After a surprising ascendence, The xx learn to balance sensibility with popularity.

The xx is spread out across two circular wooden tables in the drab lunchroom of Music Bank, a large warehouse in an industrial complex in South London. It’s early May, and the trio is preparing for three shows—their first in over a year and a half—essentially dress rehearsals before a headlining performance at the Primavera Sound festival in Spain later in the month. The first show will be held at Electrowerkz, a tiny club in an alley. Here at Music Bank, the band has been practicing a handful of songs from their forthcoming second album Coexist as well as relearning the old ones that have fallen out of practice. It’s tedious, monotonous work, more akin to memorizing multiplication tables than making art. Commensurately, the enthusiasm meter in the room is at negative a billion. The only thing providing anyone with any reason for excitement is dessert. Along with the rented rehearsal space comes a private chef, and they are over the moon about the banoffee pie, a banana and cream concoction he’s ingeniously served individual portions of into wineglasses. They eat it and, looking up from smartphones and The Daily Mail, encourage me to to do the same, before filing back into a gated elevator down to the big blue rehearsal space.

The band is set up in the back by the windows, where they repeatedly play their 30-minute set. Being party to this private concert is at first extremely exciting, but over and over, with no one to share it with, it morphs, as bassist Oliver Sim succinctly and depressingly puts it, into “a gig no one showed up to.” He knows what that feels like. “When our album came out, everyone was like, Where did this band come from?” says guitarist Romy Madley-Croft. “What was kind of funny is we had been playing for three years in shit pubs. This time around we didn’t have the opportunity to go and play at a shit pub, basically. It would have actually been constructive.” This is her modest way of saying they are too famous to do things the way they used to; The xx playing anywhere is an event, and a show at a “shit pub” would cause pandemonium.

