The FADER's longstanding series GEN F profiles emerging artists to know now.

At Gandhi Square in Johannesburg’s high-energy Central Business District, high school students exchange Sho Madjozi songs via Bluetooth. At a nearby intersection, a large screen beams clips of her technicolor "Dumi Hi Phone" video; a few months earlier, that same screen hosted a Nike commercial she starred in. You might spot an Absolut billboard with her face on it and then catch an episode of Isithembiso — Sho has a role as the shit-stirring Tsakani Mboweni on the TV drama — at home in the evening. We’ve had to settle for a mid-morning, mid-week Skype interview because life is hectic for the baby-faced 25-year-old, who recently started managing herself. “What I’ve discovered that I do need is a personal assistant,” she says.

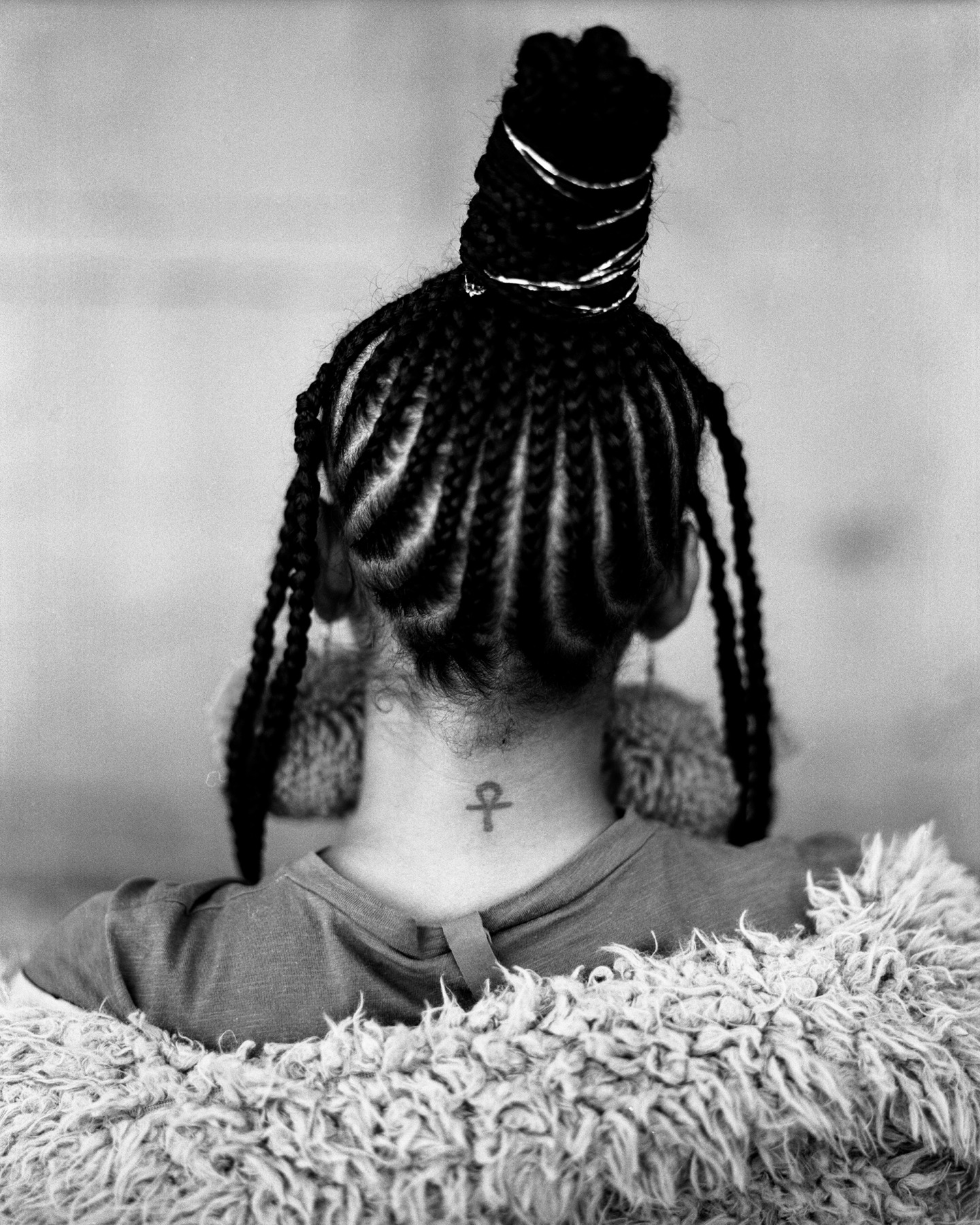

Sho was born Maya Wegerif in the northern province of Limpopo to a South African mother and Swedish father. A village girl raised in a compound full of matriarchs, her stage name was inspired by Vivian Majozi, a fictional character on a long-running local soap. Since returning to South Africa two years ago, following a self-imposed eight-year exile, her profile has risen at warp speed. “My mission is to try and imagine what a young African girl would be without the interruption of colonialism and Apartheid,” Sho says. She had spent the intermittent time falling in love with other parts of the continent, discovering afrobeats, letting go of her dream of a career in politics, and obtaining an African Studies and Creative Writing degree at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

“There was this sense of South Africa being quite isolated [from] the rest of the continent, and [I saw] myself more as an African than just a South African,” she says. “It was frustrating to interact with South Africans who didn’t feel a part of the rest of the continent. I’d come back and they’d be like, ‘What’s it like in Africa?’”

Sho’s plan upon returning to South Africa was to make a living by ghostwriting for local rappers. “I need poetry to survive, emotionally and psychologically,” she says. “But being a poet, financially, is not [easy].” In 2016, the Durban artist Okmalumkoolkat saw her rapping on Instagram and invited her to a recording session. Her contribution to "Tongue Foo Action," an urgent-sounding Xitsonga verse, was done and dusted in about 10 minutes. “[Okmalum] was like, ‘Everybody’s gonna ask who you are after they hear this.’ And literally everyone did.”

