Fourteen of Trent Reznor's colleagues retrace his path from college freshman to music industry icon

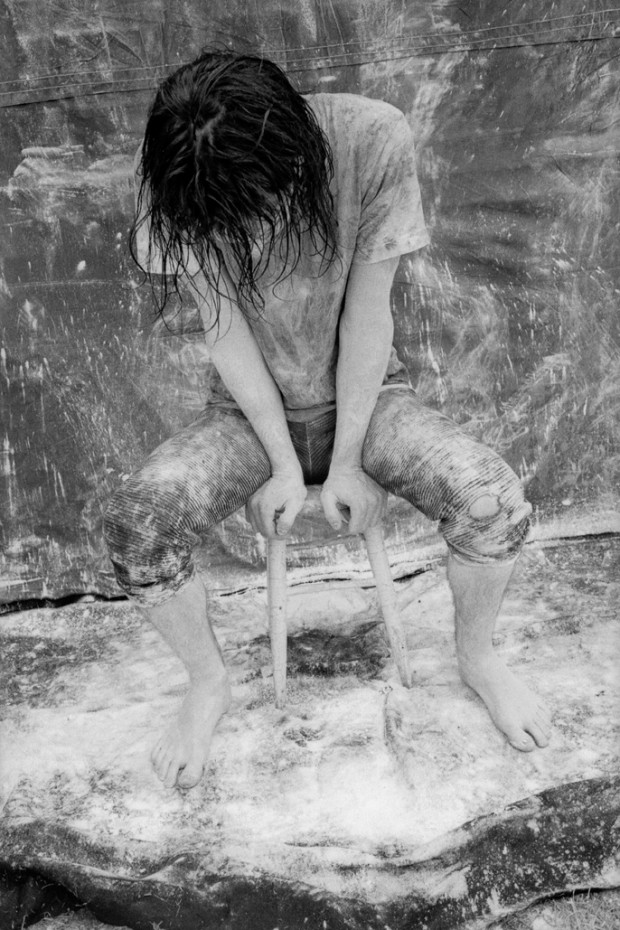

Above: From left, Trent Reznor, Richard Patrick and Chris Vrenna in South Bend, IN, 1989. Photography by Jeffrey Silverthorne.

From the magazine: ISSUE 88, October/November 2013

Trent Reznor owes his success in the past quarter century as much to his music as to his meticulously maintained image: the strong-headed iconoclast intent on doing it his way. But behind the prickly interviews and somber façade lies a far more nuanced individual. By talking with many of Reznor’s friends and collaborators from over the years, we thought we’d retell his story through the eyes of the people closest to him. What emerges is an artist who crafts some of his era’s rawest albums while maintaining a cool aura of inscrutability, a dogged musician with limitless stores of energy and an icon who has never stopped evolving.

ANDREA MULRAIN

Former Atlantic Records A&R, college girlfriend

Trent stood out from the crowd. Allegheny College was very conservative and preppy. There was no hipster/indie scene at all. He was pretty much the only person who had a distinctive style. He was like a mod or a new-waver. He used to wear parachute pants, and this was back in the ’80s, that whole MTV era. He looked like he had just stepped out of a video.

I approached him one night. We were queueing up for dinner, and I said, “Hi, are you from New York?” And he said, “No, I’m from Mercer, but thanks for the compliment.” That was the beginning of our friendship. Within a day or two, I noticed a flyer for his band, Option 30. They were playing downtown. I gathered a bunch of my girlfriends, we went down to see the band, and I was just instantly blown away. He was so charismatic, and he put on such a great show—it was obvious to me that this kid had a lot of talent. The next day was my birthday, and he showed up at my dorm room with a bunch of Twinkies with candles in them and sang “Happy Birthday,” which I thought was very endearing. It’s hard to imagine Trent Reznor doing something like that, but when I knew him he had a very playful personality. He was a big practical joker.

Within a few months, he realized that he wasn’t really connecting and integrating well into collegiate life. For somebody that young—he was only 18—he had a lot going on. He was constantly practicing, tinkering with his electronics—he had one of the first Memorymoogs in America. He was throwing himself into his music to the exclusion of his studies. In the end, he couldn’t keep up with both. Gradually, he extricated himself from campus. While he was gone the following year, he sent me flowers on Valentine’s Day. He dropped in unannounced once, and I’ll never forget this: he had his dad’s sports car and he surprised me, picked me up and whisked me away. We went out on this wild ride with the top down. It was something out of a Tom Cruise movie.

