From the magazine: ISSUE 89, December 2013/January 2014

For about the millionth time, a car rockets off a cliff and lands in the water below, but no one really says anything about it. Travi$ Scott, a lanky, 21-year-old rapper and producer from Houston, is renting a room at New York’s Hudson Hotel with a bunch of childhood friends, many of whom now live in the city but currently seem to be enjoying a stay-cation, sitting on the couch, smoking an endless stream of blunts in between cautious swigs from a bottle of Jameson. The crew is laconically, borderline disinterestedly playing Grand Theft Auto V. Scott beat the game a few times already, but there’s something wrong with it and it won’t save, so they’re just messing around, playing through the early parts, exploring the game’s eerie topographical accuracy before launching cars off precipices and into buildings at random, then tossing the controller to the next person on the small couch.

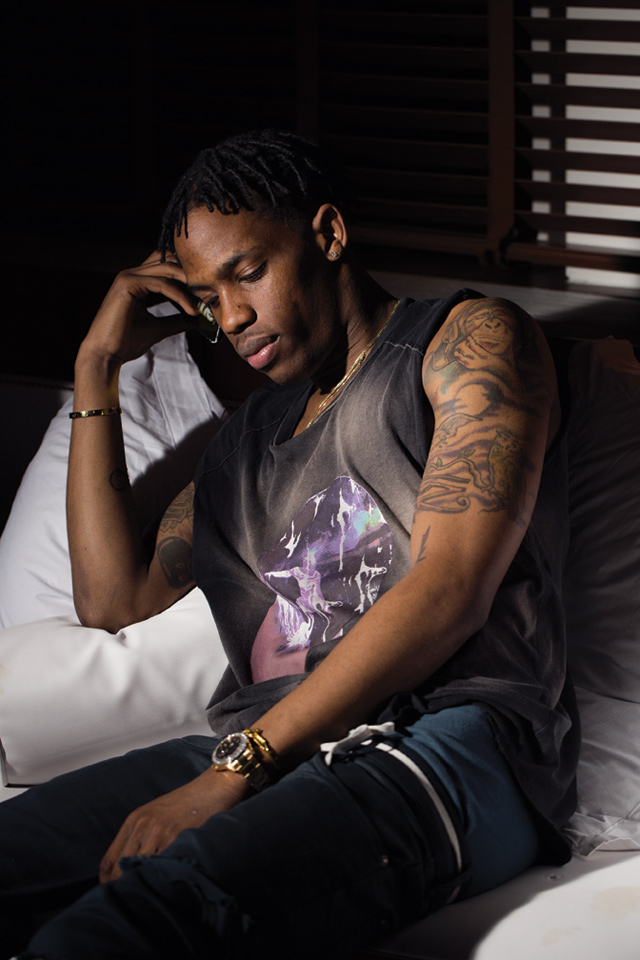

The light is dim but warm and Scott is in the other corner of the room, hunched in an office chair, staring into the glow of a laptop and twiddling his stubby braids, which caterpillar off his head and stop short of his temples. It’s a chaotic space, but he’s so zoned out that he barely notices his friends’ endless run of suicide missions.

Instead, he’s trying to find the right drum sound for his remix of King Krule’s dubby “Neptune Estate.” The pairing, initially, seems a bit weird. King Krule is the recording alias of Archy Marshall, a 19-year-old British singer/songwriter with an old soul and a voice that sounds like it’s been dragged through cigarette ashes and a couple sludgy pints of beer. Scott, for his part, makes music that plays out like the soundtrack to a bunch of Transformers fighting each other in a post-apocalyptic desert landscape, with towering synths jockeying for position against drums that sound big enough to eat the whole world. Still, both artists thrive in a musical environment that allows them to seem like the only people left on earth; it’s like they’re linked by a bombastic caricature of loneliness, Scott with his wide-open expanses and Marshall with his drizzly London streets.

