Walter Van Beirendonck keeps pushing for fashion's future.

Walter Van Beirendonck loves fairy tales. He loves reading them, loves talking about them, but most importantly, he loves creating his own every six months, when he presents a new season of his menswear collection to the fashion masses looking to be enchanted all over again. A rotating ragtag bunch of characters, villains and heroes alike, have marched down Van Beirendonck’s runways: models in shiny PVC bodysuits with built-in dildos and lion tails, guys sporting green cardboard beards with bubble wrap baggy pants and butch men in dresses so sweet and campy, they look like they were frosted by Jeff Koons. If fashion’s reality is a black and white wearability, Van Bierendonck seems to have no interest in telling a straight story.

Emerging from the Antwerp Six, an influential collective of fashion designers that included Dries Van Noten and Ann Demeulemeester, all of whom came out of Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in the 1980s, Van Beirendonck distinguished himself from the pack by steering clear of the dark, serious overtones of deconstructivism and the gothy robes that many of his cohorts conjured, and instead made a habit of consistently exploding the runway with color and bold forms. Van Beirendonck has remained a rarity in a fashion world increasingly sustained on brand staples and expensive handbags, playing off seditious subcultures and throwing a laundry list of inspiration in the washing machine to see how it all might bleed together: a futuristic African rave, or a sex dungeon for animal hybrids, or in one of his most infamous, a collection based around a pair of classic, white men’s underwear, modeled by a legion of hirsute burly men—bears as they’re known in the gay community. Working with an ever-extending group of collaborators like Erwin Wurm, a visual artist who makes sculptures that look like sno-cones, and Orlan, a performance artist who pioneered horn-like body modifications and implants, Van Beirendonck transformed his models decades before Lady Gaga got cheeky.

Now in the fourth decade of his career and still working from his home base in Antwerp, where he’s also a full-time professor of fashion at the Royal Academy, Van Beirendonck has joined the ranks alongside beloved designers like Pierre Cardin who flirt with but never fully commit to mainstream success, and whose cultish appeal has had a major impact on the direction of fashion. This season, in the wake of the EU’s financial crisis, Van Beirendonck's shop faced bankruptcy and he paired down his studio to a more recession-friendly operation so as not to compromise his creativity. Despite these struggles, he has never felt more pertinent, both implicitly, with the industry’s current obsession with synthetic cyber-colors, wacky prints and rave-ready designs, and explicitly, with designers like Olivier Theyskens professing his love for Van Beirendonck and Raf Simons, an early acolyte who had his first job in fashion at Van Beirendonck’s studio in the ’90s, before taking the helm at Christian Dior. But even fantastical fairy tales are rooted in sensible life lessons, and Van Beirendonck is surprisingly practical for someone possessing such a wild imagination. On the eve of his spring 2013 collection in Paris, 30 years after his very first show in 1982, Van Beirendonck makes it clear that he’s as much interested in the ground beneath his feet as he is in the journey ahead.

Where do you generally find inspiration? Inspiration always comes at the end of the last collection, and then new things for the next are popping up. Then I take them further, start to do research. I do lots and lots of research. It’s all from books, really, and museum exhibitions. I don’t travel that much. You’d think that I do, maybe, from looking at my clothes, but I don’t. I don’t think you necessarily need to. I’d like to, but I don’t have the time, so I travel in my mind. And it’s funny, because it’s all the ethnic tribes from all over the world, from Africa, from Asia, and the rituals and dressing up and makeup that inspire me. So I have to travel through books, and I search in all different ways.

