Cover Story: Kacey Musgraves

She’s a millennial remaking country music to be more accepting. Turns out that’s how the best country music always was.

The old joke used to go: “What do you get when you play a country song backwards? You get your wife back, your house back, your truck back, your dog back…” These days the clichés are worse: you’d get your booze undrunk on a tailgate unpartied, an unshaken ass in jeans that aren’t cut off. Scanning the FM dial, it’s as if the same hacks who ushered in the demise of rock radio—by pandering to mall rats with pop-punk and egregiously pushing boundaries with rap-rock—have found a new genre to pillage. Bro-country. Hick-hop. With increasing abandon, country music has gone astray.

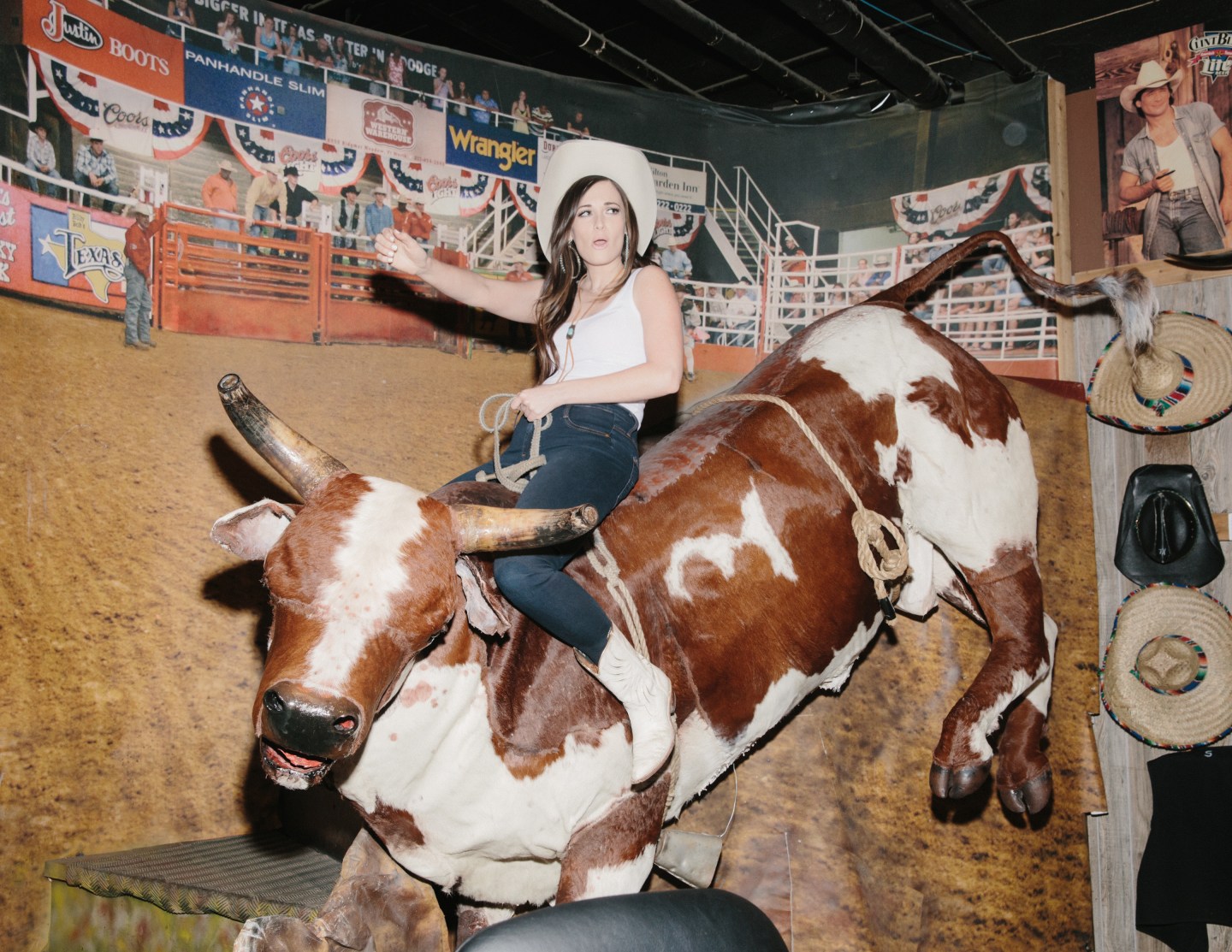

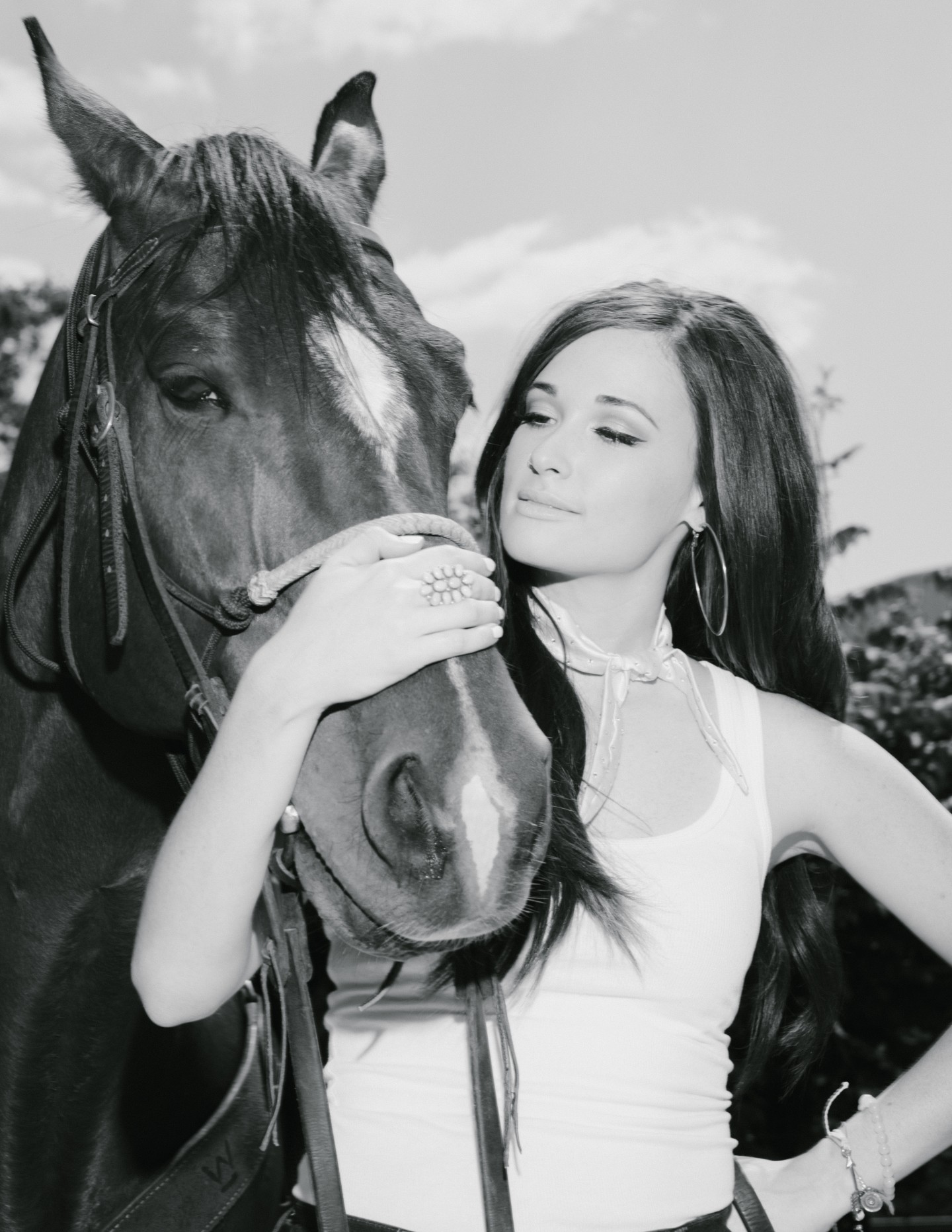

There are, thankfully, exceptions. The rise of Kacey Musgraves, these past two years, with her family-band sound, rural Texas upbringing, and credentials as a working songwriter, feels like a back-to-basics corrective to a genre that’s somehow forgotten how much it used to love basics. Musgraves’ first single, “Merry Go ‘Round,” was a feat of banjo-led tradition that also declared itself modern in its first three lines: If you ain’t got two kids by 21/ You’re probably gonna die alone/ Least that’s what tradition told you. Critics from NPR and the New York Times celebrated her progressive words and conservative sound. Kiss lots of boys, or kiss lots of girls if that’s what you’re into, she sang on her second breakthrough track, “Follow Your Arrow.” Light up a joint, or don’t. When I meet her for the first time on a bright white Texas morning, just about the first thing 26-year-old Musgraves does is swap nose rings with her sister, so she’ll look better for the photos we’re about to shoot on horseback. She’s not your usual country star, nor is she anything but.

