In mid-August, French president Nicolas Sarkozy and his government began deporting local Roma residents, or Gypsies as they are known, to Romania and Bulgaria and demolishing their camps in response to clashes between the itinerant group and French police. This policy continues despite resistance by the international community and high-level French officials. Much of the background can be read in here and here, but what is lacking in most reports of this growing humanitarian crisis is the human portrait of the Roma people.

In May 2004, The FADER published a photo essay by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert, culled from his many years of visiting the Roma of Sintesti, Romania. After the jump, see the photos from that issue along with many not published, and read the story that ran along with them.

THE SETTLERS

The vanishing, old world traditions of the Roma

Story Chioma Nnadi

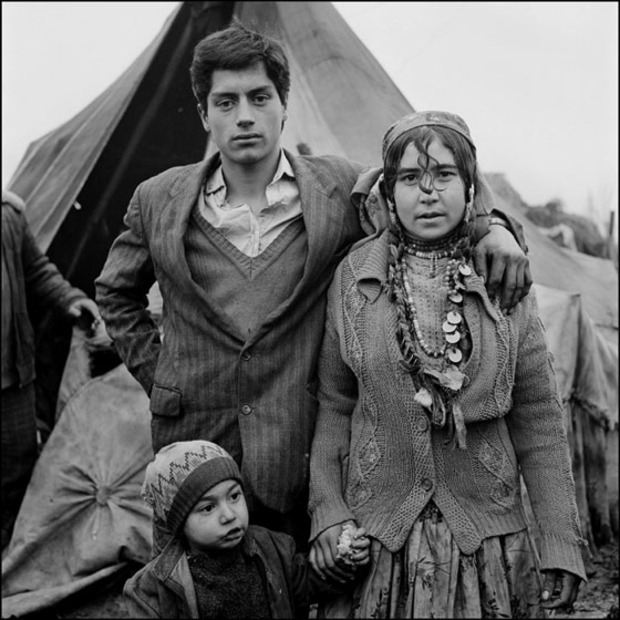

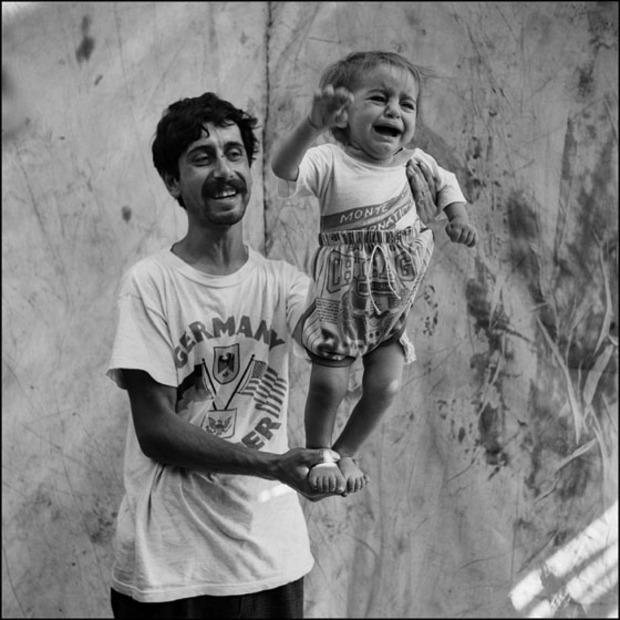

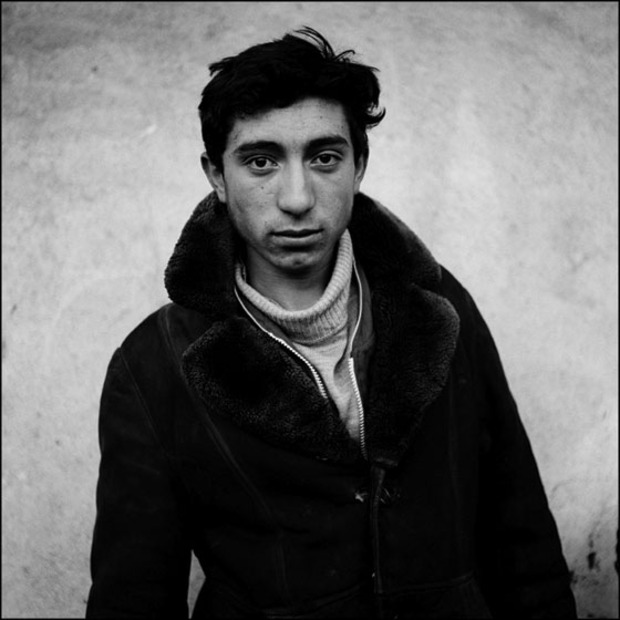

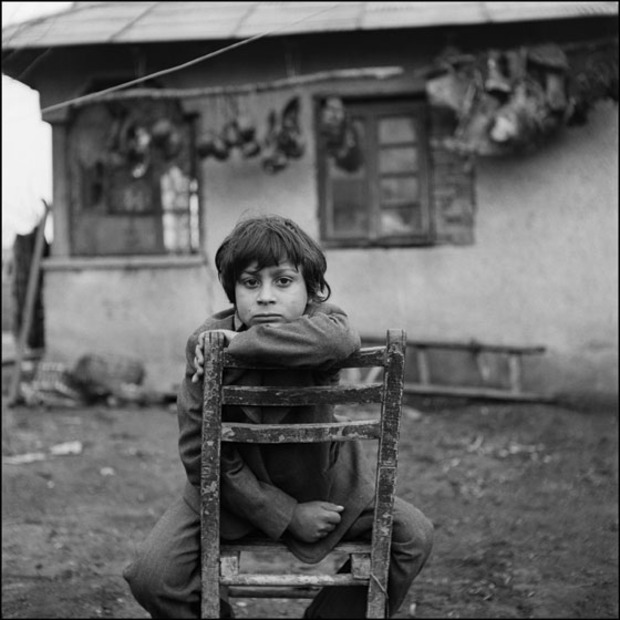

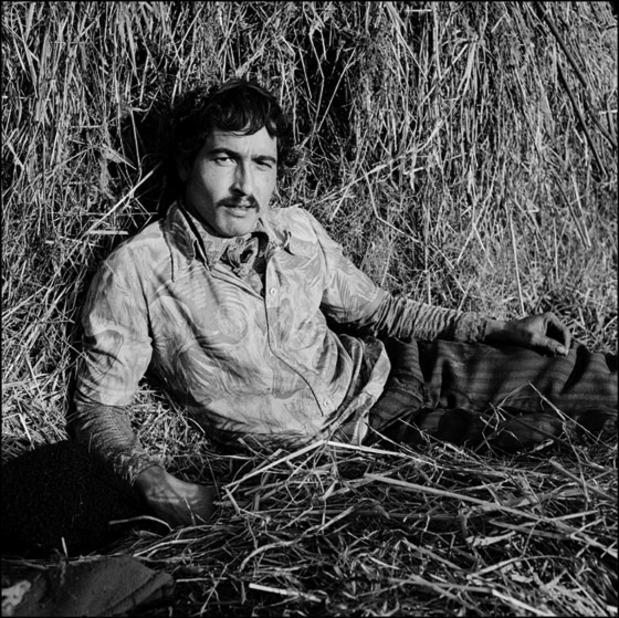

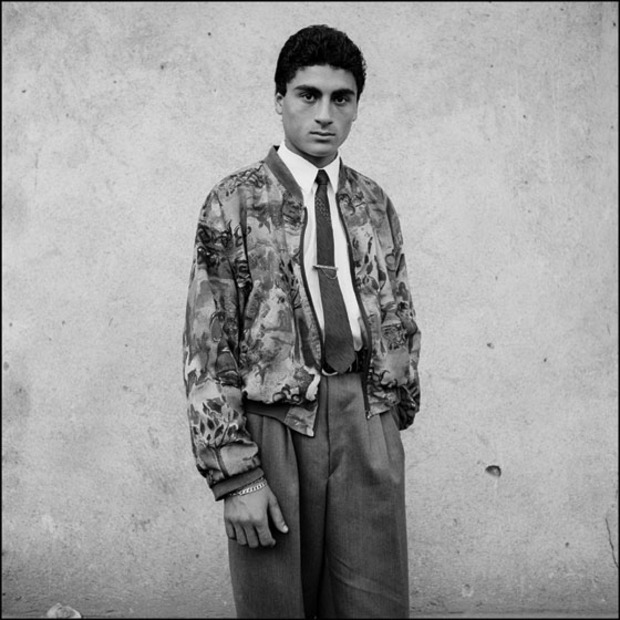

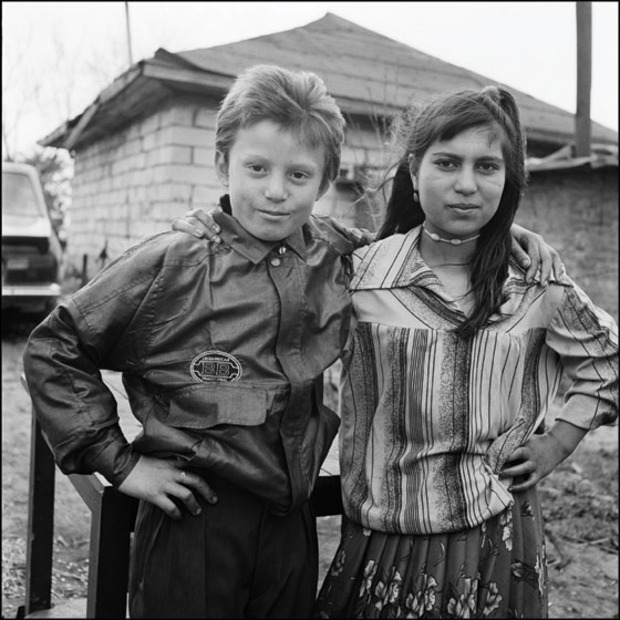

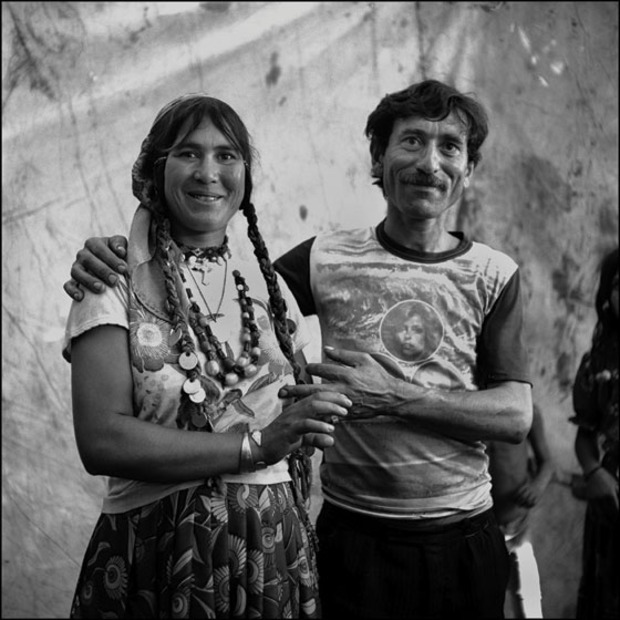

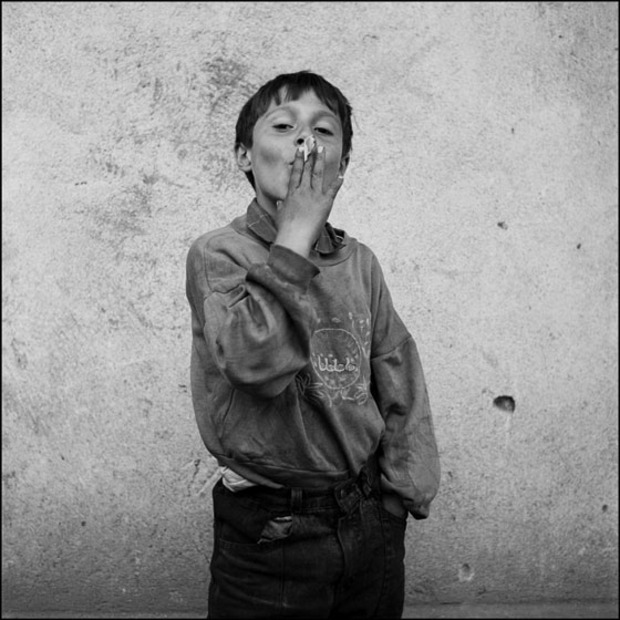

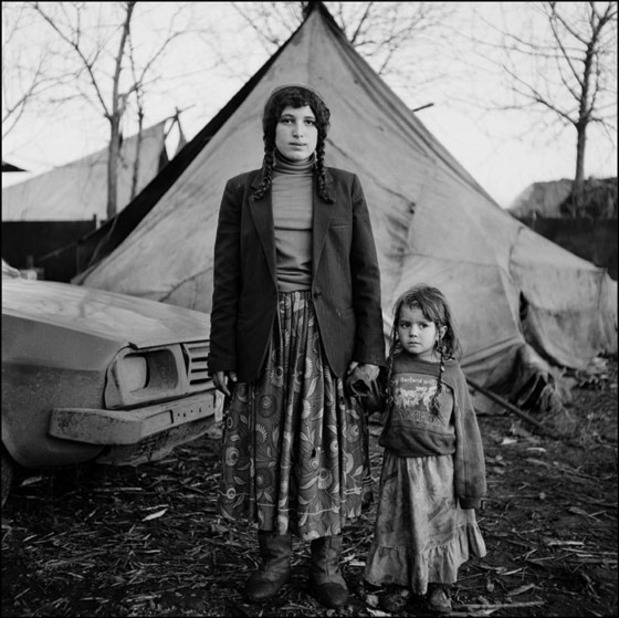

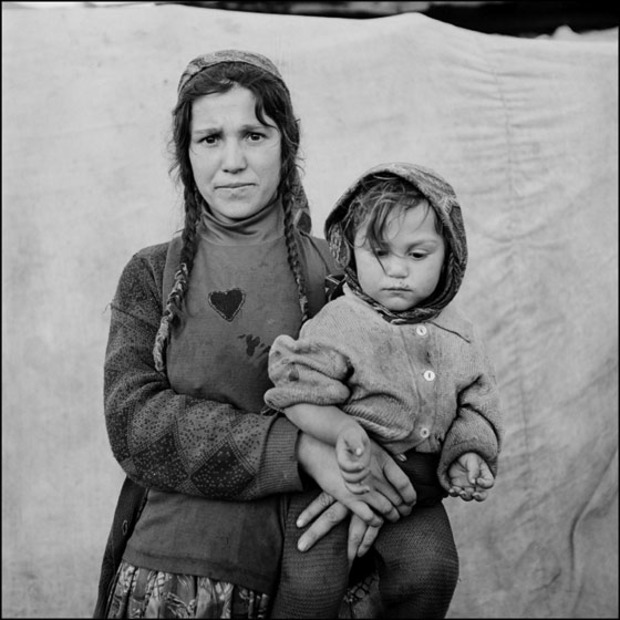

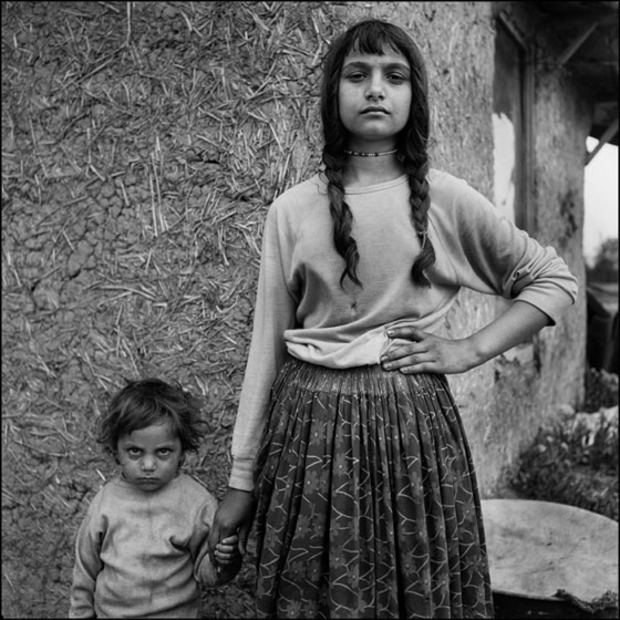

When photographer Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert came across the Romanian gypsy camp of Sintesti during the summer of 1990, it was as if he’d happened upon some fabled land that time forgot. Gathered outside traditional canvas tents were clusters of rosy-cheeked girls wearing gold coins for necklaces and men with untamed locks driving horse drawn carts. Although just a few months after the country’s revolution and barely a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this was a place seemingly untouched by the troubles of the ailing Eastern bloc. “I think initially I was probably very entranced with their look,” says Hibbert. “They seemed incredibly wild. Their gowns, their dogs and all these men coming out of tents with wild mustaches and wild hair—it was one hundred percent what you’d expect a gypsy camp to be.”

Hibbert went on to document the gypsies—the Roma, as they prefer to be known—for another five consecutive summers, gradually gaining their trust by distributing copies of his pictures, and eventually forging lifelong friendships with many of the families. Ostracized by the community at large, the Roma tend to keep the more intimate details of their culture a secret. Everything below the waist, for example, is considered unclean and untouchable—some families wash pants and skirts separately from their shirts and sweaters. It’s a patchwork belief system that borrows from religious and pagan traditions, a hybrid philosophy that’s reflected in their relationship to the outside world. While Elvis might be a popular name for young boys in the camp, many of the Roma have never heard of America.

After a ten-year hiatus, Hibbert returned to visit the camp, and what he found was a complete transformation. In a post-Communist economy, the Roma had become wealthy trading scrap metal, building oversized, gaudy mansions where their tents once stood, and flaunting designer labels and flashy cars. Today, palatial rooms with colorful murals and Italian marbled floors sit sterile with nothing but impressive executive bureaus and computers on show. “They have computers in their new houses but they just sit gathering dust,” he says. While these pictures were taken before the Roma acquired their wealth, there’s a great sense of pride and dignity in each gaze—Hibbert hopes to one day publish this body of work as a book. “The money hasn’t brought them happiness,” he adds. “Some of the elders in the camp wish things could go back to how they were. They say, ‘It’s no good living in a house, it’s not healthy.’ They prefer to sleep in their tents.”