Today, Lil Wayne turns 30. He celebrated by opening a skate park in New Orleans. We're marking the occasion by re-sharing this FADER #47 cover story from 2007, where Nick Barat went down to Miami during one of Wayne's most prolific periods.

The endless nights and bottomless appetites of Lil Wayne, the most ravenous voice in rap.

Despire the grandiose implications of its neon-lit name, Miami’s Hit Factory is just a concrete box down the street from a strip-mall Publix supermarket. Engineers with Terror Squad chains chatter about SUV repairs in the parking lot, and the skies above are veiled by a constant drizzle. It’s a surprisingly glamour-free setting for one of the country’s premier recording studios, where millionaires come to create music on a nightly basis.

Inside, two small upstairs rooms house Lil Wayne’s label, Young Money Entertainment. The first is taken up almost entirely by a couch, a coffee table and a gargantuan flat-screen TV; the second is an equally modest recording space. Along with a stock ProTools setup and a single microphone, there’s little else in the room besides a snack table (Lemonheads, Gummi Lifesavers, graham crackers), the custom white guitar from the “Leather So Soft” video, and a giant framed picture of a then-teenage Wayne holding his infant daughter on the cover of the now-defunct Blaze magazine.

Inside, two small upstairs rooms house Lil Wayne’s label, Young Money Entertainment. The first is taken up almost entirely by a couch, a coffee table and a gargantuan flat-screen TV; the second is an equally modest recording space. Along with a stock ProTools setup and a single microphone, there’s little else in the room besides a snack table (Lemonheads, Gummi Lifesavers, graham crackers), the custom white guitar from the “Leather So Soft” video, and a giant framed picture of a then-teenage Wayne holding his infant daughter on the cover of the now-defunct Blaze magazine.

Wayne has recorded an average of three to four songs in that room every single night, ever since he moved his operations to Miami shortly before Hurricane Katrina. His frenzied 8PM-8AM workflow has resulted in literally hundreds of guest appearances and mixtape verses in the past year alone, and the projects only continue to ramp up. “I just did a song for Dr Dre’s Detox, a Madden 2008 song, Enrique Iglesias’ single, Jill Scott’s album, a Freeky Zeekey song, did songs for me and Game’s mixtape, Blood Brothers, did the Beyoncé and Shakira ‘Beautiful Liar’ remix, done a song with Jamie Foxx, done a song last night with Freeway, done two songs with Mya, just done a song for Ciara, and I’m on the ‘Like This’ remix for Kelly Rowland,” Wayne says between exaggerated breaths, sitting on the studio couch. I ask if he ever gets overwhelmed by the pace, and he becomes almost comically irritated. “This is not a pace, this is how I live! I wake up, smoke weed, fuck bitches, get my dick sucked—a lot—drink my drink and come here and do this shit. What am I supposed to do, take a vacation? Go to Cancun and relax? This the vacation. You got a job, but this the vacation right here. I can’t front, though—I took that line from the nigga from Kiss.”

D’Wayne Carter has been in the public eye since the beginning of his adolescence. He signed with hometown rap imprint Cash Money Records at the age of 11 and bolstered the New Orleans independent label’s rise to national prominence in the late 1990s. Rhyming as part of Cash Money supergroup Hot Boyz, Wayne was the overenthusiastic kid brother in soulja rags, croaking on songs like “Clear Da Set” about setting houses on fire and shooting people in the face. His shirtless, delinquent energy turned Hot Boyz tracks into hits (and helped permanently lock “Bling Bling” into the lexicon), and Wayne quickly found himself being molded into a solo artist.

During this period, Wayne’s stepfather died, and Cash Money founder Brian “Baby” Williams became his legal guardian. This moment is central to Wayne’s personal mythology—the two went so far as to release a duets album called Like Father, Like Son—but the reality of the situation is that more than Baby or any other surrogate, Wayne was raised by rap music. He came of age on a Cash Money tour bus, subsiding on a steady diet of hedonistic pop culture. “I just played the cut,” says Wayne. “I saw niggas start the tour and nobody know them, and then by the tenth show they can’t even say they name, they so hot. That was school for me. My first big tour was with the group Infamous Syndicate—Shawnna who’s with Ludacris and the other girl, Teefa. They were like sisters to me. Those are the kinds of things I remember.”

During this period, Wayne’s stepfather died, and Cash Money founder Brian “Baby” Williams became his legal guardian. This moment is central to Wayne’s personal mythology—the two went so far as to release a duets album called Like Father, Like Son—but the reality of the situation is that more than Baby or any other surrogate, Wayne was raised by rap music. He came of age on a Cash Money tour bus, subsiding on a steady diet of hedonistic pop culture. “I just played the cut,” says Wayne. “I saw niggas start the tour and nobody know them, and then by the tenth show they can’t even say they name, they so hot. That was school for me. My first big tour was with the group Infamous Syndicate—Shawnna who’s with Ludacris and the other girl, Teefa. They were like sisters to me. Those are the kinds of things I remember.”

