HBK Gang Protect and Promote the Bay’s Melting Pot Culture

From the magazine: ISSUE 90, Feb/March 2014

Couples sip wine on the balcony of Oakland’s The New Parish as Iamsu! lumbers in. Standing six-foot three, with a bonsai-sprout afro, the rapper/producer poses for photos with fans and childhood friends. The DJ plays one of his songs, “100 Grand,” and a silver-haired guy near the stage resolutely jerks around to it, dancing like a hippie at Burning Man. Pulled from one of his three 2013 mixtapes, “100 Grand” is a ’90s Cash Money-indebted, steadily thwacking track dotted with guest of honor Juvenile’s guttural wooooaahhs. The song’s a carefree brag, with Su acting out but aiming to inspire: Mad pussy, young niggas getting money now, he raps, just after praising himself for being genuine enough to attract authentic friends.

Su, born Sudan Ahmeer Williams and now 24, has made the half-hour drive down from Richmond, the North Bay suburb where he was born, for a performance by his cousin, Mani Draper. In many ways, Su’s journey to here really kicked off nine years ago, when Draper was the captain of Pinole Valley High’s varsity basketball team and introduced him to two fellow players, both also producers: Chief, who got his nickname from dancing at American Indian powwows, and P-Lo, a Filipino kid who wore flashy hand-me-down Polo to school. Later, the three would join with P-Lo’s older brother, Kuya Beats, to form a production crew called The Invasion, and around it, a collective of savvy misfits known as HBK Gang, the acronym short for Heart Break Kids.

At the club in Oakland, Draper’s sisters swarm him as he finishes a hard-spit set, and Su slips around the corner to join Chief and another HBK member at a teenage girl’s birthday party, where P-Lo has agreed to perform. Su sparks a joint, pleased with himself as the act goes unnoticed by two cops lingering nearby. Jumpstarted by the influx of tech money in nearby San Francisco, downtown Oakland is developing quickly; a few doors down, the historic Fox Theater has reopened after a 39-year closure, and the party is being held at a new gallery space across the street from a bar with shuffleboard. The owner stands outside, anxiously eying underaged attendants in Tumblr-approved fashions—white fur and cropped denim, dreadlocks and septum piercings—as one partygoer remembers aloud that someone was shot dead on this corner after a Gucci Mane concert a couple years ago.

Inside, P-Lo performs in the thick of a mob of wobbling girls, a cup in his hand and his tongue flopping out as he raps, Three white hoes/ I’m a giant in my city like fee fi foe. After he finishes his song, the apply-yourself anthem “Going to Work,” he scrambles onto the sidewalk where Su and the crew have been waiting. They’re without coats on a pretty cold night in the Bay, energized by chugged beers and some weed a guy delivered to another HBK rapper’s mom’s house in a Starbucks pastry bag earlier that day. Mostly in their early 20s, but buzzing with adolescent energy, they take turns running in tiny circles, picking up the speed to jump high enough to smack a street sign.

Above: Iamsu!

Today’s HBK Gang started to take shape in 2007, when The Invasion combined with another group of friends—Kool John, Jay Ant and Skipper—at Contra Costa, a community college in San Pablo. Their alliance was largely conceived by Iamsu!, who envisioned an audience for rap by Bay Area kids who didn’t neatly fit the archetypes of gangsters or skaters. “I think we’re all secret nerds,” Su says. “We like random shit and we’re not afraid to talk about it, so we all gravitated toward each other.” A quarter-century after San Francisco’s “People’s Station,” KMEL, became the country’s first pop channel to regularly play hip-hop, HBK is black, Asian, Latino and American Indian—mixed through and through. On a whiteboard in P-Lo and Kuya Beats’ home studio in nearby Pinole, someone has scrawled “Hella Brown Kids,” an alternative HBK definition that’s a joke, but a fitting one for a uniquely diverse crew in a uniquely integrated city.

Su and Kuya Beats both learned production at Youth Radio, a nonprofit where after-schoolers are taught to see music as a cultural language as well as a professional skill. The pair’s former mentor there, the producer Trackademicks, explains Youth Radio’s homegrown philosophy: “You can’t separate cultural context from what’s going on musically. Whatever is going on with the people is what’s going on with the music.” Fittingly, Su and Kuya’s time there, from 2004 to 2006, coincided with a bright period for the Bay’s hyphy music, rich with independently released club records that countered escalating violence with a cartoonish embrace of party culture. Hyphy’s stop-and-go, scrunch-faced beats and lyrics championing neighborhood unity rallied the city and attracted national attention—and influenced HBK—but the motivational messages were undercut by some of its stars’ goofy, ghostride-the-whip antics. “People were doing interviews with big-ass glasses, talking wobbly and crazy. That’s not how people act out here,” Su remembers, raising an eyebrow. “This is a real place, it’s not Six Flags.”