—

Having dropped out after his freshman year of college, Reznor relocated to Cleveland to pursue a music career.

BART KOSTER

Former owner of Cleveland’s now-defunct Right Track Studios

I was building a studio and brought Trent on before I even moved into the building. He was working at a place I used to frequent called Pi Keyboards and Audio, selling equipment. Trent was articulate; he was funny. We were both big fans of David Lynch. Trent had a lot of skills as far as working with equipment and keyboards, which is why I thought it would be a pretty painless transition to engineering. He picked up on it right away. As a matter of fact, he was teaching a recording engineering class after not too long. Every now and then, I run into somebody and they go, “You know, Trent recorded my first record.” Trent’s first gold record wasn’t even his own—it was a recording he did of a group called Troop.

I said, “Hi, are you from New York?” And he said, “No, I’m from Mercer, but thanks for the compliment.”—Andrea Mulrain

Reznor in South Bend, IN, 1989.

One day, he gave me a cassette with about four songs on it that he had been recording on a Tascam four-track. I remember “Down In It,” specifically, grabbed my attention. He asked me to give it a listen and if I’d allow him to record after-hours. I was just impressed with his creativity. I thought they were good tunes. I couldn’t see any point in arbitrarily denying him, so I said, “Yeah, go ahead.” And he took full advantage of that. He’d work all day long, and then stay up all night working on his stuff.

RICHARD PATRICK

NIN guitarist from 1989-1993, lead singer of Filter

I’d heard he got a record contract. I couldn’t believe it. Someone completely broke out, left shitty Cleveland and got a record contract. Nine Inch Nails had already played a few shows opening up for Skinny Puppy and Trent said, “Why don’t you come and hang out?” I got into his car and he played the Adrian Sherwood “Down In It” mix. It was just massive. I was like, “Are you rapping?” He was like, “Kind of.” Then he played me “Head Like a Hole,” and I went, “Dude, that’s a fucking huge hit. I’m in if you want me to go on tour.” And he was like, “All right, well, we’re gonna get a van.”

"He played me “Head Like a Hole,” and I went, “Dude, that’s a fucking huge hit. I’m in if you want me to go on tour.” And he was like, “All right, well, we’re gonna get a van.”—Richard Patrick

ANDREA MULRAIN

When he sent me the first NIN demo I was working at Atlantic Records—this was late 1988—and he and I had stayed in touch a little bit. There was a letter explaining that he had been pitching it to different labels, and much to his surprise, he’d gotten overwhelmingly positive responses. I was impressed with the production quality and the caliber of the songwriting. I was a little bit surprised by the musical direction he’d chosen, because it was a lot more aggressive, edgier than anything he’d done before. But to me, it was unquestionable that he would be successful. I remember my boss said to me, “Could you please see if you can get your old boyfriend in here for a meeting?” By the time we got to the party, he had already signed with TVT. When we were doing CMJ—this was probably ’89—they were setting up Pretty Hate Machine. I remember going to the China Club in Manhattan to see him perform. There was this palpable level of excitement and anticipation about that release.

RICHARD PATRICK

Trent said, “Don’t get bored. Play it like you fuckin mean it, like, ‘Fuck you!’ Everything is about intensity. You have to completely dedicate yourself.” So I just went off as hard as I could whenever I played anything. On tour, it was just about creating as much chaos as possible.

—

Following the success of Pretty Hate Machine, NIN was invited to play Lollapalooza in the Summer of 1991.

ALAN MOULDER

NIN producer since The Downward Spiral

I was working with Jesus and Mary Chain, and we went to Lollapalooza to see NIN. Someone introduced us, and Trent said, “Do you know this other producer? Is he a friend of yours?” I said no, and Trent just started railing against him. “That guy, he’s such a…” At that point, I knew we’d get on.

RICHARD PATRICK

We were a drinking team: “I’m nervous. You nervous? Let’s have a beer.” You’re 22 and you’re at Lollapalooza, hanging out. We were obnoxious, although Trent would always try and make sure that he maintained a certain amount of clarity. One time someone gave us a press packet with a demo, and Trent and I just basically destroyed it right in front of the guy. We broke the tape in half and wrapped ourselves in it.

