Gerlan Marcel is leading the charge for a brighter fashion future.

Gerlan Marcel is leading the charge for a brighter fashion future.

Seated in a small, windowless studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, a salon smock draped around her shoulders, Gerlan Marcel is art directing a side pony like it’s her job. She’s getting ready to be photographed alongside her Spring 2012 “Mall Witch” finale piece: a neon-green body-con bustier dress with corset lacing, constructed entirely of “slime.” A hired stylist is doing her best to take cues and plot the length of Marcel’s gradient blonde mane right where she wants it—high enough to create “sprigs,” “tight on the right,” but “slightly lumpy” on the left, “not-so-perfectly perfect”—and, in a last ditch effort, inserts a long, U-shaped pin that miraculously perks the pony. Marcel is, once again, all dimples and levity. “You’ve got all the tricks,” she tssks, tempering any diva-like pretension with a witheringly funny story about how this same look landed her on a popular fashion magazine’s what not to do list. “They called me a ‘grown’ woman and my hair a ‘rat’s nest.’” At 35, Marcel is a decade older than many of her customers, but aside from occasionally referring to friends and acquaintances as “kids,” she seems unfazed by the age divide—like her clothes, her sensibility skews young. For the shoot she’s also chosen an endearingly unfussy ensemble: A T-shirt for the Brooklyn band Light Asylum with an occultish-looking design and a matching denim puffer vest/jeans combo covered in an all-over soft indigo-blue Gerlan Jeans logo pattern from her Fall 2011 “Bless These Jeans” collection. On her feet are pair of drab-colored high-heeled duck boots, an unholy union that would seem ironic if it weren’t such a commitment.

