Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

In the fall of 2007, residents of tiny Saranap, California, were surprised to hear of a proposed $20 million construction project. The plan called for a 66,000 square foot structure to be built within an unassuming neighborhood of single-floor ranch homes, canopying oaks, and sloping, sidewalk-free streets. The renderings depicted a futuristic all-white building of 13 interlocked domes. It was “bigger than the White House,” locals would grumble in public hearings, an “eyesore”; it was “secretive” and “reminds [one] of Waco”; it was “better suited to and more reminiscent of the architecture of Bukhara, Uzbekistan.” It was to be a sanctuary for a religious order called Sufism Reoriented.

Sufism Reoriented had been based in Saranap, an unincorporated village a half-hour east of San Francisco, for decades. They ran a popular elementary school attended by many children outside of their faith; they were recognized for their agreeability, their youth-arts and food-bank charities, and their penchant for dressing in whites and soft pastels.

Their Murshida, or spiritual leader (the word is borrowed from Arabic), was Dr. Carol Weyland Conner, a clinical psychologist. Their anonymous, walled-off headquarters was a former nightclub called the Iron Gate. They were mostly white, largely well-educated, and generally middle-aged or older. They were well-liked, accommodating, low-key. But the tenets of their faith were not well-known.

Some residents, understandably but incorrectly, assumed Sufism Reoriented had a connection to traditional Sufic Islam. Some believed the group members, like the Turkish Sufi Whirling Dervishes, practiced meditative ritualistic spinning. In fact, the Saranap Sufis were part of a larger international community that believed Meher Baba — a cheekily-moustachioed Indian man who preached universal oneness and love until his death in 1969 — was the reincarnation of the Buddha and Christ and God on earth. The proposed sanctuary was intended to last 700 years, at which time Baba was prophesied to return.

Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

Soon after it was announced, a homeowners group called the Saranap Community Association began to lead a pushback. They pointed out that the site of the proposed construction was zoned residential. They argued that the large structure would forever destroy the “semi-rural” identity of the neighborhood. A website, SaveOurSaranap.org, became the hub of the conversation. Quickly the opposition coalesced, hardened, and kvetched.

“People were up in arms,” recalls Ursula Reinhart, a former member of Sufism Reoriented who left the order in 1980. “‘Suddenly this thing is supposed to be built?’ In the website were these comments, and they were all battling back and forth: ‘where does this money come from?’ And me, being an outsider, I just put in — ‘Cheesecake Factory.’”

It was true. While part of the sanctuary’s budget was sourced from the 500-plus congregation’s personal finances, it would turn out that much of the money was coming from one member in particular: David Overton, the founder and CEO of the family-dining chain. Overton had founded the Cheesecake Factory, now renowned worldwide for its abundant comfort-food menu and its rich glass-cased confections, in 1978. In the decades to come the Cheesecake Factory would blossom to nearly 200 locations worldwide, from L.A. to Hong Kong to Beirut.

Nearly a decade before its launch, Overton had become a proud Saranap Sufi. Older versions of the menu cover incorporated a piece of traditional Sufi iconography, a winged heart. At the Cheesecake Factory location nearest Saranap, a ceiling mural features that same winged heart along with the Star of David, the Hindu Om, and other religious icons, presumably a recognition of Sufism Reoriented's respect of all world faiths.

Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

According to Pascal Kaplan, a longtime member of Sufism Reoriented, the group "recognizes the underlying universal truth in all religions brought by the one God who repeatedly comes in human form as the World Teacher." As for the sanctuary budget, according to Kaplan, Overton generously told the order, “whatever you can’t raise, I’ll help fund.”

To the Saranap Sufis, the opposition to the sanctuary looked like plain, all-too-familiar religious persecution. They were portrayed as a cult; they were labeled as mysterious and secretive for their faith practices. To the opposition, the sanctuary was a strange behemoth threatening the very identity of their town. “Saranap used to be one of those neighborhoods where you could walk around and be friendly to your neighbors,” said a local in one public hearing. “Now everybody wants to know what side you’re on.”

This story starts with a house of worship. A unique building, in a quiet part of California. It jumps to D.C. in the ’50s. India in the ’60s. The cover of Rolling Stone. Allegations of mass smoking. Accusations of astral mind control. Where it settles again is a land-use dispute.

In Saranap, the fundamental questions of small-town America were asked — or more accurately, screamed, with bulged neck veins and fists clenched on tabletops. Who gets to define a community? Who gets to decide who belongs?

Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

“In any battle, you have to define who are your friends and who are your enemies. The Sufis were our enemy.” I heard this from a Saranap local that was a member of the homeowners association. For fear of reprisal, he wished to not be named. Let’s call him Bob.

Bob had moved to Saranap in the early ’80s, at which point Sufism Reoriented was already headquartered in town. He’d always considered the members “innocuous people, walking around with this kind of permanent smile on their face. Ha, ha, everything is wonderful.” He never, he makes a point of telling me, had issues with their beliefs. Bob himself had briefly enrolled a child in the Saranap Sufi school.

