Yayoi Kusama’s captivating autobiography, Infinity Net.

Yayoi Kusama’s captivating autobiography, Infinity Net.

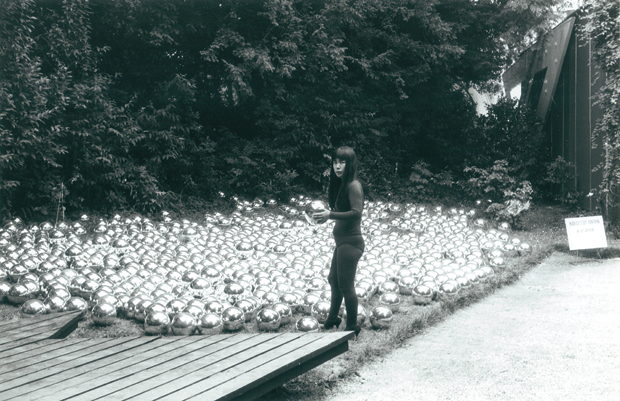

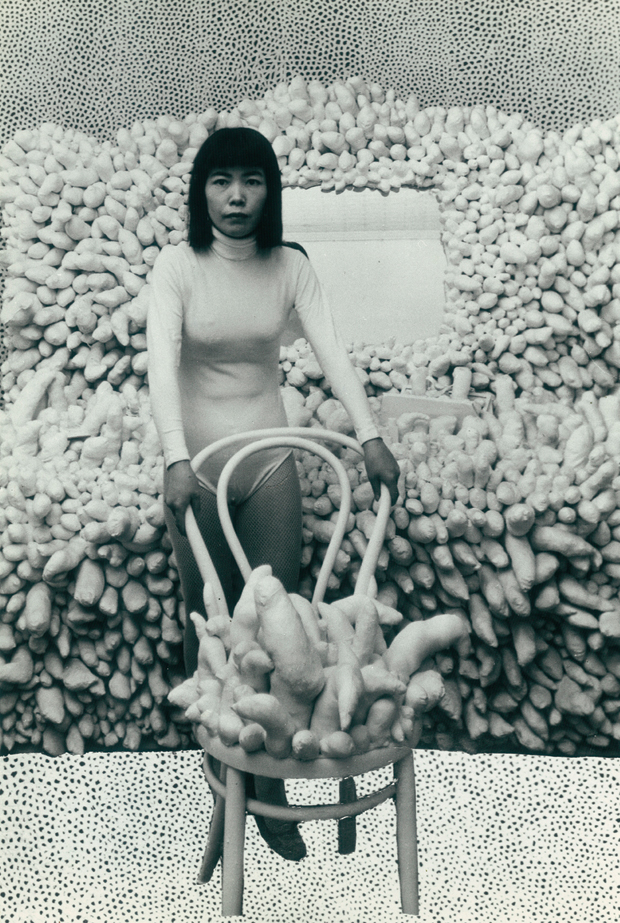

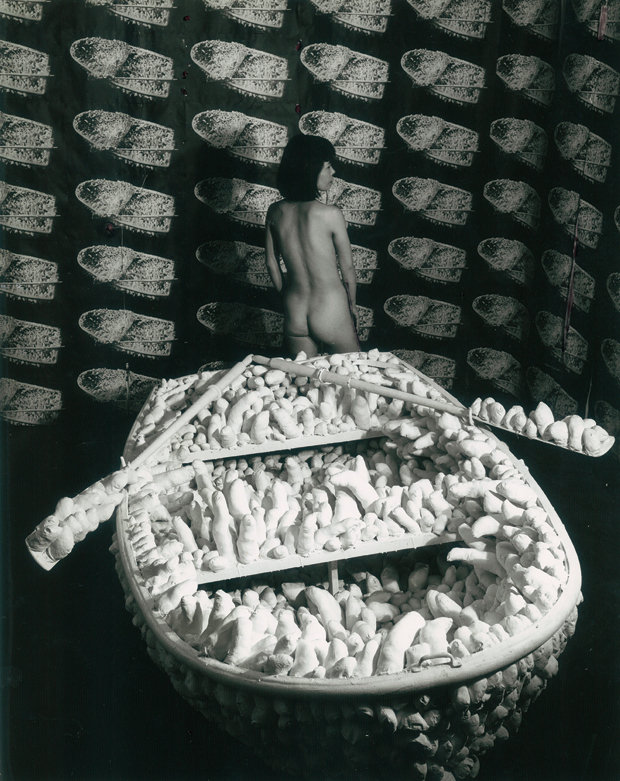

Yayoi Kusama has been making conceptual, “obsessive” art for well over a half-century. Since emigrating from Japan in the late ’50s and bursting quietly onto the New York avant-garde scene with her painstakingly studied “infinity nets” (large swaths covered in polka dots), Kusama has approached art as a means of coping with mental illness. Her art—which ranges from painting, to collage, to nude “happenings” and environmental installations—is comprised of elaborate compositions, which she clinically describes as acts of “depersonalization,” a way in which to normalize her fears, anxieties and visions through repetition. She’s touched and influenced many artists and peers like Donald Judd, Joseph Cornell (with whom she had a significant but chaste romantic relationship) and Claes Oldenburg, as well as Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom Kusama corresponded since she was an aspiring young artist in Japan. Since 1977, Kusama has lived voluntarily in a psychiatric institution, and continues to produce work, commuting to a studio across the street. In 2008, Christie’s auctioned a Kusama piece for $5.1 million, at that time, a record sum for any living female artist. The following is an excerpt from her autobiography, Infinity Net, which has been translated into English for the first time and will be published in conjunction with a brand new exhibition at London’s Tate Modern (February 9-June 5) and will travel to the Whitney in New York this summer. In it, she describes her earliest encounters with psychosis, and in turn, the seeds of her artistic life.

