September, it led to a riotous collaborative remix with Ratking’s Wiki, and then, this past February, to an all-important co-sign from Kanye West. A few hours prior to the UK music industry’s annual BRIT Awards, West reached out to Skepta and asked him if he could round up about 30 friends for the premiere of his new single, “All Day.” The performance—which included a human wall of his London “mandem,” all dressed in black, and a couple blowtorches—caused a sensation before the starched shirts of the UK industry. It also turned a few crucial heads overseas: the week after our interview, Skepta is set to fly to Los Angeles to log studio time with both Earl Sweatshirt and Drake. (In the end, the sessions with Drake are pushed back due to scheduling issues.)

The day after shutting down the parking lot in Shoreditch, Skepta is back in the neighborhood to visit the Young Turks studio, still wearing his “anarchy is the key” jacket. The hangovers have set in deeply from the night before, and in contrast to his bullish persona onstage, he’s quiet today, huddled inside his black hoodie. His friends curl up on the sofa, shades down, while Skepta gets up and, despite his hammering head, starts tinkering a few improvised melodies on a piano. One of his phones went missing somewhere in north London last night. “Don’t worry,” he says. “I need a new one anyway.”

He is here for a catch-up with London vocalist Acyde, one half of the band We Are Shining. When talk turns to Skepta’s upcoming album, Konnichiwa, Acyde asks whether the imminent sessions with Earl Sweatshirt and Drake are going to change the direction of the record. “Bruv, I put P. Diddy on a fucking grime tune,” Skepta says, perking up a bit as he refers to the time the American rapper recruited him to produce the beat and write a verse for the official “Grime Remix” of his 2010 single, “Hello Good Morning.” “I don’t care what they feel about it. They have to come on my wave—that’s the only thing that’s going to give my album what it needs. I understand the objective now, and I ain’t going to fucking America to shoot a video. They need to come to the roads with me.”

"I understand the objective now, and I ain’t going to fucking America to shoot a video. They need to come to the roads with me.”—Skepta

The roads were precisely where New York rapper A$AP Bari appeared last October, after he flew to London to appear in the music video for their transatlantic collaboration, “It Ain’t Safe.” The hand-held clip sees the A$AP Mob member bopping around on an ill-lit street corner in Tottenham, wearing a tracksuit. The message seemed loud and clear: if American hip-hop was ready for its grime moment, with Skepta at the helm, they were going to have to do it on grime’s own terms.

That reverence for the genre’s history is palpable on the 11 tracks Skepta has recorded for his album thus far. One of them opens by sampling a legendary 2001 onstage lyrical clash between Pay As U Go and Heartless, two of the biggest crews in grime’s parent genre UK garage, the skippy 2-step or 4x4 club music movement. As the clash proceeds, things start getting more and more heated, and amidst audibly mounting anger, a then-young Wiley grabs the mic and implores, “Lyrics for lyrics! Calm!”—four words intended to remind his fellow MCs that musical beefs ought to remain that way.

The clash occurred at a pivotal point in Britain’s music history, when UK garage was splintering between syrupy chart hits, typically with female singers on the chorus, and a darker and more ominous variant of the sound, accompanied by (mostly) young male MCs, like those present at the infamous Pay As U Go and Heartless clash. Over the following two years, this darker garage would morph into grime. Incubated on pirate radio—a network of illegal and hyper-local FM stations that were vital to grime, just as they were to dubstep, UK garage, and jungle before them—the new sound was disseminated by a new generation of teenage MCs and producers making sparse but devastating beats, often using cheap home PC software or video game consoles. By 2003, Wiley’s protégé, Dizzee Rascal had exploded onto the popular consciousness, winning the Mercury Prize for his debut album, Boy in Da Corner, and introducing the world beyond London’s council estates to the sound.

Skepta was born Joseph Junior Adenuga, to immigrant parents from Nigeria. The eldest of four siblings—including his partner-in-grime Jamie, who MCs and produces as JME—he grew up on Meridian Walk estate, a housing project in Tottenham, in north London. Beneath the adult Skepta’s thoughtful seriousness, you can sometimes detect a certain shyness, and it’s one that dates back to his formative years. “In school, I wasn’t like the cool guy who had all the new clothes and had all the girls,” Skepta remembers. “I felt like the world saw me as an idiot.” Some of that stemmed from being a second-generation African immigrant, with a surname that challenged some of his teachers. “In school, when a teacher would try and read my name, as soon as she goes to try and say it, I’d be trying to say it first, to stop the embarrassment of her not being able to pronounce it,” Skepta says. “I remember one day when I was about 15, my mum told me, ‘Junior, your name means something—just because your name isn’t some standard English name.’ I remember going back into school, and it started to power me up. Bare self-hate vibes was pushed into me as a kid at school, trust me.”