They don’t always play her on the radio—“Merry Go ’Round,” her highest-charting song, peaked at just #10 on Billboard’s country airplay chart—but sales and praise have been enduring. “Merry” went platinum and took home the 2014 Grammy for Best Country Song. Her major-label debut, Same Trailer, Different Park, is certified gold and won Best Country Album at both the Grammys and the American Country Music Awards. This summer, she’ll release its follow-up, Pageant Material. Partially written around the same time as Same Trailer, it sticks closely to the themes and sounds that comprise Musgraves’ already-trademark brand of kitschy, catchy country tunes. The album title, in part, is a reference to criticism over a bored-looking frown she was caught making on camera while losing Female Vocalist of the Year at the 2013 CMA Awards to country’s current-day queen, Miranda Lambert. A fellow Texan five years Musgraves’ senior, Lambert grew up just 20 miles south of her, shared a childhood guitar teacher, and released “Mama’s Broken Heart,” a song Musgraves originally co-wrote for herself that has so far sold better than anything Musgraves has actually put out.

Pageant Material is ironic: it’s what Musgraves feels she’s not. “Especially for women, you need a certain face at award shows when you lose or you’re an asshole,” she says. “You can’t have a potty mouth or an opinion. In the South, getting judged on superficial stuff is a real thing. And I’m not attacking the people that might get something positive out of pageantry; I’m just not into being judged in that way.” Paraphrasing the album’s title track, she adds, “I’d rather lose for what I am than win for something that I’m not.”