Right now, Scott’s zeroed in on a drum loop that sounds like it’s submerged in cotton and a couple snatches of a verse, which he’s mumbling into the microphone, barely saying words, grasping at a cadence and flow that’ll match the vibe of King Krule’s original. As Scott gets more confident, his voice gets louder, his words clarify and his subtle Houston drawl gets more pronounced. His friends, who haven’t really been paying attention to what he’s doing, get quiet, or at least quieter. When Scott gets stumped about which words come next, he asks, “Did I write this on somebody else’s phone?” Phones are passed around, and eventually, he finds it. The “writing” is actually a voice recording from sometime earlier. He listens to the blown-out fragment a couple times, then hunches over the mic like he’s focusing on a school test: Stumbled out my hotel late…voice receding to a mumble again…knocking on my mama’s door, she couldn’t tell I wasn’t sober. He’s speaking even lower now, but it’s clear that he’s found what he was looking for. He stops, proudly letting out a “WHOOOOO.” All of this seems to happen in a matter of minutes, which suggests that Scott is both sure of himself and the kind of artist who is always turning ideas over in his head, thinking about the music he’s going to make even when he’s not making it.

Recently, Scott’s been on a roll. In 2012, he spent time in Hawaii and New York, working on the Kanye West-helmed G.O.O.D. Music posse album, Cruel Summer; 2013 brought him to Paris, once again working with West on the now-notorious, whirlwind Yeezus sessions. His conversations are peppered with anecdotes about meetings with major record executives, and he’s brimming with stories about hanging out with West. He’s excitedly told multiple interviewers one that involves West getting a Taco Bell Doritos Loco taco delivered to his studio on a Hermes plate.

Before that, Scott spent a large part of his early adult life shunting around the country in search of his own career, taking label meetings that went nowhere and were often canceled or pushed back even as he was flying to them. Today, he seems poised on the brink of success, securing, with the help of his manager Anthony Kilhoffer (a producer and engineer who has known West since 2002, and worked closely with him since 2004’s College Dropout), a spot at three tables in the hip-hop powerhouse—a deal with Epic, plus affiliations with West’s G.O.O.D. Music crew and T.I.’s Warner imprint Grand Hustle. But it took a move from Houston to New York, then Houston again, then New York again, and now, for the time being, Los Angeles, to get there. “I just like the vibe,” he says of LA, like he’s thinking about it for the first time. He’ll later recite the whole list of back-and-forth moves wearily, virtually counting off locations on his fingers as though each held thousands of miniature success stories and close calls with personal failure.

Listening to Scott talk about his early days as an artist, it’s clear that his talent was there, but his direction was not. In high school, he rapped over other rappers’ instrumentals but that didn’t feel quite right, so he started making his own beats. “I used to call myself a producer, but I was an engineer,” he says. “I used to record my friends, and I thought that was being a producer. Then I saw that ’Ye video where he had the yellow Polo [and was producing tracks] and I figured out…Damn, that’s what that is? I gotta make beats.”

“My vision was being ahead of what’s going on—like two, three years ahead.”

Scott’s childhood home in Houston, where his mother worked at AT&T as an Apple liason and his dad ran his own advertising business, soon became a revolving door for friends and randoms from school who wanted to record. “I was always in a group,” he says, speaking of his early projects. “I feel like my shit was tainted because either somebody’s voice wasn’t right or I was sounding corny as fuck,” he says. “I was in a group with another rapper. This nigga was like my best friend. I had a vision and he had a reality. Those are two different things. My vision was being ahead of what’s going on—like two, three years ahead. He was living in the reality, hanging out with niggas he would think was his friend. It was the downfall of everything. You gotta learn how to completely not fuck with people. That’s a hard thing to do. Just keep walking. Trusting your own vision.” Some of those projects, including TravisxJason, a duo he was part of with a rapper named O.G. Chess until they had a falling out in 2011, can still be found with some creative googling. Their full-length, Cruis’n USA, is promising, largely inoffensive and miles away from the darker terrain Scott would soon inhabit with Owl Pharaoh, his biggest artistic statement to date.