Musically, growing up in Tottenham meant “reggae in abundance” for Skepta: Barrington Levy, Gregory Isaacs, and Half Pint were on permanent rotation at home, until his dad bought him Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle on cassette when he was 12 and he had his mind blown by hip-hop. At school in the early 1990s, he got into the frenetic London sound of ragga jungle, a fusion of futuristic rave music and Jamaican dancehall. “When I first heard jungle, I understood it immediately,” he says. “To make something this bless sound this hype was just sick.” In his later teens, Skepta began hanging around pirate stations, eventually landing his own show DJing on Heat 96.6 FM.

Helming the radio show, Skepta was unapologetically pragmatic when it came to getting hold of the best tracks to play. “If I heard a DJ play a song on the radio and I liked it, I’d record it,” he says. “I’d copy from radio to tape to minidisc, then from minidisc to [vinyl] dubplate, and then play it on my show.” Eventually, he began incorporating his own instrumentals into the show’s mix of early grime, UK garage, and American rap. He’d started making beats in his bedroom using “any program I could get my hands on,” including Mario Paint on the SNES and Music 2000 for PlayStation. Perhaps owing to grime’s Jamaican heritage, in the first few years of its lifespan, the genre consisted primarily of instrumental riddims. “What people forget, before the MCs vocalled them, instrumentals had names,” says Skepta. “We’re talking about a name that the whole country call it by. [Wiley’s classic riddim] ‘Eskimo’ was called ‘Eskimo’ before an MC spat on it. And the tracks become so big that even if an MC spits on it, or adds a chorus or whatever, people are still going to call it ‘Eskimo.’”

One of Skepta’s first releases—2002’s “Pulse Eskimo,” an utterly ferocious instrumental he built on Music 2000—is accompanied by an appropriately grimey origin story. “I gave it to a few DJs in the hope they’d start playing it,” Skepta recalls, “and one of them—I don’t know if it was Mach 10 from NASTY Crew or Karnage from Roll Deep—they played it at [classic grime night] Sidewinder. And when they played it, someone started letting off gunshots in the dance.” Chaos ensued, and though no one was injured, the tune has been known as the “Gunshot Riddim” ever since. Eventually, Wiley put it out on his own Wiley Kat Records, as a 12-inch white label with no sleeve and the track written on in marker pen.

Skepta came relatively late to MCing, penning his first bars at age 21, the night after a studio session with Wiley where the elder MC suggested he try his hand at writing lyrics. He quickly developed a reputation for devastating “war dubs” aimed at rival MCs, weaving together tales of north London street life with positive assertions of his Nigerian identity. “When I was a youth, to be called ‘African’ was a diss,” Skepta remembers. “At school, the African kids used to lie and say they were Jamaican. So when I first came in the game and I’m saying lyrics like, I make Nigerians proud of their tribal scars/ My bars make you push up your chest like bras, that was a big deal for me. All my early lyrics were about confidence. I can hear myself fighting back.”

Grime’s early years were frenetic, and the blurring of the lines between having a “music crew” and a “street crew” became a problem for Skepta, especially as his career started taking off. The same year he started MCing, he and JME’s neighborhood crew, Meridian, was implicated in a shooting; their fellow Meridian MC, Bossman Birdie, received a three-year jail sentence for his part in the crime. The Adenuga family was evicted from the estate, and relocated two miles down the road, to Palmers Green. With Bossman in jail, and other members of Meridian distracted, JME and Skepta started falling in with Wiley’s renowned east London crew, Roll Deep. But when Roll Deep’s debut album, In at The Deep End, came out later that year, and the brothers weren’t on it (having joined too late), they realized they needed to start their own unit. JME founded Boy Better Know, an independent label and clothing line, and has never looked back, releasing all of Skepta’s albums and mixtapes and six of his own, even though the brothers still count Wiley as a mentor and friend.