In the beginning, HBK’s home base was a humble, bi-level crash pad near Contra Costa, where Chief was living with his cousins. The crew built a makeshift studio in the basement, decorating it with thrift shop paintings and recording before and after class. Leaving at night, they’d tiptoe around children sleeping on the floor upstairs. If that house was their first lab, their music’s first testing grounds were recurring parties called Shmops, held at the Richmond home of Kool John’s mom on weekends when she went out of town. There’d be a swarm of teenagers dancing in the cozy living room while new HBK songs played and an enormous mound of their shoes piled at the front door, to protect the carpet.

Over the years, the squad has grown steadily. Now a sprawling 17 members, with no official leader, HBK’s ranks include Dave Steezy, who Kuya Beats affectionately calls their “super hipster,” as well as rappers CJ and Azuré, a singer named Rossi, three video directors, two marketing/management guys and the gang’s latest addition, Sage the Gemini, a 21-year-old rapper and producer with some hundred-million YouTube views to his name. Sage joined in late 2012, after convincing Su to record a guest feature for “Gas Pedal,” a song he’d produced in his bedroom. “I pick Su over Tupac and Su over Snoop,” Sage says, a fan before the two had met. “I mean, I’m kinda younger. I got respect for the big homies, but Su over everybody, HBK over everybody.”

“We found that middle ground where we can fuck with everybody.”

—P-Lo

P-Lo and Kuya Beats.

Meticulous and self-assured, “Gas Pedal” is a particularly tidy example of HBK’s economical but freewheeling take on rap, where instrumental noodling is always grounded by a dominant bass line. Though presumably about speeding up, the song insists on going slow, sprinkling iced minor chords and gasps over pristine open space, like the Pacific spread wide. While some young artists collage existing aesthetics, the members of HBK distinguish themselves by taking on the considerably more difficult task of developing their own style, drawing from their colorful regional roots and collaboratively tailoring them. That Bay-first approach defines their collective personality, too: HBK takes pride in having fun and working together, because that’s Bay culture.

Like all new additions, Sage was approved after HBK’s four founding members—Su, Chief, P-Lo and Kuya Beats—convened a “tribal council” with in-house manager J.R. and voted. “You only really need someone on the team when the energy works,” Kuya explains. P-Lo likens HBK to a successful basketball squad: “I’ve always known sometimes to play the back, or that sometimes I gotta take the lead. Su isn’t always on his game, so someone’s gotta pick him up. I’m not always on my game, so Kuya’s there to pick up the slack. Everyone in HBK is hella accountable—that’s what makes us who we are. When there’s so many people involved in one thing, there’s no way that it can’t be good. We found that middle ground where we can fuck with everybody: suburban skater kids fuck with it, just like the hood folks fuck with it, cause it’s slapping.” Now that HBK could fill a classroom, it appears they’re always celebrating someone’s birthday. Around each other, they rarely pass five minutes without dancing, their shoulders falling backwards into a wobbling Bernie, the late-’80s play-dead dance they’ve repopularized. To strangers, they are gracious; when a girl falls at a party, they’re the first to offer a nonjudgmental hand.

Sage the Gemini at home in Fairfield, CA.

The studio HBK rents in industrial Emeryville, near the foot of the Bay Bridge, is small, with wine-colored walls and a tiny Christmas tree blinking in the corner. When Sage the Gemini walks in, he appears to float. Tall like Su, with striking green eyes and the stocky but trim build of a mixed martial arts fighter, he has become a teen heartthrob. At the studio, HBK manager Will Bronson reads aloud an email from a high school senior who asks if Sage can be her prom date. “People really think I’m like an asshole,” Sage says. “They think I’m cocky, that I can pull any girl. I might be cute, but I’m still a nerd at heart. I can’t walk up to a girl unless I’m playing.”

Sage signed to Universal’s Republic Records last summer after the enormous success of his song “Gas Pedal” and its follow-up, “Red Nose,” now platinum and gold singles, respectively. He’s the only HBK member with a traditional major label deal, and it’s easy to see why executives would be drawn to him first. Sage has the conspicuous presence of a Disney child star: he dances and does voices, compulsively breaking into a character when he’s joking or nervous that sounds like a cross between Miss Piggy and Kermit. His songs have a carnal directness, but they’re untarnished by actual filth, and Sage has an ease that megastars like Justin Bieber—who rapped a verse on an official “Gas Pedal” remix—aspire to.

But unlike Bieber, a teen hell-bent on sullying his own image as he stumbles toward an adult chapter of his career, Sage is actually squeaky clean. He doesn’t drink or do drugs, though he tried both at a young age while growing up poor in the notoriously marginalized San Francisco neighborhood Hunter’s Point. “I always did my own thing, that’s why people didn’t really click with me,” Sage recalls of his childhood. “I stood out. People thought like, ‘He’s a stinky kid, doesn’t have a lot of money, but he’s got a cool personality.’” As a preteen, he begged his mom for a video-enabled karaoke machine; after his family moved to Fairfield, an outer suburb of the North Bay, Sage got a computer mic and made a song about Myspace that went viral. At school, though, he was less popular: “Girls having crushes on me? That was a no. Me hanging out with a lot of people after school? No.” These days, he’s embracing idol status like he’s getting revenge on those who once ignored him, posting videos of his ab workouts and ripping his shirt off at shows.

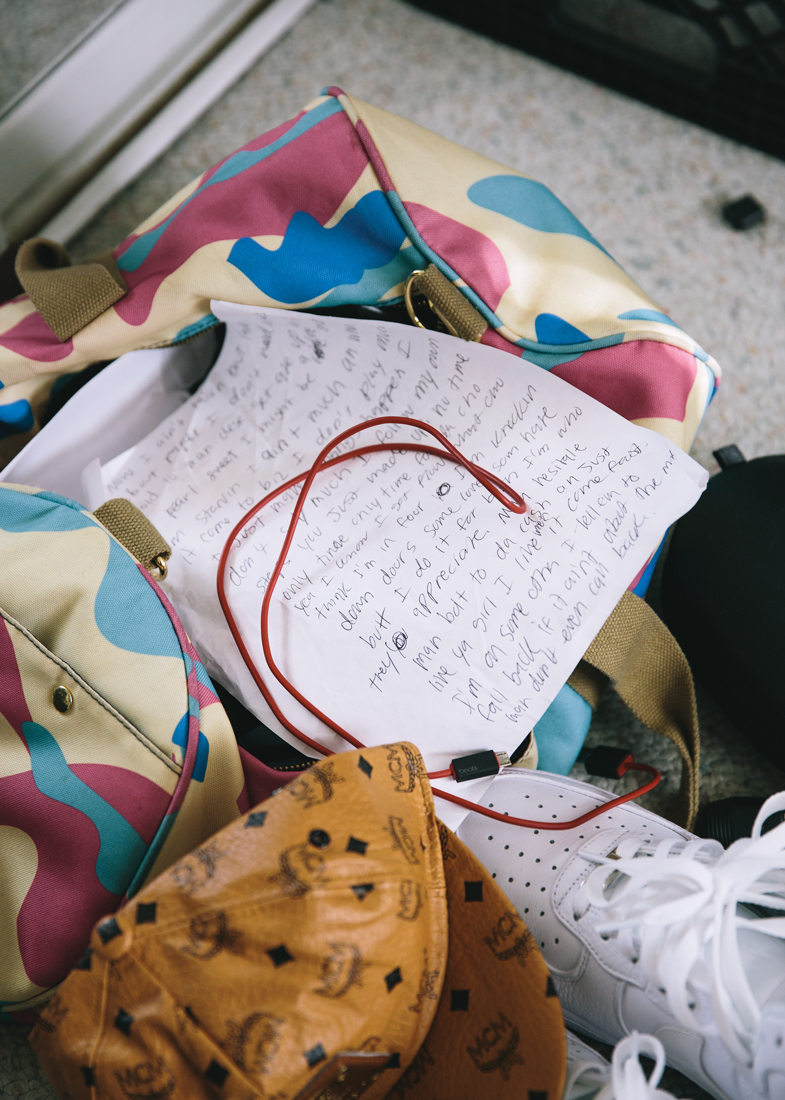

At HBK’s crowded studio, when Sage climbs on top of Kool John and Rossi to edge himself into a measly slice of a couch, no one challenges him. Over the course of the evening, some 25 people pass through, progressively covering the floor with plopped-down backpacks. Febreze is sprayed and conversations overlap. Over in a corner, CJ records a verse but everyone focuses instead on the fact that his short braids make him resemble Afeni Shakur, Tupac’s mom. A TV in the corner plays a nature documentary about butterflies. “We watched all the predator ones,” Su tells me. “Wings of Life? That shit was hella raw.”

Top right: Rossi and Iamsu! pose for a photo with a fan. Bottom right: Kool John. Bottom left: Chief.

The session has the feel of an alternative college for bright kids who want to learn together by doing as they please. Sitting in the engineer’s chair, Su seems loosely in charge. When Kool John asks if he should prep a verse, Su diplomatically replies, “You can if you want, but you don’t have to.” For what feels like an hour, everyone listens to a looping sample of D’Angelo’s “Alright” that Su may put on his new album, Sincerely Yours, which he hopes will transport restless kids to a calm, solitary place where “it feels like there’s milk in your eyes and milk in your head.” Pointing out a funky lick, he says, “I’m gonna play this bass myself.” Su only knows the instrument a little bit, he explains, but teaching himself won’t be hard.