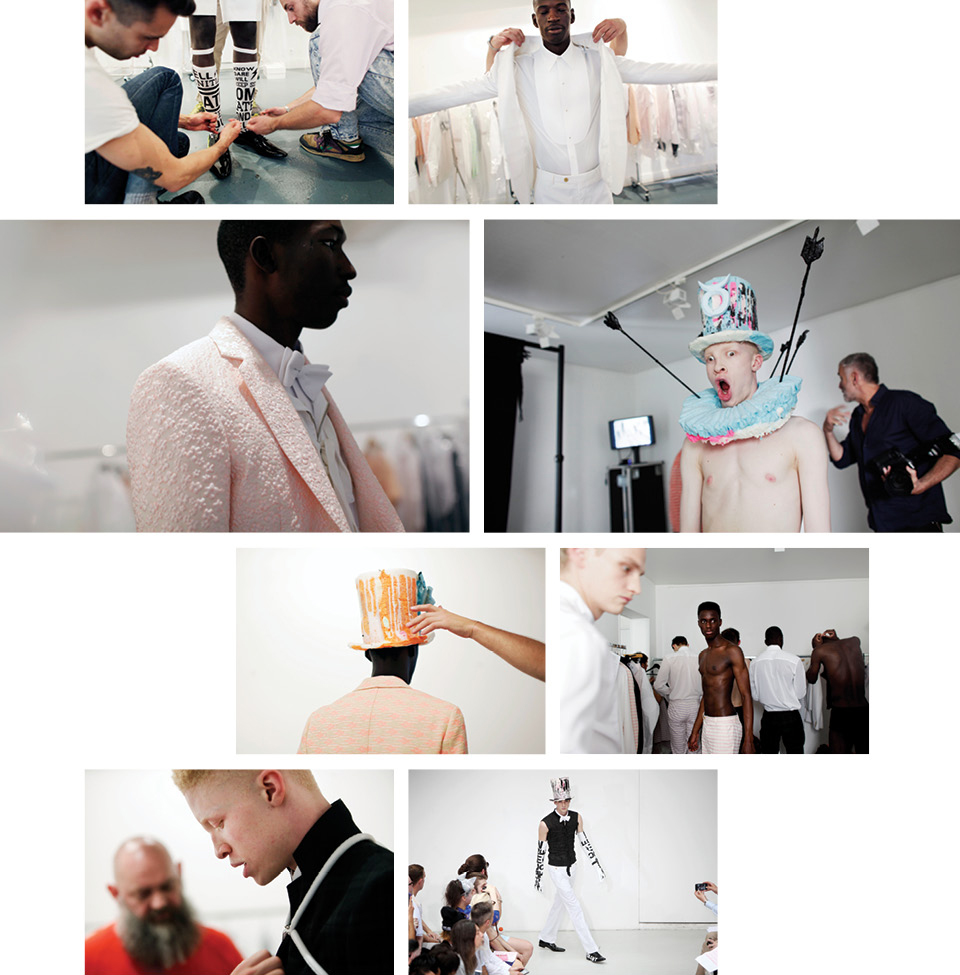

Collaboration seems to be the one constant in your collections from year to year. Why? I think it gives me almost like extra power. Working with photographers has been important for me, too. Juergen Teller, Jean-Baptiste Mondino—it gives an added dimension to my work, from outside my head. And for me, collaboration can either complement or contrast. For the hats and accessories in the spring collection, we worked with sculptor Folkert de Jong and it’s very important. It worked as a contrast to some of the formal elements. He’s young, but his work is really powerful. If you work together with another person who’s also very creative, you create a sort of energy that can become stronger than what you can do alone. It gives you wings.

Is that what being part of the Antwerp Six felt like? Kind of, yes. At the time, there was no Belgian fashion, there were no Belgian magazines, there was nothing happening. So we made it happen. That’s why when we got the first reactions in The Face, we felt almost like it was a big relief that the world could finally read about us in English. I had class with Martin Margiela and Dries Van Noten and Ann Demeulemeester and Dirk Bikkembergs, and we were just a group of friends. But we really were very ambitious, one way or another, because we felt literally locked in Antwerp. We were desperate to get out. When we went to London as a group, it helped get us noticed. At the British Designers show, the press found our names so surrealistic and difficult to pronounce that they just called us the Antwerp Six.

You’re all so different. Did you resent being lumped together just because you were all from Belgium? Of course we were totally different, but on the other hand we were all studying at the same school and did a lot of things together. We went together to Paris to see fashion shows. We loved the same things. We grew up in the period of the first Italians, like Versace, Armani. Then there were the French designers—Mugler, Montana. And then afterwards there were the Japanese, like Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo [of Comme des Garçons]. So there was a lot going on that we mutually loved, a lot of very different styles, designers who had true vision, and it showed up in our work.

What were you like at that age? I’m rather shy, and I’ve always been that way. I like being by myself, even when I was a little kid, I liked creating my own world. I’d just be in my room where I was working and reading and listening to music. It’s like creating your own cocoon, which I did and I’m still doing. I’ve never been the popular guy at the club.

