The inauspicious nerve center for Los Angeles’ most promising hip-hop movement is the back room of a residential home at the end of a cul-de-sac in a reasonably idyllic neighborhood in the city of Carson. The dimly lit studio space leaves just enough room for a tattered couch, a vocal booth and a Pro Tools rig. It’s here that the roster of Top Dawg Entertainment—Kendrick Lamar, Jay Rock, Ab-Soul and Schoolboy Q, collectively known as Black Hippy—first met seven years ago. And it’s here that they’ve stayed. “We’ve just been in the studio since, that same studio,” says Lamar. “Perfecting the craft.”

Craft is not a word his circle throws around lightly. On a mild winter night Jay Rock sits transfixed by the dual glow of his phone and a studio monitor. He’s playing the same beat repeatedly, writing and rewriting in his iPhone notepad, mumbling rhymes to himself in the process. Behind him, Ab-Soul sits unassumingly on a torn up couch, accompanied by a lady friend. He’s just zoning out, his bushy afro pulled back behind a pair of big black Eazy E-type Loc sunglasses. When Lamar arrives, with carryout teriyaki chicken in tow, he greets everyone with little more than a simple, distant pound and then makes an immediate beeline to where Rock is sitting. He dines and vibes, bobbing his head with a focused calm, alternately staring down the monitor and the rapper behind it, as if to form a psychic connection with whatever it is that Rock is building.

Schoolboy Q is nowhere to be found this evening, but his presence is felt nonetheless. When someone throws on his “Niggahs Already Know,” a minor anthem from his Habits & Contradictions LP, on laptop speakers, the seriousness of the room immediately cracks. Ab-Soul jumps up from his semi-comatose couch state and breaks into a set of loose, upper-body dance moves as the small assemblage of TDE artists and associates cheers him on half-jokingly. All the while, Jay Rock stays the course, playing that same damn beat, only breaking away from his digital notepad periodically to pull Lamar or TDE president/general manager Dave Free to the side to mutter rhymes in their ears in exchange for a nod of approval. After about two hours of this, Rock finally hops into the darkened vocal booth, where that whisper immediately turns into a growl as his trapped-in-the-hood lament comes to life. He blacks out, so to speak, perpetually lunging forward as he raps as if he’s about to jump out of his own skin. And then he does another take.

The next day, eating with the other three Black Hippies at a Korean fast-food chain a scant mile from their home base, Rock speaks of his dedication. At 26, he is the eldest of the posse, as well as its earliest initiate. A product of Watts’ decidedly Blood-leaning Nickerson Gardens housing projects, his earliest music is blindingly gang affiliated. 2007’s “Blood Niggaz” is a simplistic and single-minded banging anthem: I’m a Blood nigga when you see me better give it up/ Nothin’ but a B thang homie we don’t give a fuck. On last year’s Follow Me Home LP he sounds like a changed man, still tied to his affiliations but considerably more thoughtful and eloquent about them, In a matter of a second nothing matters when you reppin’ for your turf…it’s a sickness when you kill your own kind. He credits fellow Nickerson citizen, TDE’s founder and namesake Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith, with pointing him in this new direction. “I was one of those young cats and knuckleheads that was hard headed, that didn’t listen,” he explains. “[Top Dawg] locked me up in the studio and I’ve been there ever since.”

It’s Top Dawg who penned the five-point plan that hangs on the studio wall. Modeled loosely around 50 Cent’s rise to success, the poster board details the core traits necessary to become a rap star: Charisma, Substance, Lyrics, Uniqueness and Work Ethic. Rock distills this model to an even simpler motto: “Just make good music.”

This approach might seem antithetical in an era when entire rap careers are built on viral videos and short bursts of blog buzz, but it’s working. Each TDE release is like a clinic on how to produce rap music. Alone or together, their song concepts are fully baked, their intonations are highly energetic, their cadences extend and recoil organically. Where their contemporaries prioritize attitude and surface aesthetics, they focus on virtuosity and structure. In short, they just know well enough to try and the effort is reflected in their growing fan base. As Ab-Soul, emerging from his perpetual pothead haze, puts it, “If you make a good cake it doesn’t matter where you put it or what you put it in, somebody gonna eat it.”

