January 2013: In 2005, Wesley Pentz bka Diplo went down to Atlanta to hang out at home with Maceo, the guy behind minimal anthem (and "Niggas in Paris" blueprint) "Nextel Chirp" as well as a character in the city's burgeoning weird rap scene. Eight years later, that community has birthed a second-generation superstar in Future, who has offered Maceo a sort of second life as a member of his Freebandz Gang. (The two both hail from Atlanta's Kirkwood neighborhood.) Below, revisit Maceo's first go-round, and the pre-YouTube scene that, while a relevant antecedent to today's boundary-pushing rap, has mostly disappeared from today's internet.

————

From an empty house in Atlanta, Maceo leads a new wave of lo-fi indie rap so irresistible that even the radio is snapping along.

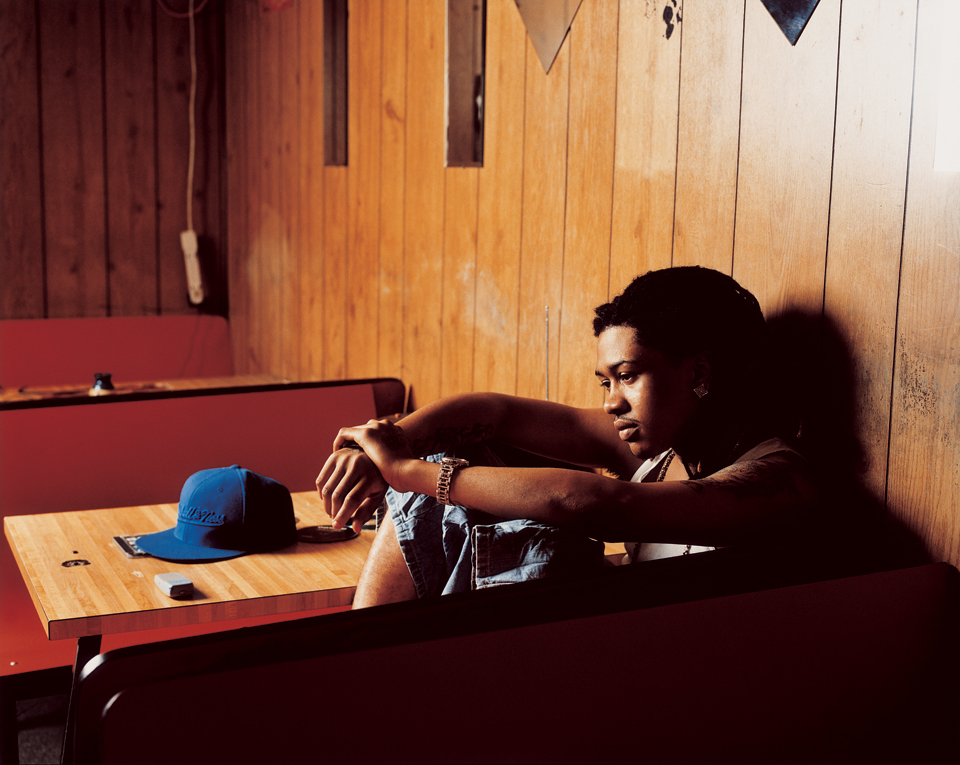

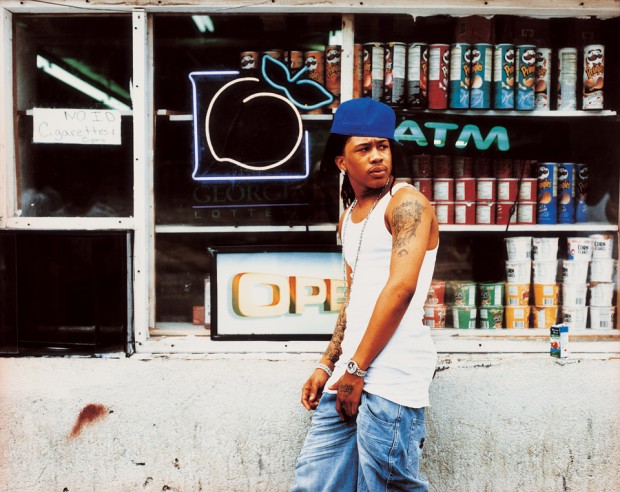

“I ain’t never rap,” says Atlanta MC Maceo. “This shit surprise me.” Maceo may be surprised, but “Nextel Chirp”—his song with his partner and label CEO Fats—has become the late summer anthem of the South, where your phone bills are as real as the work you use the phone for. The song is simple and catchy (“Don’t hit me on my Nextel Chirp/ If you trynna conversate about some motherfuckin work”)—and currently appealing to all of young black Atlanta. But Maceo is just one voice in the New South. Somewhere in Atlanta—or everywhere in Atlanta—a take-charger DIY movement is growing like weeds in the red clay behind industry headquarters. Atlanta is already the center of urban music. New York City has been dead for years. Here there are a few artists already taking advantage of the new major label power that’s all over the streets. Crime Mob, Dem Franchize Boyz and Boyz In Da Hood are beginning the push across the country with big corporate money, but just below the surface Intoxicate, Lil Weavah, D4L, Marc Decoca, Mr Bigg Tyme and the 334 Mobb are tearing up clubs and mixtapes with little more than a few “yeps,” “heys,” bass kicks and a keyboard loop.