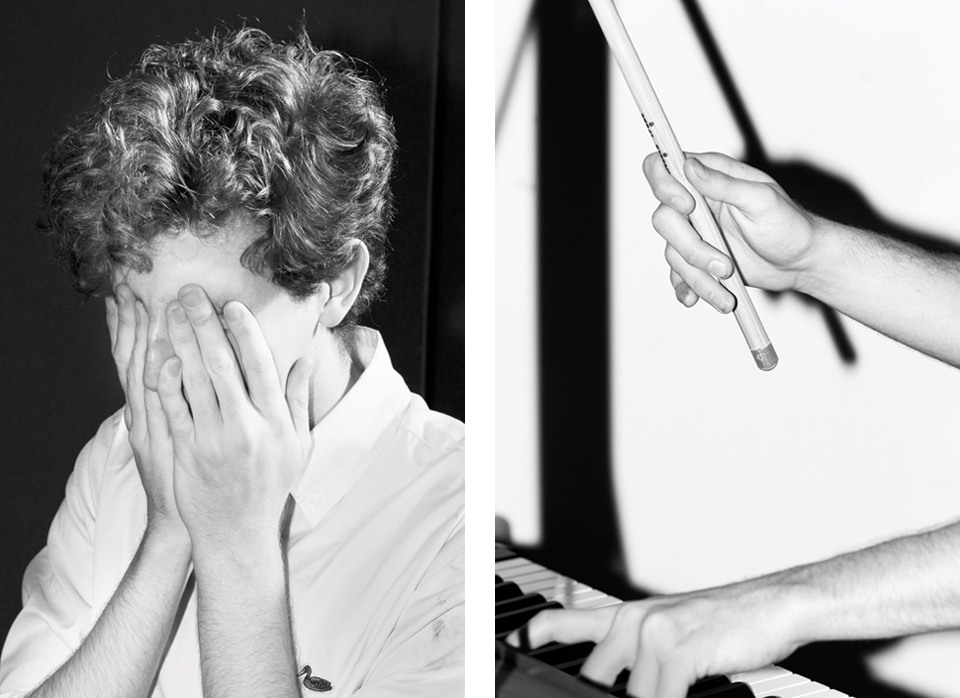

That pandemonium has made them a lot of money and, like any exploratory young musicians, they’ve splurged on new equipment. When one of percussionist Jamie Smith’s new machines goes mute, there’s a groupthink to get it in gear. “Is it a DI thing? Sounds like a DI thing,” says Craig Donaldson, their new Scottish monitor engineer. He and stage manger Terry Yoshinaga and stage tech Sam Hair huddle around Smith’s uncooperative equipment like a couple of mechanics around an open hood, a position they’ll regularly assume over various pieces of equipment the rest of the week. When The xx began playing live, Smith’s gear consisted of a single MPC, a standard issue sampler. He now has, in addition to a pair of MPCs, a rented 909 drum machine, four hanging V-Pad drums, a blue steel pan, a pair of CDJs, assorted drums and cymbals and a gang of anonymous synthesizers. His equipment, as Madley-Croft puts it, “had babies.” Displayed in a sprawl behind hers and Sim’s comparatively slim setups, his equipment looks like a floor display at an electronics store.

That pandemonium has made them a lot of money and, like any exploratory young musicians, they’ve splurged on new equipment. When one of percussionist Jamie Smith’s new machines goes mute, there’s a groupthink to get it in gear. “Is it a DI thing? Sounds like a DI thing,” says Craig Donaldson, their new Scottish monitor engineer. He and stage manger Terry Yoshinaga and stage tech Sam Hair huddle around Smith’s uncooperative equipment like a couple of mechanics around an open hood, a position they’ll regularly assume over various pieces of equipment the rest of the week. When The xx began playing live, Smith’s gear consisted of a single MPC, a standard issue sampler. He now has, in addition to a pair of MPCs, a rented 909 drum machine, four hanging V-Pad drums, a blue steel pan, a pair of CDJs, assorted drums and cymbals and a gang of anonymous synthesizers. His equipment, as Madley-Croft puts it, “had babies.” Displayed in a sprawl behind hers and Sim’s comparatively slim setups, his equipment looks like a floor display at an electronics store.

Though they’ve played the songs on their debut hundreds of times, they all acknowledge a need not to abandon early material, so they’ve opted to play around with some of the older songs. For “Islands,” a standout from their self-titled debut, Smith has reworked the complex opening passage he typically plays on the MPC for the hanging V-Pads, and he crosses and re-crosses his arms, repeatedly missing the right notes. “I feel like I’m getting a workout,” says Smith. His newfound mobility is particularly surprising, given his stationary presence throughout their tour for xx. Later, keeping time behind the CDJs, he exaggeratedly nods his head and shimmies his shoulder. “I actually quite enjoy having to dance behind the decks,” Smith says. “I’d like to do that on stage more because over the last three years, I’ve just been concentrating on pressing the right button.” This is a particularly dry understatement. Smith has often looked like he was working the late shift at a canning factory instead of playing in a band. Being backbone to two passionate and seductive lead singers may have anchored the trio, but it unquestionably seems much less fun. He seems to have finally tired of tedium. The change is especially evident in the neck hickey he shows up to practice with the next day.

Two years ago, I spent three days on tour with the band for a profile on Smith. He’d just completed a reworking of Gil Scott-Heron’s last album, I’m New Here, which the duo re-titled We’re New Here. It was well received, and gave him a more central position in the spotlight, for which he was not prepared. During that tour, Smith was extremely shy and though he eventually warmed by default of elongated proxy, he didn’t talk much. He’s still laconic, but his demeanor is less rigid. His appearance has morphed as well, with the loss of baby fat on his face. He has the air of a young aristocrat, unfailingly polite but only cursorily interested in outside agendas, which is likely the effect of years of having the demeanor of a hermit but still being forced to do nonstop interviews. Because he spent the band’s time off actively DJing to promote We’re New Here, along with his solo debut as Jamie xx, a 12-inch single, he’s grown accustomed to people’s interest in his brain. Comparatively, Sim and Madley-Croft overflow with light pleasantries and seem born with gobs of the social ease Smith works hard to produce. They routinely express pride in his individual success and, during their year off, more content with a traditional view of vacation, often casually followed Smith around to gigs in Europe; Madley-Croft says they were his “groupies.”