Emboldened by Sage’s success—or maybe just years of touring, dating and growing up—Su has big plans for the future. During my visit, he signs a major distribution deal and prepares for a session with a physical trainer. “Ten million records—I really see myself doing that,” he says. “But [HBK manager] Stretch said nobody’s ever sold 10 million records without taking their shirt off. I feel like if I had a six-pack, I’d damn near dominate the industry.” As a producer or featured rapper, he’s already landed a handful of singles on the radio, but Su sees himself as being more like Oakland hometown hero and shirt-wearer Mac Dre, the rapper who was presciently “2 Hard 4 the Fuckin Radio” back in 1989 (and who was gunned down in 2004, when Su was 15). “Dre cultivated his fan base, and [his independent label] Thizz sold millions of records,” Su says. “He was in control of his own destiny.” But unlike Dre, Su wants to have his cake and eat it too, getting a big-business boost while remaining independent. With his new deal, under which the Warner Music Group-owned Alternative Distribution Alliance will promote his album, he’ll be in a similar position to Macklemore, maintaining creative control but with an industry edge to get his music into stores.

After Su signs his deal, HBK’s two biggest stars briefly part ways. Su makes a celebratory, one-night trip to Vegas, and Sage heads to New York to tape a BET New Year’s Eve special, then flies back to California the same day. The pair converge again in Los Angeles, at a hotel where Power 106 is putting them up in anticipation of Sage’s performance at the station’s annual Cali Christmas concert. It takes 20 minutes to drive to the venue, Anaheim’s Honda Center, which makes Sage carsick. In the van, he wonders aloud if strangers in the neighboring cars have traveled to see him. He’s dressed like a junior pastor, wearing silver trousers, a star-printed sweater and glittering sneakers, and has brought along Su, his DJ Lucci, four backup dancers and Stretch. Once backstage, among the likes of Kendrick Lamar, B.o.B and their supporting staffs, the HBK contingent is by far the loudest and most animated. It’s hard to say whether this is because they’re generally the youngest, or just the most fun.

Originally, the promoters had hoped Sage would join three LA artists—TeeFLii, Ty Dolla $ign and DJ Mustard—onstage in a medley of “Young California” acts. Spend an hour listening to rap radio anywhere, and you’ll hear there’s currently a large appetite for California’s joyful party music; right now, Mustard is seen as its leading purveyor. Over the past two years, he has produced a number of national hits in a style he calls “ratchet,” marked by skeletal, plinking beats and coveted by artists from both coasts—not least among them Jay Z, who recently hired him to soundtrack his Barney’s store pop-up. But HBK feels Mustard lifted that sound partly from the Bay, sans attribution. They talk candidly about his making a trip to town and asking P-Lo for drum samples, and say Mustard once borrowed liberally from the melody of “I Bangz,” a 2009 song by their friend Young Bari. “Some people out there right now are influenced by us but don’t really want to say it,” Sage says with tempered agitation. “If you went to the Bay Area, slept there and got a dream there, don’t try and sell that dream back to me.” At Cali Christmas, Sage refuses to share the stage, opting for the opening slot instead.

“If I had a six-pack, I’d damn near dominate the industry.”

— Iamsu!

That night, DJ Mustard perches in the wings as Sage performs for a half-full arena. Live, Sage’s voice leaps away from its restrained, recorded monotone. His dancers’ toes rarely settle on the ground; when they’re done, one of them has somehow ripped a huge hole in the front of his pants. There’s a distinct looseness to HBK that stands out against Mustard’s more rigid, clean productions, and there’s a warm spirit to the guys making it. If this is party music, you’d probably rather invite HBK to one of yours. Immediately after their set, as Mustard takes the stage, Sage and his team are abruptly shooed out of the stage area—not by Power 106 staffers, but by people who Sage identifies as Mustard’s personal security team.

Driving back to the hotel before dinnertime, Sage and his dancers take stock of what it was like to play a 14,000-seat venue. Dancer D-Mac says, “I couldn’t tell.” Sage is similarly underwhelmed, and clearly antagonized by Mustard’s move with the security. “I ain’t doing shit like this no more if we go first,” he tells Stretch, deflated. “Fine,” Stretch says. “Make more than two hits, then you won’t have to perform first.” He sounds forceful but friendly, like a dad. Sage glances out the window and rubs his forehead. “So we’re gonna have to work harder then,” he says. “But I’m not going first no more.”