When I meet Maceo he’s at Atlanta Medical Center. His son Maceo Jr. was born just two days ago and he’s contemplating going to get some Popeyes chicken for his baby’s momma. But he decides to take me out on the town instead. I ask him if Maceo Jr is his first kid and he says, “I hope so.” Today’s the first day of grammar school and when we leave the Medical Center along with Maceo’s partner Ran, we pass trails of kids leading out from the school buses. It seems like the movie Kids—immature yet overzealous and ambitious kids making moves, bouncing between housing complexes, eventually, maybe, making meetings and hitting studios. We ride past one youngster developing some short dreadlocks. “See we had this shit five years,” Ran says of he and Maceo’s own hair. “We the real dreads—a lot of other kids out here fakin.”

When I meet Maceo he’s at Atlanta Medical Center. His son Maceo Jr. was born just two days ago and he’s contemplating going to get some Popeyes chicken for his baby’s momma. But he decides to take me out on the town instead. I ask him if Maceo Jr is his first kid and he says, “I hope so.” Today’s the first day of grammar school and when we leave the Medical Center along with Maceo’s partner Ran, we pass trails of kids leading out from the school buses. It seems like the movie Kids—immature yet overzealous and ambitious kids making moves, bouncing between housing complexes, eventually, maybe, making meetings and hitting studios. We ride past one youngster developing some short dreadlocks. “See we had this shit five years,” Ran says of he and Maceo’s own hair. “We the real dreads—a lot of other kids out here fakin.”

Ran keeps a bandage on his right hand—apparently he was getting his car detailed and his earring went missing. As he tells it, he got too krunk and made some accusations. After breaking his hand trying to find out where the earring went, he realized it was somewhere back home and had to apologize. Ran seems to answer about ten calls in a half hour and has to go somewhere private to take them. Quick Flip is the name of Maceo’s record label and crew, and I ask him, “What’s Ran’s job in the Quick Flip team?” We’ve arrived in Kirkwood—the neighborhood where Maceo’s from—so we park, and are heading towards a house. As we approach, Maceo says, “Well, you see. There’s a job for everybody in this game,” and opens the trap house door.

“Where the Nextel charger?” is actually the first thing I hear as we walk into the house. According to a dude in the crew known as White Boy, “This is a real trap house.” You got a near-empty closet full of only Airforce Ones, one chair, a boombox with blank cds that litter the floor, and one small TV awkwardly propping a larger broken TV on top of it. There is one charger hanging out behind the armchair. It’s easily the most popular item in the apartment. Its cord dangles on the empty wall below two framed pictures of a young Bob Marley with broken glass and a one-dollar bill hanging inside the shards.

White Boy—who has the darkest skin in the apartment—sits on the couch watching UPN while he folds up a guy called Lil Psycho’s bandana proper to wear out to the club tonight. I ask White Boy (aka White Beezy), “What’s Bob Marley and the dreads got to do with your whole scene?” In like a bizarre Field Of Dreams-esque response, he replies, “…Weed…if you got weed they comin.” Maceo’s mother works at MARTA, ATL’s mass transit system—she’s worked there almost his whole life, “cleaning trains, taking tickets,” as he puts it. His father, he says, “don’t work, but I see him round Kirkwood.” Kirkwood’s a strange part of the city going through some serious growing pains. There are all sorts of new white folks moving to this residential area just East of the city center. “They even put the library, the police and the Amoco in here,” Maceo says, although he shot the video for “Hoe Sit Down” (the first single off his album Straight Out Da Pot) here, and Ran still seems to have a business. But the shiny new police station is said to be pushing work out to Decatur and the Westside. Regardless, Maceo promises the changes wont be too drastic for Atlanta proper, “’Cause black folks can’t pay two taxes.”