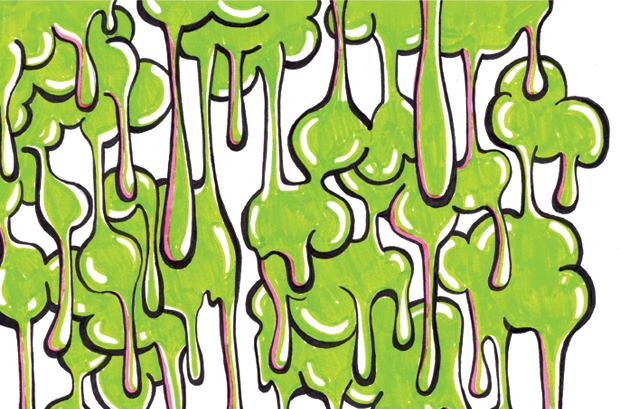

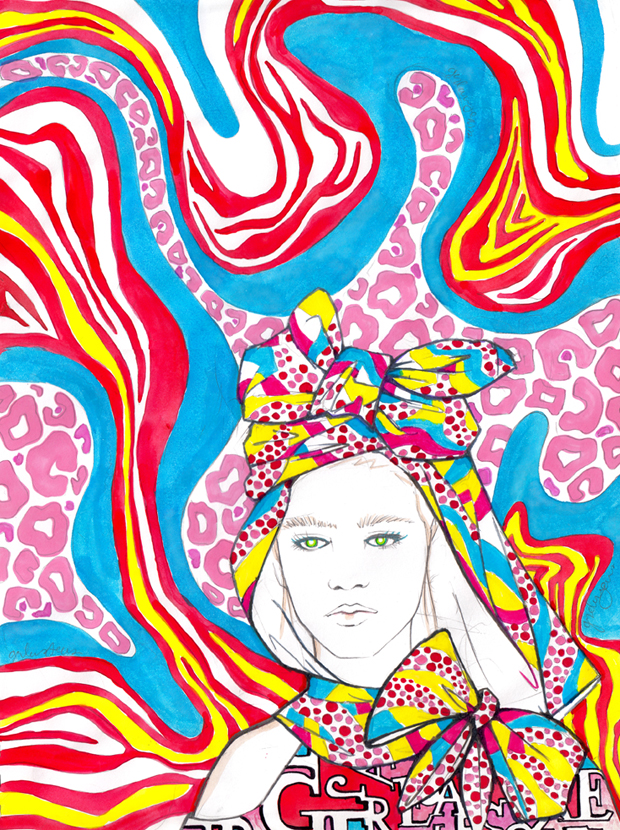

For her “Mall Witch” collection, Marcel conjured an ode to that stylistic darkness particular to adolescents—the brand-obsessed brooding girl with a bad attitude and Manic Panic hair. The women’s clothing played with body-conscious silhouettes—cropped shirts and bra tops, one of which was a cheeky take on the torpedo bra fashioned out of two tiny witch hats. The prints were skulls, X motifs, cartoonish printed (and real!) slime, a pattern made up of hand-drawn yearbook faces scribbled out with “brat” written on the side, a T-shirt that says: Don’t look at me, don’t talk to me. Black, pink and neon green predominated, with a full-spectrum of color played out on the models’ heads. “‘Mall Witch’ was about taking those iconic shapes that you see at Hot Topic and then giving them the respect they’ve always deserved. It’s [about] being able to take something that’s kind of a gross idea, and manipulate it into something else.”

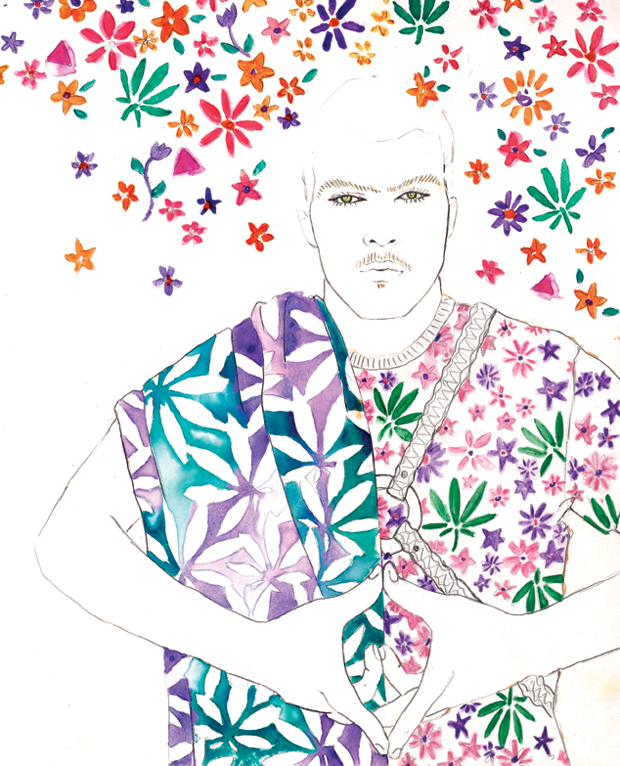

Drawing from the rich tradition of jeans brands that dominated popular fashion in the ’80s and ’90s, namely Jean-Paul Gaultier’s diffusion line, Gaultier Jean’s, Guess, and ’80s Benetton and Esprit, Marcel is determined to bring design with a capital D back to mass-market retail, or as she calls it, a diffusion line with none of the diffusion. It’s usually the goal for any serious designer to be well respected on the runway and in the pages of Vogue, but Marcel wants foremost to be popular with people. The production costs for her bespoke prints, denim and jersey basics, however, price her out of reach for most mainstream buyers, so she remains in stockist limbo, her clothes retailing only in hip boutiques like Opening Ceremony. “There seemed to be a lot more design happening on a mass-market level a decade ago,” Marcel says, touching on Esprit’s sophisticated aesthetic that went all the way down to the look of the stores (designed by Memphis founder Ettore Sottsass). “Half the brands [today] are licensed—literally no one is designing them. Somebody prints out 4,000 pages from Style.com and then it gets filtered through a Chinese factory somewhere and made out of Halloween fabric and shipped back to the States.” In this way, Marcel’s decision to root Gerlan Jeans in denim and sportswear is what she believes will enable her to execute her creative vision within the realistic terms of production. “To me, it’s not about rewriting the silhouette,” she says. “It’s more about the sophistication of sportswear. It’s all about mixing wearability with something that’s still designed. A lot of people can’t get their brains around it, they see print and it’s ‘wacky,’ it’s ‘kooky,’ it’s ‘funky,’ but it’s not being wacky for wacky’s sake.”