Then, in the summer of 2008, Bob recalls, “I get this call. ‘We think the Sufis are getting ready to hijack the homeowners association.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding me?! The Sufis?!”

There were rumblings that Sufism Reoriented had identified the Saranap Community Association as a roadblock in their push for the sanctuary. Kathy Rogers, then a member of the SCA, recalls a Sufism Reoriented member named David Dacus, a local architect, attempting to land a board member position, and being rebuffed. “He is very, very volatile, and nasty. I feared him more than anybody else,” Rogers remembers. “We should have been sniffing the wind.”

Saranap is an unincorporated part of the larger Contra Costa County, meaning officially it’s not a city or a town, and does not have its own municipal government. In that relative vacuum of governmental red tape, the homeowners association saw themselves as a last line of defense. And for them, the Saranap Sufis — once a kind, loving, and beneficent neighborhood presence — had curdled into something else.

On July 10, 2008, at the Sun Valley Bible Chapel, the rumored hijacking came to fruition. Coincidentally July 10 is Silence Day, the day on which followers of Meher Baba abstain from speaking in honor of Baba's vow of silence.

It was SCA’s annual election for board members. Voting was open to anyone. Traditionally, attendance was modest. “I came to the meeting and I saw all these cars everywhere,” Bob says, “and I thought, We’re screwed. These are all Sufis.” According to then-members of the SCA, more than a hundred members of Sufism Reoriented were mobilized. Through write-in candidates, they voted two Saranap Sufis — including Dacus — and two allies into a controlling share of the board of the association.

Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

The opposition was stunned. “It was like when the Panzers rolled in as part of their Blitzkrieg,” one SCA member told a local blog at the time. “It was the closest I’ve ever come to feeling raped,” Bob says now. “Violated. I was stick to my stomach. I never experienced that in my life.”

Dacus, who’s led the SCA since 2012, attests the “takeover” was no such thing. “There was nothing nefarious about it. We were accused of busing people in from other parts of the county. Which was a complete fabrication. It was just numbers. Straight-up numbers.” Dacus contends there was no “campaign,” and that the extra crowds “just showed up to vote” that day because they were “civic-minded people.”

(I first email with Dacus, then speak to him over the phone. At several points he speaks glowingly of Sufism Reoriented without identifying himself as a member. When I ask directly, he says that he’s been a Saranap Sufi since the ’80s. I suggest that looks like a conflict of interest. Wouldn’t his allegiance presumably be with Sufism Reoriented, and not the neutral homeowners association? He says that, throughout the fight over the sanctuary’s approval, he relied on his “professionalism” as an architect to stay unbiased.)

The anti-sanctuary side had lost control of the SCA. Rather than wait for next year’s elections to try and take it back, they split off and formed a new, competing homeowners association. Then both sides of the confrontation began canvassing the community. Collectively, thousands of doors were knocked on, thousands of petition signatures were collected. Flyers were mailed out. Campaign-style signs reading “Save Our Saranap” were pinned into lawns.

To the anti-sanctuary side, the argument was plain. This thing was far too large, they argued, and out of place. It did not belong here, in this quaint little town. Sufism Reoriented pointed out that two-thirds of their sanctuary's square-footage would be underground, and so out of sight. But the anti side wanted further compromises in size as well as appearance. “The Sufis said ‘the smooth lines would echo the rolling hills of California,’” Rogers recalls, scoffing. “Yeah. Snow-white and spaceship-looking. You betcha!” To the pro-side, the defense was just as evident. As one local who was not aligned with either side told me, “If the Sufis were a Christian church coming in asking for an 80-foot cross, no one would dare say no.”

Saranap, California, 2017.

Saranap, California, 2017.

Public meetings, held in front of a Contra Costa County planning commission and open to anyone, would sprawl for hours. Each side had lawyers, folksy brawlers locked in endless debate over interpretations of county code and TDMs and EIRs. But public comment periods, in which anyone could speak, generated the most fireworks.

In one 2012 meeting, Cheesecake Factory CEO David Overton came to voice support. He identified as a member of Sufism Reoriented's Board of Directors. He praised the quality of the sanctuary’s architects, which was indeed top of the line: the plans came from the elite New York firm Philip Johnson Alan Ritchie, which had built Central Park West’s massive Trump Tower.

"The sanctuary has been a dream of ours for many years," Overton explained. "All of our members continue to give generously from their savings to make the dream a reality. In addition I have committed to ensuring its debt free completion because I believe so strongly in the principles of Sufism Reoriented: Honesty, financial responsibility, kindness, and service to others. I stand here today to tell you this project is on sound financial footing.”

Overton was attempting to bolster the project’s integrity. But to some, the promise of money felt like a battering ram.

