Gayle Wald goes from riot grrrl DJ to college professor.

Gayle Wald, a professor of English at George Washington University in Washington, DC, has spent a good part of her career writing and teaching about popular music (including to this magazine’s editor-in-chief and style editor, both GWU alumni). Though the bulk of English courses offered at the university are about literature traditionally defined, Wald stands out with syllabi that pair Billie Holiday biographies with Walter Benjamin essays and Nina Simone albums. Here, she tells us about how her days hosting a women’s-only radio show in the riot grrrl early ’90s led her to see music in a different light, ultimately inspiring an academic career largely dedicated to the power of music.

I would not have taken seriously the idea that I could write and teach about music had I not encountered feminist theory in graduate school. It was the early 1990s, and like a lot of English grad students, I was reading Luce Irigaray, Judith Butler, Audre Lorde and Gloria Anzaldúa. My studies were exhilarating, full of revelations, but I hadn’t yet translated these to sound. My “aha” moment came when I was listening to a local “women’s music” radio program and realized the songs were, without exception, acoustic, lyrical and, for lack of a better word, pretty. Fired up, I somehow found the courage to march over to the college radio station, an overstuffed bunker in one of the undergraduate dorms, to ask if I could have my own women’s music show. Apparently it was station protocol to give prospective DJs a written test of their musical knowledge. I could quote from Paradise Lost and had an informed opinion about postmodernism, but I didn’t know what a 4AD was or whether Dischord was a band or a label. The programming director must have been desperate for a female DJ, or he took pity on me, because he gave me a show.

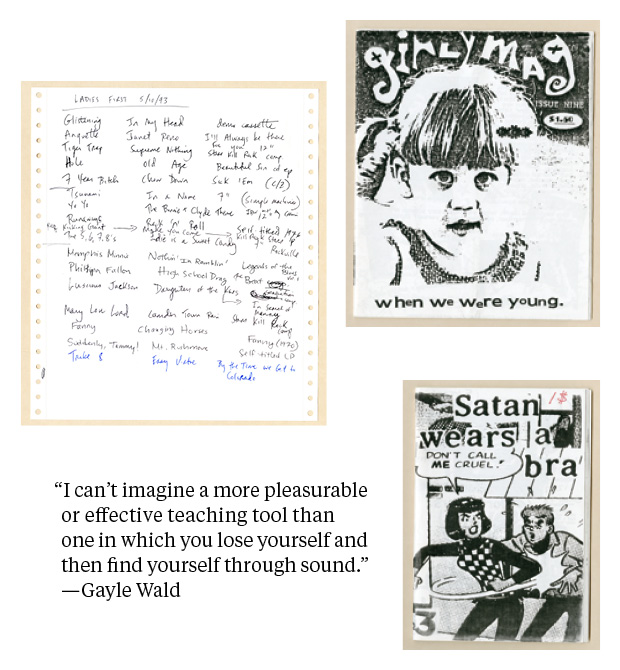

Within a month, and with a friend in tow (after the test and a look at the mess of equipment in the sound booth, my bravado had flagged and I needed help), I was hosting Ladies First, christened in homage to Queen Latifah’s breakout hit, itself a brilliant musical expression of gender trouble. In time-honored college-radio fashion, each week we concocted a mash of blues, rap, folk, punk, rock and jazz. Playing music for an unseen audience was a kick—we knew we had listeners because the studio phone would miraculously ring during ticket giveaways!—but to be perfectly honest, I was choosing songs because I wanted to hear them through my headphones. We had no rules about what we could or would play, as long as women were involved with the music. We were only diehards about that one requirement, though it was better if the music was polemical or somehow iconoclastic. The much-excoriated Yoko Ono fit neatly into this aesthetic, but so did Labelle and Sonic Youth (both Nona Hendryx and Kim Gordon were our idols). After the first Kill Rock Stars compilation arrived at the station, we had Bikini Kill’s “Feels Blind” in high rotation, Kathleen Hanna’s ferocity a jolt to the heart and the gut. The same with PJ Harvey’s Dry, when it showed up the next spring. We knew the “Women in [fill in the blank]” designation was clumsy, but it gave us license to create our own stories with the music. I never considered myself a part of riot grrrl, but, following the music’s DIY example, at some point it was nearly impossible to listen and not be inspired to think about creating something of your own. Scholarship is often pegged as the squelching of self-expression, but I found my own creative outlet in thinking and writing about popular music.

As I progressed from being a student to a professor who teaches and writes about popular music culture, I’m always after some recreation of my own experiences as a listener. Making selections for a course syllabus isn’t all that different from DJing; in both cases, you’re thinking about the mix. You want to expose your students to canonical material, but you also want them to have a chance to encounter hidden gems and new finds. You throw in new things hoping that they’ll spark an interest. When I teach, my memory of that radio station exam is always close at hand, a useful lesson in humility and a talisman to ward off know-it-all-ness, always a joy-killer in the classroom. I’ve somehow managed to keep a folder of typed playlists from Ladies First in my university office all these years. They were printed on a dot-matrix printer, the kind that had to be fed paper with holes running along the sides, so they are a bit like relics at this point. I love that I have a record of the sounds bouncing around my head during that period.

Right now I’m writing a book about the seminal PBS television show Soul!, which gave national exposure to a huge range of important black musicians in the late 1960s and early ’70s, everyone from Tito Puente, Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Marian Williams to Curtis Mayfield and the vastly underrated singer Novella Nelson. I’ve realized that the show’s producer and mastermind Ellis Haizlip was essentially also its DJ, the selector who created a story from carefully considered juxtapositions of artistic and musical performance. Like any good DJ, he never talked down to his TV audience; instead he thought constantly about how he could give this audience access to new and unfamiliar sounds.

In fact, Haizlip justified Soul!’s focus on music by noting that it could raise consciousness just as well as, and maybe even better than, a lecture about black power. He didn’t mean to disparage the movement, but he did mean to elevate the music, which TV executives at the time tended to downplay as (mere) “entertainment.” His theory of music-as-pedagogy is born out by tapes that show members of the Soul! studio audience listening to musical performances with intense concentration, their faces and bodies registering the power of their experience.

To me these images and sounds from Soul! are utopian, not just because I’m sometimes nostalgic for the music of that era (even though, paradoxically, I came to appreciate most of it well after it was made), but because new thoughts, new possibilities, new ways of being and doing are implicit in the transaction between performer and listener. Music is the medium, but, it turns out, music is also the message. I can’t imagine a more pleasurable or effective teaching tool than one in which you lose yourself and then find yourself through sound.

Images courtesy Gayle Wald Riot Grrrl Collection, Libary and Archives, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum.