French cinema doesn’t get much weirder than Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. To give you an idea, the film opens with the 51-year-old director waking up in the night, sprouting a drill from his middle finger, busting through a hidden door in the wall of his bedroom and walking onto the rear balcony of a packed cinema. In another scene that starts out plausibly enough, the film’s protagonist, Monsieur Oscar (Denis Lavant), steps out of a pretty epic-looking modern mansion, waves goodbye to his family and jumps into a white stretch limo. When his driver (Edith Scob, known for her role as Dr. Génessier’s masked daughter in Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face) drops him off for his first appointment for the day, this seeming CEO emerges from the car in the guise of an elderly beggar woman, hobbling over to a busy Parisian thoroughfare to shake a metal cup.

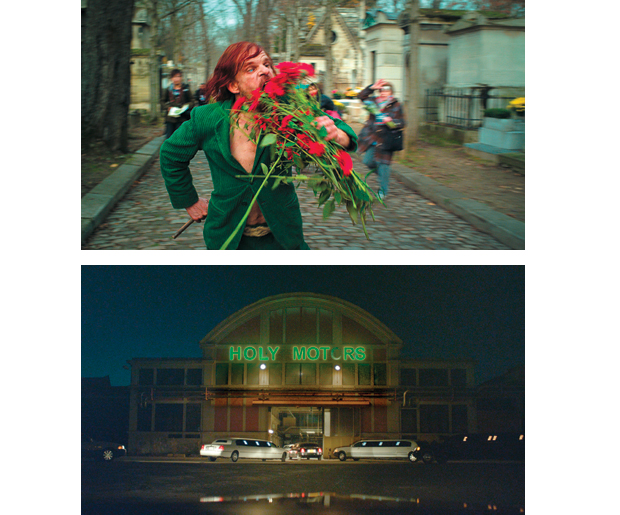

We find ourselves in a Paris where an appointment is not really an appointment in the traditional sense, where a limo doubles as a dressing room and identity is mutable to the measure of one’s resourcefulness with special effects makeup and wigs. Across Carax’s dreamily shape-shifting adventure, we see Oscar incarnate a middle class father, a motion capture stunt actor, an assassin, his target and a dying old man in a luxury apartment. During one such rendez-vous, he transforms himself into the flower-munching, trash-hoarding Monsieur Merde, a rabid-looking sewer creature whom he played in Carax’s contribution to the 2008 anthology film Tokyo!. Merde goes to graveyard and kidnaps a model (Eva Mendes) from a fashion shoot, so incapable of checking his own id that he nearly bites off the hand of a photographer in the process. And in what is perhaps the film’s most memorable sequence, Kylie Minogue pulls up in an identical limo, looking like an understudy for Jean Seberg in Godard’s Breathless and playing a former lover of Oscar’s. Presumably employed in a similarly thespian capacity, she breaks into a song about the passage of time before jumping to her death from the roof an abandoned department store. Her suicide, like most of the events in the story, is unexplained, though it could easily be an autobiographical reference to the tragic suicide of Carax’s wife, Katerina Golubeva, last year.

At Cannes, Holy Motors was greeted with an extended wrestling match between jeers and cries of joy. Early reviews were divided, some arguing that Carax was singlehandedly saving the cinema from a flagging imagination and some just as convinced that he was being willfully obtuse. In his review of the film, IndieWIRE Senior Editor Eric Kohn summed up the general confusion with the insight that Holy Motors “dares you to understand it at every turn and at the same time defies any precise explanation.” We asked Kohn and The Telegraph critic Robbie Collin, who also loved the film, to tell us what they think Holy Motors is about, and why it’s ok that it doesn’t make that much sense.

Holy Motors is a movie that’s about performance more than anything else—not just about performance in the cinema, it’s about performance in life. When the Merde section starts up where he resurrects his character from the short film he made for the Tokyo! anthology film, I thought, Oh yeah, I know what’s going on here: this is essentially a commentary on the worst aspects of our society. And then all of a sudden you’re in this beautiful, melancholic Kylie Minogue section which is a completely different universe and probably some kind of an analogy for what Carax went through when his wife committed suicide. But it’s a totally different universe of emotions, and so what I found fascinating about that is the way the movie speaks to how much reality is shifting and changing based on what we expect from it and what we bring to the table, and how cinema can reflect that in a lot of different ways.

If you look at the way the film begins, it starts with Carax himself, the director, actually walking into a movie theater, almost stumbling blindly. I think that’s a direct commentary on the way cinema is the ultimate reflection of life. I can speak from my own personal experience; movies were how I learned about the rest of the world. And I think if you look at the history of the medium, it’s always had that effect on people. The early actualités [early, short non-fiction films] that were shown in small shops around America when movies were still sort of taking off in the kinetoscope form — a lot of those things were attractive to people because they showed them reality in ways that they had never experienced it before. I think a lot of this movie is about how the cinema can guide us through those kinds of experiences without ever negating the possibility that they don’t exist. Everything in this movie seems real in some way even when it’s absurd; it’s very earnest, in a way, and that’s shocking to people because it has a lot of things that don’t make sense. The CGI sequence, for example, almost seems like it’s an actual set up for a real scenario. But we never return to that moment. We don’t know exactly what it is we are watching, and yet there is something legitimate about it that leaves an impact.

And even these passing references to things like the Franju film [Eyes Without a Face], which is where the mask comes from at the end, you know, a direct reference to a French film from a number of decades ago —these things are not there just as sly references because Carax is a cinephile. They’re there because he deeply believes in the way that cinema affects our senses. And that’s exciting.

Leos Carax plays with dream imagery and the way the human mind can make strange associations between things and make those associations seem very natural. If you take the opening scene, where you’ve got this audience sitting in a cinema, the outsides of their heads are all [soaked] in light, but the actual faces themselves are dark, and it seems like they are watching something, or absorbing something, but it’s difficult to know what or how. The relationship between the audience and whatever it is they are experiencing is not a standard cinematic one. At the end of the sequence, you’ve got noises of ships, and dockyard clanking and honking and things going on in the background, and then it cuts from that shot to this kind of Jungian, enormous black dog wandering down the cinema aisle to a shot of a building that looks quite a lot like a ship. The segue from the noise to the image is seamless because you’re mentally preparing to see a boat, then there’s something that looks a bit like a boat but of course is not a boat at all—it’s a house, but it just happens to have round windows and have walls that look something like a hull. So the strangeness of that connection doesn’t even strike you the first time you watch the film, because it’s unconscious. It’s only when you go back and see it again, when you’re looking for the way one scene links to the next, that you realize that kind of silky subconscious slide from one image to another.

Holy Motors uses the way the human mind, when it’s dreaming, can match up images and sounds and ideas in this very free-form way, but still seem to say something profound about who we are. You’ve got one man who bounces between I think 10 different roles in the course of the film, and all of them are vignettes, and they don’t really seem to have a connection to one another. Apparently we dream nine or 10 different dreams very vividly every night and the one connective thing between those dreams is that they all star us. That physical journey that Monsieur Oscar is making between these seemingly unrelated stories—it’s very similar to the journey the human mind makes every night.

Holy Motors plays in New York tonight through October 25th. See a schedule of screenings and buy tickets here.