Wayne’s story isn’t another cautionary tale about a child star used up and spit out by the industry. It’s more like what would have happened if Macaulay Culkin grew up to become the greatest actor of his generation. Almost a decade into their run, the Cash Money empire ran out of steam amid incarcerations, drug addictions and rampant defections, and it was up to Wayne to carry the label on his own tattooed shoulders. “If anything, [when the Hot Boyz were successful] I probably thought that in a few more years we was gonna be big as fuck. Us. I never once thought that I was gonna be big as fuck. That all changed when everyone up and left and they were looking at us like, ‘Shiiiiiit, what y’all gonna do?’” It took him a minute to refine a formula, but with the release of 2004’s Tha Carter LP, Wayne began to morph from wild child to virtuoso MC. He proclaimed himself the Greatest Rapper Alive on the outro to that album’s first single, “Bring It Back,” then set out to prove it with an unprecedented stream of follow-up releases, fusing the hyperactive spirit of his kiddie days with nimble, vowel-mangling delivery and a free-association approach to lyrical content.

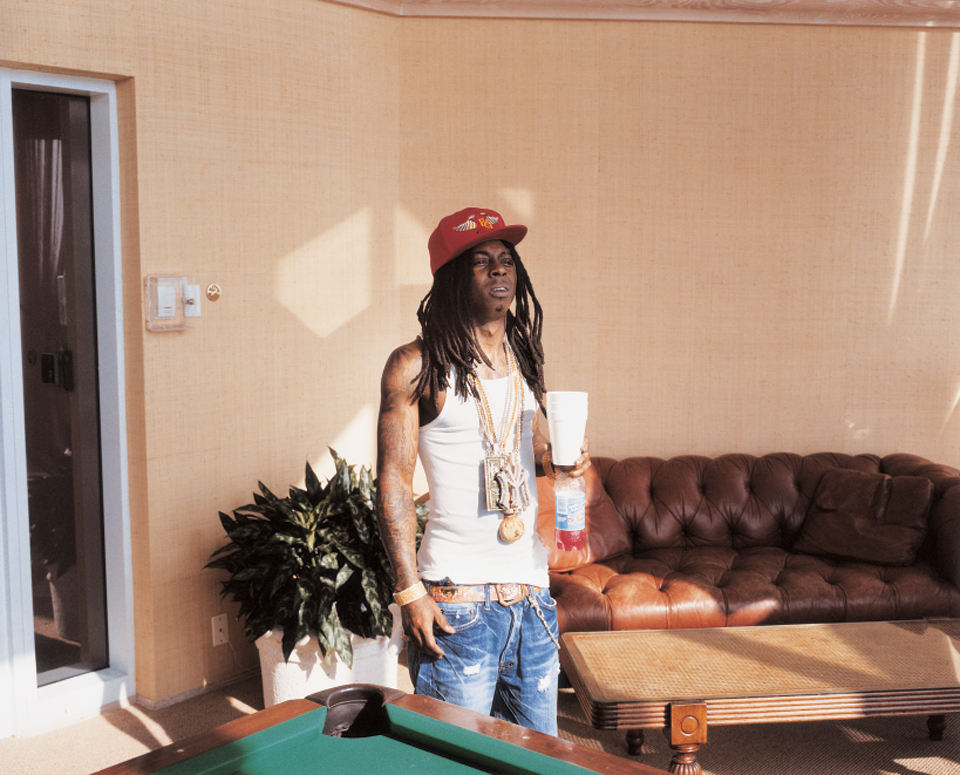

“I come at shit from a whole other angle,” says Wayne. “We’re both here with the TV on. You watching the basketball game—I don’t know what I’m watching.” Mixtapes like this spring’s marathon effort Da Drought III are peppered with Weezyisms like Play with me and it’s all-out beef/ Beef, yes, chest, feet/ Tag, bag, blood, sheets/ Yikes, yeeks, great scott/ Storch, can I borrow your yacht? There are shout-outs to Gummi Bears and Red Hots, aliens and space shuttles. He calls himself a robot and pronounces that he’s so motherfucking high he could eat a star. Chemical-enhanced sex is all over the place, and where most current rappers boast about all the drugs they’ve sold, Wayne raps about all the drugs he does, from ecstasy (I’m rollin like the Stones/ I need a water bottle) to promethazine (I’m on that syrup/ I’m on that turtle time). While we’re in the studio, the styrofoam cup of purple in Wayne’s hand and the medicine bottle peeking out of his black Gucci backpack answer any questions about how much of that talk is artistic license.