Marcel is not alone in leading the charge towards a brighter, poppier future. There’s a strong set of designers who have come up in the past few years, who are playing with ideas of cartoon couture, pop art and subverted sportswear, like UK designer Carri Munden’s label Cassette Playa, Finnish designer Daniel Palillo and New York Hood by Air designer and DJ Shayne Oliver, whom Marcel cites as a compatriot. Munden is the most trail-blazing and high-profile of the pack, having enjoyed early attention from Lady Gaga’s fashion guru and Mugler designer Nicola Formichetti, who bought Munden’s thesis collection for his Tokyo-based shop SIDE BY SIDE. She was nominated for Britain’s Menswear Designer of the Year award in 2007 alongside Alexander McQueen and Christopher Bailey, solidifying her stature by both industry standards and the avant-garde street scene. Munden, who regularly styles for magazines like Dazed & Confused and SuperSuper as well as a slew of pop stars like MIA and Dizzee Rascal, has stated that she sees her work as very concept-driven and interested in the idea of being “a living cartoon.” Her website is a pixelated maelstrom of animated GIFs and internet memes, which smacks of the early-internet aesthetic permeating the current 2D and 3D design conversation. Well into the new year, a lingering Christmas wish reads: ± <3 * H a p p y Y u l e * <3 ± + h e r e s 2 t h e A p o c a l y p s e / n e w a g e / 2012 ☺

If fashion is forever rooted in elements of escapism and performance, this band of designers possesses a combined visual language that speaks directly to a generation socialized through screens and image aggregators. As Munden says in an early interview with the blog Lipstick Tracez, her influences include but are not limited to: cartoons, comics, computer games, Keith Haring, Memphis, tribal and graphic primitive patterns, geometric shapes, the colors from a packet of Wotsits candy, orange, green and blue. In other words, if this aesthetic has its way, the future of fashion will be an insane miasma of hyper-colored prints and internet logic, false nostalgia and context-less appropriation.

To seek out inspiration for his Spring 2012 collection, Finnish designer Daniel Palillo found himself trolling mundane American big-box stores in New York (where he was visiting on a grant) for inspiration, to create his bold, graphic basics—skulls with Marge Simpson ’fros, sweat shants with a heavy metal-looking type that say DESTROY and oversized jumpers printed to look like soccer balls. It’s an aesthetic that capitalizes on the boring, the kitsch, and sumblimates it. “I would go to Best Buy, the electronics store. I could spend three hours in there, and [then] I would go to the one in Walmart and spend another three hours there,” explains Palillo. “The people who [shop] there have really inspiring styles of wearing clothes, putting random things together, and it looks super cool on them.” In other words, just some kids wearing mismatched clothes and buying their electronics is inspiration enough, if you have imagination. Gerlan echoes his sentiment: “I’ve gotten a lot of inspiration from teens on the subway. Their bra straps are everywhere. You know, they have a tank-top on and then another tank-top over it. This one’s short and that one’s long and they’ve got two belts and like four straps.” This was directly translated into the “Mall Witch” collection in the form of a tight-fitting pencil skirt that falls, in multicolored layers of upside-down camisole tops, down to the knee.

Aside from a general predilection for cartoon, fantasy and color, another commonality each of these designers shares is a strong market-base in East Asia. In a country like Japan, where cosplay (short for costume play, a popular subculture in which teens dress up as their favorite manga, anime and made-up characters) and a rich tradition of trends that borderline on dress-up mingled with a strong interest in technology and pop culture, this is unsurprising. “Japan is like a pastiche of lots of different styles, but punk and hip-hop are two of the ones that are very important, and the sort of girl culture—kawaii cute, Lolita-ish is their own sort of indigenous one. But they all sort of coexist and co-mingle,” explains Valerie Steele, Director and Chief Curator of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, who organized the show Japan Fashion Now at the museum last year. “It’s true especially with [Japanese] menswear brands like Phenomenon, who have been popular with American hip-hop performers. It doesn’t really sell in the US, but when I featured Phenomenon in my show, it was one of the most popular of the whole show because it was so out there, sort of science fictiony and sexy and his range of inspiration was so demented, from insects to bondage, to hip-hop music.” Japan’s fiendish youth culture has exerted a lot of influence on the behavior of the markets in Hong Kong, Korea and Taiwan, and on the Gerlan Jeans Facebook page, Marcel regularly reblogs pictures of her designs posted in the popular Japanese street fashion magazine, FRUiTS, which photographer/publisher Shoichi Aoki started in 1997 to document the fantastic street styles he was seeing in Tokyo’s Harajuku district. His rule has always been to photograph kids who put together their own, unique style and weren’t heavily influenced by brands. Interestingly, these designers have also won favor with K- and J-Pop stars, themselves highly manufactured products of the music industry.

