This beautiful film gets to the heart of Lisbon’s thriving Afro-Portuguese dance music scene

Watch Pai Nosso, a film about grief, faith, and DJ Firmeza, produced in collaboration with The FADER.

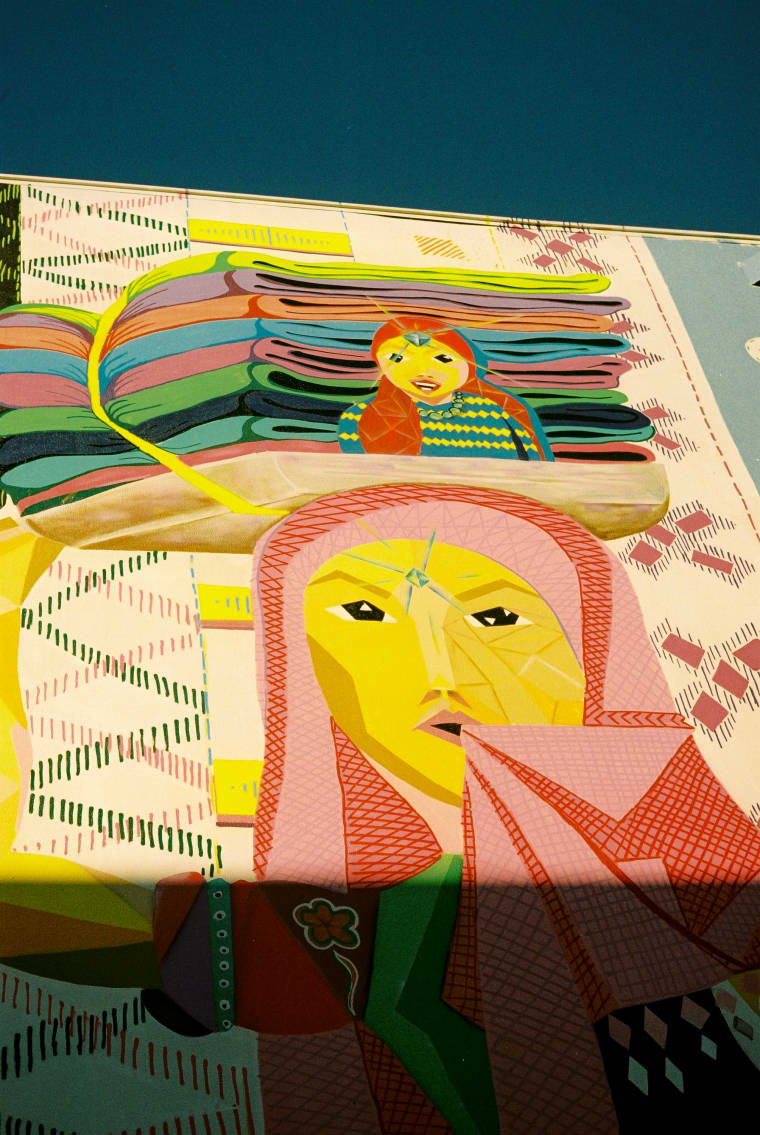

Throughout Pai Nosso (“Our Father”), an emotive short documentary directed by Clayton Vomero and produced in collaboration with The FADER, 23-year-old DJ and producer Firmeza grapples with questions of loneliness and faith. He says, unequivocally, he is not religious; but he laughs off the idea that heaven doesn’t exist. For him the truth is something unknowable, something in between. The intimate film follows him not only as he tackles these big topics, but as he eats in his kitchen, creates music in his studio, and walks around his neighborhood, Quinto Do Mocho in Lisbon, shooting the shit with his friends about dating girls. Simmering beneath these domestic scenes, darkly omnipresent, are two intertwined things: the tight, dense percussion of Firmeza’s music, and the subject of his father, who passed away in 2015.

Firmeza started producing in his father’s house, back in 2009, and he named his debut release Alma Do Meu Pai (“Soul of my Father”). His adrenaline-filled beats bear the influence of his Angolan parents, who emigrated to Portugal in the 1990s — the music takes flight from kuduro, but with sharper angles and harder punches. DJ Marfox, a local scene elder who Firmeza once idolized before he began producing himself, calls the Lisbon-born genre batida, a word that describes the beating of your heart after a car crash. But even among a cohort of fellow artists like Marfox, NÍDIA, and Nigga Fox, what Firmeza makes has a fluttering heart all of its own.

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

“I just got lucky to have found Firmeza beyond his music.” —Clayton Vomero, director

All of these artists have a home in Príncipe Discos, a label launched in the early 2010s. The label’s co-founder José Moura says batida blew his mind the first time he heard it. “We couldn’t pinpoint it. We thought, this is really something we’ve never heard before. It’s not techno, it’s not house, it’s nothing that we know about.” But this new ecosystem of dance music had developed right here in his city, in suburbs like Quinto Do Mocho with large African migrant populations. The problem was that the music had been segregated, to the extent that if DJs like Firmeza were booked to play in clubs in the inner city, they were instructed not to play their own music, but American R&B and pop. Príncipe made it their mission to bring the blossoming scene out of the shadows. “Over the years, I’ve been more empowered to play my own style,” Firmeza told The FADER recently. “And to not give a fuck about what people say, or the stigma that is attached to my own style. I’ve just become myself.”

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

Filmmaker Clayton Vomero was aware of all this when he traveled to Lisbon earlier this year, but was aware of the limitations of capturing a sprawling musical community. “I never set out to tell the story of the Lisbon scene,” he says. “It’s too large and too vibrant to sum up in a short film.” He didn’t know exactly what he wanted to shoot: only that he was interested in the breathless, percussive dance music that was emerging from the capital city’s bairros, or ghettos, and that he was drawn to Firmeza in particular. Vomero had once watched Firmeza on YouTube as he mixed frenetic tunes in a living room. In early 2017, the director was mourning the loss of a good friend, and had packed up his belongings into a storage unit, leaving his home in New York behind for a while. When he met Firmeza in Lisbon, he realized that they had this fresh grief in common, and the film began to take shape.

The pair spent days talking about life and death — via interpreters — and nights bouncing between clubs and friends’ houses. “It wasn’t just his music,” Vomero realized, “But how he looked at life, and how he was coping with the loss of his father and becoming a role model to his family, and then still being an inherently spiritual person who doesn’t really care about religion so much. I just got lucky to have found Firmeza beyond his music.”

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

“We thought, this is really something we’ve never heard before. It’s not techno, it’s not house, it’s nothing that we know about.” —José Moura, Príncipe

In particular, Vomero was drawn to the Portuguese concept of saudade: a perpetual longing, embodied by the woman who waits on the shore for her husband to return after he has set sail. Graves in Lisbon bear the phrase eterna saudade, essentially meaning “eternal longing,” or as Vomero puts it, “a piece of me will long for you forever.”

Batida is not overtly mournful or longing music. But, in Firmeza’s case, you could say it's pierced through with this sense of saudade. It beats to the drum of his parents’ homeland, displaying the musical gifts his father left him. It was largely composed in his darkest hours, as he spent nights alone thinking of what he’s lost — and yet it’s played during his lightest times, seeing people from across Lisbon brought together on dancefloors, in crowds that shout his name. In the final moments of the film, the people of Quinto Do Mocho dance with long limbs and wide smiles outside the flung-open doors of a church. Enraptured by the unifying thrum of the music, they look like they could be in heaven.

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

DJ Firmeza

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero

Clayton Vomero