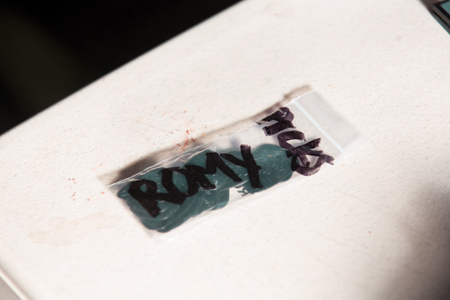

Another ego boost for Smith came in the form of Candian superstar and xx megafan Drake, for whom Smith produced the title track from his wildly popular sophomore album, Take Care. “[Drake’s a] top bloke,” says Smith. “I was entering another world when working with him. A very interesting diversion that I am looking forward to exploring more.” Smith still has a Drake tour VIP pass stuck to the inside lining of his jacket. Still, the allure of fame is not strong enough to overpower a wry, British wit. When I mention to him that I’d watched an interview with Drake where he says that Smith will have a “big presence” on his next album, he says, “Yeah, I saw that, too.”

Another ego boost for Smith came in the form of Candian superstar and xx megafan Drake, for whom Smith produced the title track from his wildly popular sophomore album, Take Care. “[Drake’s a] top bloke,” says Smith. “I was entering another world when working with him. A very interesting diversion that I am looking forward to exploring more.” Smith still has a Drake tour VIP pass stuck to the inside lining of his jacket. Still, the allure of fame is not strong enough to overpower a wry, British wit. When I mention to him that I’d watched an interview with Drake where he says that Smith will have a “big presence” on his next album, he says, “Yeah, I saw that, too.”

The xx recorded their debut in a small studio in the office of their record label, Young Turks. The running joke is that they kept being mistaken for interns. After selling 1.5 million records internationally and winning the Mercury Prize, Britain’s award for album of the year, they were allowed to trade up for new digs. Coexist was recorded in an xx clubhouse of sorts, an apartment in the Angel neighborhood that they’ve retrofitted into a studio. The rented split-level apartment is in a gated complex, abutted by a large McDonald’s whose late-night allure the band claims to have withstood through the entire five months spent recording. “The day we master our album we’re gonna feast,” says Sim. It appears that no one has ever actually feasted inside the studio so much as eaten various types of processed foods, which you can tell from the snack wrappers littering the floor. There are a lot of socks lying around, too. The only substantial piece of furniture is the piano, and Sim and Smith generally avoid it like one might ignore a broken old television nobody wants to drag to the curb. Upstairs is slightly neater. They point out the vocal booth, which is a nook curtained off with a scrim of black velvet. Smith sits at his big computer, opens up iTunes and presses play on a mix he says he made for his family last Christmas. It starts with Destiny’s Child.

Sim, tall and solid, folds himself into a broken office chair, looking truly comfortable here, as he does almost everywhere. He’s handsome, with a strong nose and broad brow, and if he is, at 22, too young to seem paternal, he still displays an easy authority, like a kindly bouncer. An ever-present black topcoat and chunky black boots help complete the look. When not following Smith around this past year, he’s stayed home in London, growing into his newfound adulthood. Quietly nursing beer after beer and lamenting the hassles of the workday, he seems much older than his years, until he reminds you he isn’t. “When you’re on tour, you might as well be like a newborn baby, you’re taken anywhere you need to go. If you’re going to be at a party, you’re taken there,” he says. “I came home and if I needed to be somewhere I’d automatically expect someone to take me, I’d just be sitting there, and then there’s that realization, that, Okay I need to look after myself now. We started touring when we were 18, but when we came back we were 21.” In that time, most of their peers attended college. “I’ve been really content in London. In the time that I’ve been gone and come back, it was really nicely unfamiliar, but I think I’m excited now to start leaving.” Before that happens, they still have to finish the record. Acutely aware that, as its mixer, the task is largely up to him, Smith’s attention is continually drawn to the computer. “Making this album was an illuminating self-education in the differences between what makes a great record producer and a great artist,” he says. “It was tricky at times because it seems where I need to be is somewhere in between.” Their manager later says they’ll let the lease lapse on this space soon, but for the time being, Smith is holed up here, tweaking during the last free moments before the hullabaloo of a two-year album promo cycle begins again.