For her part, Marcel looks to East Asia as a viable market and perhaps the most logical means to realizing the big vision of Gerlan Jeans. “There are only a few channels for talented designers outside the mainstream to get attention. Namely, win Ecco Domani or CFDA [awards for emerging designers],” Marcel explains. “Vogue understands that they have got to, in some way, embrace some element of [the underground], otherwise they’re not telling the full story, but I don’t think they really understand where the energy is really coming from.” Britain has traditionally done a better job nurturing their up-and-comers, with Fashion Week side shows like Fashion East that helped launch the nascent careers of designers like Jonathan Saunders and Carri Munden. “The London showrooms bring all those designers out for a Vogue dinner after every season, but what advocate is doing that for designers here?” Gerlan asks. “I’m an underground designer, and the irony of all this, of course, is that I’m the least underground, I’m über connected. Everything is like, Twitter and Facebook and Tumblr, and what’s on the street, and what the kids are doing now, which are the most over-ground things. Somehow, Telfar and Hood By Air were all labeled underground, which is supposed to be somewhat flattering, but that’s not what it’s about for me. That’s not what it’s about for any of those kids.” As if to prove her point, this microcosm of the New York scene was given significant real estate in a recent issue of the British magazine SuperSuper. The issue includes a story on Marcel, as well as Kingdom and Venus X, two musician/DJs with whom she has collaborated for her runway shows.

True to below-the-radar form, Marcel launched a Kickstarter campaign in early 2010 called, “Gerlan Jeans: The Return to the Runway” to help raise money for her Gerlan Jeans Spring 2011 collection. The campaign, which featured exclusive online giveaways to backers and regular video updates, exceeded its pledged goal of $17,500. This was in no small part due to Marcel’s indefatigable spirit, and her aforementioned connectivity. In the campaign launch video, she pops up onto the screen, reciting a script that’s as hyperbolic as her hair (a braided, balled-out prosthetic version of that same side pony) while a frenzy of cartoons and prints flash behind her. It’s a mess of high camp and Ryan Trecartin-like delirium, with Marcel driving home the Gerlan Jeans mission: “Become an agent of change, contribute to the global collective of print and color; help shape the future of fashion!” At one point, she even throws her hands up in the air as if she just stuck a backflip off a human pyramid. When Marcel says Gerlan Jeans is where, “the runways of Paris meet the malls of the world,” it’s clear she means something very different than the similar design edict at J. Crew, where designs from the runway are interpreted (or straight-up borrowed), repackaged and disseminated to the mass-market J. Crew customer. Marcel is more interested in distilling the creative approach of high fashion into her own mass-market sportswear basics.

She is also not alone in this aim. Before moving to New York and launching Gerlan Jeans in 2009, Marcel worked designing prints and graphics for fashion’s current l’enfant terrible, Jeremy Scott. Over the past few years, Scott, whose foray into the fashion world was inauspiciously pooh-poohed by Vogue contributing editor André Leon Talley, has gained remarkable footing, thanks in part, to his Jeremy Scott for Adidas Originals label, high-profile pop endorsements, and the public’s growing interest in humor, hyperbole and caricature in popular fashion—a stepping out from the dark shadow of the understated chic “downtown” goth style championed by Rick Owens and Alexander Wang, runway designers with rampant market appeal. Marcel had a hand in designing five collections worth of signature prints for Scott—bold French-fry patterns, camo/combat Care Bears, a hundred dollar bill in Scott’s own image—and also enjoys quieter but important endorsement from artists like Beyoncé, the K-pop supergroup 2NE1 and Lil Wayne (one of the few who actually paid for a large, direct order of Gerlan Jeans pieces, though Marcel also says that sales of the T-shirt version of Beyoncé’s “Video Phone” dress practically cover her monthly rent). It’s easy to see the creative push and pull of influence in Jeremy Scott and Gerlan Jeans collections, from their witty typographic appropriations, to gender-bending silhouettes and pop culture and sportswear influences. Curiously, all of the six collections that Marcel worked on for Scott are absent from the Style.com runway archive—a bleak, seven-year gap between 2003-2010, in which none of his shows were listed or reviewed—a sign that fashion’s favor has been capricious at best, and loathsome at worst.

