For over three long years, Clipse have been forced to hold the lid shut on a Pandora's box full of remorseless anger and piles and piles of cocaine.

January 2014: Pusha T seems to have confirmed rumors that, after a five year hiatus, Clipse will reunite for a new album. Today, we take a look back at their masterwork Hell Hath No Fury, in this FADER feature from 2006.

From the magazine: ISSUE 36, March 2006

“Super… Producer…” sighs Malice, one half of the fraternal rap duo Clipse, the words practically dripping out of his mouth. Malice is sitting in the backseat of a BMW SUV—a carton of Chinese take-out on his lap—waiting in the parking lot of Virginia Beach’s Hovercraft Studios for Chad Hugo to arrive. Pusha T, Malice’s younger brother and the other half of Clipse, arrives at the studio shortly after Malice, and it’s immediately apparent that he’s the driving force of the duo; he answers questions first, sets the agenda for the day, gets the most excited and the most angry in the course of our conversation. The two greet each other with a pound, a “S’up, fam,” and then recede from one another. Presently, Pusha is milling around outside the car with his cell phone attached to his ear, and Malice is sitting and waiting, making it clear that he’s used to being on pause, stranded in Neptunes time. “I wonder how many days, months of my life I’ve spent waiting for these guys to show up,” he says with a smirk.

In rhymes, Pusha and Malice create a finely detailed world of drug dealing, a place where all the snow on the concrete is Peruvian and they are yellow-bottle grippers, decked out in full-length chinchilla coats and blinding watches. But right now they’re just some dudes standing around in a parking lot in the suburbs.

Hovercraft is owned by the Clipse’s longtime VA running-mates the Neptunes—made up of the low key Hugo and his hi-profile partner Pharrell Williams—and it’s in the middle of nowhere, nestled on the border between a yawn of a residential area and a strip of strip malls. The only things around are a self-storage warehouse and Williams’s colossal tour bus, so we pass the time by talking about what rap sucks (according to Malice: lots) and what rap doesn’t (according to Malice: Eightball & MJG). I briefly try to explain the plot of the videogame Halo without herbing myself out too much (you try talking about messianic super soldiers to a guy who claims to make city blocks look like The Dawn Of the Dead), but generally we’re in neutral.

The reason we’re trying to get into Hovercraft is to hear Hell Hath No Fury, Clipse’s long-awaited second album. I’d be fine hearing it on a car stereo, or at this point, a Fisher Price cassette deck, but Pusha insists on Hovercraft’s 26th-century speakers. He will not budge on this.

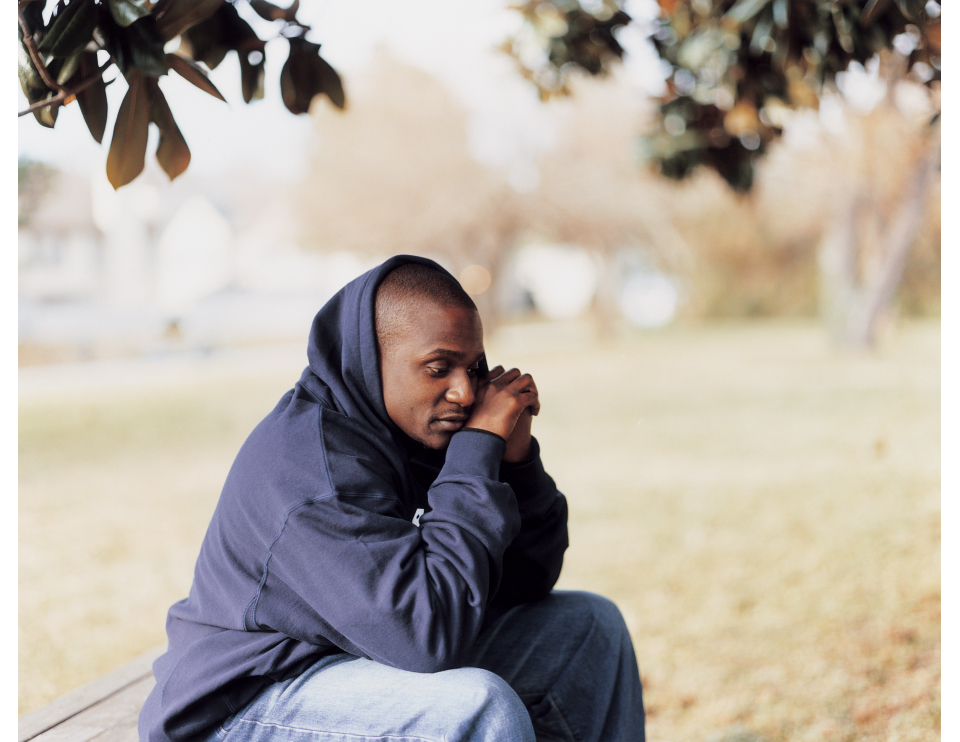

First we wait for Hugo. Then Hugo comes but he has the wrong key. Then Hugo comes back and realizes the key was locked inside the studio. Virginia Beach is pretty isolated, Norfolk being the closest “city,” and the winter there is one long, dull Sunday. When asked what there is to do amongst the empty crab shacks and boarded up beach attractions—if there are any hidden nightspots—Pusha replies, “I don’t really go to clubs. Unless it’s a dark, angry one. I pretty much just drive around and think of rhymes.” Then he looks at his SL coupe like it’s his home.