NIN performs at 1991’s Lollapalooza in Irvine, CA. Photography by Neal Preston.

After Lollapalooza, he was setting up his future, and it was pretty obvious it didn’t include me. I’m like, “You’re going down to New Orleans and renting this cool house and you got a record contract. I’m gonna go home to my mom and dad’s basement.” He says, “Dude, write a fucking record.” I looked at him like, What a dick. But it was time for me to figure out what I was going to do with the rest of my life. Trent could’ve found better guitar players, and he did.

BART KOSTER

We met up after one of his Cleveland shows. Courtney Love opened. At the party afterwards, she was passed out on a pool table. I ran into Trent and we talked briefly about what it was like now that he had taken off. He was overwhelmed early on by his newfound fame. People treated him more as an object. He was complaining about how he couldn’t have real conversations with people. All they wanted to know was, like, his favorite color. He was just a little shell-shocked.

RUSSELL MILLS

Visual artist who created covers for albums including The Downward Spiral and Hesitation Marks

I was living in this 17th century house with views over lakes and a river running by. I was outside one morning, having a cup of coffee, looking at the shepherds, and the phone rings. It was Trent, Gary Talpas, his designer at the time, and his manager. They wanted me to do some work, and we came off the phone having agreed on everything. A couple days later, I had another call from his manager, saying that, actually, “Trent doesn’t work with anyone he has never met. You have to go to Manchester Airport on Thursday, there is a ticket there for you, and you have to come to Los Angeles on this particular day. You’ll have dinner with Trent and talk about the project, and then you’ll go home the next day.” When you meet someone sort of famous, you always imagine them to be taller. He was about the same size as me, but a lot stockier—very sort of American physique.

Reznor and Ministry bassist Paul Barker, backstage at a Ministry show, 1996. Photography by Paul Elledge.

ROBIN FINCK

On-and-off NIN guitarist since 1994

Trent was finishing The Downward Spiral and a representative of NIN made a very small handful of phone calls that they were looking for a guitar player for their upcoming tour. They called somebody in Atlanta, who was the club owner of The Masquerade, where I was kind of holed up. He called me up to his office. I had just received my letter of acceptance to Berklee College of Music in Boston and I told him, “I’m really not sure NIN is for me. Isn’t that a lot of black hair and synthesizers?”

I recall the production rehearsal for the Self Destruct tour [1994-96]. We’d been rehearsing for weeks in a band room, and now we were in the production rehearsals. In this rehearsal, unbeknownst to anyone, Trent went absolutely bananas: throwing water, throwing pedal boards, microphones flying in every other direction. Rather than tell people what to expect from the shows, he just broke everything until we couldn’t play anymore. I don’t think he was mad at anybody, but it really shook me to the core. The next rehearsal, everything was covered in plastic.

RUSSELL MILLS

For The Downward Spiral, we came up with some trigger words, like “attrition” and “decay.” So there were lots of rips and tears, exposing layers underneath. A lot of the thinking came out of classical ideas and stories. One was a story about a Japanese feudal lord who’d had an affair with one of his serving girls and then ditched her when he got tired of her. She took her revenge by serving him a meal, which looked beautiful, but as soon as he got beyond the top layer, it was full of dead bees. It was horrendous. Another was about a Roman emperor who was known for being lavish, and he had a party with hundreds of guests. At some point in the festivities, a big net was released, which allowed all these rose petals to fall from the ceiling, as a spectacle and to bring this lovely smell to the environment.

It ended up suffocating people to death.

ALAN MOULDER

I was surprised that The Downward Spiral sold so many copies. It’s a challenging listen. For that to sell four million albums is pretty impressive, you know? It was more eerie, and a bit more warped, than you’d expect from general popular music. It wasn’t just guitars, bass and drums. And if there were guitar, bass and drums, they’d gone through a mill of processing, to make it feel slightly wrong.