The designer Patricia Field, whose eponymous boutique has been a New York mainstay since the ’70s, has always been a champion of this brand of bombastic, colorful dressing. She carries Gerlan Jeans and, at times, even employs Marcel to design prints for her own label. Despite her cult following (so large in Asia, in fact, that she runs a Japanese version of her blog), Field is really best known for her styling for Sex and the City, and she jokes that many people come to her store expecting to find those clothes only to be overwhelmed by racks of Carrie Bradshaw’s most outrageous looks times three. But Field also runs a business with a bottom line, so she’s as attuned to market drivers as she is to her own personal taste. “Right now, in my store, it’s very ’90s and flashy and sexy. There seems to be, in the past couple of years, a sort of an increase in that consciousness. It’s more fun and less serious, but it comes and goes. Jeremy’s [designs are] comical—certain things you can buy and really use, [and other] things are much more special and more expressive of an idea than they are practical.” Herein lies the greatest divide between Jeremy Scott and Gerlan Jeans collections; whereas Scott goes for shock and camp that’s beyond the wearability of an average person (i.e. not Katy Perry), Marcel wants her Gerlan Jeans to live on any body, in any context.

As she describes it, Marcel spent a good portion of her early twenties as a “professional student/Dead Head,” itinerantly attending schools like Hampshire College, a short-term art program in Paros, Greece, as well as a stint at Oregon College of Art & Craft before attending fashion school at Central Saint Martins in London. “When I was at Hampshire, I was still on the Grateful Dead tour. We were going to shows in California and then driving back and going to class on Monday, if we made it. But after Jerry Garcia died, I didn’t really know what I was doing.” It wasn’t until she was 25 that her long strange trip culminated in the Print for Fashion course taught by Natalie Gibson at Saint Martins, where she really learned to hand draw and develop a creative concept from an organic place. But even as she continues to hone her craft and create her own, rich worlds, it seems, at heart, Marcel has never lost that same wide-eyed spirit of being a super fan—a tireless champion of her scene. In all of Gerlan Jeans clothes there’s a touch of that posi, psychedelic hippy vibe tempered by a trained, sophisticated eye. She’s deeply influenced by the style of her musical world, which surrounds Fade to Mind labelmates Kingdom and Nguzunguzu, as well as Fatima Al Qadiri and Venus X. While this loosely-affiliated group of electronic producers couldn’t be more sonically different than the rambling jams of the Dead, they have attracted similarly fervent fans.

Like the aesthetic sensibility of Marcel and her cohorts, this music scene is also deeply influenced by internet-bred sampling and hip-hop production techniques, an artful pastiche of nostalgic noises that feed the look and feel of their subculture through online file sharing, YouTube benders and message boards, in mind, and late night at the clubs, in body. “I do get this palpable sense, just being around my friends and people in the city right now, that there’s really exciting stuff happening and there’s a change happening,” says Marcel. “I feel like I’m actually experiencing it as it’s happening. GHE20 G0TH1K, Venus X, and Kingdom, these really are new sounds. It’s a totally new thing, and it’s challenging people.” Marcel’s tendency to idealize the fashion and art scene in the late ’80s and early ’90s is due to the fact that it’s largely cosigned by a similar aesthetic, sound and mentality. She cites people like Patrick Kelly and his groundbreaking prêt-à-porter line in Paris and Lady Miss Kier, the former textile designer/Deee-Lite singer, and the painter Kenny Scharf, both of whom came out of the rich interdisciplinary New York art scene and who continue to be a source for inspiration and encouragement for the new downtown set. “They’ve been really supportive of all these kids who basically had their lives changed and get to do what they do because of [them], and [in turn, they] are experiencing a renaissance at the same time the generation they helped inspire are creating a renaissance. So it’s this powerful moment.”

