Baton Rouge's best has a fresh-cut fade and a pepper-spray voice

From the magazine: ISSUE 53, April 2008

Connie Hatch, a 6th grade science teacher at Capital Middle School, pushes a limesicle-green Dodge Charger down the litter-strewn streets of South Baton Rouge. Chrome spinning in the dull February breeze, kids pedal their Huffys alongside, trying to catch a glimpse of their favorite neighborhood rap icon. Instead, they get a smile and a wave from Lil Boosie’s mom. “See how they act when they see Boosie’s car?” she says proudly, clutching the wheel at two and ten. “Tonight he has a concert at Southern University. It’s not that much money but he’s doing it because he wants to give something back to the children. I always tell him to give back to the community and stay humble.”

Listening to him rap, Lil Boosie sounds anything but humble. That voice—so shrill, so explosive—pepper-sprayed the airwaves last year with “Wipe Me Down,” a summer anthem convulsing with wild-eyed rhymes and scorched-earth synths. Sure, the original track belonged to Trill Entertainment labelmate Foxx, but it was Boosie’s sinus-rupturing cameo that pushed the remix across state lines and into the American popstream. Some were quick to associate him with the overnight success stories of Soulja Boy and fellow Louisiana yapper Hurricane Chris, but Boosie’s slog from the fringes to 106 & Park was long and hard-earned. Get your hands on the mixtapes he cut as a teenager, his voice strangely deeper than it is today. Listen to him rap about love, loss and trips to the hospital on his 2006 major label debut Bad Azz. Peep the gazillion YouTube clips of kids dancing to the viral thrills of “Do Tha Ratchet.” Or even better, drive around Baton Rouge with his mom and watch how children flock to his car at almost every single stoplight. Now, with another summer staring him down, Boosie isn’t flinching—he’s thriving in the grey area between hood respectability and ringtone contagion.

