Toronto’s Noah “40” Shebib is the one producer Drake can’t do without.

If you want a laugh, pull up the music video for Drake’s “Replacement Girl.” It’s 2007. The Toronto rapper is wearing a leather baseball cap, backwards, with enormous designer sunglasses and his necktie above the belly button—not unlike how Fred Flintstone does his. He double-time raps in front of a crudely drawn world map while women of various tint and confusion dance close by; at the video’s climax, Drake leans on the hood of an expensive car the director rented for the shoot. It’s not a bad R&B-cum-rap song. And the video went on to play on BET, a first for an unsigned Canadian rapper. But this Drake was, to put it kindly, not the cool, introspective, self-deprecating one we now know.

Something else happened at the “Replacement Girl” shoot. During a break, a wiry, white Toronto native named Noah Shebib showed up and played Drake ten beats. Shebib and Drake are both former child actors from the same hometown, but they were only meeting now, at the behest of a mutual friend. Drake didn’t buy any of Shebib’s beats that day, but he liked what he heard. He booked two days of studio time with Shebib at two hundred dollars a day, strictly to track new songs. Drake would rap, Shebib would hit record.

The session worked out better than either expected. By day three, Shebib told Drake he wasn’t going to charge him. Drake brought Shebib onto his team, first as an engineer and later as musical director for his live shows. As Shebib watched Drake going through the motions of the industry—listening to beats from top and up-and-coming producers that were never to the rapper’s full satisfaction—he slowly figured out, by process of elimination, what Drake really wanted in his music. “That was the first time as a producer I ever felt like I had a reason to do something,” Shebib says. “I wasn’t just sitting down to make music for no apparent reason.”

Working together now, Shebib and Drake first gave us the So Far Gone mixtape in 2009. The release reimagined R&B’s relationship with rap and what the two genres mixed together could sound like. Lyrically, it was deeply personal, quite different from Drake’s former bravado. Sonically, the hallmarks were eerie filtered synths, spare drumbeats, and lots and lots of space. Grammy nominations, Juno and ASCAP Awards followed their work for Drake’s official debut Thank Me Later in 2010, while “Best I Ever Had,” “Successful,” “Over,” “Fancy” and recently “Marvin’s Room” and “Headlines” have all spent time on Billboard charts, mostly at or near the top.

All of Drake’s music—every beat, every vocal take, every bite of studio banter—now goes through Shebib. He prefers not to work with other artists unless Drake is involved or approves. He doesn’t court the press, and rarely accompanies Drake on the road anymore. He’s a homebody; he’s also one of the most successful and emulated hit-makers in the business today. “That’s my brother,” Drake told me. “Within the realm of music, that’s the only person I’m related to.”

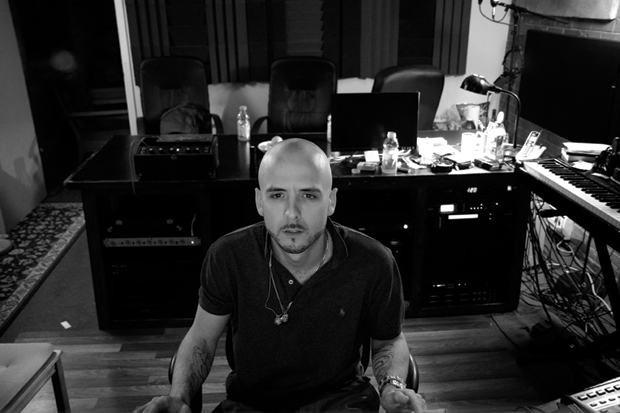

Shebib lives in a new, dormitory-like condominium complex in Toronto’s multiethnic Parkdale neighborhood. He is 28, slim but by no means brittle, with a clean-shaven head and a closely cropped beard. There is a large gold Rolex on his right wrist, and on his left is a bracelet of tiny saint portraits. Not one but two St. Christopher medallions are around his neck, and his grandfathers’ names, “Moses” and “Mavor,” are tattooed on his forearms. He has a slight scar over his left eye from a stint playing junior hockey. Put differently, Shebib looks not unlike what you’d expect a white guy from Canada who makes hip-hop records to look like. On the large, round, unfinished wooden table in his apartment, there is incense burning.

It’s after 6PM, but the producer’s been up only about an hour. As the delivery deadline nears for Take Care, Drake’s second LP due out October 24, the two of them have been working from nine at night to seven or eight in the morning. Shebib is a wake-and-baker, and rolls a long, meticulous joint at his table. ASCAP award plaques, including “Songwriter of the Year,” sit on the top of his kitchen cabinets—up high but not exactly eye level, as if Shebib still hasn’t decided how visible to make them.

Shebib loved R&B early on. “My favorite as a kid was DJ Clark Kent,” he says of the ’90s New York rap producer. “He would always have the illest R&B remix with a rapper on it. Those were always my favorite joints. Even as a kid, I’ve been trying to force-feed R&B to rap music. Make rap more musical.”