Sim, tall and solid, folds himself into a broken office chair, looking truly comfortable here, as he does almost everywhere. He’s handsome, with a strong nose and broad brow, and if he is, at 22, too young to seem paternal, he still displays an easy authority, like a kindly bouncer. An ever-present black topcoat and chunky black boots help complete the look. When not following Smith around this past year, he’s stayed home in London, growing into his newfound adulthood. Quietly nursing beer after beer and lamenting the hassles of the workday, he seems much older than his years, until he reminds you he isn’t. “When you’re on tour, you might as well be like a newborn baby, you’re taken anywhere you need to go. If you’re going to be at a party, you’re taken there,” he says. “I came home and if I needed to be somewhere I’d automatically expect someone to take me, I’d just be sitting there, and then there’s that realization, that, Okay I need to look after myself now. We started touring when we were 18, but when we came back we were 21.” In that time, most of their peers attended college. “I’ve been really content in London. In the time that I’ve been gone and come back, it was really nicely unfamiliar, but I think I’m excited now to start leaving.” Before that happens, they still have to finish the record. Acutely aware that, as its mixer, the task is largely up to him, Smith’s attention is continually drawn to the computer. “Making this album was an illuminating self-education in the differences between what makes a great record producer and a great artist,” he says. “It was tricky at times because it seems where I need to be is somewhere in between.” Their manager later says they’ll let the lease lapse on this space soon, but for the time being, Smith is holed up here, tweaking during the last free moments before the hullabaloo of a two-year album promo cycle begins again.

Unlike xx, which achieved its sublimity through a uniformly flat tone, Coexist is more varied. “Fiction” is propelled by drums in a way nothing on xx ever approached; “Reunion” utilizes a kitchen sink of percussion, from steel pan (a staple of Smith’s solo work) to mimeographed, raw kick drum. But while the potpourri drum work may be the band’s fresh coat of paint, Coexist’s strongest improvement is the simple progress Madley-Croft and Sim have made as songwriters. They have been friends since they were toddlers and the telekinesis present on xx has only been sharpened by the last few years of onstage refinement. At its most disjointed, xx felt like melodies they’d composed with a backing by Smith, a fact underscored by their buoyant personalities and his active disinterest in basic pleasantries. On Coexist, that gap has narrowed. “There’s been times where maybe we’ve felt a song was complete, and we’ve been proven wrong and [Smith’s] taken it to a completely different place,” Sim says. The vividness of many of those new places makes xx feel thin by comparison, like the work of teenagers, which, of course, they were.

The band’s appeal has always been that their songs hew closer to sketches than fully fleshed beings, but Coexist shows the complexity possible within that skeletal framework. “I think it’s a lighter record, a lot lighter,” says Sim. That upswing is palpable. All three members of the band cite a growing interest in house music, and its four-four drive and general ebullience has seeped into the album. “We were kind of experimenting with songs that were slightly more electronic, which isn’t bad, it’s just different,” says Madley-Croft. It’s Smith’s job in mixing—as well as producing the record—to moderate that experimentation. To get everything right, he works meticulously, admitting that he’ll spend hours on a single snare sound. That perfectionism may be the reason for the album’s potency, but it’s also responsible for its initial release date being pushed back by three months.