Pusha and Malice have been sitting on, tinkering with and tending to Hell Hath No Fury for over three years now, and whatever momentum they had coming off the success of their debut Lord Willin’ was halted by all the red tape that goes along with those fun mergers that make the music business such a special industry. In the case of Pusha and Malice, original label Arista merged with Jive. Then came the winter(s) of Clipse’s discontent.

“Hell Hath No Fury was a record we could’ve dropped soon after Lord Willin'. We had singles ready, but the merger smashed everything,” says Pusha. Clipse doesn’t really gripe about their label woes (their contractual release from Jive seemed imminent—maybe—at press time), beyond Pusha saying, “This was a situation that the Clipse didn’t put themselves in.” But the entire ordeal seems to have dug a giant chip on their shoulders—one that transcends disaffected rapper syndrome, approaching existentialism.

The cloud that followed Clipse and their album has had a deep impact on the music they’ve made. A version of Hell Hath leaked to the net about a year and a half ago, one with songs that were reminiscent of their club hit, “When The Last Time.” But as months went by and release dates became more and more comical, Clipse dragged their music into the same darkness they were feeling.

“There’s a model for an album now and we go against that,” says Pusha. “There’s a single, the club record, the girl record. But Hell Hath is just one big-ass street record. When we freshened it up we took away the moods we weren’t feeling anymore. So I can’t give you the girl record, because I’m mad. I ain’t got nothing to say about women. I would tell people that we were trashing some of the softer stuff on the album and they’d be like, ‘Yo! How can you lose that one!?’ Nah, I’m not feeling like that right now. It’s angry shit.”

“I don’t think we’re re-inventing the wheel. I could tell you gruesome stories; hangings, kidnappings, all types of wild shit. But I think somebody else can too!" — Pusha T

Clipse came onto the scene in 2002, accompanied by the once-in-a-lifetime drums of “Grindin”, and they seemed to be, in retrospect, a vehicle for the Neptunes most experimental music. They were minimal, terse and they stayed out of the way, rhyming about drugs, girls and cars with blank faced stares. But as Hell Hath sat in purgatory, the group decided to break their silence with two volumes of a mixtape called We Got It 4 Cheap, released as the Re-Up Gang, featuring Philly MCs Ab-Liva and Sandman. The revelation of the mixtapes, particularly Vol 2, is hearing a group once defined by their beats now define beats. Vol 2 is a mixtape that feels like an album. Eighteen tracks, all of them, more or less, about cocaine. If it sounds limited or repetitive in its subject matter, it probably is. But that’s also not a surprise—Pusha helped usher in a newly hyperbolic era in the long history of the “rapper as drug dealer” persona when he succinctly reversed those roles, declaring on Lord Willin, “I’m not you, rapper.”

On the first We Got It mix, Push rhymed, “I’m feeling smothered by this music industry/ I need a breather/ So guess who’s back selling that shake like seizure.” It is one of dozens of explicit references to “Pusha” not only being the rapper’s name, but also his occupation in the midst of his music biz hiatus, even with “Grindin” royalty checks certainly still making appearances in his mailbox. Over the course of two days in Virginia Beach, I asked him plenty of questions about dope dealing, so many that he probably thought I was moonlighting as a narc. It became apparent a) he wasn’t going to incriminate himself and b) the lyric was more symbolic then literal. It means he went back to the source, to the vocabulary, stories and imagery that informed his rhymes to begin with. “A lot of it is personal experience. Some of it is neighborhood legend,” says Pusha. Nobody doubts Pusha’s rep—at least not me—but it doesn’t really matter. He seems uninterested in going into his hood resume and cares little of other rapper’s credentials. “If you got shot, so what? That means a nigga didn’t duck,” he cracks.

When asked whether he thinks Nas did half of what he talks about on llmatic or It Was Written, and if that changes the value of the art, Push responds, “I don’t think Nas executed a housing cop, but that doesn’t mean ‘Shootouts’ ain’t mean as hell.” Then he elaborates, saying, “Everybody who does this kind of music, we’ve basically seen the same things. You have to remember that this is still an art form. I don’t think we’re re-inventing the wheel. I could tell you gruesome stories—hangings, kidnappings, all types of wild shit. But I think somebody else can too! And their shit might be crazier because they live in bigger cities. Anyone can do it, but the creativity is what matters.”