The Saranap Sufis’ religious freedom does “not justify special treatment of the wealthy,” one local stressed in response. “Sufism Reoriented seems to have unlimited wealth,” claimed another. No one actually knew what the numbers were. But there was a sense that the tap would never run dry. (In 2003 Sufism Reoriented was granted non-profit status as a religious organization. In their last tax filing as a for-profit entity, they listed over $16 million in funds.)

The language would become pitched, heated, melodramatic. It felt, a bit, like a community finally having a frank, long-put-off conversation. It also felt, a bit, like the classic Twilight Zone episode, “The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street,” in which a quiet suburb experiences unsettling power outages and subsequently falls into a riot of paranoid recrimination. The sanctuary was the trigger. And now the community was letting it all out.

Mechanical engineers, on the anti side, passionately argued zoning violations; rabbis, on the pro side, pointed out religious discrimination. “I will keep my comment to the trees,” said one woman, her voice quavering, “who cannot speak for themselves.” “The word isn’t proud,” said one local. “I am grateful that the Sufis are in our neighborhood.”

Sufism Reoriented's Pascal Kaplan.

Sufism Reoriented's Pascal Kaplan.

The softly arching domes are “a physical expression to the faith principles of a congregation,” Kaplan said. The proposed sanctuary was “sacred architecture.”

Opponents of the sanctuary were nearly unanimous in expressing their support for Sufism Reoriented’s right to worship. Some made a point to study the religion, to respect it even as they clashed. “Sufis worship the pure love for all forms of life,” one woman said. “The question that I have — do you love us, the Saranap neighbors, too?”

But ugly, explicit religious hatred would surface. “The Sufis’ project is a mosque with teachings from the Koran,” railed a fortysomething man named Steven, incoherently, in one meeting. “What other buildings in the area are made of glow-in-the-dark circles, to no end, like the sign of infinity, the time our neighborhood will be dealing with this monstrosity? We don’t care that you eat a lot of cheesecake.” Then he laid down what sounded like a threat.

Others had argued that construction would trigger aggression and cause permanent hearing loss in children, or force homes teetering off the sides of cliffs. Steven, dressed mildly in a white polo shirt and sweater vest, went further: he promised that if construction somehow harmed his own family, “I will make sure there is hell to pay.”

Later in the same session, Pascal Kaplan of Sufism Reoriented took to the lectern. Dapper in a light summer suit, speaking calmly and quietly, he recalled his doctoral studies in theology at Harvard, where he’d read extensively about “unintended religious bias.” He explained that it comes “not out of malice” but simply because people are “unfamiliar with the tenets, symbols, and theology” of the faiths they are biased against. Respectfully, he pushed back.

Freedom of religion is a foundational American mandate, considered unimpeachable. It’s in the First goddamn Amendment. What Kaplan seemed to be saying was that this was a small group and their messianic beliefs were, yes, unfamiliar but no less valid than the messianic beliefs of, say, Judaism or Christianity. That they believed in respect and universal love, and that they believed they deserved it in return. And that right here, in little Saranap, this was a chance for a country that considers itself truly free to put up or shut up.

The softly arching domes, the color white: these are “a physical expression to the faith principles of a congregation,” Kaplan said. The proposed sanctuary was “sacred architecture.”