Violet Voices

I was twenty-seven when I went to the United States. If I had not made it to the USA, I do not think I would be who I am today. The environment I grew up in was exceedingly conservative, and escaping it at the earliest possible moment had been my dream, and my struggle. I would have preferred to leave much earlier but was delayed because of the difficulty of traveling overseas in those days and the fierce opposition of my family—in particular my mother. Still, I made it, and I am glad I did. If I had stayed in Japan, I would never have grown as I have, either as an artist or as a human being. America is really the country that raised me, and I owe what I have become to her.

I was born on 22 March 1929, in Matsumoto City, Nagano Prefecture, the youngest child of Kamon and Shigeru Kusama. My family was an old one, of high social standing, having for the past century or so managed wholesale seed nurseries on vast tracts of land. Each day a crowd of workers came to collect the seeds of violets or zinnias or whatever it might be, for resale all over Japan. We had six large hothouses, which were so rare in those days that sometimes groups of schoolchildren came on field trips to look at them. Propertied and wealthy, my family supported local painters and had a standard understanding of art. But the prospect of their youngest child becoming a painter was a different matter altogether.

My grandfather was an ambitious man, active in both business and politics, and my mother had inherited his blood and his fiery temperament. My father married into the family and adopted the Kusama name. The tension and pressure that arose from that arrangement was certainly responsible to a large degree for the oppressive atmosphere that dominated my infancy and childhood. I entered Kamata Elementary School in 1935. By 1941, the year I matriculated at Matsumoto First Girls’ High School, the war that had been going on for so long had ignited into the Second World War. And it was from about that time that I began to experience regular visual and aural hallucinations—seeing auras around objects, or hearing the speech of plants and animals.

From a very young age I used to carry my sketchbook down to the seed-harvesting grounds. I would sit among beds of violets, lost in thought. One day I suddenly looked up to find that each and every violet had its own individual, human-like facial expression, and to my astonishment they were all talking to me. The voices quickly grew in number and volume, until the sound of them hurt my ears. I had thought that only human beings could speak, so I was surprised that the violets were using words to communicate. They were all like little human faces looking at me. I was so terrified that my legs began shaking.

I struggled to my feet and ran as fast as I could, all the way back to the house. I was almost there when our dog took up chase, barking at me—in human words. Astonished, I tried to say something, but now my voice was a dog’s voice. I dashed inside the house in a state of panic, thinking: What’s going on? What’s happening to me? Pale and trembling, I wriggled into a cupboard and closed the door, and only then was I able to breathe. Sitting there in the dark, thinking back over what had just happened, I could not tell if it had been real or just some sort of dream.

At other times I would be walking a path through the fields at nightfall, the sky getting darker and darker. I would look up to see a burst of radiance along the jagged, mountainous skyline, and suddenly things would be flashing and glittering all around me. So many different images leaped into my eyes that I was left dazzled and dumbfounded.

Whenever things like this happened, I would hurry back home and draw what I had just seen in my sketchbook, churning out one sketch after another. At such times, I was not here. I was in a separate world, and I was drawing in order to document the sights I saw there. I had several notebooks full of these hallucinations. Recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes. That is the origin of my pictures.

All I did every day was draw. Images rose up one after another, so fast that I had difficulty capturing them all. And it is the same today, after more than sixty years of drawing and painting. My main intention has always been to record the images before they vanish. Take, for example, my oldest work, The Parting, which I made when I was very sad about being separated from a certain person. In the cupboard I found a piece of material that matched my feelings, and I clung to it and dried my tears with it before using it as my canvas. This was before I had ever even heard the words “collage” or “assemblage.”

From my very earliest memories I have felt imprisoned by the walls of my eyes and ears and heart, upon which have been emblazoned all manner of things—nature, the universe, people and blood and flowers—in the form of wondrous, horrifying, or mysterious events. The sinister but nameless somethings that are forever peering out of the shadows of the spirit have for long years driven me half mad, pursuing me with an obsessive and almost vengeful tenacity.

The only way for me to elude these furtive apparitions is to recreate them visually with paint, pen, or pencil in an attempt to decipher what they are; to gain control over them by remembering and drawing each one that flashes through the haze, sinks to the bottom of the sea, stirs my blood, or incites destructive rage.

Psychiatry was not as accepted in my youth as it is now, and I had to struggle on my own with the anxiety, to say nothing of the visions and hallucinations that at times overwhelmed me. I feared exposure of my secret—that I had lost some of my hearing. The childhood asthma I suffered was triggered by friction between my self and the external world. There was no one with whom I could discuss these issues. The question of man–woman relations was taboo, the world of adults was wrapped in enigmas, and I felt completely cut off from my parents and society: all of this was infuriatingly unfair and—literally—maddening.

It was as if I had already given up hope for myself and my surroundings from the time I was in my mother’s womb. Painting was a fever born of desperation, the only way for me to go on living in this world. You might therefore say that my painting originated in a primal, intuitive way that had little to do with the notion of “art.”

Reprinted with permission from. Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, by Yayoi Kusama, published by the University of Chicago Press. © Tate 2011. All rights reserved.