For her own work, Sho prefers singles over album. “I like making something today and releasing it tomorrow,” she told W24 last year. “My flow evolves so rapidly, if something drops in two months, it’s outdated.” She’s experimented with different sounds but found a good match in Gqom, the post-S.A. house style that has emerged as the country’s leading musical export. Her 2017 collaboration with the production duo PS DJz “Dumi Hi Phone” is a hi-groove party-starter that became a hit almost instantly upon its release.

Sho writes bright, aspirational verses that embody the near-globalist mission of her years away from home — “I wanna wake in Kampala / Go to sleep in Mombasa / Bust that ass in Kinshasa / Catch a bus to Lusaka,” she raps on Ghanaian-Romanian artist Wanlov the Kubolor’s "No Borders" — and she employs a flexible, multilingual approach to rhyming. "Huku," another Gqom-inflected single, became a surprise hit in South Africa, given that its Swahili raps are more targeted toward the East African market. In just two years, her list of collaborators has stretched from Joburg to Accra.

As Sho manifests her pan-African dreams, her success has coincided with a pivotal moment in not only South African pop culture, but also with a larger trend of youth-scripted narratives aimed at pushing the continent in a new direction. Career politicians have usurped power structures and let shit go haywire — public healthcare is in shambles; the education system is all fucked; corrupt officials get the pass for ill intentions; and violence, directed at women and young children in particular, is alarming.

Sho is finding visibility and openly engaging in difficult conversations about history at a point when the country is questioning the myths it’s been led to believe, and that means something. She’s currently working on a film project that will tell the story of the tinguvu, a thick, traditional wool skirt worn by women of her ethnic group.

“I represent a lot of people, not even just within Xitsonga culture,” she says. “So many people have lived their whole lives having to be split in pieces because at home you’re this, in the village you’re this, but at school you have to be something else entirely and put away your Africanness.”