That mixtape, released last spring, is a joyfully dark collection of maximalist, wheezing tracks that lumber under their own weight, gears grinding to push out laconic future music hatched from Houston’s long lineage of screwed-down songs that evoke codeine and candy paint and drowsy psychedelia, but imbued with Texas’ lonely flatland and Scott’s husky, often deadpan voice. Scott’s been on a Robert Rodriguez kick lately. At one point, mid-sentence, he pauses to look at the TV, where a trailer for the director’s Machete Kills comes on. Scott points at the screen. “That’s why I gotta work with this guy,” he says, as the actor Danny Trejo, stone-faced, stalks across a burnt yellow desert landscape in slow motion.

Scott’s sound is ambitious, but it isn’t exactly experimental. Instead, he’s working in the anything-goes mold already supplied by numerous artists before him: West’s towering artistic statements, T.I.’s elastic voice, the Neptunes’ digital experimentation. Like any kid that grew up in the internet era, Scott has absorbed everything around him, blended it together and come out with a style that is a product of all music everywhere existing on the same plane. Nothing is off-limits when you have access to everything. And with that access, Scott is dead-set on mastering every art form he takes on. “I was always about doing both,” he says of rapping and producing. “I wanted to learn. I wanted to know how to do it. That was my biggest thing about everything. I wanted to know how to use everything. That’s why I do videos. I know how to work a camera, edit a video. I just want to know. I don’t like someone knowing more than me.” His music is an appropriately cinematic reflection of his open mind and keen ear, blending iconic phrases from other people’s radio hits with a production style that evokes every regional rap trope, from New York’s claustrophobically heavy drums to LA’s slow-rolling funk, without sounding like much of an imitation of any of them.

The first time you hear his voice on “Uptown,” a highlight from Owl Pharaoh, he sounds pretty much like how you’d imagine the devil to sound. Over grating, hyper-compressed strings, his multi-layered voice grunts, I’m riding up uptown/ WHOO! I’m a motherfucking monster/ WHOO! One hand on the wheel one hand on my dick. Then his words start speeding up, finally colliding into each other in a manic fit: At the green light I’m speeding/ Fourth wheel on, I’m weaving/ I got red eyes...swag seizures. The motherfucking monster line is a callback to West’s “Monster,” but here Scott sounds like he’s living up to the impossible claim. He sounds inhuman.

Even in his day-to-day life, Scott has the energy of a hyperactive teenager. He works constantly—often in hotel rooms or random studios scattered all over the world—but he’s rarely alone, and, if he’s not making music, he’s always in motion. He climbs on things, wrestles his friends, knocks over lukewarm water into a pile of Swisher shards, tosses his shoes into corners and then kicks them into other corners. He wanders New York with the familiarity and complicated emotions of a former resident. At one point, he scores a pair of green BAPE sandals that are basically modified Birkenstocks, and he wears them everywhere the very next day. Later, at the boutique clothing store Surface to Air, he tries on a sweatshirt, but his friends deem it too small, so he sits down on a bench, hits his G-Pen and puts one of them in a headlock.

“Travi$ is not here to make number one rap songs. Those people get high off of making number one songs. I’m into making number one fucking albums.”

It’s this surplus of nervous energy that makes Scott such a compelling performer. Live, he makes every stage seem like it’s actually a trampoline. He is never not jumping, flailing, pacing, climbing rafters, screaming his voice raw. There’s a video of a performance at New York’s club S.O.B.’s last summer where, just over three minutes into his set, he already has his shirt off, the room is pitch black, the crowd is chanting along with him and it looks more like a hardcore show than a typically discerning, not-impressed-by-anything, dead-eyed New York rap crowd. In interviews, though, Scott is all over the place, half-finishing thoughts, going on hilarious tangents that take him miles from his original point. But his enthusiasm skews these moments as charming, not embarrassing. When he talks about his long-delayed first meeting with West at the Jungle City recording studios in Manhattan in 2012, while working on Cruel Summer, his story is a mess of clipped sentences that dead-end even as they get more enthusiastic:

“[Anthony] Kilhoffer, my manager, has known ’Ye for X amount…I didn’t even see ’Ye for like four weeks. I was like, What the fuck? This is kind of weird. I was in some studio around the corner. I added shit in on ‘Theraflu’ and that was it, and that was when I met Lifted for the first time—that was the dude that did the ‘Mercy’ beat. I got hit up like, Yo, we want you to fuck with this ‘Mercy’ track. I fucked with it and turned it in. It came out and I was like, Oh shit! That’s the first time I heard some of my sounds. So time goes on and I didn’t meet ’Ye yet, and I was like, Man, that’s weird. So I get back to Jungle City and they’re like, Yeah, he wants to meet you around five. And I didn’t see this nigga for three days. I did the ‘Don’t Like’ remix—the drums and shit. [Young] Chop lost the files for the track, so man…Then I met him. I played him what Owl Pharaoh was at the time and he was like, Whoa, and I was like, I got these ideas, and I was singing on it, and we just kept talking…”

Scott is clearly working in the shadow of West, not only in the tone and cadence of his rapping, but also in his disinterest in participating in a traditional path to fame. Success for Scott doesn’t mean being the most visible, or making the most hits. It means having a clear vision of what he wants to do. “I feel like I’m the opposite of the system—I’m the opposite of what Mike WiLL is,” he says. “You will not be able to compare me to a Mike WiLL or to a Young Chop or any of these niggas that make number one rap songs. Travi$ is not here to make number one rap songs. Those people get high off of making number one songs. I’m into making number one fucking albums. Extended long projects that are consistent. That system is the A&R calls you, like, Oh I need a beat for this nigga’s album, for so-and-so’s album, like a Mariah Carey.”

Scott’s belief in the emotional power of the album format isn’t just willful ignorance of the music industry he’s part of, though. He saw a disconnect between what labels wanted and what he was looking for, and decided to follow his own instincts so that he wouldn’t be manipulated by an out-of-touch industry. “Niggas was going mad platinum because they couldn’t download music for free,” he says. “That’s what labels gotta realize. It wasn’t just because you was the best motherfucker alive, because y’all the best label. It’s just because niggas couldn’t access the internet fast enough. Now niggas is smarter than you. It’s like the fat white man sitting in the chair, like, Ah, yes, we got these motherfuckers, they can’t get this shit for free. This is the only way you can buy it. You cannot be commercial no more. You must be real.”

Apparently, realness is synonymous with fearlessness for Scott, because during the numerous photo shoots he participates in for this story, he inexplicably finds himself in insanely high places. At one point, he’s crouched precariously on the corner of the roof of a photography studio in the Flatiron District, a coat hanging from his body like a high-fashion version of Batman’s cape. His face is partially obscured by the fabric, Phantom of the Opera-style, but his grill—which he is currently stretching his mouth wide to show off—is glinting in the remnants of the evening sun.

Not 24 hours later, he’s on the top floor of a very tall construction site. The building is still unfinished, so everyone is wearing hard hats and ugly neon vests. The floor is littered with construction equipment and massive metal girders. Scott’s surrounded by exposed concrete foundation that’ll eventually be covered up. Right now though, people are taking pleasure in writing their names and the date all over the wall, anxious to be an invisible part of the city’s history. Scott wants to do this too, so, Sharpie in hand, he scoots himself up some wiggly plywood that’s angled against the wall and writes his name in blocky letters on the grey surface, shading in parts of the T after he’s done writing it all out as big as he possibly can. The marker is thin, so it’s not really visible unless you get up close, but he works meticulously anyway. A couple times Scott slips back down the plywood, but he wedges his feet, grips the pen and gets back to work. Pretty soon, all this will be covered. Probably no one except some construction workers will see his name here, but he’s leaving his mark anyway, exactly how he wants it.