On the far end from experimentation, though, there are some songs that can feel like xx paint-by-numbers. On album opener “Angels,” a simple love song driven by the sweet refrain Being as in love with you as I am, Sim occasionally drops in with a dollop of bass, never overstaying his welcome. Madley-Croft continues, With words unspoken/ A silent devotion/ I know you’re what I need. At first it’s striking and elegant, but with repeated listens it begins to sound cheesy, somewhere between Rumi and Hallmark, and will certainly be a hit at weddings. It’s a great song, but maybe for someone else to sing. The xx are better when they’re bummed.

“I’ve always been a massive fan of really sad dance music,” says Madley-Croft. “You’ve got a room full of people dancing and the lyrics are actually just awful.” This is true of songs like “Chained,” where, as a duo, they lament Did I hold you too tight?/ Did I not let enough light in? No one is wishing misery and turmoil on the group, but whatever bit of that they’ve experienced, they’ve turned into great fodder. For the first time, Madley-Croft says she’s done this by design, crafting songs not just from personal experience but also from an amalgam of others’. “I’ve written quite a bit more from observation, which I didn’t do so much on the first album,” she says. “It didn’t feel like getting into the role of a character. It’s not—I guess it is like poetry. I asked people for certain scenarios they had been in, you know feeling like, This had happened to me, I felt this way because this, and it got me into that mind frame of thinking like, Oh how would I have felt?” Sim looks at her a bit flabbergasted; he did not know this. When I ask him about his romantic relationships and songwriting, he flashes a Cheshire cat grin and says, “I don’t talk about that to anyone.” Both Madley-Croft and Sim point to the queen of despondency Sade as an inspiration and her time-tested brand of emoting is not far from their own. While that could point to a long career as artists, they could also graduate to a career in songwriting for others. Anyone can write heartbreak songs, but it’s a rare skill to make them actually touching.

In the years since their debut, their sparse sound has been aped wildly. xx’s barebones approach spans genres, making everyone from global pop stars to deep dubstep producers want to move as lithely. In 2009, Madley-Croft met Shakira at the BBC studios in London where both artists had been performing. “We were sitting on a wall outside the BBC and she came up and her bodyguards parted and it was little Shakira, and she says, ‘Hi!’ And I was like, Wow!” says Madley-Croft. “I found out recently that she’s a big fan of The Cure and stuff.” A short time after their meeting, Shakira covered “Islands” onstage at the massive Glastonbury Festival and that fall officially released her version on her album Sale el Sol. Instrumentally, it’s a fairly faithful cover, as though she were working from a skeletal demo they’d written just for her. Their highest profile endorsement the next year came from Rihanna, whose Stargate-produced song “Drunk on Love” is essentially just a beefed up version of their “Intro.” “Us being fans of such massive pop stars, Rihanna and Beyoncé, loving and studying pop songs, I think it’d be fun and weird and interesting to have someone sing it and take it to a different place, something you write,” says Madley-Croft, seemingly forgetting that this has already happened. Though Stargate unwisely replaced some of the guitars with synthesizers and “Intro” has no words save for a breathy hum, all three members of the band are credited as songwriters.