LEROY BENNETT

NIN lighting designer since 1994

It was violent onstage during those days. You didn’t want to get anywhere near it. One show, Trent threw his mic stand over behind his head and it hit the drummer, Chris Vrenna, and split his head right open. He was just bleeding nonstop and kept playing. I saw [Reznor] wrap his mic cord around Robin Finck’s legs and pull it out from underneath him, and Robin flipped over into the audience and kept playing. Didn’t miss a beat. He’d go through Les Pauls like water. I remember there was a time when his guitar tech, Billy [Howerdel], who is in A Perfect Circle now, was taking a guitar out of the box—brand new guitar, tuning it up, and just about to hang it up—and Trent smacked the head on it and just bent it right over. The head was at a right angle. That was it—done with that one. Every once in a while, he would take a mic stand and just whack a light from the top of a pylon on stage. Just smash it up—it’s $5,000. Just part of the show.

ROBIN FINCK

Nothing could have prepared us for Woodstock [1994]. That was the first enormous outdoor show we’d done. There were live feed cameras on the wings and a track of cameras in front of us, and in front of them, an aisle wide enough for an ambulance. I could barely see the face of the first person at the front of the barricade, they were so far away. However, the energy coming back from that body of humans was undeniably on the side of these songs. There was quite a connection made that evening. We came off the stage going, “Fuck, that was weird.” I don’t know that any of us knew how that would catapult the trajectory, the name of the band, and how many more people would be listening. It was powerful. I look back on it now and I see that it was the right time for us. I think the audience really drank the whole thing in. We didn’t really feel like we fit in, but when we took the stage we realized, Huh, we showed up and all these motherfuckers, they showed up as well.

Reznor filming the video for “Only,” off With Teeth, with David Fincher, 2005. Photography by Rob Sheridan.

ROB SHERIDAN

NIN creative director since 1999

I taught myself how to make HTML and bad graphic design by making a website about NIN. I was a teenager; I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. At the time, Trent did not have an official online NIN presence, but he’d been paying attention. NIN has always had an active fan community, one of the biggest ones on the internet. There are traces of Trent communicating with fans on message boards as far back as ’93. So he wanted to make an official site for the band, at a time when bands and corporations were only just starting to experiment with having official websites. He hired a web development team in New York but also wanted someone who was younger—a fan—as the link between him and what was going on in the New Orleans studio and the fan community. He brought me in for a meeting, and we ended up getting along really well.

Trent recognized early on that the most valuable asset artists have is access, and the importance of deciding how much of that access he wanted to dole out. At the time, there was a tremendous layer of mystique; the only glimpse you got of your favorite musician was in interviews in magazines or on MTV, so the internet was a new territory where fans could explore and peek behind the curtains. The stuff we did very early on with NIN.com was just toying with people’s anticipation by trickling out little details in the most abstract ways possible. You don’t see that type of website anymore because people don’t have the patience for it.

ALAN MOULDER

On The Fragile, we waited for lyrics for a long time because it was a place he didn’t want to go. There seemed to be a reticence. We had loads of music on that record, but hardly any of the songs had singing on them. That’s why there are quite a few instrumental tracks. The lyrics all came last. I think it was that he built it up, had to go somewhere uncomfortable, or the fact that he wondered if he had anything to say.

“We’re In This Together” was the last song we finished on the album, and one of the hardest songs to do. From basically a loop of a noise, it grew and grew into this big song. Piecing everything together seemed to take forever. We spent three weeks mixing and finishing it, and I think it was because it was the end of the album. We were all so tired, but I think we kind of almost didn’t want it to end. It’d been two years and we kind of dragged it out. He’s never played that song live. I think there’s a little bit of post-traumatic stress about that track.

ROBIN FINCK

The Fragility tour was a little more than a year, the beginnings of which were promising, and the end of which was a repeat of the same car crash we’d all experienced before. There came a time when there was no active, functioning NIN. It became a bunch of people scratching their heads at what was next.

—

After 2000’s Fragility tour, NIN went on hiatus until the release of 2005’s With Teeth. During that time, Reznor completed rehab for drug and alcohol addiction.

ATTICUS ROSS

Producer and composer

When I first met Trent, he was very recently clean. I’m clean as well, so I know how tricky that first bit can be. NIN hadn’t released a record for five years at that point. I remember him saying, “I don’t know if when I come back I’m going to be in clubs or theaters or arenas.” Rebirth is too melodramatic a word, but there was a big change in his lifestyle at the time. It’s easy to not feel as confident, or as settled, with those transitions being extremely difficult. It sucks. I would say that now he’s a bit more of a happy and settled person. I don’t think everything’s quite as in flux as it might have seemed 10 years ago.