Soul often speaks in such colloquial wisdoms. He was raised in Carson as the child (and later, a clerk) of a minor Los Angeles record store empire—after 30 years, his grandfather shuttered Magic Disc Music in Carson last year, and his uncle just announced the same fate for his V.I.P. Records in Long Beach (where Snoop Dogg recorded his first demo and can be seen rapping on the rooftop in the “What’s My Name?” video). As a rapper, Soul comes from the lyrical side of the hip-hop spectrum, citing late-’90s thesaurus abuser Canibus as an early influence and online message board text battles as his training ground. These days he operates with a distant cool that places him on a slightly different energy level than the rest of the collective. He’s both the crew’s sage observer and, frequently, the butt of its jokes.

“Soul know he’s the mascot,” says Lamar. “When I first met [him] I thought he was a nerd. A nerdy, wizardish genius. But it was another side of him that I saw an hour later when I went outside and he had two Black & Milds in his mouth.” If Black Hippy were siblings (and they basically are) Soul would undoubtedly be the baby brother. Though, when presented with this comparison, he’s quick to point out that he’s actually a few months older than Lamar.

“They’re all from the hood and I’m from the suburbs so I’m kind of an outcast,” Soul explains. “They give me a lot of problems like I’m not down.” As if on cue, Schoolboy Q responds from the other side of the table: “…gay ass dog doing an interview!” The heckling continues, with Q eventually chiming in: “You look like a black girl’s pearl tongue.” Soul struggles to get a word in edgewise, eventually trying to reason his way out of this allegation by deconstructing the genital slang. “Pearl tongue… Explain that to me. The pearl has a tongue?” After light debate about what pearl goes in which tongue, Q abruptly abandons the anatomical considerations. “You look like a squirrel’s ass,” he says.

Both a one-time community college football player and a Hoover Crip, Q’s story mirrors Jay Rock’s to a degree—he too was half forcibly pulled from a street by the TDE machine—but his demeanor couldn’t be more different. He’s the shit-talking cutup of the crew and the only member who insists on putting traditional utensils to use (“real Gs use chopsticks”). Naturally, he was the final convert to the TDE studio rat lifestyle. “He was just fucking around with it at first,” recalls Lamar. “He would walk in the studio with a big-ass 40 bottle like, Oh y’all doing music, huh? Let me do a 16 real quick.”

“[Black Hippy] was actually my idea because I was slacking in my music,” adds Q. “I figured if I could be in a group I could just write one verse and I could be good.” He admits to being intimidated when he first started coming to the studio but eventually the tenacity of his collaborators rubbed off on him. Now he raps effortlessly in elastic word blurs. And while he still habitually clowns everyone good-naturedly—On Lamar: “When I first heard Kendrick, I’m like this nigga a bitch, I don’t like this nigga”; on the possibility of a Black Hippy full length: “That shit ain’t never gonna come out.”—their collective pride in his rapid improvement runs deeply. So much so, that they unanimously anoint him the most talented rapper in the group. Q, of course, concurs.

This dynamic—a push and pull of props and hazings—fuels their recorded output as well. As a quartet, Black Hippy’s efforts are limited to a handful of playful posse cuts, but they tend to bleed through one another’s solo tracklistings. Sometimes they turn up for just a few bars before passing the mic off, but they’re always there, comfortable enough to know when to jump on a record and wise enough to know when to back off. “One thing about it when you in a group you gotta put your ego aside,” says Lamar. “Egos kill. Not only you but everybody around you.”

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth’s own ego is so aggressively muted that you might mistake him for anything else but a rapper. And yet the sleepy eyed, soft-spoken 24-year-old has become the unlikely breakout star of the collective, largely on account of the ideas bouncing around inside his head. Born and bred in the heart of Compton, his relationship with gang culture is a little more complex than the binary line his fellow Hippies sit on. Lamar’s father was a member of Chicago’s infamous Gangster Disciples. When, prior to his birth, his family moved to LA, they failed to leave the street mentality behind.