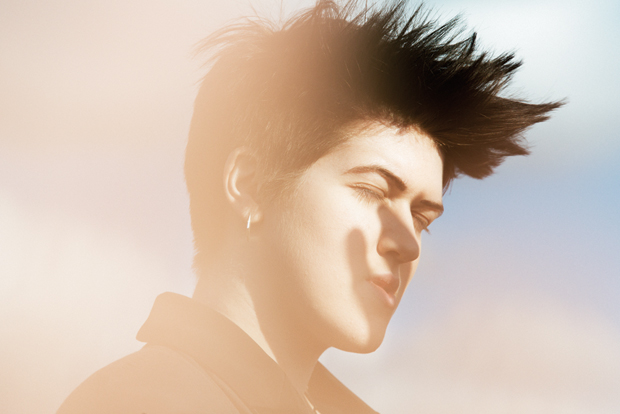

In the morning before the last day of rehearsal, Madley-Croft grabs a quick coffee. She’d turned in early the night before, dyed her hair at home, then got up in the morning to get it cut. It’s early, but she looks made up, just like she does every day, pale and dressed in a black blazer and black pants. It’s easy to view her as a den mother. What was so effective about xx was its vulnerability, which on Coexist has been recast as brazenness, largely with her lead. “When we were doing interviews on our last tour, people would ask us if we were going to think about the fact that lots of people would hear it and Oliver said yes, and I said no. I just knew that I wanted to write exactly what I was going through, because I want to connect with it still, and have some emotional thing, and not be guarded,” she says. “In the end, I think we just went with what we were feeling anyway. You kind of forget that people will hear it.” While both albums work in ethereal fields, Coexist no longer utilizes youth as the secret ingredient in its witches’ brew. But they’ve adapted in kind. “I like playing the old songs with the new songs and realizing that it does fit, in my mind. So it’s not like old album, new album too much. I think it really just is further along down the road. I’m very nervous about people hearing it,” she says. “I guess like anyone with anything, you want people to like it.”

In the morning before the last day of rehearsal, Madley-Croft grabs a quick coffee. She’d turned in early the night before, dyed her hair at home, then got up in the morning to get it cut. It’s early, but she looks made up, just like she does every day, pale and dressed in a black blazer and black pants. It’s easy to view her as a den mother. What was so effective about xx was its vulnerability, which on Coexist has been recast as brazenness, largely with her lead. “When we were doing interviews on our last tour, people would ask us if we were going to think about the fact that lots of people would hear it and Oliver said yes, and I said no. I just knew that I wanted to write exactly what I was going through, because I want to connect with it still, and have some emotional thing, and not be guarded,” she says. “In the end, I think we just went with what we were feeling anyway. You kind of forget that people will hear it.” While both albums work in ethereal fields, Coexist no longer utilizes youth as the secret ingredient in its witches’ brew. But they’ve adapted in kind. “I like playing the old songs with the new songs and realizing that it does fit, in my mind. So it’s not like old album, new album too much. I think it really just is further along down the road. I’m very nervous about people hearing it,” she says. “I guess like anyone with anything, you want people to like it.”

Stopping by the café in a taxi to pick her up, Smith briefly takes off his headphones to say good morning. He has a computer on his lap, mixing Coexist. We pick up Sim, who lives, he says, in “Jack the Ripper territory,” and talk turns to their newly launched Tumblr and the upkeep of the band’s Facebook page. Occasionally they post photos and Madley-Croft wants to put up a snapshot of Smith in the rehearsal space, alone at a drum machine. She passes it around for a consensus. Smith briefly looks up from his computer. “Could do,” he says. “Does it need a caption?” she asks. “Explains itself,” he says. One comment on the photo reads, “gngntjegibnsejgifvmkfldpgiojgiod;mka;vfkma;ebga;ongo;svmsbFUCK.” It currently has 1,617 likes.

The last day of rehearsal is playful. Sim, like a cat, finds a sliver of sunlight late in the afternoon and drags a chair into its warmth. He takes off his shoes and cracks open a Sprite. This inspires everyone else to crack Sprites. Smith gives Sam Hair a brief lesson on programming his 909 drum machine, which quickly devolves into a jam session. They both bop for a long time. Madley-Croft fishes out a gigantic Polaroid camera and takes photos of everyone in the room. Tomorrow is their first day off in a week—their last before the show—and it feels like the last day of school before a one-day summer. Tonight, they’re all planning on going to a big rave.

