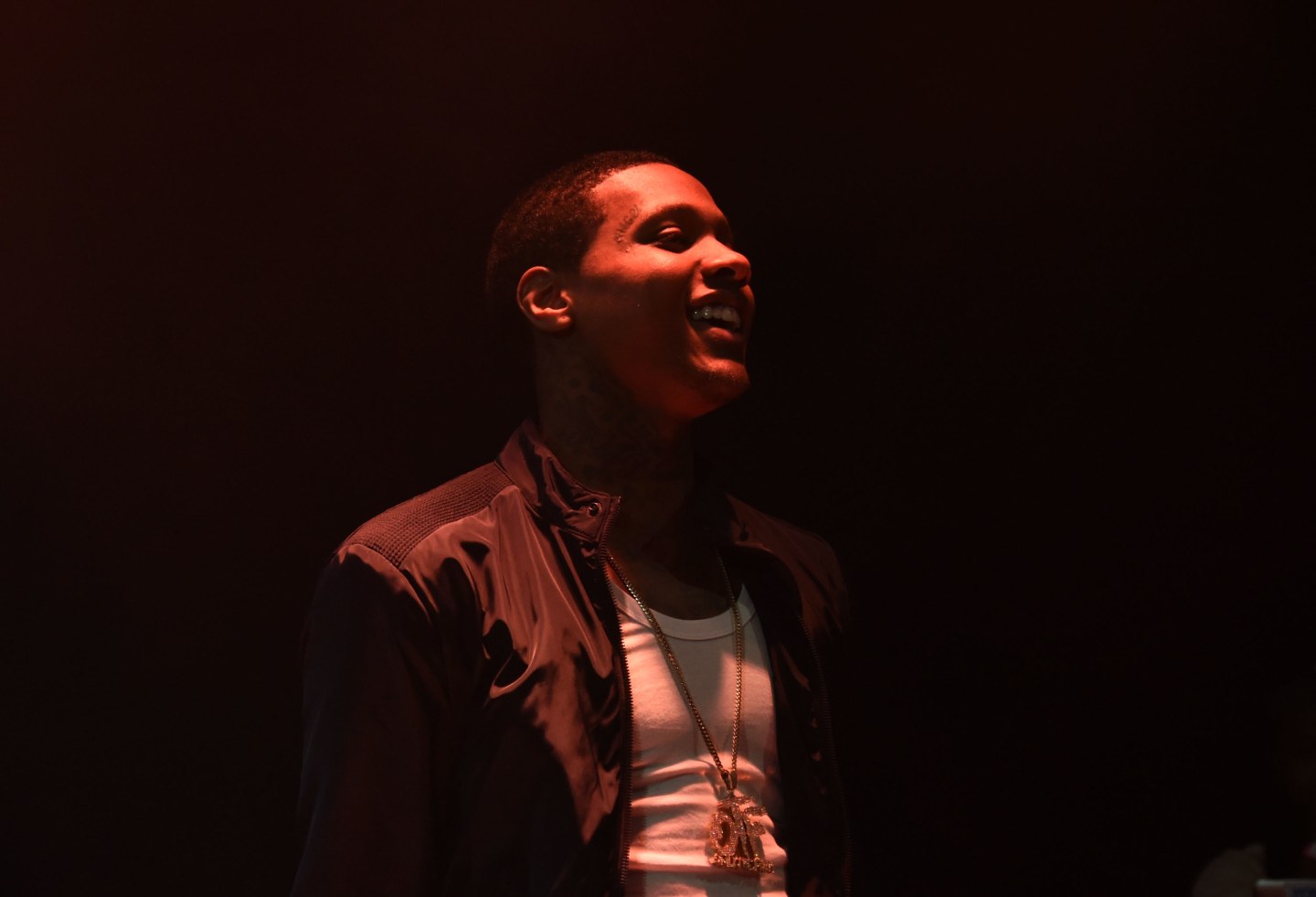

Ilya S. Savenok/Getty

Ilya S. Savenok/Getty

Three years ago, Lil Durk signed to Def Jam, in a wave of major label signings of Chicago artists. The city’s young rap scene had exploded after a music video Chief Keef filmed at his grandmother’s house caught the attention of Kanye West and teens everywhere, and affiliated acts, like Durk, benefited from the shine.

“We’re all from the same area, so [business] can’t really break us up,” Durk told The FADER in 2012. Three years later, he says Chicago’s scene “ain’t really moving the way it was.” Last fall Keef was dropped unceremoniously from his label; for years, Durk’s album release was delayed. “It was nobody else’s fault but mine,” Durk says now of the setback. “The music wasn’t finished because I was forcing songs just to have it done. I didn’t want to do it that way.”

