In September, Legacy Recordings released To Be Free: The Nina Simone Story, a three-cd + dvd collection spanning the legendary singer's career, from her debut on Little Girl Blue to her final recordings on A Single Woman. The dvd makes available for the first time a 1970 documentary of Simone, which is excerpted in the video above.

The box set has since been nominated for a Grammy, so, to get the judges hyped and to give hints to our secret Santas, we are republishing segments of our own Nina Simone story from the FADER Number 38 Icon/Photo Issue. First, her daughter Simone speaks about growing up in and eventually growing out of her mother's shadow, and then, Nina's ex-husband Andy Stroud reveals some of the private moments that illustrated the singer's difficult brilliance. Read both after the jump along with photos from the issue.

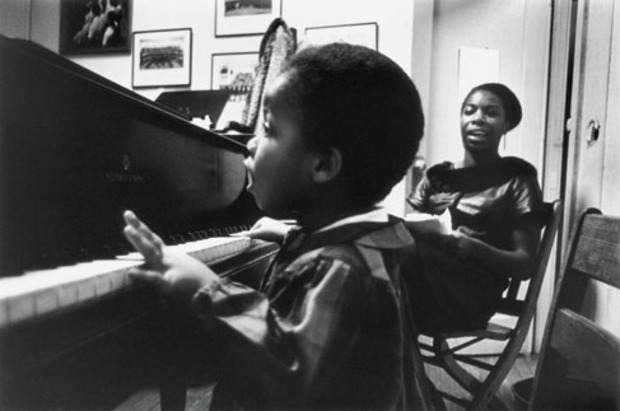

Simone: The Daughter

I remember her and my dad leaving a lot. For the first six years of my life I remember her being the softer one. She didn’t give me a spanking or anything like that, so she was my refuge and I wanted to be around her all the time. One fond memory is of my mother and father doing the jitterbug in the living room. You know how kids just love to see their parents together?

It was just a wonderful feeling to watch them in sync, laughing.

The people that I remember the most were Stokely Carmichael, Miriam Makeba, Betty Shabazz. Those are people I also had relationships with, those were my uncles and aunts. Times have changed a lot in terms of parent and child relationships. Children of divorced relationships weren’t really considered affected. It wasn’t talked about back then in the early ’70s, so I just remember one day my father was there and the next day he wasn’t. One day we were living in Mount Vernon and the next day we weren’t. No one explained anything to me and that’s still something that I have to work through. I wish that they had taken at least five minutes of their time just to say, Look, we love you, this is not because of you, we’re just not getting along, we’re just not going to stay together anymore. But that never happened.

Have you heard of Attilah Shabazz? She’s Malcolm X’s eldest daughter. Sometimes people tell me little stories about things I don’t remember and I’m able to put two and two together. She said that at one point her mom was trying to find my mother because I guess it was time for school to start and Betty didn’t know what mom wanted to do. I guess when Aunt Betty couldn’t find my mom she just put me in Montessori with her own children. I was maybe six, and every time the phone rang, I would say, “Is that my mommy?” And my father also told me later on that he didn’t know where I was. I guess he came home, the wedding ring was on the side of the bed and he didn’t know where she’d gone and he didn’t know where I was, so…

When I was 13 my mother and I got into a big argument because she wanted me to go to boarding school on the Ivory Coast and I just was not feeling that at all. I guess maybe I was just tired of moving. And then she somehow found a school in Switzerland, an international boarding school. Everything was fine, as long as she wasn’t around, and then she decided to come and turn my world upside down. The following year, I had a ticket to New York and we had a three day weekend, and I said to my mom, “You know what? I’m going back to New York to see my dad, and I’m gonna prove to him that he loves me like I’ve been telling you all these years. Or prove to myself that he doesn’t, like you’ve been telling me all these years. But either way we gonna get this straight.” I didn’t tell my father that I didn’t have a return ticket to Switzerland. So I landed on his doorstep, and of course he was happy to see me cause he thought I was only coming for three days, and on the fifth day, he was like, “Well, when are you going back?” And that’s when I had to tell him the real deal.

Make no mistake, the umbilical cord is stronger than logic. Throughout all of this, all I wanted was my mommy, her approval, her love, her support. It was very complicated, but the love was always there, up until the day she died. It’s just that you have to find a way to communicate with one another and respect one another. I could always reach her through music, there were a couple songs that she taught me that we could sing as a duet. I remember one time we were having a…she just…it was a lot of pregnant pauses, and I just started singing. She sat up straighter and she came in with the other part. Once we got done, it was as if that wall was gone. I was grown at that time; I realized at that moment, “Ah-ha!” I knew how to get through all the bullshit.

During the first few years of me making the decision [to pursue singing] and her really having a hard time digesting that and accepting it, she would ask me a lot of questions to try and see where my head was, and to also try to dissuade me. For every argument or every question she had, I had thought it out and I wasn’t afraid. At one point she said, “Well you know people are gonna compare you to me.” And I said, “That’s fine, I don’t have a problem with that, because I can guarantee you that at least 50 percent of them will not be disappointed with what they do hear.” And she’s like, “Well, they’re gonna expect you to play piano.” I’m like, “Well, I don’t.” And then she said, “Well, they’re gonna expect you to sing protest songs.” And I was like, “Well, I can sing your protest songs.” Basically she was saying, You’re gonna have to work really hard and you’re gonna have to bust your butt and you’re gonna be betrayed and you’re gonna be this and that. And I looked at her and I said, “And for any job or for anything you want to be successful at, tell me, which one do you not have to bust your butt at?” So after a while she just realized that it was futile. Then my mother finally saw me in Rent when I was Mimi on the first national tour. She loved it. She stopped questioning a lot of things and started asking me questions about my career.

One day in the early ’90s, I remember talking to a friend of mine about when my mom dies, and I was like, “I don’t want anything.” And he looked at me and he said, “Well, you’re her only child, you have no choice.” I remembered that being a real epiphanous moment for me. I’d been running away from the relationship, because it just seemed like I could never do anything right or couldn’t say anything right, and I just didn’t want any more of that pain. When I realized in that moment that no matter how far I ran I would never be away from it, I said, “You know what? Let’s see how she likes having a relationship with me.” I became more empowered in that moment, because then when I would deal with her, if she was having a bad day, I would say, “You know mom, I love you but I don’t think we need to talk right now. Call me when you’re feeling better.” She became aware of how I was feeling and it was up to her to either make the change, or not. I also think she started to respect me more, not only as a performer but as an individual—and was proud. So she was able, for lack of a better word, to relax. I know she had a lot of insecurity issues. She felt that I was competing with her. And I had to remind her, “Mommy, I’m not trying to take your place, I’m trying to be an extension of you, because you’re wonderful, and you have to know that you’re wonderful.” When my mother passed, for a while I grieved more for the fantasy that I was hoping for and that could never be. It was almost like, “How dare you pass away, before we reach the place that I want us to reach?”

I had a conversation with her three years ago in France, she was eating. She’d had cancer for a while, and she was in chemo and all that. I said, “What are you eating?” And she said, “Oh, some kind of grass,” because she hated eating salads and all that, she called it cow food. I asked her, “Have you lost any weight?” And she said, “Oh yeah, oh my God, I’ve lost a lot of weight.” And in that moment I knew that she was dying, because that’s what cancer does. And six weeks later she was gone.

Simone is the only child of Nina Simone and Andy Stroud. She is a singer and performer.

Andy Stroud: The Husband

I met Nina at the Round Table and we wound up later at the Drake for drinks. At the end of the night, she put a business card in my hand and on the back she had an inscription: “It was very nice to meet you—Nina,” with the date 3/7/61. We kept in touch and dated and it became hot and heavy. Nine months later we were married on December 4, 1961.

I found her to be a normal person at that time; I didn’t know what was underlying. Her moods varied a lot when I met her and she was going to the psychiatrist at least twice a week. I discontinued that. I told her, “Hey you’re not gonna have two men telling you what to do.” And she said, “Well, alright. But if you want me to discontinue seeing the psychiatrist, I want you to let him analyze you.” I said okay and went and he gave a good report: “Feet on the ground, square-headed. A nice guy, normal, no problems.” So she said, “Okay, you got a good report, I’ll discontinue.” And we also threw out the gays that were hanging around the apartment. There were some—mostly females—and I said, “We can’t continue this if we’re gonna be married.”

I put the relationship in five-year segments. The first five years were the romantic period. After she had the baby [Simone], she stayed at home for a while. We had the big house in Mount Vernon and we would sit in the dining room and evaluate each other’s potential. I was a lieutenant in the police department and she had this dream of being the first female black classical pianist in Carnegie Hall. We decided that I would get out of the police department and take over her career.

All sorts of people who became famous would visit us, young artists, Broadway people. Langston Hughes and Nina were great friends and they collaborated on the song “Backlash Blues”, which was one

of his poems. Jimmy Baldwin was there all the time, hanging out in the Village and the two of them would talk and argue and scream

and holler, but they were the best of friends. A couple of times Nina got into her nasty moods and didn’t want to go on stage—we had Langston, Jimmy, myself, all pleading, trying to get her on. Eventually, she would.

Nina and Lorraine Hansberry became friends. When she was rehearsing A Raisin In The Sun on Broadway, we used to attend the rehearsals and watch with Sydney Poitier and the rest of the cast. Nina and Lorraine became great friends, they had long discussions on world conditions, race relations, politics. All of these talks began to turn Nina into a devoted protester. Hansberry was a revolutionary—after talking with Lorraine for a couple days at her place up in Westchester, Nina would come home and she’d say, “Let’s go poison the water! Where’s the water supply?!” I’d go, “What the hell are you talking about?!”

She wrote her first protest song in 1964 as a result of the Medgar Evers killing, those three college students killed in Mississippi by the Klan and, ultimately, the four little girls in Alabama. That was the boiling point, she ranted and raved and stomped and ran around the house screaming, howling, sitting at the piano and pounding and came up with “Mississippi Goddam”. After a couple weeks of fuming, she got to the point where she just sat at the piano and I think she wrote that song in one or two hours—it just flowed out.

Nina was a very doting, very loving mother for the first three or four years, but as I say, I take it in five-year cycles. At the end of the fourth year or so she became occasionally despondent and depressed. She began writing letters saying, “Why did I have the baby?” and just questioning everything. At one time she was so concerned about these mood changes that we went to Columbia Presbysterian and she was there for three or four days. They ran every test known to science at the time, trying to pinpoint the reason for all of these mental problems and came up with zilch. Later on I heard in the ’80s —after I was no longer involved—they came up with some sort of brain chemistry imbalance and a certain type of medicine was recommended to stabilize her.

We officially divorced in 1972. We separated from January 31, 1969 until 1970, when we returned from the European tour. She ran off the plane and I didn’t see her for days or hear from her. We had an agreement: I paid child support, but not when the child was out of the country and I had no visitation rights.

No one wrote me [when she left]. I had no idea [where she was], at that time there were no letters, and she would call at two o’clock in the morning, complaining and wanting me to join her. Over the years, there were hundreds of letters of begging and pleading, which I never acknowledged or responded to, except in ’76. She had a situation in London with this African manager or associate who almost killed her, strangled her and left her unconscious. Subsequently, she attempted to commit suicide with sleeping pills, was taken to a hospital, revived. A few weeks later she was in an English countryside spa. I got letters and phone calls and everything begging me, and so I finally relented. I took a trip over and, after several days of talking, agreed to represent her in business action only, no personal relationships. So she came back to the United States and I got an apartment for her on Columbus Circle and she walked into the apartment and said, “This is a goddamn open grave.” I said, “Hey, what do you want? These are great accommodations to start, because we haven’t made any money.” She stayed for a while and then she ran off to Barbados.

CTI records wanted to record her at Philharmonic Hall and gave me expense money. Al Schackman and I went to Barbados to bring her back. We found her at a hotel on the beach, deeply in debt. Naturally she was very difficult to handle. We left and came back to New York and did the concert, but CTI went bankrupt and never recorded it. I had schedules, in ’78 and ’79, for concerts across the country. But it was the same old, same old. She had promised me that she would do the right thing, but she was the same old Nina Simone: bitchy, problematic, upset for no reason. You could never satisfy her.

In ’65, she started talking about suicide for the first time and it began to appear in later writings. She attempted it in London, and I think there was another incident, but she became very unstable at times, for no known reason. After her success in ’65, ’66 and ’67 she began to complain of being tired—we were only doing weekend concerts. [One time] I took out the schedule and counted, I said, “You did

30 concerts last year, how in the hell could you be tired?” We were living from concert-to-concert. She wanted to put a swimming pool in the patio, she was talking hundreds of thousands of dollars of refurbishment and upgrading on the house, but she didn’t want to work. I said, “Where are we gonna get the money?”

She always held me to account with a little bulletin board in the kitchen where I used to pin up notes like: “This time next year, you’ll be a rich black bitch.” She would get angry and say, “Look, you made this promise.” I said, “Yeah, but unless you wanna go out in the street and turn tricks, we got no money coming in. You gotta do mathematics.”

I was always trying to do what she wanted, but it was impossible. When she started writing protest songs, she would see Aretha and Nancy Wilson doing guest appearances and she would go into a frenzy, like, “Why ain’t I?!?” I said, “Nobody wants you! You can’t scream and holler about killing white people and think they’re going to have you as an entertainer.” I got her on the Johnny Carson show, and you’d think she’d sing “Porgy” or something like that, but she sang something that was totally unacceptable and a waste of time.

Harry Belafonte was one of the organizers when [Martin Luther] King had that Selma-to-Montgomery march. Belafonte called when we were at the Village Gate with Art Deluger, Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masakela. Belafonte called and said, “We’re having a celebration festival before they enter Montgomery.” When we got in, everybody was there: Hollywood people, all the black stars, and Nina sang “Mississippi Goddam”. She was in the front line, with her back to the stage, and facing the audience was Martin Luther King, Ralph Bunch and a lot of other well-known people. When she sang, that whole line got up and turned around to face the stage—she was a huge success. In those times, she didn’t show fear, she would get up and get involved and committed and she was ready to die.

Andy Stroud was married to Nina Simone from 1961 to 1970 and was her business manager throughout their union. He continues to release her recordings, and recently published a book of photos from their marriage.

It is available at www.ninasimone.biz.