After an impromptu freestyle session (“I’m a tree, I’m a gat…”) from a local called Lil Beaver and a few winks from cute girls standing shoeless on the lawn, Maceo says, “I need to get weed in my blood,” and it’s off to Decatur to pick up the rest of the Quick Flip family and head to the studio for the day. Maceo plays his demo for me as we drive through his city (he has neither his own car nor a driver’s license), pumping my rental’s speakers as loud as they can go. We bounce through housing developments, whether riding on I-75, I-85 or I-20, and the music on the CD is just as serious as the smoke drippin out the window. We pass Sammy E. Coan middle school, which Maceo left just four years ago, and he gets some juice bottles at the Edgewood projects corner store. We also pass a nearby home where one of Maceo’s partners in the Cascades housing projects shot himself in the head. “I don’t now why, he just wasn’t right no more,” Maceo says.

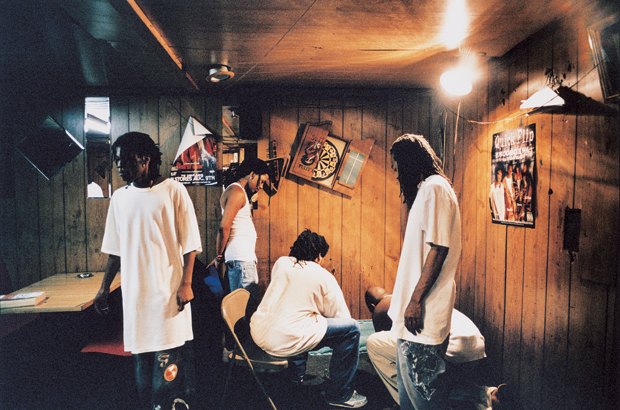

“What’s your name? Lil Syk? Lil Seke?” I ask.“Nah, man—look at him! Lil Psycho!” Lil Psycho has about 20 thick scars on his right arm. He smiles and says they’re “from when I was suicidal.” He’s wearing no shirt, but sports an African medallion, and runs to a back room and returns with a gun to pose for a camera. He fiddles around, and then goes to the opposite corner of the room to the boom box. “Check this out,” he says, and puts in a blank cassette that plays “Betcha Can’t Do It Like Me” by D4L, a group that embodies the whole movement of the new Atlanta sound. The song has fast, melodic lyrics crammed over a 70 BPM beat. The track isn’t much—its neither here nor there, and maybe that’s the whole thing. The super-minimal reigns these days as the MCs shine with a big “fuck you mayne” and all that’s left are the bare necessities. A kick drum and a finger snap, a few “yeps” (or “nopes” or “owwws”) looped on the counter beat, and a lazy key melody if you want to push it. Every song seems to float around that same 70 BPM mark, and the melodies are menacing, almost sad in their extreme energy. “Burn It Down” by Intoxicated, another up-and-coming ATL group, is next, then “White Tees” by Dem Franchize Boyz comes on. After nearly two years, the song’s almost old school to this crowd. Franchize Boyz are one of the first groups to have taken this sound nationwide and sign to a major label, and “White Tees” is a symbol of Atlanta’s New Minimalism—an everyman’s uniform of a white tee and fresh white sneakers. The songs are symphonies of no more than four sounds.

“What’s your name? Lil Syk? Lil Seke?” I ask.“Nah, man—look at him! Lil Psycho!” Lil Psycho has about 20 thick scars on his right arm. He smiles and says they’re “from when I was suicidal.” He’s wearing no shirt, but sports an African medallion, and runs to a back room and returns with a gun to pose for a camera. He fiddles around, and then goes to the opposite corner of the room to the boom box. “Check this out,” he says, and puts in a blank cassette that plays “Betcha Can’t Do It Like Me” by D4L, a group that embodies the whole movement of the new Atlanta sound. The song has fast, melodic lyrics crammed over a 70 BPM beat. The track isn’t much—its neither here nor there, and maybe that’s the whole thing. The super-minimal reigns these days as the MCs shine with a big “fuck you mayne” and all that’s left are the bare necessities. A kick drum and a finger snap, a few “yeps” (or “nopes” or “owwws”) looped on the counter beat, and a lazy key melody if you want to push it. Every song seems to float around that same 70 BPM mark, and the melodies are menacing, almost sad in their extreme energy. “Burn It Down” by Intoxicated, another up-and-coming ATL group, is next, then “White Tees” by Dem Franchize Boyz comes on. After nearly two years, the song’s almost old school to this crowd. Franchize Boyz are one of the first groups to have taken this sound nationwide and sign to a major label, and “White Tees” is a symbol of Atlanta’s New Minimalism—an everyman’s uniform of a white tee and fresh white sneakers. The songs are symphonies of no more than four sounds.