Elvis Costello once complimented Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker’s lyrics by pointing out his way with details—the “woodchip on the wall,” for instance, in Pulp’s single, “Common People.” This is exactly what makes Clipse special. Cocaine is just a powder that makes you feel good and then makes you feel bad. But in it, and in everything that surrounds it, Pusha and Malice have found limitless possibilities, thousands of ways of talking about one thing.

On Vol 2, Clipse’s rhymes, especially Pusha’s, somehow depict the world of cocaine dealing, nice threads and souped-up cars with as much playful, insightful, funny, sad, thought-provoking depth as any good poetry presents something pedestrian as something extraordinary. At the beginning of “Roll With The Winners”, the group’s take on TI’s “Get Your Shit Together”, Pusha ad-libs to himself, or his engineer, “Let it go.” What follows is a barrage of images, history lessons, boasts and regrets. My uncles before me mixed the diesel in the blenders/ Then crack came/ It was the coldest of winters…I come from a line of ex-kingpins turned sniffers/ Pray the lord forgive us while the mighty cones fill us/ Up to the brim/ Call ’em the coffee bean spillers. Kilos are called God’s pillows, and the drug takes on a mythic—and elsewhere, almost erotic—quality. He even flips the usual mea culpa that drug-rappers offer for their actions, replacing guilt with an almost Darwinian take on the addict-dealer relationship: I flew it in/ It ruined men/ I'm through with them.

“You could say those things a million different ways,” says Pusha. “A line like, ‘I’m from a line of ex-kingpins turned sniffers,’ a lot of people wanna talk about how their people or their family was getting it, selling a whole bunch of drugs. But, shit, from what I saw,” he pauses, looks down for a second, then says, “It turned out another way. You gotta keep the downside in there. Being young, I saw the glamorous side of it, but now, being older, I can tell you a lot of them did turn to sniffers. Nothing to show for it.”

In his own rhymes, Pusha doesn’t let himself off the hook—he holds himself to the same honest standard, and sometimes even goes one or two steps further. “A lot of guys wanna talk about how they got all the bad bitches,” he says. “But you have to say—if you’re gonna be true—you gotta say, ‘I fuck gold digger bitches,’ cause that’s what they are! And put yourself in there too!” He quotes himself again, rapping, “‘Fuck gold digger bitches/ My Giuseppe freaks/ Mama, I mean no harm, you lack class and charm/ But I ain’t got it either.’” Pusha then parses his own line, explaining, “I’m fucking you. Here we are. It’s the same shit, we’re in it together.”

"There’s a model for an album now and we go against that. Hell Hath is just one big-ass street record." — Pusha T

Despite the feast of rhymes on the mixes, Pusha seems nonplussed. “The mixtape is cool, but I think you’re gonna find Hell Hath more conceptual. If I went to a radio and tried to freestyle Hell Hath No Fury verses I’d have a hard time rapping. On the mixtape we’re trying to say the flyest shit. Hell Hath is that motherfucking lock you in, close the door, black out the windows, if you smoke, light that shit up.”

Which puts us back in the parking lot, many hours later, after a long day of driving around in a place where everything is “about 20 minutes away.” Hugo has finally located a set of keys and Hell Hath No Fury is finally about to get played. There’s nothing to smoke or drink around, although Chad does keep asking if I want a Crunk Juice (“Maybe he’s on the street team,” cracks Push.)

Over the course of the day, Pusha has become increasingly evangelical about the merits of Hell Hath No Fury. It goes beyond the Yo, cop my album, droppin Nevuary 23rd rhetoric and goes into near fanatical obsession. But then, with all that anticipation, there’s even more waiting as Hugo himself plugs in various computers and pieces of stereo equipment. Pusha is starting to get animated, standing in his socks to keep his BAPE’s immaculate, imploring me to listen to the rhymes, even though it’s my first go-round.

Then the music kicks in. And as the opening bars of “Ride Around Shining” begin to deplete my hearing, something happens. What was supposed to be a listening session becomes a performance of sorts. But really a celebration. Pusha is dancing, rhyming his and Malice’s parts, pantomiming the lyrics, pausing and rewinding to go back through his favorite punchlines.

“’Make all of her twist like Dickens!’ That shit is for the English majors, son!” he shouts over the music. It’s uncompromising. Relentlessly dark, with the Neptunes’ production—all sparse, fucked-up drum programming and droning keyboard runs—perfectly complimenting the lyrics of both MCs. Push plays his favorite cut, “Mama, I’m So Sorry,” twice in a row. The point of the song is actually that he’s not sorry at all. He doesn’t give a fuck. He’s angry. But right now, with Hell Hath No Fury finally playing and a smile on his face, with Hugo dancing, with his manager rapping along with him, Pusha is, for the moment, happy.