How did you get into androgyny? Davie Bowie. His songs, but also his looks. Because for me I was 13, 14 years old and then he suddenly popped up with Ziggy Stardust. With that look, for me, the world opened.

Was coming out of the closet part of this self-discovery? Well, yes. I was discovering myself, I was discovering my sexuality, and then suddenly there was Bowie with this look. It was expression through look. My adolescence was during the glam rock period, and I went to a lot of concerts—I went to see Gary Glitter and Lou Reed and David Bowie—and it was an explosion. At the same moment I was discovering who I was, I was seeing men who wore weird, androgynous statement clothing. That was their expression—clothing.

Have you ever met Bowie or designed for him? No! I’d be too nervous. Bowie’s my hero.

You designed costumes for the U2 tour for PopMart. Yes, but it’s funny because I am not the biggest U2 fan. I knew the band, but it was not the band that I imagined would eventually get in contact with me. When they did, I really hesitated, but Bono liked what I was proposing. They were open. That was very surprising for me, because sometimes collaborations with pop stars can be like—first, they’re thinking about their ego and then they’re interested in the costumes. But they were really open to try things out. And I liked getting a weird reaction from their traditional fans.

Is compromising your artistic vision difficult for you? People like to ask me this, as if I can’t! I can easily compromise, because from day one, I’ve done commercial collections in addition to my own line. I mean, I’ve done things with a rainwear manufacturer. I worked for Gianfranco Ferré in Italy and right now I do a commercial children’s collection. I have to. That’s how I’ve done this all these years. That’s my advice for young designers: branch out to make a living.

Has remaining in Antwerp allowed you some separation from the fashion grind? No, I love fashion! The only reason that I stayed in Antwerp my whole life is because I teach, and I love that job. That’s the only reason. I’ve taught at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts since ’85, and I teach on a regular basis, two days a week.

Do your students inspire you in some ways? I can’t say that I’m inspired by my students, that would not be right. I try to stay away from what they’re doing because the ideas that I prefer are my own. But on the other hand, it’s nice that I’m around these young people, day in and day out—every year a new group of international people who have a lot of energy. It’s pushing me to go forward. I can’t become the old guy amongst these young people, and so I don’t.

We teach students at my school about storytelling, and that’s also what I do with my collection. So it’s not only about creating garments and the collection, it’s also about telling a story through the collections.

What kind of stories are you generally trying to tell? Fairy tales. I feel that if I’m telling a story there’s always a good and a bad side. That’s very typical of fairy tales and it’s also how reality is. Good and bad. A story needs to mirror reality. It’s not only about black, it’s also about white. And I try to let these two things come together in my collections.

Even if the idea is rooted in a universal truth, the stories you tell through your clothes seem very unique to you. That’s true. I even sized down my company just so that I could keep doing most of the designing myself, because it’s the thing that I like, and I decide every sketch and every idea. I’m very involved in the whole process because I want to keep it personal. And that’s also what I think at the end you’ll see very clearly on the catwalk—that it’s a clear decision that comes straight from my head.

You never seem to adhere to conventional ideas about physical beauty and attractiveness. In fact, you seem more interested in people who exist outside those strict molds. Yes, with bears and things like that. But not just different body shapes, also experimenting on the bodies, which is always coming back in my collections. The body modifications I did with Orlan, piercings—that’s very important, that idea of working on the body. I like everything being a canvas. I’ve experimented with a lot of different kinds of craftsmanship. Constructing and working with different techniques and materials, embroideries, and also plastics and technical materials that not every designer loves to work with. Rubber shows up a lot. Trying new things is my favorite.

Tell me about your spring collection. I was researching secret societies in the 1900s that were private and very powerful behind the scenes, and it made me really excited about a formal, proper way of dressing and the beauty of craftsmanship. I found all these books about them, and it went from there.

Why are secret societies so interesting to you? Well, for one, I liked this idea of dressing up in stiff white shirts. It started with the stiff white shirt. But also, I’m interested in the idea of secrecy, the idea of having power in being private, especially now, because the internet makes everything so unprivate. I do enjoy new technologies, but of course I’m also critical of them, because everything has a good and a bad side. I’m on Facebook, but sometimes it almost embarrasses me to see how people are throwing themselves at the unknown world. I just think it’s become very difficult today to keep a secret because of the internet, and the collection is a reaction to that.