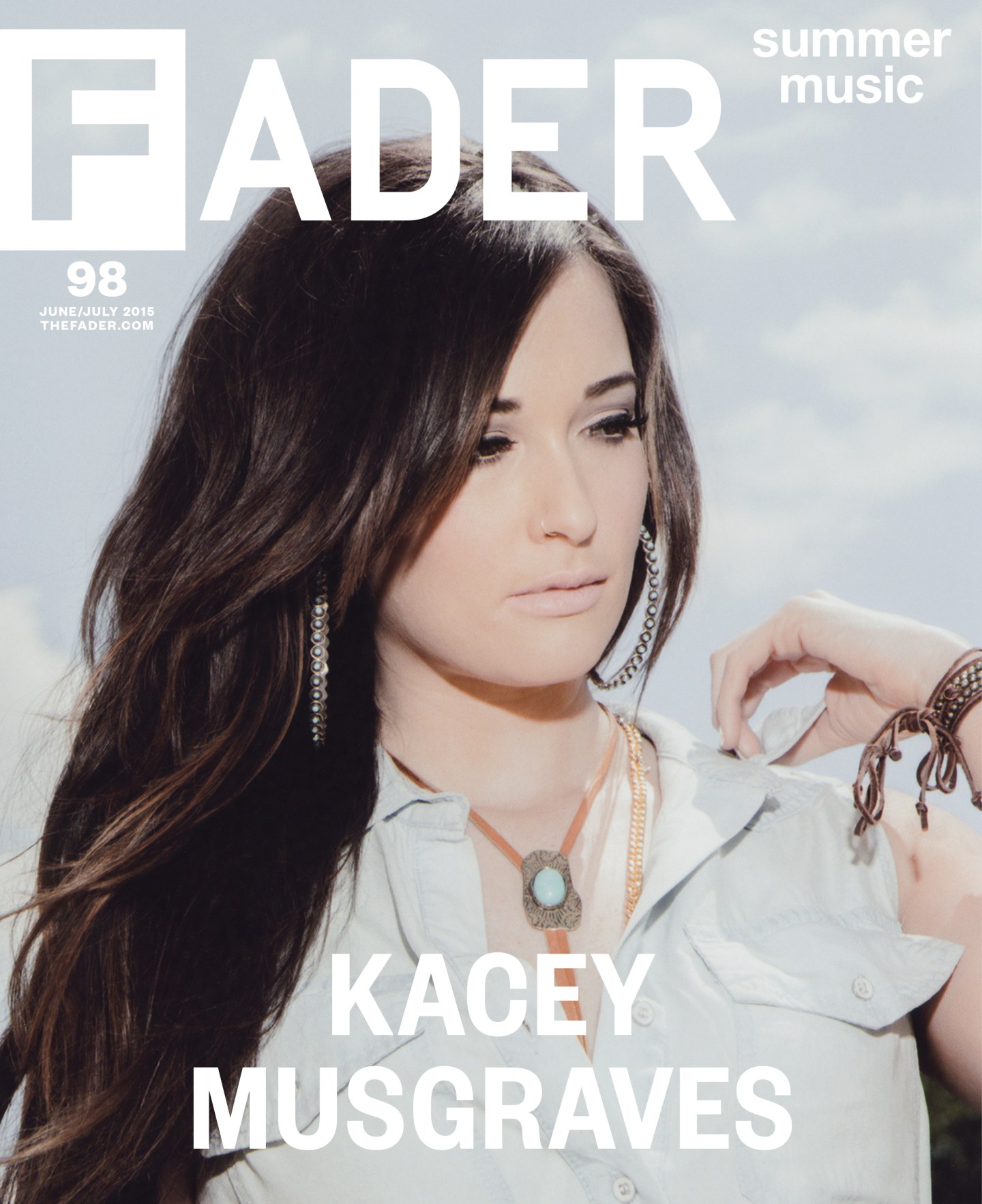

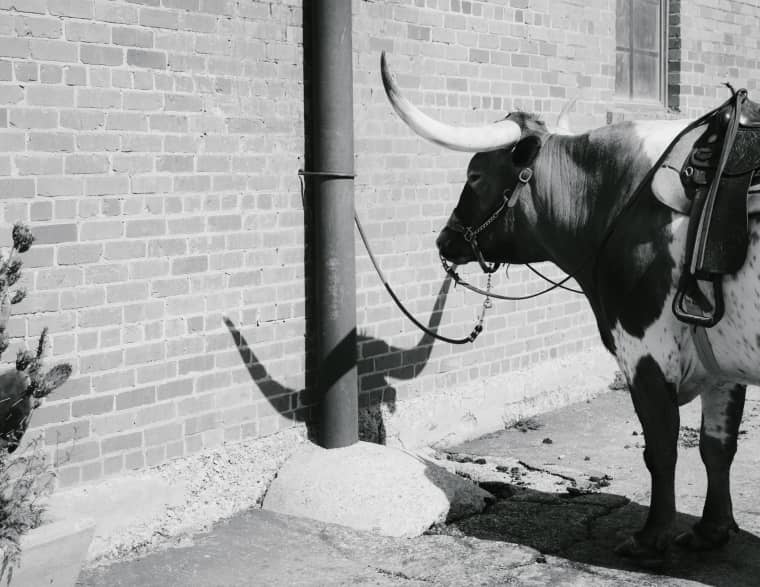

Her ongoing tour, Same Tour, Different Trailer, has been crossing the globe since 2013, and tonight it’s landing in Fort Worth, two hours west of her hometown of Golden, at Billy Bob’s Texas, billed as the world’s largest honky-tonk. “Growing up, I had Live at Billy Bob’s DVDs,” she tells me. “It’s like a thing.” Set in the historic Fort Worth Stock Yards, Billy Bob’s is surrounded daily by crowds in crisp hats and boots and an abundance of cows: plastic fat ones protruding from restaurant facades to advertise the heartiness of the steaks within, and wooden bulls hanging in the air as if charging out of second-story bar windows. The air is sweet and grassy, with a hint of barbecue. It feels a bit like Disneyland until you spot a raccoon sunning itself on a rickety footbridge, and even less so when you return hours later and realize that raccoon is dead.