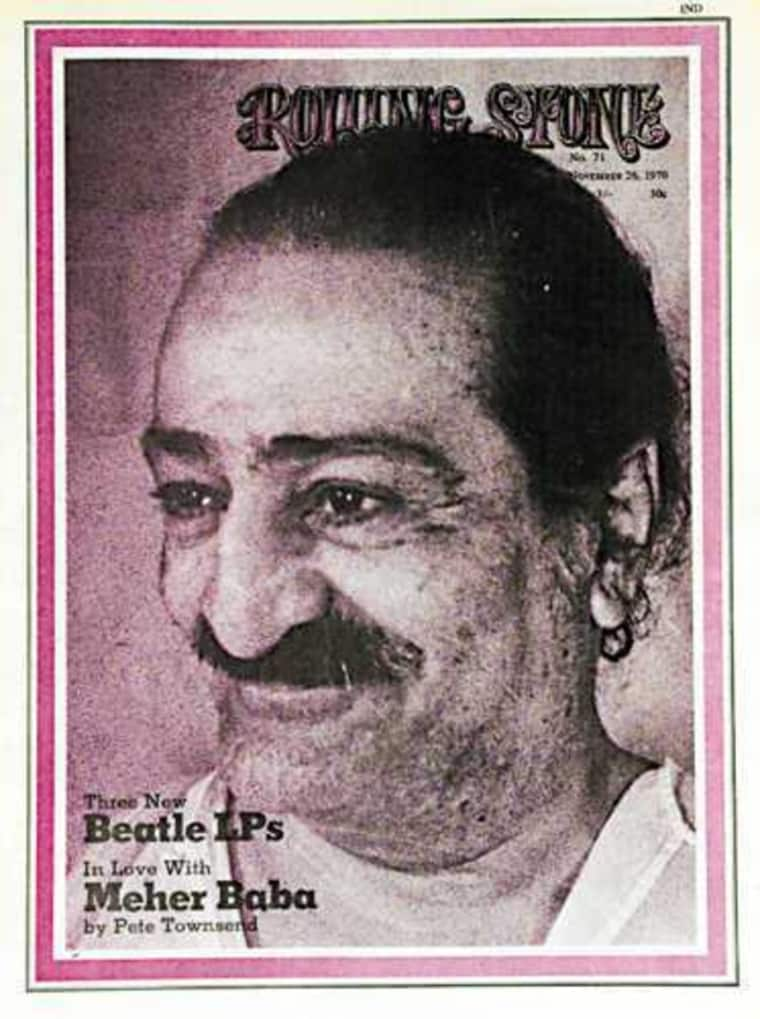

Meher Baba on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1970.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone

Meher Baba on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1970.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone

The cover of Meher Baba's best-known text, God Speaks.

Courtesy of Dodd Mead Publishing

The cover of Meher Baba's best-known text, God Speaks.

Courtesy of Dodd Mead Publishing

In 1970, Meher Baba landed the cover of Rolling Stone. The article was written by The Who’s Pete Townshend, who, at the height of his fame, had become a Baba Lover, as followers of Baba self-identify. The Who's classic jam "Baba O'Riley" is a nod to Meher Baba; it was written as part of a never completed rock opera, Lifehouse, that Townshend envisioned as an adaptation of Baba's ideas. Baba had died — or dropped the body, in his followers’ parlance — in 1969, at the age of 74, in the throes of his own international renown.

In the piece Townshend relates the guru’s biography. How he was born in a town called Poona in the west of India in 1894. How he studied under five Perfect Masters. How, one day, one of those Perfect Masters hit Baba with a stone right between the eyes, and how at that point Baba came to understand his destiny as a Perfect Master himself. How he took a vow of silence in 1925 that lasted the rest of his life.

As Baba would explain, "Because man has been deaf to the principles and precepts laid down by God in the past, in this present Avataric form I observe silence. You have asked for and been given enough words. It is now time to live them."

“At first his words were encouraging, his state of consciousness and his claims to be the Christ exciting and daring,” Townshend wrote. “Later they became scary. He made me weep for hours.” Baba had gotten inside his head: Townshend had been a prodigious drug user, he said, until he came across Baba’s declaration that narcotics were not the way to higher consciousness. Now Baba was his drug. “The crux of it is, I am now stoned all the time.”

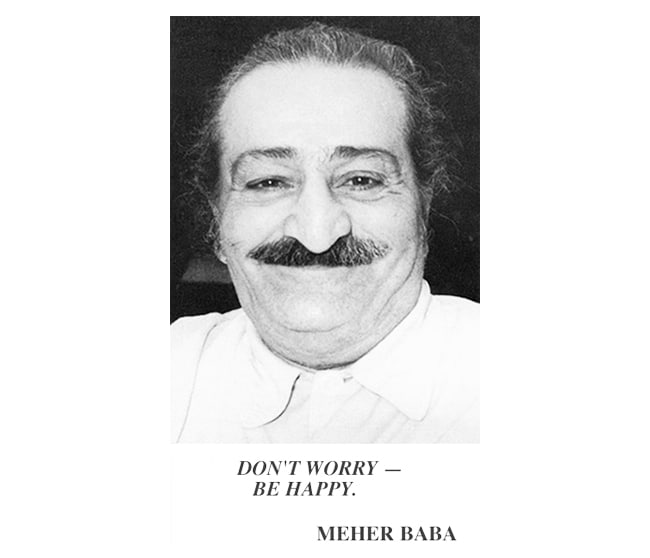

There were tens of thousands of Baba Lovers throughout the world (then as now, there are no exact counts). In the U.S., they clustered around the Bay Area. San Francisco residents in the ’60s would have likely been familiar with Baba pamphlets (“God In A Pill? Meher Baba on L.S.D. and The High Roads”) and aphorisms. “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” was Baba’s coinage; it’d appear on postcards and billboards. (Bobby McFerrin spotted the phrase while visiting the San Francisco apartment of the jazz duo Tuck & Patti in San Francisco. In 1988, he took his corresponding song to No. 1.)

From Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, The Beatles’ favorite, to Rajneesh, the “sex guru,” divinely-touched figures from India were a cultural mainstay of 1960s America. Ursula Reinhart, the ex-Saranap Sufi, recalls a trip to India in the ’60s. “There were so many holy men that sat around the Ganges in orange robes smoking hash,” she laughs. “Thousands of them!” Through traveling companions, she was told to seek Meher Baba.

Baba, long at that point voluntarily mute, would use a wooden alphabet board to communicate (a follower would vocalize the Master’s messages). Baba asked her: who do you think I am? “I said, ‘I have no idea,’” Reinhart recalls. “And he said, ‘I am God in human form, and I know this because I constantly experience it.’” She was rattled. She was convinced. “The authority with which he said it — I believed him.”