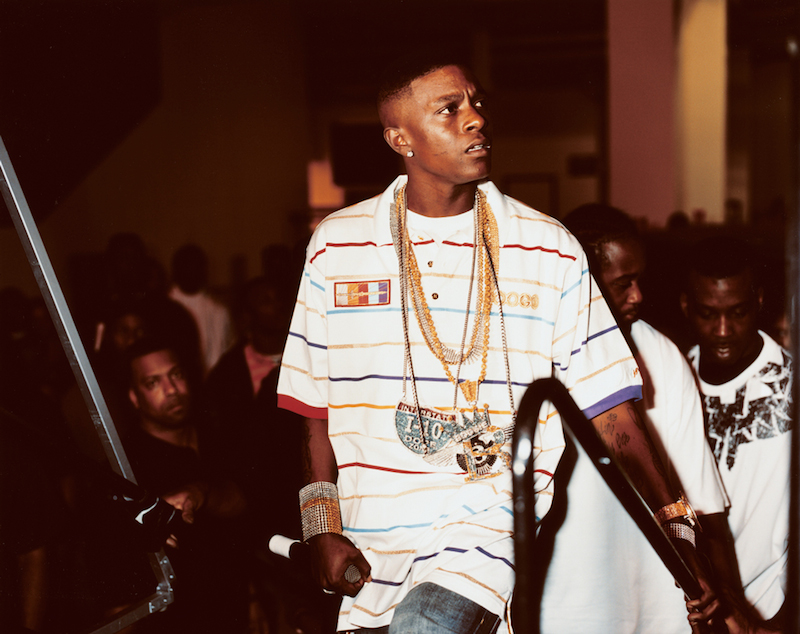

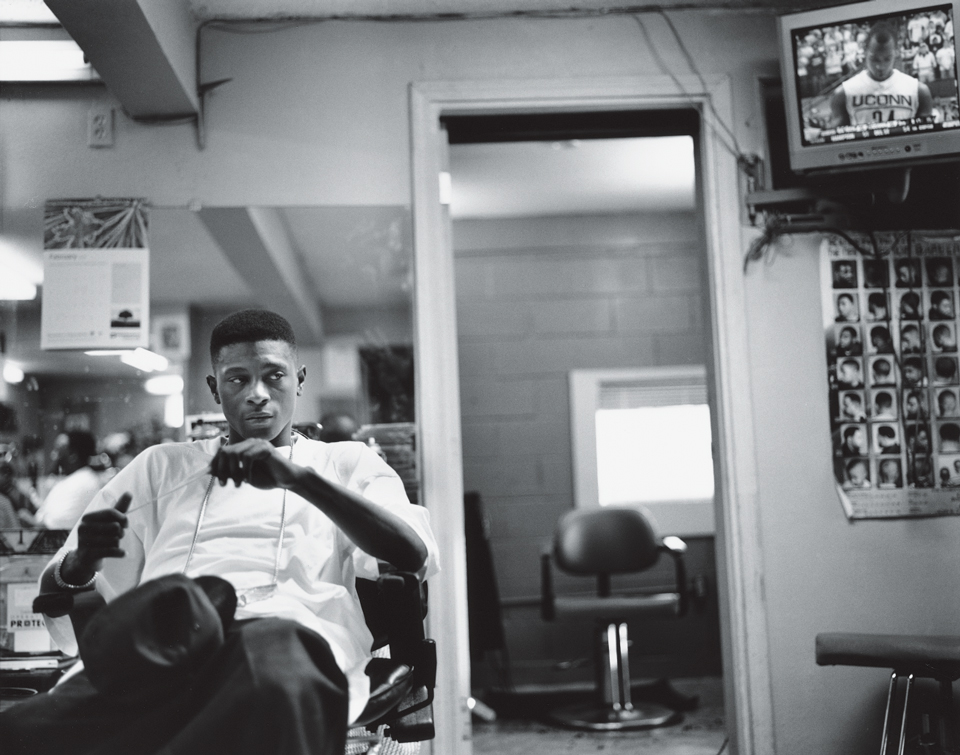

Pulling up to the Cortona Mall, Boosie’s mom parks the Charger halfway between Applebee’s and Firestone Tires. Her son is inside, rifling through racks of Coogi polos and SpongeBob-embroidered denim at a boutique called Man of Fashion. He emerges with half a dozen shopping bags dangling off his arm and navigates his way back to the parking lot where life transforms into an episode out of TMZ. Teenage girls surround him with camera phones, asking the rapper stop every ten steps to pose for a snapshot. “Eeek!” Click. “Thank youuuu!” Repeat. One starstruck young girl gets her picture taken, then dashes back to her mom’s Toyota in tears. By the time he’s reached his car he’s created a minor traffic jam outside of Macy’s. With his best friend Bleek, Boosie hops into a filthy Mercury Cougar (the car he drives around town to remain inconspicuous) and speeds off to the barbershop to tighten up his trademark fade—in a few hours he’ll be playing to the largest hometown crowd of his career.

Katrina’s fury barely touched Baton Rouge, but the city’s southside is still remarkably bleak. The neighborhood is nestled between downtown and the campus of LSU, a pocket of single-floor homes that look vulnerable to a thunderstorm, never mind a hurricane. It’s Election Day in Louisiana and a few lawns here are dotted with royal blue placards urging residents to “Vote Yes to Pinnacle.” It may be the presidential primary, but for South Baton Rouge this election is about a local proposal that would allow gaming corporation Pinnacle Entertainment to open a new casino within the city limits, potentially creating 1,200 new jobs in the process. If the President can’t save this neighborhood, maybe a casino will.

“I seen a lot of shit growin up, but, really, it was family-oriented in the hood,” Boosie says. “I was a regular bad ass kid, playing sports, rippin and runnin.” But when Boosie’s father died of cancer the loss sent the teenager into a new routine of misbehavior and missed curfews. “After his dad died he didn’t cry,” says Connie Hatch. “I sent him in for counseling because I thought something was wrong with him. That’s when the rapping started.” It didn’t take long for him to make a dent in the local scene. At 15 he was recording alongside hometown rap hero C-Loc, eventually generating enough buzz to catch the ears of Mel and Turk—two local entrepreneurs on the verge of launching a record label under the aegis of legendary UGK rapper Pimp C. Poised to replicate the Cash Money/No Limit model that had bloomed in neighboring New Orleans a few years prior, Trill Entertainment was born, giving Boosie a platform to unleash an avalanche of mixtapes and develop his petulant sneer along the way.

His status was rising in the regional rap world, but at age 20 Boosie was diagnosed with Type I diabetes. “I was in and out of the hospital so bad I thought God was trying to kill me,” he says. “I didn’t want to face that I had this shit. Then it just made me a dog. Diabetes made me a motherfuckin beast.” Boosie started taking three insulin shots day and rapping about it: Sick nights, need my medicine and my needles/ All the bondsmen, keepin it gutter with my peoples. Tempering his boasts with moments of raw vulnerability only deepened the loyalty of his hometown fanbase, and now no topic is off limits. “Whatever I feel uncomfortable about, I just say it,” Boosie explains. “A lot of people live by telling lies. I live by telling the truth.”

“I was in and out of the hospital so bad I thought god was trying to kill me. Then it just made me a dog. Diabetes made me a motherfuckin beast.”

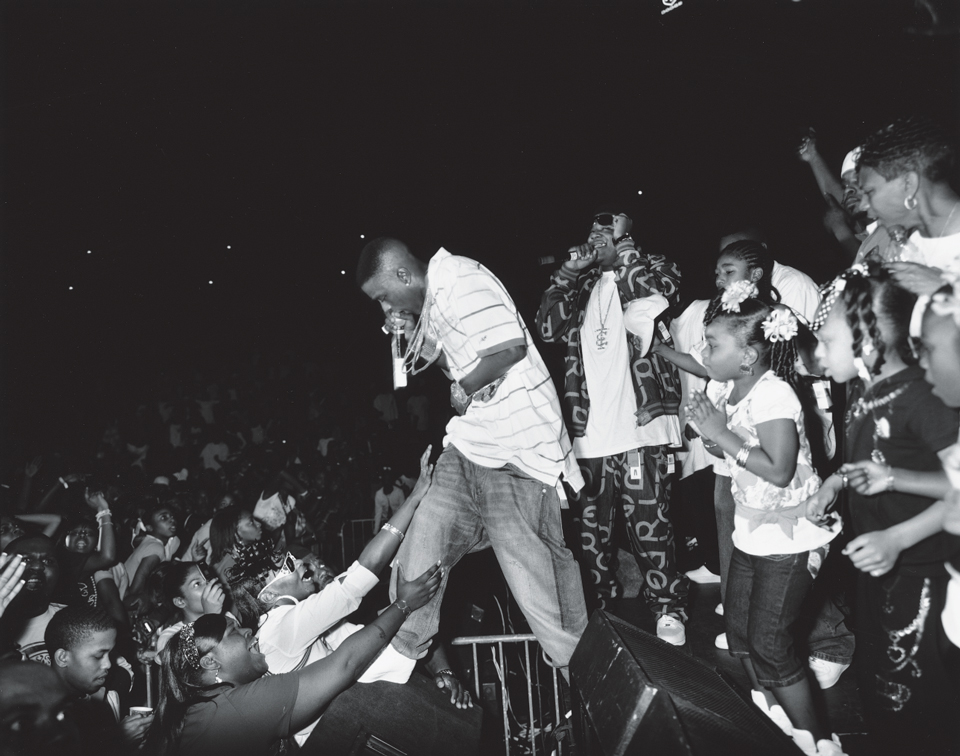

“B-O-O-S-I-E-B-A-D-A-Z-Z THAT’S ME!” 9,500 people scream along to Boosie’s verse from “Wipe Me Down” like it’s spelling bee rapture. With such manic energy pulsing through Southern University’s FG Clark Activity Center, it’s easy to forget that Boosie is actually the guest headliner of the annual Extreme Battle of the Bands, a family event that pits local high school marching troupes against one another in horn-to-horn combat. Teenagers too young to get into the club and children too young to know what the club even is have spent the past four hours listening to bleated versions of Sean Kingston’s “Beautiful Girls,” Shawty Lo’s “Dey Know” and other brass-friendly R&B jams, but as Boosie takes the stage, the young city salutes its hero with a wail.

Boosie does his best to work the packed stage, jockeying for room amidst his mother, his kids, his brother, his DJ, his uncle, his publicist, his road manager, his friends… Halfway through the set, he makes room for one more, inviting C-Loc up for “Outlaws,” the underground cut that introduced Boosie to Baton Rouge years ago. Little kids cling to the front row barricade and chant along with the pummeling refrain: Outlaws! Outlaws! Outlaws! And somehow, the energy keeps building. “Do Tha Ratchet” incites full-on contortionist dancing with a crew of marching band kids twirling their uniform jackets over their heads, and when the chorus of “Wipe Me Down” finally hits, everyone from the floor to the nosebleeds is reaching for their shoulders, chest, pants, shoes. Almost an hour into the performance, fights start to break out. (Boosie later says that his set lengths are rarely dictated by scheduling or money, but by how long it takes for his fans to start beating on each other.) As Boosie finishes his verse from the latest Webbie single, “Independent,” cops cuff a couple dudes and lead them to the nearest exit.

The show may be over, but the chaos isn’t. Outside in the parking lot, kids swarm the Trill motorcade, their cameras flashing uselessly against tinted windows. Suddenly, hundreds of teenagers charge in our direction as if fleeing from danger, then stop, turn and sprint back in the opposite way for no apparent reason. As cars trickle towards the exit, rumors of fights and gunfire travel across the parking lot—all of it unsubstantiated and probably just the result of thousands of adrenaline-loony kids waiting for their parents to pick them up from what may have been the best night of their lives.

Sunday morning brings balmy weather and victories for Obama, Huckabee and Pinnacle Entertainment. Off the I-12, 15 minutes east of Baton Rouge, sits Boosie’s new suburban home, a mini-mansion he moved into last summer. There’s a three-car garage with a spotless Bentley, a busted ping-pong table, an adorable new pitbull and puppy shit everywhere. Inside, a gigantic television screen illuminates an empty living room, while Boosie’s three kids dig through the kitchen freezer searching for popsicles. (They find them and offer me not one, but three.) Seated at the kitchen table, Boosie declares last night’s show the best performance he’s ever given in Baton Rouge, a statement that comes from a man whose recently been spending most of his nights onstage. “I’m out Thursday to Sunday, doing about three to four shows a week,” he says of his current schedule. “I’m not in the arenas, but I’m in that club, that underground scene, making after-party money, all that.”

“Whatever I feel uncomfortable about, I just say it. A lot of people live by telling lies. I live by telling the truth.”

The tour-centric approach is part by choice, part by necessity. Boosie’s albums have sold comparatively well, but with the music industry still sliding, rappers now have to chase dollars on the road. “People really wanna see you. People really wanna meet you. People really wanna listen to your music and see a real show,” Boosie says. “So if you ain’t got that, you’re just sitting at home waiting on a check every blue moon.” This new reality has started to affect his rhymes—sharp and piercing as if written to be heard through a muddy PA mix. Now with an album due this summer, Boosie hopes to transmute that live ferocity into another monster hit or two, spreading the hood superstardom he’s found in Baton Rouge across the country. “I don’t make one hit wonders,” he says defiantly. “I want people to go deep into my music like Baton Rouge does. This shit ain’t just bout bustin guns. My songs be about energy.”

To prove it, Boosie tromps upstairs to his home studio to play a couple tracks he plans to leak to the internet in the coming weeks. He opens ProTools, cues up a deafening epic called “Take the Pain Away,” and, as if unable to stop the syllables from ricocheting off his tongue, starts rapping along. Now here’s the crazy part: the decibels are pouring out of these studio monitors, enough sound to make my jeans shake, yet I can still hear Lil Boosie’s voice slicing through the din. It’s coming from his own mouth— too noxious, too insistent to be contained by a summer hit or by Baton Rouge itself.