ALESSANDRO CORTINI

NIN and How to destroy angels_ musician since 2004

I saw that NIN was looking for a keyboard and guitar player and I applied for both. I was never schooled on keyboards, but I’ve always been into synthesizers. When I joined, I’d see Trent at rehearsals, but after he’d disappear fairly quickly. He’s always been dealing with a side of NIN which we don’t really deal with, everything that has to do with the machine and not [the] music. We don’t deal with it because it’s not our business, and because if we did, we’d destroy it.

"Rebirth is too melodramatic a word, but there was a big change in his lifestyle at the time."—Atticus Ross

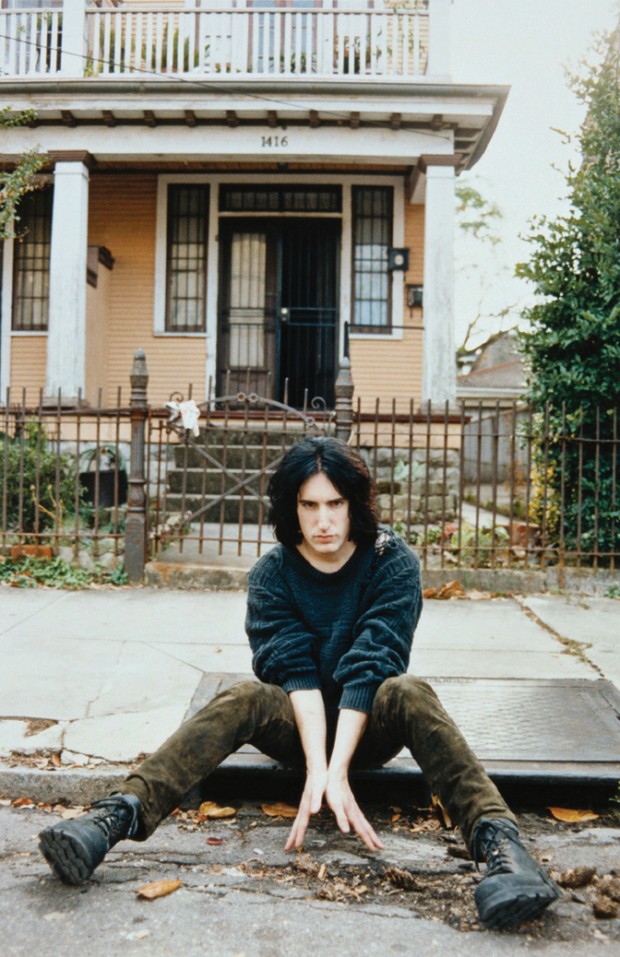

Reznor in the wake of The Downward Spiral, 1996. Photography by Kate Garner.

AMANDA PALMER

Former singer of Dresden Dolls, who opened for NIN on 2005’s Live:

With Teeth tour Trent was deliberately underplaying because this was his first tour back, and his first tour sober. I think he didn’t want to just explode out into arenas. The tickets sold out in about three minutes. There weren’t any casual fans there. Trent was very separate on that tour. He was the picture of military discipline. Everything was run like total clockwork. Everyone involved had an immense amount of respect for him, especially the crew. They were like a black-clad bunch of industrial freemasons. Trent was notorious for firing people if they didn’t do their jobs correctly. I remember joking to one of the techs about how incredibly serious everyone seemed to be taking their jobs, and I remember this guitar tech looking at me, straight in the face, and saying, “Don’t bring your b-game to Trent, man.”

SAUL WILLIAMS

Poet and singer who opened for NIN on 2005’s Live: With Teeth tour. Reznor produced Williams’ 2007 album, The Inevitable Rise and Liberation of NiggyTardust!

I connected with Trent at a moment when he was really looking to feel fresh. I got to know the clean, sober, productive Trent. He wanted to live. He had a gym backstage. He’d work out every day and play video games. He called my booking agent and manager and asked if I could tour with him because he had heard “List of Demands." Coming out of the hip-hop world, when I first put on a NIN album, I didn’t get it. I heard the drum machines, but everything was on beat. I’m like, “Yo, where’s the funk?” He played me Talking Heads’ Remain in Light and I played him Fela Kuti. Trent had never heard Fela before. We were both really into the same sorts of things, but from different angles. Every night of the tour, I’d look off the stage and see him on the side dancing during my set. After the tour he said, “I’d love to collaborate.” He was like, “The only way we can record together is if we book another tour, and I’ll bring an extra truck along with recording equipment and we can record in hotels every day.” And that’s what we did. That’s how we recorded NiggyTardust.