Being so young and naked, it’s difficult to pin—or want to pin—any creation myth on The xx. To most of their audience, they were born full-grown. In the few years of their public existence you can mark their emergence into adulthood through publicity photographs, the progressively more conservative haircuts, the upgrade of black hoodies for black designer jackets, expensive clothes they’ve largely been given for free. It’s a trajectory not dissimilar to Drake or Rihanna’s, but those stars are loved; The xx is beloved. The difference may mean millions of fans or dollars, but it’s allowed them creative freedom and a general sense of everydayness. In the past year, all three members of the group purchased apartments in the Shoreditch neighborhood of East London, a neighborhood that is medium-expensive and canonized cool, not up-and-coming cool. They praise its convenience, though living among your target audience can have its perils, however self-fulfilling. “You would think, Oh, band moves to Shoreditch,” says Madley-Croft. “I felt like a walking cliché.” But they’re a big band inside a little band, their outsize influence incompletely translated to their real lives. Even if the times when it does tease its way in don’t seem so bad. “Every now and then a cab driver will be like, Oh yeah, ‘Islands’ and you’ll be like, Ha, this is great!” says Madley-Croft. “Once me and Oliver were in the back of this cab, and [the driver] was like, ‘Oh, my son is going to be so happy.’ It was lovely.” What draws a cabbie to The xx is the same as what draws a big personality like Shakira—pop music’s ability to synthesize the personally pivotal into the universally mundane.

Being so young and naked, it’s difficult to pin—or want to pin—any creation myth on The xx. To most of their audience, they were born full-grown. In the few years of their public existence you can mark their emergence into adulthood through publicity photographs, the progressively more conservative haircuts, the upgrade of black hoodies for black designer jackets, expensive clothes they’ve largely been given for free. It’s a trajectory not dissimilar to Drake or Rihanna’s, but those stars are loved; The xx is beloved. The difference may mean millions of fans or dollars, but it’s allowed them creative freedom and a general sense of everydayness. In the past year, all three members of the group purchased apartments in the Shoreditch neighborhood of East London, a neighborhood that is medium-expensive and canonized cool, not up-and-coming cool. They praise its convenience, though living among your target audience can have its perils, however self-fulfilling. “You would think, Oh, band moves to Shoreditch,” says Madley-Croft. “I felt like a walking cliché.” But they’re a big band inside a little band, their outsize influence incompletely translated to their real lives. Even if the times when it does tease its way in don’t seem so bad. “Every now and then a cab driver will be like, Oh yeah, ‘Islands’ and you’ll be like, Ha, this is great!” says Madley-Croft. “Once me and Oliver were in the back of this cab, and [the driver] was like, ‘Oh, my son is going to be so happy.’ It was lovely.” What draws a cabbie to The xx is the same as what draws a big personality like Shakira—pop music’s ability to synthesize the personally pivotal into the universally mundane.

Fittingly, there is no backstage at Electrowerkz, so before The xx take the stage for their comeback show, they have to walk through the crowd. A pocket of the band’s friends have gathered near stage left. They look cooler than the rest of the audience members, with more severe haircuts and more expensive fabrics, generally better looking. Madley-Croft’s girlfriend, clothing designer Hannah Marshall, takes a lot of photos with her iPhone using an app called Noir. “This is our first show in almost two years,” says Sim. Everyone cheers. They start with “Angels” and though there is a hush, it’s far from pin-drop silent. The chatter continues throughout the rest of the show, with little deference to the new songs. The old ones prompt sing-a-longs. The concert feels more like a technicality, something to talk about later more than actually enjoy. Smith is the first one to bungle his part, twice flubbing the introduction to “Islands,” which he’d tirelessly tried to work out on the V-Pads earlier that the week, but relegated back to the MPC. “We’ve been in the studio the past year and a half, so I’m not going to downplay how terrifying this is,” Sim says. When they finish their set, he makes a peculiar announcement. “We can’t do an encore because we’d have to walk through the crowd.” There’s a dutiful smattering of applause and they begin to play “Intro.” People cheer at the familiar notes. Afterwards they still have to walk through the crowd. There are a lot of light bulb flashes.