Today, Durk released his debut album, Remember My Name, via Def Jam. In May, he sat down with The FADER in New York, and opened up about what he sacrificed to record it, what Chicago was like in 2012, and how it feels to step out of the city’s shadow.

Lil Durk: Three years ago, I never thought I’d be where I am today. Once upon a time, I was really lost. I was 18 going on 19, and I was shy. All I want to do is get money, and the way I was thinking I was going to do that was a negative route. Like, I was just going to try to rob somebody, you know what I’m saying?

I never even thought I’d be rapping. I just tried it out of the blue ‘cause I used to work with a guy named DGainz, who was famous in Chicago—he used to shoot videos for all of the artists in Chicago. He came over to my house and he had his camera so I was like, “Let’s rap.” We shot a video, it was a thirty second clip, and when we dropped it, it got like 5,000 views in two days. That was a lot for back then, so we were like, “We gotta rap.” Fans started calling me Durk, or the name of the song, “I’m A Hitta.” We started taking it seriously from there.

I went to jail when I was 17. That’s when I really slowed down; I really had time to think. My first son was born when I was in there and I had no money. So I was like, what am I going to do? I wasn’t think like, “How am I gonna get rich?” But when I started seeing the buzz, I was like, “Yea, I love this, I could do this.”

At the time, out of the whole Chicago scene, I was the underdog. Being around [GBE], I was like, I need your co-sign. But half of the time it didn’t really go like that. Half the time it was a real hassle and a real struggle to get on songs with them. Everyone was just in their glows.

The music changed everyone. At first it was all family, all happy happy. And then the music came along and we started getting big headed. At that time, I was hoping it wouldn’t have happened like that. But that’s how it happened.

So I branched myself off and I just took time to myself, instead of getting in all the other people’s faces or trying to get them help me. I sat down with my team and came up with a plan to separate from the Chicago movement, to make my own movement. You ain’t really want to get involved politics-wise back in Chicago, so I was trying to take a different route.

I’m still on the rise, but it feels good to hear people say, like, “Durk and the other guys”—to show people that I could be the the one with buzz. They were saying Keef was hot—and it’s all love between us now—but I couldn’t be nobody’s shadow.

Look at the Chicago scene now, it ain’t really moving the way it was. If I had stayed right there under the shadow, I’d be stuck. But coming from feeling like the underdog to standing on top of the city, it feels good. It feels good just to keep working and to be motivated by the hate going on but to still be able to do Stop the Violence programs and to be a part of Chicago period.

But I had to sacrifice to get here. I had to sacrifice friends, I had to sacrifice my house because I used to live in the wrong area. I had to stay out of the streets, stay out the way. I had to sacrifice the streets.

My family stuck with me through it all, though. I have three kids, and that’s a big part of staying focused. You don’t want to go outside and see somebody else’s kids got the new stuff and your kids ain’t really got the newest stuff. When I had my first son, I had no money, and it hit me in the head when I looked outside. I want my kids to be able to live comfortable and go to school and to be into sports. I’m going to support my kids to do whatever they want to do, but I’m going to make sure it’s the right path. I don’t want them going through this lane that we going through right now, like the BS in Chicago. I don’t want my son to be another shadow, he’s got to do something different.

These days, I have more to talk about when I rap. Everything I’ve seen in these last few years—I’ve been going out of town, I’ve been to L.A., to Puerto Rico—has opened my mind. And I recorded this album in Atlanta and L.A., where the vibes are just crazy. I worked with Ty Dolla $ign, YG, Nipsey Hussle, Metro Boomin—I build relationships, and I try to stay afloat with everyone who is hot or cool, period. I got fans Migos ain’t got; Migos got fans I ain’t got it; so I’m going to do a song with you so we can connect, and now I got more fans buying more albums and mixtapes.

When I was first starting, I would just get a feature and drop it. All I was feeling was anxiousness. I was young and we had no money, so everything was moving too fast. Now, when I get a feature I know I need artwork, I need to talk to the DJs. It’s called roll out. Everything I do, it gotta have roll out to it. If I take a picture, it gotta have roll out; if I want to put anything on the internet, it gotta have roll out. Because if it doesn’t have roll out, what’s your plan next? Why you thinking after you move?

I learned a lot from other artists, like Meek Mill and French Montana. All three of us were in the same position—all three of us went to jail—and they were sharing advice with me because I’m still young, so I won’t to mess up my future. I really want everything to be more positive than negative.

I never thought I’d be a priority. I used to always think, I should just drop mixtapes and try to get out there. There wasn’t a long-term vision. I never thought I’d walk in the Def Jam building and be a main priority, like I am right now. It feels good. All the work I’ve put in has been paying off. I’m getting booked for shows, being able to drop an album, being able to feed my family. I feel successful now.