With Beyoncé as their shepherd, twelve black men wearing white suits took to the Grammy stage, put their hands up, and asked America not to shoot. In a complete 180 from last year's performance of "Drunk In Love" with Jay Z, Bey slipped into a celestial white gown and delivered a stunning interpretation of the gospel standard "Take My Hand, Precious Lord." The song, which is sung in Selma, by Ledisi as Mahalia Jackson, was structured as an introduction to John Legend and Common's performance of "Glory," also from the film.

Though Beyoncé is increasingly forthcoming with her politics, more vocal about her views on racial justice and gender equality, this particular moment, on one of the most sterile stages in the world, may be Beyoncé's most political yet. In a video introducing the men she invited to stand with her, she explains her performance as an expression of collective pain. "I feel like now I can sing for [my father's] pain," she said. "I can sing for my grandparents' pain. I can sing for some of the families that have lost their sons." She did not have to explain what she means by that last sentence.

Earlier in the show, during a manic, multilingual, Hans Zimmer-assisted rendition of "Happy," Pharrell attempted something similar. His backup dancers were dressed in all-black, with hoodies pulled snugly over their heads; he gave the mawkish song a darker vibe than its recorded version. Pharrell's crew, too, put their hands up and asked America not to shoot.

Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images

Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images

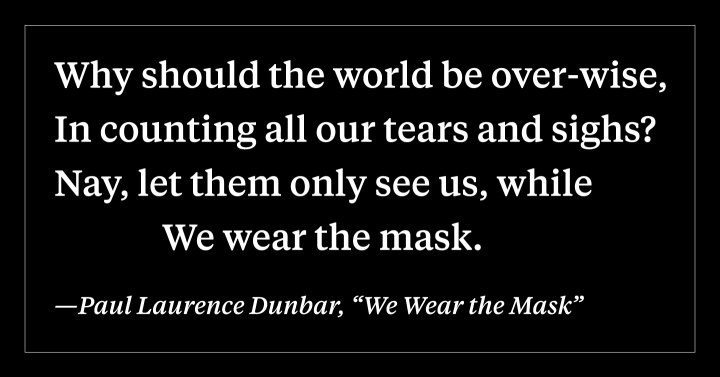

Beyoncé and Pharrell appeared at the Grammys as individuals, with their own motives and ambitions and raisons d'être, but the implied pronoun stringing their performances together was a collective "we," a "we" signifying black folk. Whether or not theirs were meaningful acts or hollow statements is debatable—who among us will forget Pharrell describing himself as a "new black"? But that these artists were responding to a gravitational pull to "we" seems clear.

In the introduction to

Black Prophetic Fire, Cornel West's recent tome on the disappearance of a collective black consciousness, he writes, "The fundamental shift from a we-consciousness to an I-consciousness reflected not only a growing sense of Black collective defeat but also a Black embrace of the seductive myth of individualism in American culture. Black people once put a premium on serving the community, lifting others, and finding joy in empowering others … Black people once had a strong prophetic tradition of lifting every voice."

West refers, of course, to a specific kind of prophetic tradition, embodied by leaders like Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and Ida B. Wells, all of whose lives prioritized the "we" over the "I." But, though they are not leaders in the manner West describes, I couldn't help but see some we-consciousness on that Grammy stage.

It had occurred to me earlier in the week, too, when I went to the opening of the Art Gallery of Ontario's Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's The Time exhibit. Opening night is never the ideal time to see art, I remembered, as I listened to a woman authoritatively tell her group of friends that Water-Worshipper, an intense piece with explicit references to the common "we" of slavery, colonialism, and Yoruba tradition, "must have just been a filler piece with no real point." Just to the left of the piece is this quote from bell hooks: "To see and understand these paintings, one must be willing to accept the tragic dimensions of black life."

Mike Coppola / Getty Images

Mike Coppola / Getty Images

I thought of "we" still when Kendrick Lamar dropped "The Blacker the Berry," ostensibly the second single from his still-untitled forthcoming album. In an alternate universe, the song's beat, produced by Boi-1da, would underscore a boastful, bellicose Drake. But in K-dot's world, it serves as the backbone of an exhortation to do something, anything about what a century ago was termed the Negro problem.

My hair is nappy, my dick is big, my nose is round and wide

You hate me don't you?

You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture

You're fuckin' evil—I want you to recognize that I'm a proud monkey

You vandalize my perception but can't take style from me

It goes on like that for three elegiac verses, with respite from Kendrick's growl coming in the form of a hook from dancehall classicist Assassin and, eventually, a jazzy outro courtesy of Robert Glasper. But what the hell is Kendrick talking about? I'm not sure entirely, but I do know who he's talking about: we.

Interpretations of the song keep rolling in; some are more sophisticated than others, a few are likely closer to his intended meaning than most. But more than what he says, it's Kendrick's commitment to talking to us that has stirred our emotions. His jagged insistence that he loves himself, i.e. that we love ourselves, in the face of what he describes as "evil" is what strikes the most thunderous chord. It's warm in his black embrace, and that's what matters right now.

Minutes after the song dropped, I knew exactly what a friend meant when she texted to say, "We needed that."

Lead image: Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images