Reznor filming the video for “Came Back Haunted,” off Hesitation Marks, with David Lynch, 2013. Photography by Rob Sheridan.

ROB SHERIDAN

People see Trent do something bold, like break away from a label and put an album out for free [The Slip, 2008], and they react as if he’s creating a new business model that’s going to work for everybody. The mistake there is that Trent’s not trying to solve this problem for everyone, he’s just learning from experimenting.

ALAN MOULDER

For “Pilgrimage” [from The Fragile], he said, “I hear a marching band playing the melody, coming in, but from down the street and going past.” He spent two days creating a marching band, because we weren’t gonna get one. Then you put it through all this processing so it sounds like it came from a 1930s record. It actually started off sounding amazing and massive, and then you make it sound absolutely minute. It’s neverending. You never know what’s coming. He still says to me today, I think there’s a bit more going to go on this—don’t worry, it’s not going to be a marching band. There’s no limitation to his imagination. If he has an idea, he will never dismiss it because it’s going to be too much hard work. Trent works incredibly hard at being vital. That man works seven days a week. He’s never switched off. He doesn’t do holidays.

ROBIN FINCK

He’s always really been driven to give attention to the minutiae of the presentation of the songs. What’s different now is that dressing rooms stay intact and people are probably up earlier in the morning. The personality that exists now in relation to who he was—who we were back then—is very different. But the songs are the portal tying those two together.

ALESSANDRO CORTINI

On tour from 2004 to 2008, onstage I only had controllers. The computer brain that was making the sounds was offstage. There weren’t that many variations that could be discovered on a nightly basis. What pushed me away from the band when I left in 2008 was that it was becoming automatic, basically the same thing every night. I didn’t feel that I was giving it my best, so I didn’t feel right being there. I left before the tour was over. NIN continued as a four-piece for 2009, then took a break. I kind of knew that [the hiatus] was coming. Trent had been touring longer than I had. I knew he was getting tired and ready for something else.

—

In 2009, Reznor again put NIN on pause. Between then and the release of Hesitation Marks, Reznor produced award-winning scores for The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Along with his wife, Mariqueen Maandig Reznor—who declined to be interviewed—Rob Sheridan and Atticus Ross, he also launched the musical project how to destroy angels_.

ATTICUS ROSS

We spend an awful lot of time together. Ninety-five percent of the time [leading up to a release] was us in the studio. We do a lot of recording. It may start with something Trent’s played on a synth or a sound that he likes. Then we build and build on top of that. We’ll loop something, start recording, and over that Trent can perform for—sometimes it will be going for an hour. He’s just lost in playing. There is no bad note, no mistake—none of that matters at all. Within the junk of what’s recorded, we’ll be able to find the thing that feels best. It’s kind of like a sculpture, something coming together. And at some point, something magical happens.

RUSSELL MILLS

Just before Christmas 2012, I got an email from Trent out of the blue, saying that he thought there was another album. Trent had been thinking about the idea of specimens, the kind you see in natural history museums—this whole thing of taxonomy, systems and trying to organize and understand genres or behavioral patterns. I used a phrase in a conversation with him: “The black box in the wreckage.” He said, “What the fuck do you mean by that?” I said, “You have an air crash, and you have this black box which is a data recorder, and it documents all the factual evidence: cold, analytical, scientific information. And yet you still have this wreckage, which you can’t get your head around. Beyond that physical wreckage, there’s another layer of damage, which is damage caused to people who are related to, or love, the people who were affected by this plane crash.” I was talking about this as a kind of analogy for what he’d been through, for what I’d been through and also, hopefully, on a more universal level.