“My uncles and all my cousins was doing it on a daily basis—shootouts, running in my momma house, trying to hide somewhere, selling dope,” Lamar remembers. “So for a while I thought that was how it was supposed to be, until I ventured out into other spaces and people didn’t know about what was going on where I was from.” As Lamar watched friends and family land in jail, he consciously pulled away from the street, thanks in part to nudges from his ever-present father. “The cats that’s in jail they never had father figures. I had one,” he explains. “He wasn’t perfect but he was there to pull me out and let me know when I’m about to bump my head.”

If Lamar doesn’t noticeably carry himself like a street dude, he definitely carries the weight of the streets on his shoulders. A cautious optimist, he speaks at length about matters like caring for the children of his incarcerated friends and how his ultimate goal is to make enough money to bring community centers back to Compton. He speaks with a blind earnestness that’s both naive and charming. Last year’s underground album Section.80 functioned on a similar wavelength, offering an inquisition on the state of his community and generation. And, unlike so many so-called conscious rappers before him, Lamar proved unafraid to leave some questions unanswered. It’s been some time since this type of positive leaning, socially aware rap has been central to the hip-hop conversation. Around the turn of the century the burgeoning backpack rap sect drew a hard line in the sand between themselves and just about everyone else in hip-hop—from the most abrasive of gangsta rappers to the most innocuous pop stars. This had the unintended, if not unexpected, effect of narrowing their audience to little more than just ageing nostalgists and liberal college students. They cordoned off their choir and proudly took to preaching.

Despite occasional overlap in subject matter with conscious rappers, Lamar (and Black Hippy writ large) have not found themselves with a niche audience. Though Section.80 is ostensibly speaking to one specific generational sliver, it ultimately transcends demographics. It’s a balancing act of sensitivity and aggression, of consideration and ignorance, of self-seriousness and jest. I’m not on the outside looking in, I’m not on the inside looking out, Lamar bellows on its outro, I’m in the dead fucking center, looking around.

His crossover appeal may be even simpler than that. Unlike many of the backpack-era rappers that came before him (thus named for their bookish predilection for constantly carrying knapsacks), Lamar is willing to sacrifice substance in the name of style. He showboats in a spastic double-time on “Rigormortis,” bouncing around syllables like, A suit and tie is suitable and usual in suicide/ CSI just might investigate this fucking parasite. While Lamar attributes this approach to the influence of early Jay-Z, it more closely resembles the flow obsession of critically loved but generally ignored mid-’90s, West Coast underground acts like Freestyle Fellowship and Souls of Mischief, which makes it all the more surprising that it’s connecting so well today. He’s proving that there might just be as much capital in classical rap styling as there is in vapid swagger. It’s certainly connecting amongst his peers—he’s been given formal stamps of approval from Compton rap heroes Dr. Dre and The Game, as well as Canadian superstar Drake, who lent Lamar a full two-and-a-half minute solo track on his platinum LP, Take Care.

Lamar’s technical proficiency also serves to compensate for his greatest weakness—those brief moments on Section.80 where his naked honesty and genuine idealism can sound preachy or downright corny, particularly to ears weaned on brash rap tropes. (“No Makeup,” for example, dissolves into a “You ain’t gotta get drunk to have fun!” refrain that could’ve come straight out of an after school special.) Lamar is willing to wear his flaws on his sleeve, though and expects that this candor will pay off in the long run. “The best thing is to let people know that you a human just like them,” he says. “I think that’s why a lot of motherfuckers fuck with me because the shit I put out on my music is me not knowing everything. It’s me trying to figure out the world just like you.”