“England is so plain, like a burger with nothing on it. That’s why it’s so real.” —Skepta

The entirely homemade creation of Boy Better Know was an extension of grime artists’ remarkable ability to hustle: the conventional music industry was foreign to them, but they had their own infrastructure, and the genre was thriving. “It was so DIY back then,” recalls Skepta. Each time he played Heat FM, he would pay £20 toward the running of the station. Even in the short term, it was an investment worth making: he says he sold “literally thousands” of his white label vinyl instrumentals in London’s record shops, typically driven straight from the pressing plant in the back of a friend’s car. “It was a priceless hustle, man,” he says of his success marketing and selling his own music without the support of a major label or management team. “Pirates were like the sickest, most rebellious type of pop-up that you could ever have.”

Skepta’s 2007 debut album, Greatest Hits, arrived just as the UK music industry was beginning to lose interest in black British music. There had been a major-label goldrush following Dizzee Rascal’s success, with a handful of album deals for the likes of Shystie, Lethal Bizzle, Kano, and Roll Deep, but these album projects were often commercial disappointments or didn’t come out at all, and the industry quickly moved on. Meanwhile, the internet was rendering grime’s grassroots infrastructure—its pirate stations, raves, record shops, and vinyl dubplate culture—increasingly obsolete.

By the end of the decade, a handful of underground MCs finally started having major chart hits—but it wasn’t with grime. Beginning with Wiley’s “Wearing My Rolex,” a clear pop formula emerged, seeming to promise MCs a chance at becoming household names alongside their American peers. A succession of electro-pop bangers primed for poolside parties in Ibiza followed, typically involving simpler or slower rapping, lyrics about cars and girls and holidays, and sung or Auto-Tuned choruses. Skepta joined the party for a moment, releasing a succession of dance singles between 2008 and 2012, about which he has no regrets. “In my head, Dizzee and Wiley were the people that I was looking up to,” he says. “That was all I knew! If my man makes a dance tune, I’m making a dance tune. But then I came to this point in my life recently where I was like ‘Rah, I’m a man—like, maybe I’m a leader? Maybe I should make a new path?’ And that was when I just stopped looking to Wiley and Dizzee as the blueprint. You’ve got to fucking take that baton and run with it, to make your own blueprint.”

To hear him speak of it, Skepta’s recent resurgence was the direct result of an epiphany about who he is, and who he isn’t. “I’m on Tottenham High Road, bro, and I’ve never seen anybody topless with all their chains on, outside a brand new convertible, popping champagne,” he says. “And as soon as I realized that, everything started going well.” It’s the same philosophy he outlines on “That’s Not Me,” one about rejecting all pretension and compromise and returning to the source: the sound of London’s streets. That renewed sense of purpose seems to have come at the right time, as the off-kilter beats and lyrical velocity always present in grime began to coincide with a growing sonic openmindedness in American hip-hop. When Drake is posting YouTube screenshots of Skepta’s infamous 2006 clash with Devilman on his Instagram, it’s hard not to notice the way the wind is blowing.

Palmers Green is eight miles north of the Shoreditch rave and two miles north of Skepta’s childhood home, and although it’s not nearly as genteel as its name suggests, it has a suburban feel, by London standards: tree-lined residential streets, long but unimpressive front lawns, and chip shops that haven’t changed their décor since the 1970s. “England is so black and white, so plain, like a burger with nothing on it,” Skepta will say at one point, trying to capture his home’s almost defiant lack of Hollywood glamor. “No salad, nothing. That’s why

it’s so real.”

Of course, staying in touch with your roots is a lot easier when you’re still based in your parents’ old house. (Skepta’s parents recently moved back to Nigeria, leaving the place to him.) He opens the door in a black tracksuit and a black Nasir Mazhar hat, midway through an anecdote he’s telling everybody present about Jean-Claude Van Damme doing Coors Light adverts. When Skepta has something to say, he’ll happily hold court. He and a friend just watched all of the ads on YouTube, cracking up laughing, but there was a lesson in it, too: something about the sad decline of a Hollywood icon, about the importance of playing the long game.