“Rap made more musical” is not a bad description of Shebib’s own aesthetic. Take a Drake song like the tired, wistful “Successful,” or the quietly menacing “I’m On One,” which 40 produced for DJ Khaled. The chords lead, not the rhythms, which is unusual for hip-hop. Shebib often favors closely voiced, four-chord loops, which create both a denseness and moodiness, more felt than heard. The synthesizer sounds he uses are built-in software pads that come with Pro Tools, but he manipulates them in peculiar ways: cutting out the higher frequencies so they sound muffled, like a churchly choir on “ooh.” Up until recently, you’d rarely hear a hi-hat sound on a Drake record—also unusual for the genre. Subtle moves like these let Drake’s voice sit almost literally atop the instrumental, but still sound connected to the music. “I let the center of attention be Drake,” Shebib says.

Another trick, which you can hear on Take Care’s “Dreams Money Can Buy,” is the way Shebib uses low-note synths to shake up an otherwise static hook. The song’s roomy vocal refrain, from Jai Paul’s “BTSTU,” is a naïve melody, something you’d see in a rudiments book. Shebib juices it with an ascending bass line, which gives the song its movement. When he incorporates beats from other people, like what happened with Boi-1da’s detuned horn fanfare for “Headlines,” Shebib performs EQ tricks to carve out space for Drake’s voice, beefs up the kick drum, does whatever it takes to make the beat more to Drake’s liking—or in this case to accentuate the indecision in Drake’s lyrics. In “Headlines,” the beat never fully drops.

Other times, Shebib just likes to break the rules. “Marvin’s Room,” in which Drake drunkenly lashes out on exes (and himself too), has massive dollops of sub-bass, which few home systems or iPod headphones can handle. An older Drake number like “Houstatlantavegas” has clashing harmonies all over the place, which Shebib left in “just for the sake of being an asshole.”

It’s uncommon for a producer who’s seen this kind of success to still track and mix every song. But Shebib thinks of himself primarily as an engineer, not a “producer.” There’s a potential arrogance to the term, and institutional confusion, since in hip-hop a producer is synonymous with “beatmaker.” Calling oneself an engineer denotes actual technical know-how, humility and professionalism. It means Shebib keeps his sessions running smoothly. No label people, friends, girlfriends, groupies or anybody else is allowed to hang around when he and Drake are at work. “I have to protect Drake from his own niceness,” Shebib says.

At Butler’s Pantry, a small ethnic comfort food restaurant on a main drag in Parkdale, Shebib hints at why he’s so uninterested in making a bigger name for himself as an artist. For one, he’s been immersed in showbiz since birth. His grandfather was (among many things) a three-time Peabody winner for his work in radio, and his great-grandmother was so influential in Canadian theater that the country named its version of the Tonys after her: The Dora Mavor Moore Awards. His father, Donald Shebib, is the celebrated Canadian filmmaker behind 1970’s Goin’ Down The Road. His mother, Tedde Moore, is an actress who played the role of the teacher in the 1983 cult classic, A Christmas Story. “She’s got a big belly [in the movie] because it’s me,” Shebib says. “1983. I’m in that film.”

Surrounded by the television industry as a kid, Shebib wanted to be in the business. He got his big break at age ten, when he starred in The Mighty Jungle, a sitcom about a zoologist father and his family, whose house is half inside a rainforest and half inside a zoo. Several years later, he landed a role in the Sofia Coppola film The Virgin Suicides.

But stardom didn’t necessarily mean wealth. The entertainment industry, already a fickle beast, is vastly less lucrative in Canada than in the States. Shebib’s family never had a lot of money, he says. His portrait of the cold, capricious industry recalls Drake’s own as an actor on Degrassi: The Next Generation. After working on the show for eight years, Drake and his castmates showed up one day only to see they’d almost all been cut.

It’s the usual Child Actor Story from there. Shebib had a lot of independence early on—40’s mother, as Drake points out on “The Calm,” says, “Don’t ask permission, just ask forgiveness”—and he ran with a tough crowd. Shebib lost all his acting money by 18, he says, after he was robbed at gunpoint during a drug transaction. There was also a severe run-in with the law for bank fraud. Just as he hit rock bottom, a family doctor (“Dr. Dave”) swooped in and gave him five thousand dollars to get his life back together. He used the money to buy a Pro Tools rig and enroll in engineering school.

He soon landed an internship with Noel “Gadget” Campbell, the go-to producer for all things Toronto hip-hop related, and even netted himself a gold record for assisting with R&B songstress Divine Brown’s LP. Helping out on a project for the artist Jelleestone, Shebib earned the nickname “40/40” from the artist’s kids, who would see Shebib working on a mix when they went to sleep, and still be working when they awoke the next morning. “He works 40 days and 40 nights straight!” they said.