Lil Wayne’s self-proclaimed greatness turned from bluster to truth seemingly through willpower alone; he forced himself to the top by rapping—and acting—insane. Talking to Wayne in the Young Money studio, he is moody and a touch mean-spirited, but for all the effortlessly unhinged shit he says on record, Wayne isn’t a psychopath or a savant. He’s smart, though, and knows that while he has our attention, he’s still not quite sure what to do with it. “I’m not gonna get on stage like, ‘Fight the power!’ but I wanna make days shorter, nights longer…make history,” says Wayne, closing his inked-up eyelids. “I ain’t tryna make good songs, cause I been doing that since I was 12, and I ain’t tryna make a hit cause I been doing that since my first solo album. I want to make sure I’m remembered for something more important than rap music.”

Lil Wayne’s self-proclaimed greatness turned from bluster to truth seemingly through willpower alone; he forced himself to the top by rapping—and acting—insane. Talking to Wayne in the Young Money studio, he is moody and a touch mean-spirited, but for all the effortlessly unhinged shit he says on record, Wayne isn’t a psychopath or a savant. He’s smart, though, and knows that while he has our attention, he’s still not quite sure what to do with it. “I’m not gonna get on stage like, ‘Fight the power!’ but I wanna make days shorter, nights longer…make history,” says Wayne, closing his inked-up eyelids. “I ain’t tryna make good songs, cause I been doing that since I was 12, and I ain’t tryna make a hit cause I been doing that since my first solo album. I want to make sure I’m remembered for something more important than rap music.”

To that end, Wayne has recruited acclaimed (and equally ego-driven) producer Kanye West to provide beats as well as aesthetic guidance for his next album, Tha Carter III. “[West] is gonna help solidify me as an artist, not just in hip-hop,” he says. “Cause I wouldn’t even be thinking that way if I didn’t hear his beats. He got me on a song with Babyface!” Yet a different black superstar with a fondness for unbuttoned shirts may end up having even greater influence on whatever Wayne does next. “I had an iPod full of Prince from my manager, and I sat and really listened,” says Wayne, his eyes now wide and his diamond-encrusted teeth curved into a genuine smile. “And like, this nigga can’t sing! Nigga just got a distinctive-ass voice. He’s the type of nigga where you could just take him out the music and put him on the McDonald’s line like, ‘Can I take your order?’ And you’d be like, What the fuck is that? Same shit happened with my voice. I knew my shit was unique too, so I started practicing what Prince do.”

Later that night at South Beach nightspot Santo, Bigg D, producer for Mariah and Pretty Ricky, is vamping through current rap and R&B hits with his group Bottom Shelf. Dripped in diamonds, Bigg D looks more like Rick Ross’ cousin than the leader of a lounge act, but his harmonized guitar leads on “Party Like a Rockstar” are appropriately epic. Every Wednesday the group jams with whatever visiting stars might be in town; on this particular night, the guest list includes Wyclef (“One of the greatest artists of all time!” declares Bigg D) and Special Ed, who celebrates his 35th birthday with a rendition of “I Got It Made.” When Wayne takes the stage, the band lurches into a new song called “Prostitute,” which Wayne wrote with Bigg D a few days earlier. With the buttoned-down crowd hanging in rapt attention through thick Swisher smoke, Wayne shakes his dreads maniacally and harnesses his own distinctive-ass voice into a bluesy shout, singing—wailing—about a woman he would love even if she was a prostitute. If “Shooter,” Wayne’s guitar-heavy collaboration with Robin Thicke, came as a creative surprise at the end of 2006’s Tha Carter II, “Prostitute” is something else entirely—Wayne as the entire band. He’s certainly not channeling Kanye West or Prince, but finally living up to the magnetic, absurd charisma of his anything-goes mixtape verses, and hinting at becoming more than “just a rapper.”

Before the Santo performance, Wayne previewed some other new tracks in his studio. They included another Bigg D song, “Roadblock,” with a spaced-out club feel and Wayne intoning Why you putting up roadblocks?/ We could fuck like robots, a track called “Say Yes” by Carter II beatmaker Yonny, notable for Wayne’s anxiously sung acapella breakdown I would eat your fruit all night if it’s fresh, and “Step Back,” a collaboration with Freeway produced by Don Cannon that Wayne requested the engineer pull up “so they know I’m still a rapper.” Despite all these experiments and safety nets, Wayne aggressively insists there’s no master plan for Tha Carter III, other than to continue wilding out in his 500 square feet of Hit Factory each and every night from the moment he wakes up until his eyes are blood red and his voice gives out completely. “I don’t have a vision for it, cause that means you have a goal, which means you have a limit,” he says. “That question is stupid. Why do he do it? Because he is him. How do he do it? Because he is him. I’m not a psychic, I don’t see myself doing anything. I don’t expect, I live. I live!”