It’s funny to hear you say that the internet scares you, because you’ve always been early in embracing technology. I embrace the future, and I think that it’s important to think in a very contemporary way, and it’s why I started so early with the technology and using the internet and making websites because I was really fascinated by that tool. My website looks like an extension of me. And that’s important. And then back in the ’90s, there were all these electronic vibes, which I loved. Techno vibes and the raves.

What did rave culture represent to you stylistically? It was just such an important evolution, both in music and in the way people looked. It created a world that sat next to my ideas about fashion. It suddenly opened a new dimension. So I was doing CD-ROMs and videos and animation, and we could add that kind of dimension to the fashion.

It sounds like you’re moving away from this in making all the crisp white suits and button-down shirts for spring, that you’re becoming increasingly interested in formality. Well, formality with a twist, because it’s never looking perfect. It’s very nonchalant, and so the colors are open, the bow ties are hanging. Everything always has to be with a twist. Plus, I haven’t really done it, so it’s new for me to try white shirts and suits. I know I’m not so known for formal clothing, but I like that. It’s a nice challenge to find a good balance between how everybody knows me from the past and also how I can push it forward into the future.

Every time you start to feel hemmed in, you shift directions. Well, I’ve always been working with colors and prints, and now of course I see so many colors and prints—everybody’s jumping onto prints. So I’m pushing myself in directions away from what other people are suddenly doing too much of. It’s not that I don’t like colors or prints, but this isn’t just about what I like: for me it’s more tempting to limit myself, to go in another direction. That way, I keep surprising myself. And I have this freedom to do that because I have very loyal clients.

Who is the Walter Van Beirendonck client? Let’s just say that he’s flexible. I’m lucky and I don’t know that every designer has that. I can go where I want because they will follow. My clients are rather particular, and in America, for example, I only have like four or five stores. Because you have to really follow my way of thinking and all the department stores are afraid of me. So I really need these loyal stores. I develop relationships with these places.

Do you like the fashion industry? Do you hang out with the fashion crowd? There are definitely a lot of fashion people whom I am not interested in, but I also never want to exclude the fashion world. And there are a number of fashion designers I like. I knew Alexander McQueen when he was first starting out, and we liked each other very much. I know Rei Kawakubo. I met her a few times and we have a very good relationship; she was important to me when I was starting out. So there are people in the fashion world whom I really admire and really like, and whom I try to meet one way or another. Vivienne Westwood, too.

What do you think of your old intern Raf Simons becoming the head designer at Christian Dior? I think it’s an amazing opportunity. It’s incredible that he is going to do it. It’s like a dream for a designer, to get into such a house and to have this possibility, and I’m sure that he’s going to do fantastic things. I think coming from the avant-garde to such a big house can work very well, and I think that bringing Raf to Dior is a very interesting way of thinking about fashion. It’s similar to Galliano—someone new, different, and that can give a very fresh approach. Fashion needs that.

Could you ever picture yourself working for a giant house? It would have to be at a place that makes sense for me. One of my big dreams would be to work for a house like Courrèges or Cardin, those were my heroes when I was young. And I can perfectly imagine doing that kind of work. I mean, there are a lot of brands I wouldn’t be interested in.

Are you a good businessman? I have to be, but I don’t like it. It’s definitely one of my weaker points, and I make decisions with my heart, and that’s definitely not always the best business decision. I want freedom.

How have you felt the impact of the EU’s financial crisis? You feel it very strongly, with what’s happening with Greece and what’s happening now in Spain also. You feel a little bit desperate, which is of course not good for the economy. Because people are getting scared and they’re afraid of what the future will bring, and that’s also creating a negative attitude toward consuming, which isn’t good for me. I’m worried, of course. I think it’s rather natural, if you see what’s going on in the world and how it’s changed the last 10 years. Maybe it’s not such a bright moment.

Your work makes you seem more like an optimist than a pessimist, though. Of course. Here I am, I keep on. I’m rather optimistic because even in the worst periods, I find enough energy to go forward. I think that we have to keep on believing, because that’s the only way things change. I’m always hopeful. I don’t want to be scared of the future.