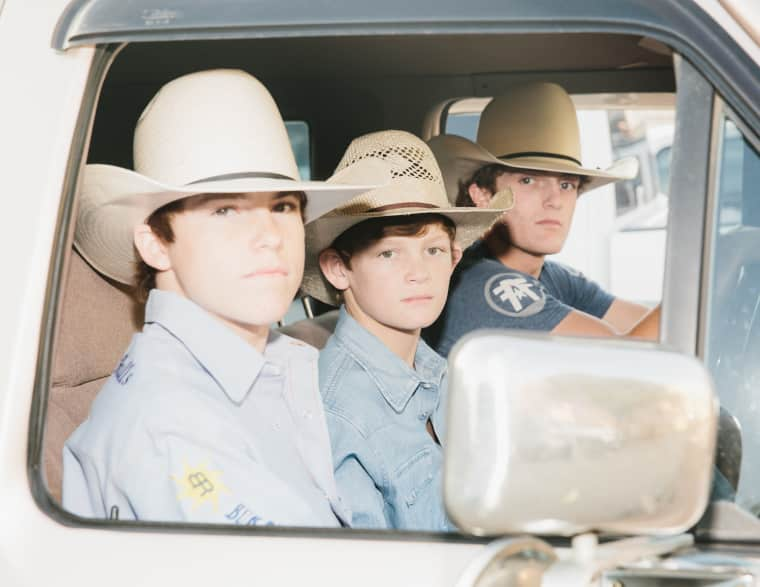

When Kacey was nine, she and her younger sister, Kelly, used to come to the Stock Yards on Sundays to sing in a kids’ band called The Buckaroos. “It was run by this group of older people that just really loved country-western music,” she remembers. “They would mentor younger kids to get out of their shells and sing old Roy Rogers songs they’d literally never know otherwise.” There was a required uniform: high-waisted blue jeans, a white button-up, a red bandana, and, of course, a cowboy hat. “I would wear my hat kind of cocked back, retro, like Dale Evans, pin-up cowgirl-style,” Musgraves says. “This other girl I would sing with would wear hers down really low, Terri Clark-style. One day, right before we were about to go sing somewhere, her mom came up to me and hissed, ‘Don’t you wear your hat like that, you’re just gonna look like some dime store cowgirl!’ I’ve always had that floating somewhere in the back of my brain.”

One of the best songs on Pageant Material draws from that experience. Called “Dime Store Cowgirl,” naturally, it recounts moments of Musgraves’ rise—from getting her picture taken with Willie Nelson to staying for the first time at a hotel with a pool—such that the idiosyncrasy of her life’s landmark events also makes clear her humble roots. It don’t matter where I’m goin’, she concludes, I’ll still call my hometown home.

At 12, Musgraves got her first guitar, and though she lacked interest in the technicalities of the instrument—“I was never going to be a shredder,” she says—she discovered a knack for songwriting. Her parents ran their own business, a copy shop called Imprints, and they indulged her interest by helping Musgraves, at 13, record and release Movin’ On, the first of three independent, old-timey country albums she put out as a teenager. “There was a local guy in Dallas who would demo songs with a studio band for, like, 200 bucks,” she says. “I guess because it was such a wholesome genre, my parents were cool with me singing and being around those kinds of places. My mom would take my picture for the CD cover, and my dad’s mom was my booking agent. She’d call places on the Texas opry circuit and say, ‘Hey, you need to have my granddaughter sing.’ And nine times out of ten they’d be like, ‘…Okay.’”

If you manage to find one of those out-of-print records—among them 2003’s Wanted: One Good Cowboy and a self-titled effort from 2007—you’ll be struck first by the amount of earnest yodeling, but also, thanks to the very presence of that founding element of country music, by the long pattern of respect that Musgraves has shown for her genre’s history, even when it’s unfashionable.

“The more country that my music gets, the less it fits into the country world today. It’s almost like there needs to be two genres, modern country and… country?” —Kacey Musgraves

One misstep regarding her bonafides came in 2007, not long after she graduated high school, when she appeared on the USA Network’s ill-fated reality singing competition Nashville Star. “I didn’t really know what I was getting myself into,” she remembers. A friend of the family had helped arrange a private try-out, so she could bypass the cattle call of a general audition. “I was like, ‘Cool, might as well do it,’” she says. She was booted after the third episode, coming in seventh. “I’m glad that I got voted off really early, because hardly anyone remembers it. I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t know shit. And musically, I didn’t make great choices.”

But there were upsides to the experience: during her brief time on the show, she met a few people who were working in Nashville and soon followed their lead, moving to the music capital to pursue a solo career supplemented by songwriting for others. At 21, Musgraves signed a publishing deal with Warner/Chappell and started working as a staff writer, writing for other artists nearly every day, until she felt confident enough in her style to set aside songs for herself. Learning the limitations of her voice—more coffeehouse-calm than most country stars—helped too. “When I realized that I didn’t have an acrobatic, powerhouse voice, I think it made my songwriting better. It made me focus on the lyrics more. It’s not about what I can do with my voice; it’s whatever the song needs.” She started playing solo acoustic sets around town, until Warner, seeing potential, helped arrange for a three-piece band.

One of its members was Misa Arriaga, a Mexican-American multi-instrumentalist from Jasper, in East Texas, who’d spent the past decade kicking around Nashville. “I was getting so jaded about the state of country as a genre and a business,” he remembers. “If Kacey hadn’t come along, I probably wouldn’t be in country music. I remember the first time I heard ‘Merry Go ’Round,’ I was kind of offended because it hit so close to home, like, ‘This is me; this is my hometown!’ But that’s country music. The honesty of that is country music.” When their shows started going well, Musgraves asked Arriaga to be her bandleader, and he set about hiring a full band capable of reviving a classic country-western sound, with slide guitar and standup bass and players dressed in suits. “We both agreed that we didn’t want a band with people who knew current country music at all,” he says. “I’d seen enough to know that wasn’t her trajectory.” Somewhere along the line, the two started dating. “We just kind of became best friends,” Musgraves says. “It was cool that we had a chance to really get to know each other before everything kind of got crazy.”

Misa Arriaga and Kacey Musgraves

Misa Arriaga and Kacey Musgraves

At 5PM in Fort Worth, backstage at Billy Bob’s, Arriaga can be found steaming Musgraves’ cowboy hat. Everyone in her band wears one. Kyle Ryan, a long-haired Berklee grad from Nebraska, strums an unplugged electric guitar; he looks like a country hipster in vintage red Nikes and Native American-print socks. Adam Keafer, the thickly mustachioed bassist, says, “Hey Kyle? Did you hear Tesla is coming out with home batteries? Now you can really go off the grid.” The band passes around a pink lawn flamingo, signing it, dating it, and writing messages; it’s become a tradition, and at every gig they toss another bird into the crowd.

The venue tonight is massive, with a ring for bull-riding, chairs for boot-shines, and multiple hardwood dance floors, including one with a bejeweled saddle hanging from the ceiling like a honky-tonk disco ball. Lining the walls of the back-corner barbecue restaurant, and all around the venue, are cement panels preserving the hand prints and signatures of artists like Lee Ann Womack, David Allen Coe, and Loretta Lynn—an honor reserved for those who’ve sold out the place. Add to that list Kacey Musgraves. Backstage, she presses her hands into a wet cement mold, then, using the point of a pencil, etches zigzags around the border and cactuses in the bottom corners. Few of the other artists recognized included their bands; she asks hers to add their initials, then, grabbing the taxidermic armadillo that’s become something of a tour mascot, pushes in its paw prints too.

Tagging along this week is another of Musgraves’ closest collaborators, Shane McAnally. Country music is a great place for songwriters like Musgraves to break out as solo acts, but it’s also a place for failed solo acts to break out as songwriters; that was the case for McAnally. Now 40, he moved to Nashville as a teenager and released a single, self-titled album. “I tried to be an artist for so long,” he tells me, “and I tried so many other things and thought, ‘Is it because I’m gay? Is it because of this or that?’ And the truth is it just wasn’t the right set of people.” By 2011, when he met Musgraves through a mutual friend, he was finally beginning to find some success writing one-off country songs for other artists. “The first time I met Kacey, we actually wrote a song that’s on the new record,” he says, referring to its slow-waltzing closing track, “Fine.” “I wasn’t a producer at the time, and I went home and told my partner, ‘I met a girl tonight, and if I was ever going to make that leap [to produce], I wish that it was with her.’ I’d never been so hit in the face with somebody just sitting there with her guitar, singing things back to me. I was just like, ‘This is the combination of every artist that has formed my musical path. From Lee Ann Womack to Willie to Dolly, the people that I have been obsessed with, they’re all rolled up right here in Kacey.’ It’s not what’s on the radio right now, but I would like to think that we’re working to change that. Those choruses, and the way she sings? It’s all right there, the singalong-ability of commercial pop songs of all of our history.” Around the same time, Musgraves met another Nashville songwriter named Luke Laird; she introduced the two men, who’d go on to produce both of her albums and, in various configurations with McAnally’s friends Brandy Clark and Josh Osborne, get co-writing credits on nearly every Musgraves song.

Unlike many of the artists that her braintrust also writes for—and collaborating successfully on Same Trailer seems to have only expanded their business with big names—Musgraves was never concerned with being on the radio. “There was this cycle in Nashville where if you were a girl, you had to be really sassy: ‘You cheated on me, so I’m going to burn your house down,’” she says, seeming to refer to Miranda Lambert and Carrie Underwood, two of the only women that get consistent country radio play these days. “I’ve never felt a kinship to those kinds of songs. I love John Prine, his witty turns of phrase. I love Glenn Campbell, Marty Robbins, Loretta Lynn. There was this really imaginative and whimsical period of country music where instead of trying to match a trend, people became popular because they were unique. There wasn’t a basket of four subject matters. The more country that my music gets, the less it fits into the country world today. It’s almost like there needs to be two genres, modern country and… country?”

What makes songs like “Merry Go ’Round,” “Follow Your Arrow”—and now “Dime Store Cowgirl” and “Pageant Material”—stand out within the context of present-day country is not, as some have suggested, the contrast between Musgraves’ proudly unpolished, liberal-seeming ideals and some red-state, buttoned-up notion of the genre. There were always country stars who smoked weed and lived free. It’s just that they’ve been few and far between these past 40 years, filed safely away from the limelight in subgenres like Americana. What makes Musgraves exceptional is that she’s a core artist on a modern-day major label singing this way. Her heritage sound and honest lyrics accurately position her as a vulnerable outlaw, a millennial with the rugged individualism of the best artists country has ever had to offer.

The country music industry is peerless in its ability to absorb renegades into its business model. When Musgraves began recording Same Trailer, Different Park, it was for the boutique label Lost Highway, founded by Luke Lewis, the chairman and CEO of Universal Music Group Nashville. With more commercial endeavors focused elsewhere, Lewis used the label to support singer-songwriter types and happily ceded full creative control, Musgraves says. But just before her album was finished—and after it was too late to change—he retired and shuttered Lost Highway, and she upstreamed to Universal’s more commercial Mercury division.

While Musgraves’ message on Pageant Material may be to disavow the politicking incumbent of major-label musicians, the label has certainly done well on her behalf. Whether it’s for award judges or audiences, they’ve correctly identified an opening in the marketplace for an artist with a rootsy, retro, self-made style—a style that their own actions have created demand for by filling the airwaves with Musgraves’ glitzy opposites. When she and her band say they don’t listen to modern country, they’re just a few listeners among millions uninterested in chart-toppers like Luke Bryan and Sam Hunt—guys with sloshy party anthems and synth tracks that contort the genre away from its core, not to mention record deals with Universal subsidiaries and even songs written by Shane McAnally and Luke Laird. Musgraves, like many a twentysomething, is navigating an economy she’s been born into, and knows she’ll have to make compromises in pursuit of her art. Her tour bus currently sleeps 11, and she says she’d love to add a lighting director, to put on a more consistent show. In order to do that, she’s going to need a bigger bus, and in order to afford a bigger bus, she’s going to need to do more than sell out Billy Bob’s.

“The idea of massive amounts of fame—having my face on Walgreens end-caps and pizza boxes—I don’t fantasize about that. I’m happy with just being a songwriter. I’d rather have smaller numbers [of fans] that are really into what I’m doing than a massive amount of people that don’t really know what I’m about.” —Kacey Musgraves

How that will happen isn’t exactly clear. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, but sophomore albums face high expectations for artistic growth. Pageant Material is another outstanding collection of songs, but it doesn’t push Musgraves’ concepts much further than the first album did. Her sound’s mostly the same, with a bit more steel guitar, and the defining traits of her songwriting remain its cleverness and emphasis on self-acceptance. Being pegged early as an artist with a social agenda could be an obstacle, especially if her liberal fans expect her to develop her politics any futher to the left. That’s a risky move in country—look where criticizing Bush got the Dixie Chicks—but more importantly it’s not something Musgraves seems concerned with doing. “I’m definitely for people deciding things for themselves, what they do with their own bodies,” she says at one point. “As little policing as possible, I’m cool with. I hate what they do with our food, the quality of produce that people have access to, especially in poor areas. But I don’t think I’m informed enough.” Rather than change too much, she’s keeping the scale of her music comfortably small.