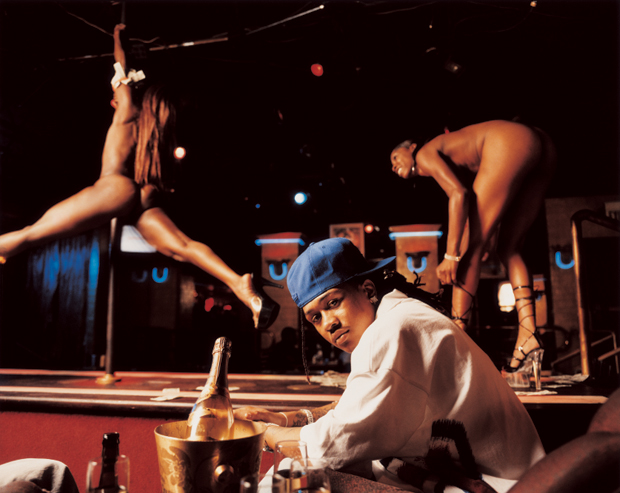

After spending the evening at Quick Flip’s studio, where Dem Franchize Boyz double-tracked verses for a new Fats song, we arrive at Club Blaze. Parking spots can be between five and 50 dollars and there are a few out there for around $30. “Let me get it for $25? I got that purp!” says Maceo. A girl who’s with the crew scrambles from person to person, trying to get singles off everyone so she can have fun with the dancers inside, too. Club Blaze is definitely not Magic City or any glossy enigma you’ve seen in all the rap videos, but this is a club for a real trap star. It’s packed on a Tuesday night. Overflow parking goes into a huge yard that’s attached. In Atlanta, a strip club is like what you might consider a regular club. From outside it sounds like the DJ is playing two copies of 2 Live Crew’s “Throw The Dick,” pitched up hard. Maceo negotiates to get our crew of nine people in the club without even getting frisked, much less having to pay. Once we’re in we head down into a VIP cave—it’s not even a room, but an empty enclosure in the back of a very packed club. “Fuck With Yo Boy” by Trap Squad is playing.

“Who’s Maceo?” says a buck naked woman. Almost scripted, Stripper Number Two says, “Don’t you know a player when you see one?” Both ask me to hold the velvet rope as they duck in and shimmy their high heels across a sticky tiled floor over to Maceo. I had already asked him an obligatory question—whether he respects the women at the strip club. “I’m a fan of anyone getting money,” he replied.

“Who’s Maceo?” says a buck naked woman. Almost scripted, Stripper Number Two says, “Don’t you know a player when you see one?” Both ask me to hold the velvet rope as they duck in and shimmy their high heels across a sticky tiled floor over to Maceo. I had already asked him an obligatory question—whether he respects the women at the strip club. “I’m a fan of anyone getting money,” he replied.

DJ Kaspa, a promoter and Maceo’s manager, tells me that he worked “Ha” by Juvenile back in ’98 when no one was fuckin with it. He brought it around to every strip club in the South and straight up broke the record. “But you see even when I was at Puff Daddy’s party, Clue pulled out the new Bad Boy single right off the press and he cleared the dancefloor,” he says. “Any DJ is taking a 50/50 risk at a party when he pulls out a new record. But at a strip club,” he continues, “no girl is gonna stop dancing!” This is where the tracks are born. They become anthems here way before “anyone hears em on 106 & Park.”

The ladies are still swirling in the VIP. “Who Maceo?” says another tired but cute stripper with pretty eyes, strollin up naked. “You can put it on me playa!” she says. After a minute of politics in the VIP, the DJ makes an announcement and Maceo and family go back to work; it’s the Amateur Dance contest. The DJ puts on Ying Yang Twins “Shake” played extremely fast, but next, by “request” of Quick Flip records, is Maceo’s “Ladies and Gentlemen." One of the best amateur dancers of the night gets out quick. Over the course of two verses, Maceo throws out what looks like a thousand dollars. He tosses out handful after handful of 50 single dollar bills on almost every measure. At the end of the song most of the crowd is speechless. Not everyone at the club knows Maceo or what song it was—or even if the song was all that good. But something just happened. Each player in the club remembers the song and how it went down. This is the birth of buzz. The host gives the girl a rake and she rushes as fast as possible to put the money in a plastic grocery bag. Some girls help by cupping their arms and rounding the money up in small piles.

Lil Psycho, kinda drunk, bends over to me and says, “I want to make something more better than what I do… Trap or die.” Maceo, meanwhile, may or may not wake up tomorrow for a promo tour through Chattanooga and Birmingham. He’s getting little money on the road now, but he knows that that’s where a rapper can make serious cash, building fan bases of dedicated kids in every small town from Colorado to Virginia. These are their anthems. “Go Sit Down” has already been on the radio for a minute, and he’s poised to push “Ladies and Gentlemen” as the follow-up. Right now, I just feel bad for the next stripper.