Sometimes Lamar is so broad in this worldly inquisition that he himself gets lost in the story. He’s mostly tightlipped about plans for his proper debut, Good Kid In A Mad City, but hints at a more introspective project. It’s hard to imagine what exactly this personal narrative entails because, for the moment, he seems to have so deeply buried himself in his art and career. How do you tell your life story through music if music is your life? “Music…is literally all I think about,” he says almost apologetically. “I could be talking to my momma and be thinking about music. So sometimes you gotta take a few hours out the week to really focus on family and not be caught up in your lifestyle.”

Later that day he does just that, paying his mother a visit at her home, a single story with two bedrooms and what Lamar calls a “traditional Compton kitchen.” “You got your little white stove top, a refrigerator with a hundred magnets, like a hundred boxes of cereal and noodles.” “I didn’t know he was into music,” his mother says. “Coming up, when he was a baby, we partied a lot. He’d always go in his room and eat his little cereal, make a cup of noodles and stay out of our way. He never was in the party scene.” A large, ’80s-style integrated DJ rig, with two mics and speakers about five feet tall, sits in the living room, seemingly left over from those party days. The system would still be the room’s centerpiece had Lamar not gifted his mom with the enormous flatscreen that now devours the other side of the room. A second TV of similar size swallows her bedroom. Amidst the big screens crammed into small spaces, his mother continues, “He was my only child for six years, he was my baby. He was lonely but he put it all into writing.” Now Lamar is the eldest of four. His 12-year-old sister just shrugs when asked about her brother’s music career. She prefers the more party-oriented output of fellow Compton rapper YG.

Early the next morning Lamar is back in the studio waiting for the other Hippies before a photo shoot. Taking the opportunity to touch up some tracks, he operates as his own engineer, pressing record a few bars early and then sprint hopping back into the vocal booth to lay his own vocals. Produced by Drake affiliate T-Minus, the track sounds a lot like, well, a Drake song with its bluntly emotional fluttering synths. It’s a record that could fit in quite comfortably on current day rap radio and yet Lamar seems a little embarrassed to be playing it in mixed company, perhaps recalling the fourth law of Top’s manifesto: Uniqueness. He emphatically points out that the track is not intended for his forthcoming album. It is, instead, “some freelance shit.” Then he plays a different track, one that is decidedly Kendrick Lamar. It folds much of everything he’s been talking about the past few days—his father’s teachings, his view of the world from the dead fucking center, Compton kitchens with a hundred boxes of cereal—into song, wrapped and rapped in fast flows and ricocheting cartoon voices.

“The debut album is really gonna put everything on the platform about where I’m at now,” he says. “You’re always growing and Imma put that in every song. Imma put my weakness in song, Imma put my strengths. You’re gonna see me.”

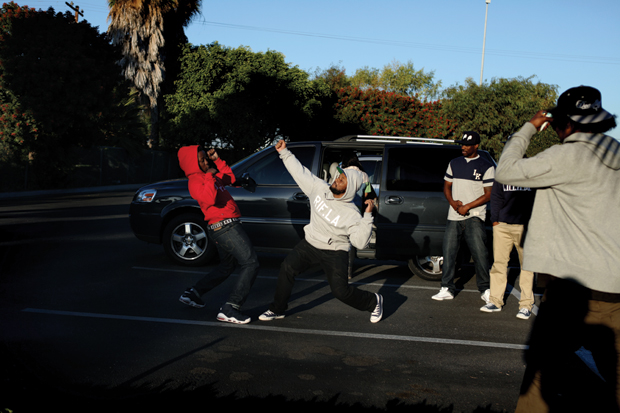

Soon the rest of the crew finds their way to the studio and the procession slowly moves outside. There is some confusion over where exactly the shoot will be taking place and a small caravan begins to spiral the cul-de-sac. As the TDE brass irons out the day’s plans, one of the cars blasts Q’s “Niggahs Already Know” and it once again sparks an impromptu party. Blunts are passed, bodies are slung into awkward half-dance steps and chants of the Niggas already know Q got… refrain so frequently work their way into the conversation that it begins to resemble a very loose rap cipher. This short burst of fun is both the reward for and the product of all of their hard work, the difference between being in the street and the studio may not be all that great.