For the past four years, Benjamin Lebrave has run Akwaaba, a digital record label that releases a huge amount of diverse African music from across the continent. He started the label in San Francisco, but, two years ago, decided to move permanently to Accra, Ghana. Since then he’s appeared on late night Angolan TV and has record deals in place with some of the continent’s top artists. Here he explains what led him to become an African music mogul.

For the past four years, Benjamin Lebrave has run Akwaaba, a digital record label that releases a huge amount of diverse African music from across the continent. He started the label in San Francisco, but, two years ago, decided to move permanently to Accra, Ghana. Since then he’s appeared on late night Angolan TV and has record deals in place with some of the continent’s top artists. Here he explains what led him to become an African music mogul.

I moved to Ghana from San Francisco in the spring of 2011, and I love it. Sometimes the culture is so different that I feel like I have to relearn almost everything I know—the art of bargaining, how to get around without street names or signs. Some of it’s daunting; some of it’s stimulating. Ghana is safe, stable and relatively cheap, and the food, despite what Francophones might say, is actually quite nice. Anybody who has fiended on a burrito can’t not love waakye. Still, I can’t say how many times I’ve been asked why I moved here. Most people have no idea what Ghana is like, and I can’t fault them. Unless things go really wrong, there is scant coverage of anything happening anywhere in Africa. And things in Ghana are going well, especially with music.

I first heard 1970s Ghanaian highlife music in 2003. Then, about a year later, a friend of mine came back from a work trip in the capital, Accra, with tapes and CDs of hiplife, an extra bouncy mishmash of hip-hop and highlife. I remember him describing outdoor bars with booming bass and bodies moving beyond what seemed kinetically possible. The seed was planted.

In 2007, I moved from Paris, where I grew up, to San Francisco, and started working for a digital music distributor. It was my job to sign up labels to get their music onto iTunes and other online stores. Between my day job and nighttime DJ gigs, I was constantly looking for new music, and I remember fruitlessly spending a lot of time trying to find Ghanaian sounds online. I found nothing on YouTube, nothing on P2P networks and certainly nothing in iTunes or any other legitimate outlet. I knew the music existed, but I had no idea why it never made its way onto the internet. I decided to take a week off of work, fly to Accra and find out what was up with this music. I didn’t have any contacts in Ghana, nor any clue really as to what I was about to uncover. I landed on a Sunday night and ended up staying in a fairly nondescript hotel in the Adabraka neighborhood, right next to an outdoor club called Strawberry. It was hopping, and as I listened to loud bass way into the early morning, I had a gut feeling that I was in the right place.

In 2007, I moved from Paris, where I grew up, to San Francisco, and started working for a digital music distributor. It was my job to sign up labels to get their music onto iTunes and other online stores. Between my day job and nighttime DJ gigs, I was constantly looking for new music, and I remember fruitlessly spending a lot of time trying to find Ghanaian sounds online. I found nothing on YouTube, nothing on P2P networks and certainly nothing in iTunes or any other legitimate outlet. I knew the music existed, but I had no idea why it never made its way onto the internet. I decided to take a week off of work, fly to Accra and find out what was up with this music. I didn’t have any contacts in Ghana, nor any clue really as to what I was about to uncover. I landed on a Sunday night and ended up staying in a fairly nondescript hotel in the Adabraka neighborhood, right next to an outdoor club called Strawberry. It was hopping, and as I listened to loud bass way into the early morning, I had a gut feeling that I was in the right place.

The following days, I somehow navigated the city and made my way to a few recording studios, where I met dozens of musicians. I realized that despite how much talent there was, there was little structure in place to push and monetize the music, especially outside of Ghana. I decided I would pursue distribution deals with a number of artists and start my own label. At the time, though, the internet was not as commonplace in Accra, which made it difficult to explain the concept behind digital distribution. But even though I was a dorky obroni (white man) with my wrinkled T-shirts and flip-flops, I did manage to sign up a handful of artists.

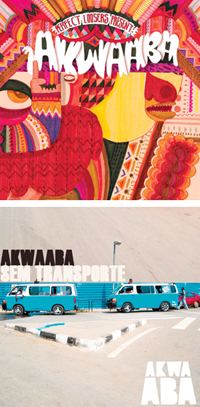

After the week ended, I went back to San Francisco and started to put together a website and a release schedule. Then I realized I needed to come up with a name for the label. Because I grew up both French and American, I’m all too used to words that are unpronounceable in one language or the other, so I wanted a word that anybody could say. I chose Akwaaba, which means “welcome” in Twi, the language spoken by most people in Ghana. “Welcome” because I wanted to welcome listeners to new African sounds, and also welcome African artists to new markets. After a fair amount of improv, Akwaaba’s first release, a compilation called Akwaaba Wo Africa, came out in the fall of 2008, quickly followed by a slew of eclectic albums from all over West Africa. In 2009, I traveled to Angola, a place I had had in mind since I stumbled across kuduro, the country’s raging dance music, on YouTube a couple of years before. I came back with enough material to release a kuduro compilation, Akwaaba Sem Transporte. Its popularity was a turning point for Akwaaba, establishing the label as a trusted source for the crossover African club music that was beginning to be known as global bass. After the kuduro compilation came a lot of remixes, a lot more releases, and little by little, Akwaaba gained momentum.

A year after Angola, in the spring of 2010, I traveled back to Ghana. On that trip it became clear that not only was Accra a place where I could find great music, it was where I needed to live. I remember coming back to my place one evening after a productive day spent in various studios. I was beat, but on the way home, I bought freshly-cut pineapple on the roadside, chatted with the locals and watched a few shockingly gorgeous girls walk by. I came back to my room to check my email, and later on I met friends for dinner. What more could I possibly need? I realized I could develop all kinds of projects if I didn’t have to leave, and so I didn’t.

Benjamin Lebrave writes a Lungu Lungu, a column about African music on this site every other week. Tonight you can catch him in New York, DJing the Qué Bajo party at Tammany Hall.