“It seemed to me that our methods were very much the same—approaching the writing process through color, working the textural and tonal relationships of the track, much in the way an abstract painter works.”—LINDSEY BUCKINGHAM

LINDSEY BUCKINGHAM

Guitarist and collaborator on Hesitation Marks

When Trent sought me out to play guitar [for Hesitation Marks], I was quite pleased. Even though our styles differ, it seemed to me that our methods were very much the same—approaching the writing process through color, working the textural and tonal relationships of the track, much in the way an abstract painter works. There was really no verbalizing in terms of what to play, no preconceptions of any kind from Trent. There were no melodies yet, and I felt that he was really just looking for his next set of clues to advance the material to the next step, hopefully infusing the stuff with a bit of my style along the way. Trent wasn’t interested in the idea of my trying to adapt my style to what he does; he was attracted to the idea of my organic guitars coexisting with his electronic keyboards. And that’s where the potential for something new existed: in the hybrid between the two.

ATTICUS ROSS

With Hesitation Marks, the songs came pretty quickly. What takes time is the constant process of building, then stripping and building and stripping and building. It never feels boring, like you’re fiddling around looking for some needle in the haystack. There’s a lot of motion; it never feels stale. That’s one of the benefits of having your own studio: you’re not looking at the clock or having to worry about someone else coming in and mixing up what you’re doing. Ultimately, the end result is the best we possibly can do. If there’s a stone, it would have been turned.

ALAN MOULDER

“Perfectionist” isn’t really the right word, because imperfection is always what we’re going for—the perfectionism of imperfection. I find Trent easy to work with, but it’s a challenge, because the bar is set high. Every time you work with him again, the bar moves—you keep trying to not repeat what you’ve done, which is difficult. He never takes the easy route on anything.

ROB SHERIDAN

Trent’s much bigger than just a musician. He’s an entertainer. He doesn’t just go in a studio, put out an album and call it a day. He works on the marketing, he works on the branding, he works on the concepts of music videos and tour productions. Trent’s experience makes him very adaptable to other situations that require creativity with an understanding of user experience. When Jimmy Iovine initially brought Trent on board at Beats, he was looking at him just as an audio guy: “Trent, why don’t you come in and take a look at some headphones.” It was by chance that Jimmy mentioned this Beats streaming music service. We ended up going in there and turning the whole project upside down. Trent has continued to hold this very high creative role in Beats Music.

SAKCHIN BENNET

Co-founder of Moment Factory, the studio that has collaborated with NIN on interactive visuals for tours since 2008

Trent’s real interest is human perception. He wants to tweak people’s minds. He’s into creating contrast in his shows, quickly changing from one vibe to another—one look is very simple and the other one burns your retina.

Production rehearsals for the Performance tour, 2007. Photography by Tamar Levine.

LEROY BENNET

Every time we put a production together, everybody else tries to catch up to it. That’s how I got involved with Beyoncé. She was playing a show in 2012 at the Revel Hotel in Atlantic City. I was brought in basically because she wanted to do exactly what we had done with Trent. I was visiting a friend who was working with Alicia Keys just to see how he was, and I go on set and it was an exact replica of the three screens we had on the Lights in the Sky tour.

ATTICUS ROSS

Trent’s radically influenced the way I work. Before I met him, because of time constraints or someone demanding something, I’d think, Oh, I guess I’ll just have to take second best. And I think that I learned that that isn’t the case. It’s okay to always aim for the best possible. You don’t have to be a dick about it, but it’s worth going the extra mile.

DAVID LYNCH

Director

I think Trent is a musical genius, and his music inspires me.

ROB SHERIDAN

When Trent signed back on to a major label at Columbia, some people looked at that as a betrayal—as if Trent had given up trying to be independent and gone back to the old system. But that move was in line with everything Trent’s been doing. It’s every bit as experimental for him to try out a full major label approach on this record as it was to do the opposite with the last one. Our core principle is not being afraid of change. It’s not trying to be stubborn and holding onto something just because it’s in your comfort zone.

RICHARD PATRICK

I went over to Trent’s house about six months ago, and we started talking about the fact that we went off and lived these lives, and although they were completely independent, we had a lot of things in common. You grow up and realize, That guy gave me my first shot. He put me in front of enough people and gave me a lot of confidence. Like, if we put our fucking minds to it, we can actually get away with this shit. This is the guy who gave me my first per diem. This is the guy who helped me get my first real fucking pair of combat boots.

ALAN MOULDER

He hasn’t really changed. He’s very much the same person; he’s just happier. And what’s happened since he’s gotten clean—he’s fearless.