There’s a line on Musgraves’ new album, on a song called “Good Ol’ Boys Club”: Another gear in a big machine don’t sound like fun to me. It’s a classic Musgraves move, layering new meaning on a cliché phrase. In this case, she is referencing Nashville’s Big Machine, a powerhouse label built around the discovery and lucrative evolution of Taylor Swift. “I’m talking about a lot of different people,” Musgraves tells me, when I ask about the double-meaning. “Any industry has its shoo-ins and people that get in because they know somebody, or their dad worked here, whatever. But, yeah, there is a wink.” Swift—one year Musgraves’ junior, the blonde to her brunette, the Yankee transplant to the taxidermy-wielding Texan—used to be more of a direct competitor than she is now that she’s openly left the genre to go full-on pop. (Both of Musgraves’ Grammy victories were over Swift.) “The idea of massive amounts of fame—having my face on Walgreens end-caps and pizza boxes—I don’t fantasize about that,” Musgraves says, referencing some of Swift’s recent album promo. “Do I want to be comfortable, to live my life however I want within reason? Yeah. But I’m happy with just being a songwriter. I’d rather have smaller numbers [of fans] that are really into what I’m doing than a massive amount of people that don’t really know what I’m about.” When asked what kind of artist she aspires to be, she names Alison Krauss, the bluegrass veteran. “She’s managed to maintain her privacy and her sanity, so it seems, and her witty sense of humor,” Musgraves says. “She’s never wavered from where she started out. She’s got, like, 27 Grammys, and she hasn’t been beaten into the ground. I’ve never heard anyone say they’re sick of Alison Krauss.”

Still, when Katy Perry invited Musgraves on tour in early 2014, and CMT announced that the pair would co-headline a TV special, the news produced, in me, a familiar cringe. Would Musgraves’ successful country career, like Swift’s, turn out to be a trojan horse to break into something even bigger? No, it seems: onstage she wore the same boots and fringe, brought along the same band and the same fluorescent cactus backdrop, sang the same, was the same. Two months after the Katy Perry shows, she went on tour with Willie Nelson. In that move lies all of her potential. For her record label, surely, the vision is that some combination of Musgraves’ songwriting, style, sound, and position in the broader musical landscape will guide her, without needing any songs produced by Max Martin, into the heart of the mainstream. For Musgraves’ fans, the even wilder dream is that, after that, a better country mainstream might coalesce around her, and her exception will become the rule.

The morning after the show in Fort Worth, following an overnight drive of 300 miles south, Musgraves and the crew on her bus awake to the sound of a marching band, as the town of Helotes’ annual Cornyval parade passes just outside their window. McAnally pops his head out first and waves, then someone in the band sticks out the armadillo, like it was waving too. As murmurs spread through the crowd that Kacey Musgraves might be in there, she emerges, beaming in oversized sunglasses. Some time after the parade passes, she and Arriaga change into running clothes and head out together for a pre-show jog.

Helotes is an old Texas hamlet with an outdoor market of junky antiques, Adirondack chairs, and tents where women sell Mary Kay. It’s the sort of place Musgraves likes to sing about, a town “too dang small to be mean,” as she puts it on Pageant Material’s “This Town,” even though the track opens with a recording of Musgraves’ real-life “meemaw” telling the story of a hospital patient with a drug overdose biting the attending nurse. The night’s venue, Floore’s Country Store, has been standing there for 70 years, with a cinderblock bar and an outdoor stage that only real-deals would ever pass through to play. The venue is dotted with sturdy trees growing through breaks in the pavement. It’s where she first opened for Willie.

During the show, as stars form webs in the open sky, I climb one of those trees to get a better look. On “High Time,” from the new album, there’s a yippie ki-yay whistle, and hearing it under the full moon in Texas, I feel a profound, timeless calm. The show is all-ages, and I notice, standing on a curb some way to stage left, a curly-haired toddler dancing in a family-made T-shirt that reads “Follow Your Arrow.” Maybe it’s hoping too much to think Kacey Musgraves might somehow save country music, but for the sake of this girl and the world she’s growing into, she sure won’t hurt.