In our 50th issue, Edwin "Stats" Houghton, our resident expert in all things diaspora, looked back at some of the moments and musics of our past coverage of the islands that changed the way we think about and cover other moments and musics all over the world. From FADER 23's Beenie and Tego cover story all the way up to FADER 49's Jah Cure feature, and many points before and hopefully after, these are the songs and clashes and movements that shifted popular music before it even knew what was happening. Check the essay and photos after the jump along with some of the videos we remember most fondly.

Story Edwin "Stats" Houghton

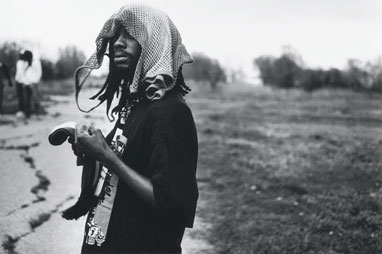

Photography Andrew Dosunmu

Tego Calderón was nowhere to be found and Beenie Man was out cold, nodding off in the back of a stretch Range Rover limo parked outside of Jammyland Records in the East Village at almost the exact moment that the tape started rolling. It was not an auspicious start for the cover story built around dancehall king Beenie—taking advantage of the Range’s roomy interior to sleep off a night of dub plates and soundbash cameos—and Calderón , at this instant in 2004, the closest thing Beenie had to a counterpart within the baby-step genre of reggaeton. Eventually Calderón arrived and Beenie regained consciousness—no sooner was he awake than he began holding forth about color-coordinated Clarks and Yellowman and Dave Chappelle. Which just goes to show that auspicious don’t mean shit: that meeting of minds and the photos that resulted are one of a handful of moments that have come to define this magazine. Although not the first publication to spotlight a reggae artist—or even Beenie Man, for that matter, who had already talked up his crossover chances in other magazines—F23 nonetheless captured a singularity. Chopping it up with Calderón about Spanish-speaking reggae fans who could sing every patois line of their favorite boom tune, it might just have been Beenie’s first chance to speak as an ambassador of his culture rather than an escapee from it, free from the weird expectations (Is he Bob Marley reincarnated? Can he water down his sound without losing his identity?) that usually haunt such stories. Calderón likewise had already been featured as an underdog champion of Puerto Rico’s reggaeton scene in F20 but happened to share the cover with Beenie just a few ticks before that cultural time-bomb propelled him and his peers onto mainstream radio.

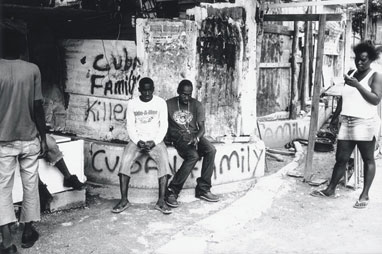

But this story—and hopefully, FADER—is not about media moments so much as it is about those other unmediated cultural moments that precede them. To really get it, you’d have to forward through the first stage of the mag’s development, watching it sprout out of the New York dirt as a bunch of Gotham-based DJs and hip-hop writers started to look outside the city for inspiration and just kept looking further and further afield until NYC and rap were no longer the only or even the main reference points. Even though Brand Jamaica exists in the mind of many as a reggae soundtrack that happens to have a country attached to it, the FADER’s first forays into the Caribbean basin were oddly focused on visual artifacts; gelatin silver prints of Rastas deep in the hills (“Yes Rasta,” F5), vintage Kodachromes from Rockers cinematographer Avrom Robinson (F12), and the infamous shot of Bob Marley which graced the cover of F10 with no cover story to back it up. You might also note that—counter to conventional media logic—clashes, soundsystems and dub plates were given the feature spotlight before any particular poster boy for the dancehall sound, or that well before the release of Calderón ’s hometown tribute “Loiza,” FADER was the type of magazine to just up and travel to PR on a mission to document the afro-rican street culture of Loiza Aldea (F17) simply for the sheer horizon-expanding fuck of it.

This open approach—call it deep coverage—provided a context for West Indian music that other media outlets lacked as they attempted to squeeze new stars into familiar boxes. It allowed The FADER to ride ahead of established portals for Caribbean music (like Hot97 and BBC 1xtra), with dancehall crossovers like Cham’s “Ghetto Story” (F36), Mavado’s “Weh Dem a Do” (F42), and Vegas’ “Hot Wuk” (F44), not to mention the global pop monster reggaeton became as “Gasolina” and Nina Sky conquered speakers from Spain to Bangladesh. Some have translated directly into measurable success stories and others will be filed as one-hit wonders, but these flashes of Caribbean spirit onto the collective consciousness signify something more profound than Soundscan numbers. In fact, maybe two things.

Primarily, The FADER’s West Indian love affair comes about in the era when bashment tunes bleed into reggaeton into cumbia dub into ragga soca, back into one drop in a unique circle of innovation. West Indian music has always jumped from island to island, salsa horns can sound like ska if you hear them just right, and first-world capitals like New York, London, Toronto and Miami have long been melting pots of consolidated pan-Caribbean identity. But now this transnational vibe is resonating not just in the barrios of cosmopolitan cities but in the transnational space itself, courtesy of chat boards, internet radio, YouTube. Notting Hill and Flatbush and Liberty City are not so much enclaves as islands more connected to the ghetto archipelago than to the boroughs next door, and they are populated with people who bounce from place to place along this chain almost as frequently as their data packets. Their musical representatives, half-caste royalty like Black Chiney Soundsystem (F43), Sean Paul (F23) and Collie Buddz (F47), should be recognized not as visitors overstaying their visas on an exchange program, but as forerunners of a whole new standard, a global market wherein traditional rappers and rock quartets may soon be the outsiders.

Secondly, if, within this emerging pan-Caribbean domain, Jamaican music has tended to be a blueprint of sorts, it is the grimiest, most warlike, least accessible qualities that have made it so and may ultimately have the greatest impact—even if they are still consigned to the underground for now. Dancehall is not just a genre but a technology, a black market economy and an ultimate fighting system in one. Even as riddim auteurs like Dave Kelly and Jeremy Harding attempt to transcend the overproduction and crabs-in-a-barrel competition of the 45 market with higher production values and selective releases, the mainstream market at the end of the crossover rainbow seems already to have been infected by the soundsystem model. Its future looks eerily like handheld video, clashes and yard-tapes as pop artists invent feuds to sell records and turn to internet and mixtape DJs for buzz. These days, even Ne-Yo and 50 Cent hope for rewinds, airhorns and bomb-a-drop sound effects to give their shit the proper shine when they release a new tune to radio.

In fact the most prophetic thing about that F23 cover story might have been the King Clash performance by Beenie Man and Tego Calderón , complete with robes and boxing ring, that followed, a gesture clearly in synch with Beenie’s vision for the future of dancehall, as laid out in the interview:

It never gonna go away from sound clash and soundsystem; it’s the biggest thing. You see, it’s a Jamaican motto to battle: fuck it. It’s like, “I don’t care how great you is, you have to battle,” and if you not battlin’ with nobody, then you nobody. Trust me, even the biggest of the biggest have to do it. Tony Matterhorn, Fire Links, all these people, they’re the kings of dancehall right now, they’re the king selectors in the business. Jammys is not playin’ sound no more, you’re not gonna see Inspector Willy inna dancehall. But their sons, and their sons after, is the ones that gonna keep the dancehall goin’. So clashes will always be in dancehall, always. I kill you, you kill me.

It may not sound like much of a motto for a New World Order and yet this ghetto celebrity death match mentality is precisely what makes soundsystem culture such a global model. Every DJ’s job is to be king and yet the massive is always ready for an upset, the dancehall hard-wired for permanent revolution. When the 90 BPM march of the pocoman jams is appropriated by reggaeton, it must be overturned in favor of soca-tempo dance. When bashment loses touch with reality on the ground, it must be slashed and burned like so much sugar-cane by “Welcome to Jamrock” and “Notorious.” These will be trumped by ’90s throwback, which will in turn give way to gun clappers by Mavado, Vybz Kartel or a resurgent Bounty Killer. The sound boy is dead. Long live the sound boy.

Damian Marley, "Welcome to Jamrock"

I-Wayne @ FADER CMJ Space

Baby Cham, "Ghetto Story"

Mavado, "Dreaming"

Tego Calderón f. Voltio, "Julito Maraña"

NORE f. Daddy Yankee, Big Mato, Gem Star & Nina Sky