In her autobiography D.V., longtime fashion editor Diana Vreeland offers a truism that Marcel would surely agree with, that “one’s period is when one is very young.” Like Vreeland, Marcel is able to match her overwhelmingly nostalgic character with a deep enthusiasm for the present. She’s keeping the dream alive. “When I was a tween and a teen, I went through various stages, but when I went through my alternative stages, Esprit and Benetton were so important to me. The “‘Mall Witch’” collection started out with me asking people at parties, ‘Can you pinpoint the time when you realized you wanted to be alternative?’” For Marcel it’s about basic joys, big personality and the comfort of feeling like you’re a part of something larger than yourself. In that way, the far-out wackiness of her prints and jeans serve more as a huge, enthusiastic thumbs-up smiley face stamp of approval for being different.

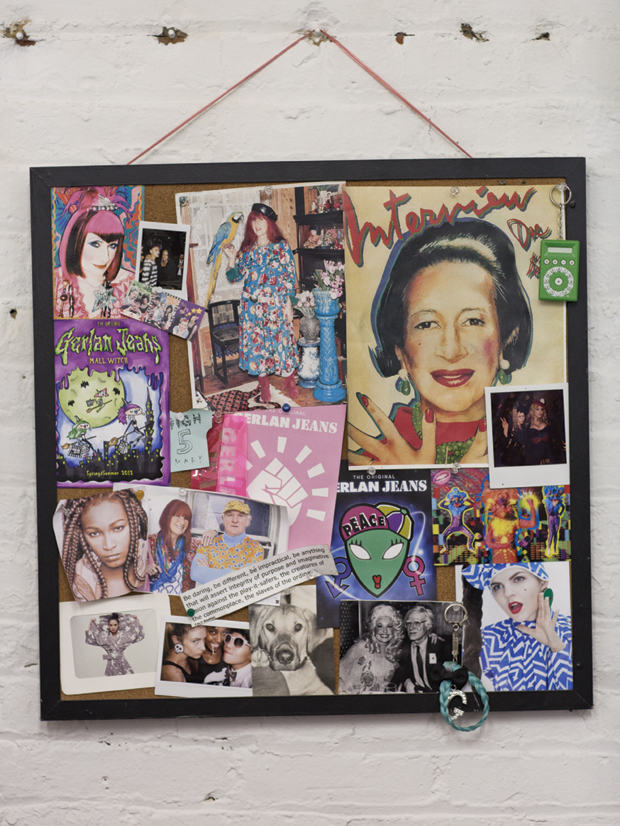

Back at the photo shoot, as Marcel helps a sylph-like model shimmy into her slime-green “wedding dress” piece, she jokes that bits of glue (which help adhere the dress to varying-sized busts) are not actually meant to be part of the overall look, and then takes a turn towards the serious. “When you put a body into [a garment], and that person is expressing it from their point of view, to me, that’s when the most powerful moment [happens]. To have that person on the street bring it to life in their own way and add their own energy. That’s the bottom line of why I do what I do.” It’s a little window into her work as a designer, and the challenges she faces in a world that seems to value less and less the art of fashion and instead is a slave to it, season-by-ever-churning season. On an inspirational cork board, sandwiched somewhere between personal photos, pictures of all her heroes—Mrs. Vreeland, Natalie Gibson, Dolly Parton and Betsey Johnson, among others—and an illustration of a power fist, Marcel’s pinned a fortune cookie-like slip of paper with a typed quote from Cecil Beaton, that reads:

Be daring, be different, be impractical, be anything that will assert integrity of purpose and imaginative vision against the play-it-safers, the creatures of the commonplace, the slaves of the ordinary.

Marcel is so far from commonplace, it’s almost easy to overlook the quality of her output. But it’s worth a second look. All one has to do is scan her studio to know that textiles are her passion and her extraordinary gift. Industrial shelves are stacked high with piles of exuberantly printed yardage—country patchwork-printed denims, pastel leopard print, black-and-white flamingo patterns, a carnival-sized teddy bear made of denim. Each stands as evidence that her commitment to the craft is never at the sake of humor. Her taste is a bit bold and brash—tacky, even—but never unconsidered, like a Tumblr whose every post has been hand painted. “I’m obsessed with that Andre Walker quote from MTV’s House of Style where he was like, ‘Tomorrow is going to be even grosser than today,’” says Marcel, eyes shining gleefully. “I love grossness, but grossness with an eye for sophistication.”