Ursula Reinhart with a photo of Meher Baba.

Ursula Reinhart with a photo of Meher Baba.

The greater world of Baba Lovers was open-ended and non-hierarchical. It was shaggy and proto-hippie. Sufism Reoriented, founded in 1952, had structure: it was a proper church of Meher Baba. A Washington, D.C. resident named Ivy Duce received a charter for an organization from Baba directly. She’d been heading a group who looked to the traditional Muslim Sufi musician and saint Inayat Khan as their spiritual forbear. When they turned to Baba instead, they were “Reoriented.”

Duce was married to a government-relations executive at the Saudi giant Aramco, the biggest oil company in the world. She was prim, proper, a Washington D.C. society lady with uniformed butlers and a home full of antiques. She was personal friends with the Saudi royal family. Her original inspiration for a Sufism Reoriented sanctuary was Manhattan's famously grand Frick Museum.

In retirement, Duce and her husband would move to the Bay Area, where she would continue her role as Murshida of Sufism Reoriented. Duce imbued the order with an aspirational, well-heeled manner. Even as San Francisco was overtaken by the wooly, druggy counterculture, Sufism Reoriented remained unblinkingly polite. Both spiritually and socioeconomically, there was a certain elitism associated with membership.

A common Mehar Baba card from the 1960s.

A common Mehar Baba card from the 1960s.

In 1979, two years before her death, Duce appointed a psychologist named Jame MacKie as the new leader of Sufism Reoriented. (Female leaders are known as Murshidas; male leaders are known as Murshids.) According to Sufism Reoriented’s interpretation, Meher Baba had promised the order would be led by Perfect Masters until his return. That meant MacKie was spiritually illuminated. In the parlance of the order, he was on the 6th plane of consciousness.

MacKie was charismatic, eccentric, and particular in his habits. He spoke softly, wore ballet slippers, was chauffeured in a Cadillac, and chainsmoked. (An aide would regularly follow him around, ashtray extended.) According to Bill Gannett — a Baba Lover from Berkeley and a longtime critic of Sufism Reoriented — after MacKie, the order began exhibiting the signs of suppression of individual choice that defines cults.

“Sufis started to wear white because Jim MacKie wore white,” Gannett claims. “Sufis began to smoke because Jim MacKie smoked. An astonishing groupthink began to pervade the membership. Sufis consolidated their living arrangements in shared buildings and began to decorate their spaces similarly.” To this day, Gannett says, Saranap Sufis are discouraged from living alone.

Like every other Baba Lover I speak with, Gannett is never sanctimonious about his beliefs. There's a quiet confidence, and a shrugging-off of skepticism. "Meher Baba declared he was the Avatar, the God-man," he says. "It's a lot to swallow! His claim is emphatic! And his followers, of which I am one, believe it." As I understand it, Gannett's grudge with Sufism Reoriented is their attempt to own interpretations of Baba's message.

“This structure, this multi-million concrete bunker, it’s meant to safeguard their archival treasures,” he says, referring to teaching by Sufism Reoriented Murshids and Murshidas, past and present, which the order has carefully preserved. “In the times of trouble and duress that will come, they believe that these materials will guide humanity to the promised land.”

In an internal Sufism Reoriented newsletter from the late '70s, when MacKie was ascending the ranks, a strain of fervent devotion is implied. The order had begun discussing MacKie’s “food preferences, soap preferences, silver polish preferences,” the newsletter writer explains. Because of MacKie’s fondness for elaborate chocolate desserts, “every meal featured 'chocolate fantastic' or 'chocolate extraordinaire.’” People threw themselves into menial labor: “one young Sufi mother … had forgotten to pick up the ironing” for MacKie, and as “she hurriedly drove to the rendezvous spot [she] prayed that no one else had been assigned her bundle.”

It was shortly after MacKie took over that Ursula Reinhart — the Baba Lover who'd met Baba in India — left the order. Before she did so, she had a one-on-one meeting with the new Murshid. “He was rolling his head and waving his arms,” she says. “He was directing astral traffic or something. He told me I had a brilliant white light coming out of me and I cracked up.” Reinhart felt this was cheap emotional manipulation — not at all the genuine emotional connection that had made her a Baba Lover.

James MacKie, the former Murshid of Sufism Reoriented.

Courtesy of Sufism Reoriented

James MacKie, the former Murshid of Sufism Reoriented.

Courtesy of Sufism Reoriented

Folks like Reinhart were the exception. For Leroy Parker, a painter, arts professor, and Saranap Sufi, MacKie was the real deal. “Murshid Jim, he could burn your ass,” Parker recalls, in a joyful hyperbole. “He’d walk in the room and even if you didn’t see him, the room would be melting. He told us many things. Amazing things. Everybody knew goddamn well that he was sent by Meher Baba.”

At some point, a certain conspiratorial bent had been infused into the sanctuary faceoff. Several people would whisper to me that MacKie had done his PhD on mass hypnosis, as if to suggest the source of his mysterious control. In fact, according to the University of Utah’s records, MacKie’s 1963 dissertation was a plain-sounding study on brain damage.