Once everyone has arrived in Palmers Green, we set off in Skepta’s silver Mercedes and cruise around Tottenham, winding around the A406 North Circular orbital road to pick up some lunch from a place called Caribbean Junction. “I’ve been going here forever, man,” says Skepta. “It’s a real Tottenham landmark.” He is certainly treated like a prodigal son when he walks in. As the saltfish patties and rice and peas are prepared, the owner asks him and his crew to line up underneath the menu board for a photo. Skepta regales everyone with a childhood story of seeing his mum biting into a raw Scotch bonnet chili pepper and deciding he wanted to emulate her. “I was crying for about two hours, man,” he says, shaking his head. “She had to take me to hospital.”

Having collected the food, we jump back in the car and drive south down Tottenham High Road, en route to a friend’s studio. It was on this precise strip that the English riots began in August 2011, starting with peaceful protests outside Tottenham Police Station. Locals demanded answers about the police killing of 29-year-old Mark Duggan in broad daylight, just around the corner, and failed to get them. Back then, I saw molotov cocktails hurled at the police lines and a red London double decker bus burned to a cinder; over the next five days, around 30,000 people across England took part in riots, arson, and looting. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Mark Duggan was a friend of Skepta’s—he’s even in the background of his 2009 video for “Look Out,” with Giggs. Driving with Skepta past the epicenter of the riots, I’m reminded that even if grime’s most obvious outward characteristic is a thrilling, in-the-moment velocity, there is an implicit sense of political righteousness somewhere there, deep in the bloodstream. As Skepta told The FADER in a video interview earlier this year, discussing the connection between American rap and UK grime, “We all make different types of music, but it’s all born from poverty—it’s all born from pain.”

"I believe in my talent so much, it’s crazy. It’s not about a record label to me.”—Skepta

To judge from the way Konnichiwa’s tracks are sounding so far, Skepta seems determined to capture this London, rather than playing into someone else’s fantasy of it, or of Ibiza, or of New York, or anywhere else. But it also sees him digging further into his African roots—on one track, he calls himself a real Nigerian hotboy, brought up on rice and stew. On another—“Chop,” a collaboration with vocalist Martel B—he takes inspiration from a freestyle Nigerian MC Davido once performed on the legendary UK hip-hop DJ Tim Westwood’s show. Nigerian and Ghanaian Afrobeats—an umbrella genre that blends R&B, dancehall, pop, and rap, inflected with local instruments and languages—has surged in popularity among young black Londoners in recent years, and this shift toward diasporic African pride has cheered Skepta. “It makes me happy to see all these kids today just love Afrobeats, because since the start I’ve been trying to fucking fight for this ting, for them to be able to stand up,” he says.

On “Chop,” even Skepta’s vocal delivery has a Nigerian twang to it—but it also has the dark-side atmosphere and pared-down production unique to grime. With the exception of one beat, Konnichiwa was produced entirely by Skepta himself, mostly from an old-school toolkit: hard kick-drums and bass; raw lyrical energy; the odd twinkling piano riff or brass volley. “I want anybody from around the world to be able to listen to the album and know it comes from London,” he says—“from the beats, not just the vocals.”

Konnichiwa had initially been scheduled to come out in March 2015, but all his success this past year, in addition to a new management team, have forced a new strategy: he wants to take his time and get it right. His management is having meetings with labels, but only for a partnership on the marketing and distribution side. The grassroots mentality has become a habit he can’t—and doesn’t want to—shake. “Somewhere in my heart I feel like I’m way past a record deal now,” he says, as we sit in his car at the end of our drive together, back outside his parents’ old house. “It’s pointless to me. I believe in my talent so much, it’s crazy. It’s not about a record label to me.”

There’s a certain amount of poetic justice to Skepta’s story, not least in the fact that after 13 years of ups and downs, he’s still just as independent-minded as he was when he started out. It’s a journey that mirrors his parents’ recent return to Nigeria, and the spirit of patience and perseverance for which they are understandably proud of him. “I see my mum sometimes in a Boy Better Know T-shirt,” he says, smiling. “It makes me happy, man, because I know that they’ve seen so much. You’ve got to imagine: my mum and dad have been in Nigerian wars and shit. So you move to England to make a better life for your children.” Skepta may be on the verge of global recognition, but his greatest goal as a musician hits a good deal closer to home. “I want to give them that house in Nigeria,” he says. “Finished, done, built. For them to look back on this and say, ‘You know what? That’s what we went to England for.’"

Spend a day in New York with Skepta: