Buy a print copy of the Blueface issue of The FADER, and order a poster of his cover here.

Blueface is resting his arms on a white marble table in a Beverly Hills boardroom. A Rolex cuffs the end of each sleeve on his black G-Star tracksuit: one has a blue time face and the other is solid gold. Surrounding him at the gigantic, U-shaped table is a team of talent agents. While the 22-year-old rapper sips a Sprite from a biodegradable cold cup, his manager, Wack 100, does most of the talking. “I’m in competition with everyone at this table,” Wack says. “I’m doing my part. I need you to do yours.”

The suited agents at the gilded table have a lot of ideas. Blueface would be perfect for a Hennessy sponsorship; he’d definitely go viral as the face of a Calvin Klein underwear campaign; has he thought about partnering with a brand to bring awareness to a cause? They’re getting hundreds of requests for him every day, they say, it just depends on what he wants to do. They’re confident they can get him a role in Fast & Furious 9.

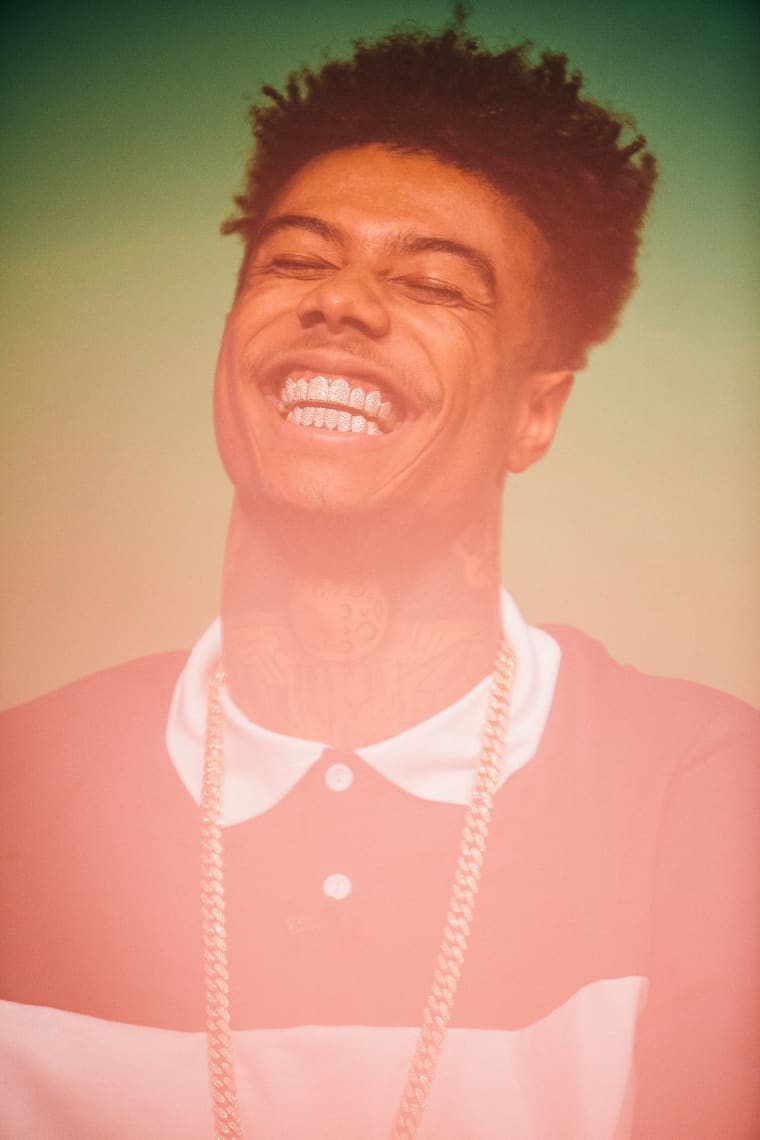

Every person in the room, and maybe Blueface more than anyone, thinks he has the potential to be a rap superstar. He looks the part: tall and slim, he still has the boyish good looks of the star quarterback he used to be. But his tattoos — most noticeably, the hundred-dollar bill version of Ben Franklin’s face on his right cheek — provide a bad boy edge. Over the past nine months, he’s become a polarizing phenomenon for his online persona as much as his music. For some, he’s the meme of the moment; for others, he’s become the latest stand-in scapegoat for hip-hop’s demise, his offbeat rhymes signaling the end of “real” lyricism as we know it; and still others simply enjoy the unapologetic arrogance and absurd lines in his songs.

After the meeting, in the backseat of Wack’s BMW, Blueface rubs Cortizone cream on his most recent tattoo: a small piece on his forearm of the orange SoundCloud logo. He uploaded his first song on the platform in September 2017, setting goals to hit for plays and likes before he would release anything new. “If I told you I had the blueprint, would you believe me?” he asks; it’s one of the first things he says to me. “From the first song I made to the song I recorded last week. When I started doing the music shit, it wasn’t like I was just winging it. Everything I did was calculated.”

“Deadlocs,” originally released in January 2018, was the song that racked up enough plays on SoundCloud for Blueface to decide to shoot his first music video. At the very beginning of the clip, before the song starts, he sits in the driver’s seat of a car, looking himself over in the rear-view mirror. “I’m on my Corbin Bleu shit,” he says to his reflection. “Just call me Corbin Blueface, lil baby.” Like much of his catalog, the song has the same scattered bounce as most contemporary West Coast rap. It’s Blueface’s performance that takes it from average to captivating; he jams quotable phrase after quotable phrase into each bar, using the beat only as a reference, his voice rising to a screechy pitch as he anticipates the reaction to what he’s about to say next.

“I don’t even like watching that video no more,” he says. “It’s annoying watching me act like that. It’s Blueface times ten. I always try to do me times ten ‘cause you ain’t got too much time to really get to know me.” It’s this self-aware yet out-of-pocket line that Blueface walks that’s both made him into a meme and kept him from becoming satire. In his songs, in his videos, and on his Instagram, it’s like he’s daring you not to take him seriously but laughing at your broke ass either way.

Blueface started playing football when he was 10 years old. His parents separated when he was very young and, for much of his life up until high school, he spent half the year living with his dad and the other half living with his mom. “The first trip I didn’t like it, but I got used to it,” he says. “It taught me a lot: how to adjust and adapt.” His dad moved around a lot — Santa Clarita, Anaheim, Oakland — and Blueface would stay with him during his football seasons. “I’d go to practice and go home,” he says. “I ain’t have no friends, I was anti-social. It was like, You know of me but you don’t know me. It’s still that way. I like it that way.”

On YouTube, there are multiple highlight compilations, under his real name Jonathan Porter, from his junior year playing quarterback at Arleta High School in the San Fernando Valley. The videos began circulating on social media in the wake of his rap fame, mostly because they’re really impressive: he can be seen tucking the ball and dodging linemen on long runs and throwing downfield bombs into the endzone with ease. With a lack of recruiting interest from colleges, Blueface acted on his mom’s idea to email his highlights to coaches himself. Fayetteville State University, a historically black college in North Carolina, gave him the best offer. “I had to go recruit to get recruited,” he says. “Just like I’m doing now.”

“That’s what this industry is based off of: a bunch of mouths moving, gums popping, no matter good or bad.” —Blueface

Before he ever rapped about having “two dicks in his pants,” Blueface had an Instagram account called The Fade Room, a play on the name of the popular gossip account The Shade Room. He was back in L.A. “being a barber, gangbanging, and selling drugs” after his stint in Fayetteville didn’t work out. (A coach decided to play the redshirted freshman in a game, ruining an entire season of his eligibility.) He had also grown homesick.

“Once football started going left it was like, Why am I here?” he says. “It was too different.” On the Fade Room account, which he estimates had 500,000 followers at its peak, he posted pictures of his haircutting skills and videos of him and friends boxing. “I was giving fades and we were running fades,” he says. “It was just something I did for fun. I didn’t even post pictures of myself. I wasn’t in that state of mind.”

Blueface made his first song purely by chance. After he drove TeeCee4800, a rapper from Mid-City and also Ty Dolla $ign’s cousin, to his show one night, TeeCee left his phone charger in Blueface’s car. TeeCee told him to pull up to the studio to get the charger back and he ended up sitting in on the session, where everyone in the room was writing to an instrumental. He beat everyone else to the booth. “Soon as I heard my voice…” he says, snapping his fingers.

His pivot to rapping coincided closely with the birth of his son, and he used this period as a stay-at-home dad to fine-tune his blueprint. “I would be at home with my son, write lyrics, rap on the Gram, come up with ideas,” he says. “When he get tired of me, I get tired of him, I had time to come up with shit.”

Listening to the rapper’s first few SoundCloud uploads, it’s clear that he was experimenting with his flow. For his biggest detractors, the main criticism of Blueface is that he can’t stay on beat to save his life. But on “Kicc A Doe,” the first song he released, he stays pretty close to the pocket for nearly three minutes. On his next song, “No Relations,” he tries his hand at Chief Keef-style melody. It isn’t until “Assistant,” the song that chronologically precedes “Deadlocs,” that he starts to really color outside the lines. His flow isn’t completely original; listeners have pointed to rhythmic pioneers E-40, Suga Free, and Silkk The Shocker, as well as more contemporary examples like Pablo Skywalkin and G Herbo, as evidence. In recent years, this style has become associated with regional sounds in Oakland, Detroit, and L.A.

While Blueface may not have invented this style of rapping, he has come close to mastering his own version of the offbeat flow. And, for listeners unfamiliar with these ‘90s luminaries and the recent intricacies of California’s regional rap scenes, it’s probably their first time hearing anything like it. Almost every YouTube comment on his music videos is some variation of this joke: “Blueface sound like a bunch of seagulls fighting over a chip.” He’s leaned all the way into his music’s most talked-about trait and made it into his calling card.

“If I would’ve said, ‘Mop the floor and catch him slippin’,’ that bar would not be talked about,” he says, referencing his often-quoted “Respect My Crypn” line. “It’s the ‘Hide the wet sign.’ I can’t take that factor out of the music or it wouldn’t be me.” These run-on bars demand repeat plays, part marketing savvy and part unchecked ego.

“I’d rather you be stiff with a stuck look on your face than just bopping, not even listening to what a nigga saying. He could be saying, ‘Monkey, cow, pussy, ass.’ I’m the opposite, I want you to hear me.” Blueface looks out of the tinted car window as we drive through Hollywood, laughing to himself. “And some people say I’m not a lyrical rapper.”

On the way to Blueface’s interview at a radio station in Burbank, the conversation in the car takes a turn when Wack 100 launches into a rant about one of California’s most celebrated voices: Tupac. “Everywhere he went, he turned into that,” Wack says of the late rapper from the driver’s seat. “When you was over there, you had leotards on. When you was up there with the Bay niggas, it was Digital Underground shit.” In the back seat, Blueface nudges him, “You better let that man rest in peace.”

Wack, who got his start in the music industry working with Suge Knight and Death Row Records at the turn of the millennium, seems to love speaking on the topic. On his Instagram, and in past interviews, he’s repeatedly disparaged Tupac’s street credibility, provoking responses from Snoop Dogg, Spice 1, and more. In the car, his grievances are relatively tame: “Just be who the fuck you gon’ be.”

“Some people just want to be accepted,” Blueface suggests.

“I won’t give him that revolutionary shit — that was his momma. He wasn’t no X Clan,” Wack says, referencing the militant Brooklyn hip-hop group who released their debut album seven years before Blueface was born. Wack locks eyes with the young rapper in the rearview mirror, “You ever listen to X Clan, nephew?” He hasn’t.

Earlier that morning, before his Beverly Hills meeting, Blueface had reached a major milestone of music industry success, earning his first entry on the Billboard Hot 100 with “Thotiana.” In the absence of an official video, “Thotiana” has been propelled to viral success by a dance that Blueface has been doing at shows and on Instagram. In the past few months, NBA star Paul George did the dance after hitting a game-winning shot, and Kansas City Chiefs running back Damien Williams used it as his touchdown celebration.

The “Bustdown” dance, as Blueface calls it, is pretty simple; it involves grabbing the waistband of your pants and stretching it outwards while dipping your body to the beat. The song closely recalls the tempo and instructional nature of dance-centered Bay Area rap songs from the early 2010s. Blueface acknowledges he didn’t create the dance, but no one can argue with the fact that he’s popularized it. “I adopted the dance,” he says. “I might not be the biological parent but that’s my kid.” When I ask if his time living with his dad in Oakland had any influence on the dance, Wack interjects from the driver’s seat: “I wouldn’t give a fuck if it started on the moon; that’s the Blueface dance.”

Blueface is an artful opportunist. Just like he did during his first visit to the studio, he seizes situations and makes them work for him. When he had a small buzz in L.A. but wasn’t getting booked for shows, he held Instagram contests for his followers and pulled up to the high school whose name appeared most in the comments. When a fan took a compromising screenshot of his dick during an Instagram Live stream in the shower, Blueface took his own dick pic and used it as the cover art for his next single. He plays into the memes, fitting even more words into each bar, dancing even more animatedly on stage, and making each moment on Instagram even more memorable.

“I’ll just be an arrogant asshole for you,” he tells me at one point. “People always like that, right? That’s what it seems like.” He’s tapped into what entertains people and he’s more than happy to be the one to give it to them.

“I’d rather you be stiff with a stuck look on your face than just bopping, not even listening to what a nigga saying.” —Blueface

But the line between entertaining and offensive can be thin. In one video on his Instagram, Blueface thumbs through a stack of one-dollar bills in a strip club before turning around and throwing it at a stripper’s head. Some people online found it hilarious — after all, it’s not a departure from everything he’s ever rapped about in his songs — others were not amused. “I don’t see how that’s disrespectful,” Blueface says of the video. “Once you signed up to get money thrown at you... I feel like it’s either you want money or respect.”

When applied to his own career, this same logic seems to fuel many of his actions. “If you see the shit that I’m doing, you could tell I don’t give a fuck,” he says. “Even if I’m making a fool out of myself or somebody make a fool out of me.”

The entire premise of your image becoming a meme seems dehumanizing, but Blueface doesn’t mind. He thinks the videos comparing his voice to Courage The Cowardly Dog are really funny. At the end of the day, it’s all profitable as long as you have something to sell. “The whole objective in this shit is to be a meme,” he says. “That’s what this industry is based off of: a bunch of mouths moving, gums popping, no matter good or bad. If the outcome is money, how could it be bad?“

The big question now for Blueface is how he can make it all last. During his meeting at the agency, the people sitting around him at the table throw the word “crossover” around quite a few times. In this context, they’re referring to demographics: Blueface is already a fixture in the “urban,” black markets in various parts of the country, and they’re looking to expand to whiter, more suburban audiences. His reach in L.A. is already impressive. He sold out his first hometown headlining show at The Novo in January. French Montana was in attendance; Seal brought his kids.

When I ask Blueface if he thinks he’ll have to expand his set-claiming, turf-centric sound to appeal to a wider audience, he shrugs. “I could change it up,” he says, citing his recent single “Studio.” Released in December 2018, the song follows a common come-up narrative, and finds Blueface leaning into more melodic territory as he croons, “You wasn’t there from the start, you can’t get nothing from Finish Line.”

But if the success of “Thotiana” is any indication, Blueface may not need to shift his approach to reach the ears and eyes of mainstream America; for rap fans living far outside the areas where the music is made, the novelty of the song’s regional sound may be the very thing that drives its crossover. At the end of January, a video of a group of teenagers from Oklahoma dancing goofily to the song went viral on Twitter. The resounding sentiment was “‘Thotiana’ is cancelled,” as fans mourned the inevitability of white people ruining the song. The next week, “Thotiana” moved up 38 positions on the Hot 100.

“Studio” was Blueface’s first release under Cash Money Records, who announced that the rapper had signed to their Cash Money West division last November. Cash Money West is a joint venture between Wack and Cash Money co-founder Bryan “Birdman” Williams. Cash Money is distributed by Republic Records and falls under the umbrella of Universal Music Group. To make matters even more complicated, Blueface’s Famous Cryp project — which features a significant amount of his catalog up until this point, including “Thotiana” — was released through 5th Amendment Entertainment/eOne in a one-album deal, a representative from eOne confirmed.

In other words, eOne owns the majority of Blueface’s music right now, while Cash Money controls a few singles and everything else to come. Having a handful of labels all pushing his songs at the same time might pay dividends in the short-term, as they each compete to make their slice of the pie worth the most money, but it could also raise long-term issues about the size of Blueface’s slice when it’s all said and done.

In an interview with The Breakfast Club in January, he said he wasn’t aware of the fine details behind his tangled label situation, telling the hosts, “You gotta ask Wack about the other people involved.” People online reacted incredulously, but Blueface is in the same position as many: the vast majority of young artists signing to major labels have little to no idea what their contracts say. During our conversation, he echoes his past sentiment. “I don’t know what deal [Wack and Birdman] got going on,” he says. “I know I got the bag.”

All that Blueface cares about is that he’s hot right now. In just a year’s time, he’s gone from a stay-at-home dad to a rapper who’s impossible to ignore, and he’s done it off the strength of pure charisma. He knows that for every person commenting “Blueface saved rap” under his music videos, there’s countless others who hope his fall-off comes as quickly as his rapid rise. But it’s hard to argue with how well his blueprint has played out so far. “That’s me without the camera on,” he says. “I was Blueface when I was in the hood doing all that other shit. Y’all just now getting to know Blueface. I made this happen. I made you wanna know Blueface.”

On Instagram, Blueface refers to his live shows as choir rehearsals and, in fan videos, he can be seen on stage leading the crowd in sing-alongs, holding his hands out and gesturing like a conductor. In watching his ascent, and talking with him, it feels like he’s done the same thing with his nascent career. On his 22nd birthday, the weekend before we meet back in L.A., Blueface performed in Houston for the first time. In videos from the show, the crowd, crammed face-to-shoulder against each other, scream his lyrics back at him and keep their phones held high over their heads to record every moment. When the first notes of “Thotiana” hit, and he pops his shirt over his head, the reaction — at least on video — is deafening.

Before Blueface plays his final song, he brings a young fan on stage, who says he’s 11 years old. Looking out over the small sea of faces for the kid’s potential dance partner, he asks into the mic, “Who tryna go viral?”