For the majority of the order, life in the ’80s continued placidly. The anguished spiritual searching that had led the order’s members to Meher Baba in the first place was now a thing of the past. The answers they’d sought had been provided. They could now go about pursuing careers — the order was full of doctors, lawyers, and other professionals — and building families. MacKie could even help shape such life decisions. Pascal Kaplan, the longtime Saranap Sufi, told me that despite a strong desire to continue his work as a professor of world religions, MacKie instructed him to go into software accounting.

When I ask Kaplan about what some interpret as MacKie’s untoward influence over the order, he answers with equanimity. “It’s hard to respond to comments like these, since there is so little context in Western culture for understanding spiritual figures and the learning that unfolds within spiritual communities,” he says. “Certainly, there are a handful of people who hold those views and feel they are justified in doing so. That was not our experience of life when Murshid MacKie was our teacher.”

Before his death in the early 2000s, MacKie would pass leadership onto Dr. Conner, the current Murshida. In that way, the order’s leadership continues to connect itself directly, from MacKie to Duce to Meher Baba. I am not able to speak directly with the current Murshida. ("She is focused on a set of work that does not allow her interruption," a representative explains when I reach out). Of the sanctuary, Dr. Conner has said that her desire is "to give outward material form to the still, sacred space at the center of the human heart.”

Carol Weyland Conner, the current Murshida of Sufism Reoriented.

Courtesy of Sufism Reoriented

Carol Weyland Conner, the current Murshida of Sufism Reoriented.

Courtesy of Sufism Reoriented

I spoke to a thirtysomething California resident who grew up within Sufism Reoriented but did not become a Saranap Sufi himself. Out of respect for family members who are still in the order, he asked to stay anonymous. The man described his childhood as not without its quirks. He recalled how MacKie's smoking influenced others to take up the habit; he recalls the light-colored motifs. He says that Techline, a “shitty office-furniture maker,” was popular in the community because of its various white furniture options. “There was a lot of white cabinetry.”

Ultimately, he spoke of Sufism Reoriented much like any secular adult who'd grown up in a religious household. Yes, he'd rejected the tenets of the faith. But his early life was “friendly and warm. I felt that the adults around me genuinely cared about my wellbeing. I was one of those brooding, loner children, and I probably could have had a much worse childhood if I was in a less nurturing environment.”

It was also in the ’80s, during MacKie’s time as Murshid, that David Overton began building his Cheesecake Factory empire. Overton started off in Saranap in 1970, humbly, baking and selling his mother’s cheesecake recipe out of his home. In 1974, he moved to Los Angeles to go into the cheesecake business with his parents full-time; in 1978, he’d officially open the restaurant’s first location. By the end of the eighties, he’d be popping open franchises throughout Southern California.

The restaurant has become a cornerstone of the American suburban experience, and a bastion of mass-market efficiency. Collectively, the Cheesecake restaurants serve more than eighty million people a year. In 2012, The New Yorker even suggested the health-care industry could be saved if it operated more like the Cheesecake Factory.

Through a spokesperson for the Cheesecake Factory, Overton declined The FADER’s request for an interview about how his faith played a part in the building of the franchise. According to Kaplan, “So much of David’s business life was under the wing of Murshid Jim.”

A ring depicting Meher Baba's image.

A ring depicting Meher Baba's image.

On February 29, February, 2012, after years of swirling animosity, the Board of Supervisors for Contra Costa County was ready to cast their final votes on the sanctuary's construction. In order to accommodate public interest, the meeting was moved from a hearing room into the 800-capacity Lesher Theater. Over the last few hours, the same core issues were dug into again: insufficient parking, inappropriate easements, religious freedom.

Finally, at the end of the meeting, the moment came. “We have a motion before us,” the Chairwoman of the Board said, plainly, quickly. “All in favor say ‘aye.’” The board responded with a flurry of ‘aye’s. The ‘ayes’ were unanimous. The sanctuary was approved.

Later, when asked to explain their defeat, the opposition would argue that the Board of Supervisors, populated by non-Saranapians, never understood the highly localized needs of Saranap. They’d say that the Board was overly business-minded, overly pro-development. That it was uninterested in the preservation of the neighborhood’s true character.

Because of a federal statute called RLUIPA — the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act — Sufism Reoriented was allowed to build the sanctuary without having to rezone their residential land plot. One assumes Senators Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch (respectively, a Catholic and a Mormon) were not thinking of Meher Baba when they pushed the law through Congress in 2000. But the statute aims to boost expression of religion in the face of recalcitrant parties. In that way, the Saranap sanctuary case reads like a classic RLUIPA utilization.

Some lawyers feel the law — which opens the door to the possibility of endless, expensive federal litigation — gives religious organizations leverage over cities that they’d never before enjoyed. Later, members of the opposition would come to believe RLUIPA had doomed them from the beginning.