Then catastrophe struck again. At the age of 22, Shebib was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a chronic illness that destroys the nervous system. It took three-plus years to get back into a condition where he could move around like his former self. “I was walking slower than grandma for six months, then like grandma for six months,” he says. Six years after his initial diagnosis, he gives no sign of pain or trouble walking when moving around town that night, but the specter of the disease seems to haunt all proceedings. There is no known cure.

It’s not a stretch to connect the sudden turns of his health, and first-hand knowledge of an artist’s hard realities, to Shebib’s attitude toward the spotlight. His goals are modest: “If I can listen back to a project that I worked on and be like, Man I love this, I fucking love it, that’s all that matters to me,” he says. That, and he wants to make his city proud—something he mentions multiple times over dinner.

“It’s all fun right now but who’s to say it’s all going to be this good in a couple years?” Shebib asks. “I’m not banking on it. I come from a family with one of the most successful Canadian filmmakers in the history of cinema. Trust me, it’s not all that good at the end.”

But right now, of course, it’s very good. After dinner, Shebib drives down a dark alleyway, past the Nestlé chocolate factory, and parks behind what appears to be a residential building. Around the side, in what would be someone’s apartment, is Shebib’s studio. The control room is dark, with deep red Persian carpets and brick walls on both sides. Bass traps and bafflers are pasted TRON-like on the walls and ceilings to insulate the sound, but aside from that, this doesn’t look like your standard hitmaker studio: no vintage synthesizers, little to no expensive rack gear, no rare microphone collection. Past the control room is the vocal booth, which is even more scarcely lit. It’s less a booth and more like a small lounge, with a loveseat and two more keyboards. Around midnight, Drake shows up to start the night’s work on Take Care, but first he plunks down on the couch and talks about Shebib.

“I never really set out to be the biggest artist in the world,” he says. “All I wanted to do was make my city proud. Noah and I share that goal together.” Drake, who is wearing loose jeans and an oversized Towson University sweatshirt, speaks in such a way that you can almost feel him revising each sentence as he speaks it. “The way you hear something is not the way I hear it,” he says. “But for some reason, the way Noah hears things is the way I hear it.”

From his seat, Drake leans over to an unplugged Wurlitzer and presses down the keys in no apparent order, emitting faint rings from the keyboard’s reeds. 40’s instrumentals, he says, evoke a kind of emotion that feels really right for him to rap and sing about. It gets him in a very personal and introspective headspace. Shebib knows Drake’s “sweet chords” and “sweet notes.” And Drake feels comfortable taking chances with his singing because he knows 40 will always make him sound good. So much of their music is born of late-night improvisation, and a kind of unguarded silliness you can only tap into when you feel truly one hundred percent at ease with another person. Many Drake songs, more than you’d think, are first takes.

The story behind “The Calm,” from 2009’s So Far Gone, speaks to the comfort zone they’ve created. At the time, Drake was living partially at Shebib’s bedroom studio. “I would be there every night and I hated going home,” he says. “I was deep in debt with my family. We were fighting every night. I had spent a lot of money at trying to succeed at music with these poppy songs like ‘Replacement Girl.’ Trying to be famous and trying to do it with a hit. I remember I had this vicious fight with my uncle on 40’s balcony. I had never said such cruel things to anybody; I had never had such cruel things said to me, especially by a family member. 40 could tell I just needed to say something about it. He made me this beat. I wrote the first verse in his bedroom, which is where we used to work. He gave me an opportunity to vent about my serious family situations. That was a definitive moment in my career. That was the first time I had ever said anything like that.”

Shebib interrupts us on the talkback monitor. “You guys have been back there a long time,” he says. “I’m worried what you’re saying back there.”

Back in the control room, there’s a pillowy mid-tempo beat on loop, with muffled drum sounds and a whale-like synth bassline that Shebib is improvising on a small keyboard. It’s a two-track instrumental from December 2009, which Drake had asked Shebib to try to find. The night before, Drake received a call from Andre 3000, who said he wanted to get on the rapper’s next LP—and, specifically, on a beat made by 40. The original name of the instrumental was “Good Enough for the Both of Us.”

“What a shitty title!” Drake says.

Suddenly they switch to boardroom mode. Drake, 40, and Drake’s DJ, Future the Prince, discuss Andre 3000 in frank, mathematical terms: the timbre of his voice, the cadences he prefers. They recall his obscure “Walk it Out” freestyle and the run of features since then, and talk about how their instrumental could be modified to better suit Andre’s delivery. A little after three in the morning, Shebib begins the process of protecting Drake from his own niceness. His studio assistant leads me out of the control room, past the atrium where Drake’s lone security guard is watching a samurai movie. Out the front door, past a group of young Toronto teenagers hanging by the rear of the building—unaware of what’s happening just a few steps away from their home, let alone that it’s being done in their honor.