Marci Hamilton, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that RLUIPA is unnecessary because religious organizations by and large do not face such outsized resistance that they need protection beyond that already afforded by the First Amendment. “There's a lot of respect for religious organizations in the United States," Hamilton says. "The organizations that have a target on their back right now tend to be in communities that have an anti-Muslim bias."

Which suggests another issue, one never explicitly articulated in the Board meetings, never really brought up at all: How much influence on the final decision did the specific demographics of Sufism Reoriented have? Recently in Bayonne, New Jersey, a mosque proposed for an empty warehouse on the outskirts of town was repeatedly, flatly rejected by the local zoning board. Is it easier to find support for religious freedom in America when you’re white and well-off?

Ira Deitrick, the President of Sufism Reoriented.

Ira Deitrick, the President of Sufism Reoriented.

For supporters of the sanctuary, it was a simple boon for progress. The NIMBY-ists, all those afraid of the new, had lost. Says Ira Deitrick, the president of Sufism Reoriented, “In many people’s minds, somehow, we were an alien force, a cult, a threat. For whatever reason, even though we’d been in this area all this time, we seemed to represent significant change. And it’s hard for people to live with change.”

The fight had officially ended. The force majeure of reality set in. Ground broke in the spring of 2012. But the relationship between Sufism Reoriented and the anti-sanctuary opposition never cooled off.

Over their decades in Saranap, Sufism Reoriented had bought up parcels of land when they could afford to. Currently, a local developer is pushing forward an apartment building and retail space at a relatively towering seven stories, or 75 feet. The proposed site of construction was sold to the developer by Sufism Reoriented. A majority of its members, many who live in or near the area being developed, have been highly supportive of it (via both emails to Contra Costa County and presence at community meetings). Meanwhile, the contingent of Saranap that had fiercely fought to maintain the “semi-rural” nature of town is apoplectic all over again.

Within that lingering, sticky paranoia, unproven suspicions linger. “They’re building a colony,” one local told me. “They’re working on their colony.” Added Rogers, “They’ve got a lot of money but they need the people. They have an aging population with very few children. They gotta get this thing up and rolling. They wanna be within walking distance of the sanctuary. Everybody wears white flowing clothes and they want to flow into the sanctuary. It’s perfect. Machiavellian, but perfect.”

It's theoretically possible that, as a condition of sale, the developer mandated that Sufism Reoriented vocally support the high-rise project. Sufism Reoriented says its supportive members simply see the project as an ameliorative neighborhood restoration. And for the record, Sufism Reoriented does not proselytize. Meanwhile, the same questions hang around: is the opposition fueled by religious hate? Or legitimate zoning concerns?

During the fight over the sanctuary, the opposition had presented a strong case. The site of the sanctuary was zoned residential. The plans for the sanctuary did seem out of step with the neighborhood. It was obstructionist, to be sure. But obstructionism can serve a purpose. The same people that are currently resisting the history-dissolving effects of gentrification throughout any given American city could also be dismissed as obstructionist.

Sufism Reoriented had presented a strong case, as well. Ultimately no variances were needed, no rezoning. All environmental and design conditions were met. The Board of Supervisors approved construction unanimously. The order owned their land. And they believed that, at least in this small sleepy patch of the state of California, that meant they could worship on it however the hell they pleased.

Members of Sufism Reoriented inside and outside their sanctuary. Saranap, California, 2017.

Members of Sufism Reoriented inside and outside their sanctuary. Saranap, California, 2017.

In early 2017, nearly five years after approval was secured from Contra Costa County, Sufism Reoriented opened the doors on their sanctuary. A few months later, on a sizzling Sunday afternoon, I visit.

At the front entrance I’m greeted by Pascal Kaplan and Ira Deitrick, the president of the order. Both are in slacks and light-colored dress shirts. Kaplan is peaceful, moderate, almost fuzzily warm. Deitrick, despite a neck bowed with age, gives off a scrappy, old-school, pugilistic vibe.

“We don’t go out and try and get publicity,” Kaplan explains to me, with a neat smile. “We said yes to you even though it looked like — why? I looked at The FADER and I thought, Wow, these people are really counterculture. Then I thought — look at us! And Murshida Conner told us, ‘If somebody comes to us on their own, well, say yes.’ So. Here you are!"

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

Deitrick raises his head off his chest to hammer home his points; a gold ring depicting Meher Baba’s image glistens on one hand. “This is to be our sane and stable foundation for 700 years, until Meher Baba comes again,” he says, gesturing at the entrance. “And when we told that to the structural engineer, he said — 'Do you realize what state you’re in? Do you know what happens in California?!” He laughs as he speaks, incredulous not at the claims he’s making but at the grandness of their sweep.

A quietly burbling front fountain is built out of fetching black Bangalore granite. Marble covers the front entrance, an intensely-durable type found only in Carrara, Italy. (In 128 AD, Carrara marble was famously tapped for the construction of Rome’s Pantheon). The building is 90 percent steel, with special reinforced shear walls and an external layer of monolithic concrete.

Initial budget estimates had been around $20 million; according to information provided by the Contra Costa County tax assessor, the final budget was somewhere north of $35 million. And the structure, I’m assured by Deitrick, has been built to last through all natural disasters and earthquakes, including “the great big one.”

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

Inside, it is cool and still and silent. I slip off my shoes, as is sanctuary custom, and we move with careful intent through the cavernous structure.

Further below earth are rooms and rooms of performance spaces and studios — for dance, for music, for theater — and audiovisual recording suites to support the order’s expression of love for God through the arts. Sufism Reoriented even has something along an in-house pop star, Mischa Rutenberg, who boasts a back catalog of uplifting, anodyne jams about love, hearts, and unity. (A sample lyric: “The humorist, the fatalist, the terrorist, the optimist / All are one.”)

The main prayer hall is a grand circular space, all white with gold trimmings. The center emblem of the marble floor depicts symbols for major world religions and the phrase “MASTERY IN SERVITUDE.” On Friday evenings, closed services are held. An orchid in a clear glass vase marks where Murshida Conner sits and teaches.

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

Inside the Sufism Reoriented sanctuary.

The sanctuary had felt, for the most part, pleasantly deserted. Passing by the kitchen, though, the automatic doors slide open to reveal a small bustle of folks in cook whites. “We do all our own cooking, serving, cleaning up,” Kaplan explains, as we gaze at the scene. “We clean our bathrooms. We do everything. It’s serious!”

This space in particular was overseen by David Overton, Kaplan says. It’s a plus-sized recreation of a Cheesecake Factory kitchen (“because we’re amateurs and we need more space than professional chefs”) and is pumping out 600 meals a day. All recipes were designed by Murshida Conner. “And the food is so good it’s amazing,” Deitrick says. “It’s just” — he breaks for a happy chortle of disbelief — “so, so good.”

In one tall hall, I’m greeted by an arresting massive nude gold figure reaching for the heavens underneath a downpour of natural light. This is the New Being. It’s 40 feet, 11 tons, and took over 100 people over nine years to build. At its base are amoebas, troglodytes, snakes, pahoehoe lava, ferns, fish, worms, and a monkey. At its top are acrylic butterflies. It’s a striking depiction of spiritual progress.

We walk slowly up a set of stairs to better look into the Being’s face. It’s eyes are closed, and its head is tilted back in an intense approximation of utmost, near-orgasmic serenity. “This is the real ecstasy,” Kaplan says, in respectful awe.

This, too, is looked after for the foreseeable eternity: it’s placed on anti-seismic base isolators, a protection not yet afforded to Michelangelo's David; a nearby rail has curved gap, so as to provide space for the figure to shift to the left during a theoretical earth tremor. “We wanted to preserve the left hand!” Deitrick bellows. “When the big one comes it’ll still need a left hand!”

The New Being, a sculpture inside Sufism Reoriented's sanctuary.

The New Being, a sculpture inside Sufism Reoriented's sanctuary.

During the land-use fight, it had been impossible to fully divorce emotion from the conversation. All these years later, the only clear thing was the facts: Sufism Reoriented were better organized, better funded, brasher in their actions, more confident in their convictions. The opposition had been outmaneuvered, outgunned. Who gets to define our communities? Whoever has the resources and the will to get their way. In the simple language of our treasured American wherewithal: the Saranap Sufis had won.

Now, there was a force of unity here, a force of commitment. And there was a joy. Look at this wild dream we had all these years ago, Deitrick and Kaplan seemed to be saying. Look at how we worked to make it real.

From the outside, at first, the sanctuary was not as imposing as it seemed in the renderings I’d seen online. Maybe that was due to the now immutable fact of its existence; maybe I’m just partial to circles. It was certainly surreal to roll into a lush, scruffy bit of brown-and-green suburbia and see domes of blazing white. But it was positively surreal — a step toward quietude. Traveling farther down into the pale nothingness, in the calming presence of my devoted Baba Lover guides, I feel more and more removed from the outside world.

That, in no small part, is the whole point. To believe you can conquer 700 years of future requires a special kind of insular single-mindedness — a special kind of chutzpah. I wondered: even if the building becomes the only man-made structure in North America to survive all manner of calamities for centuries henceforth — how do you know there’ll be anyone around to inhabit it? How do you know this will all survive?

“If Meher Baba is who we think he is …” Kaplan answers me, with a small smile. He shrugs, trails off, picks up again, with some force. “It’s not in our hands!”

“It’s his,” Deitrick says, echoing the fervor. “The order is his. The building is his. It’s directly under his guidance. Meher Baba does that.” Down here, under the earth, under the domes, in the pure white, in the still and quiet, he sounds about as sure as anyone I’ve ever heard.

Sufism Reoriented's sanctuary. Saranap, California, 2017.

Sufism Reoriented's sanctuary. Saranap, California, 2017.