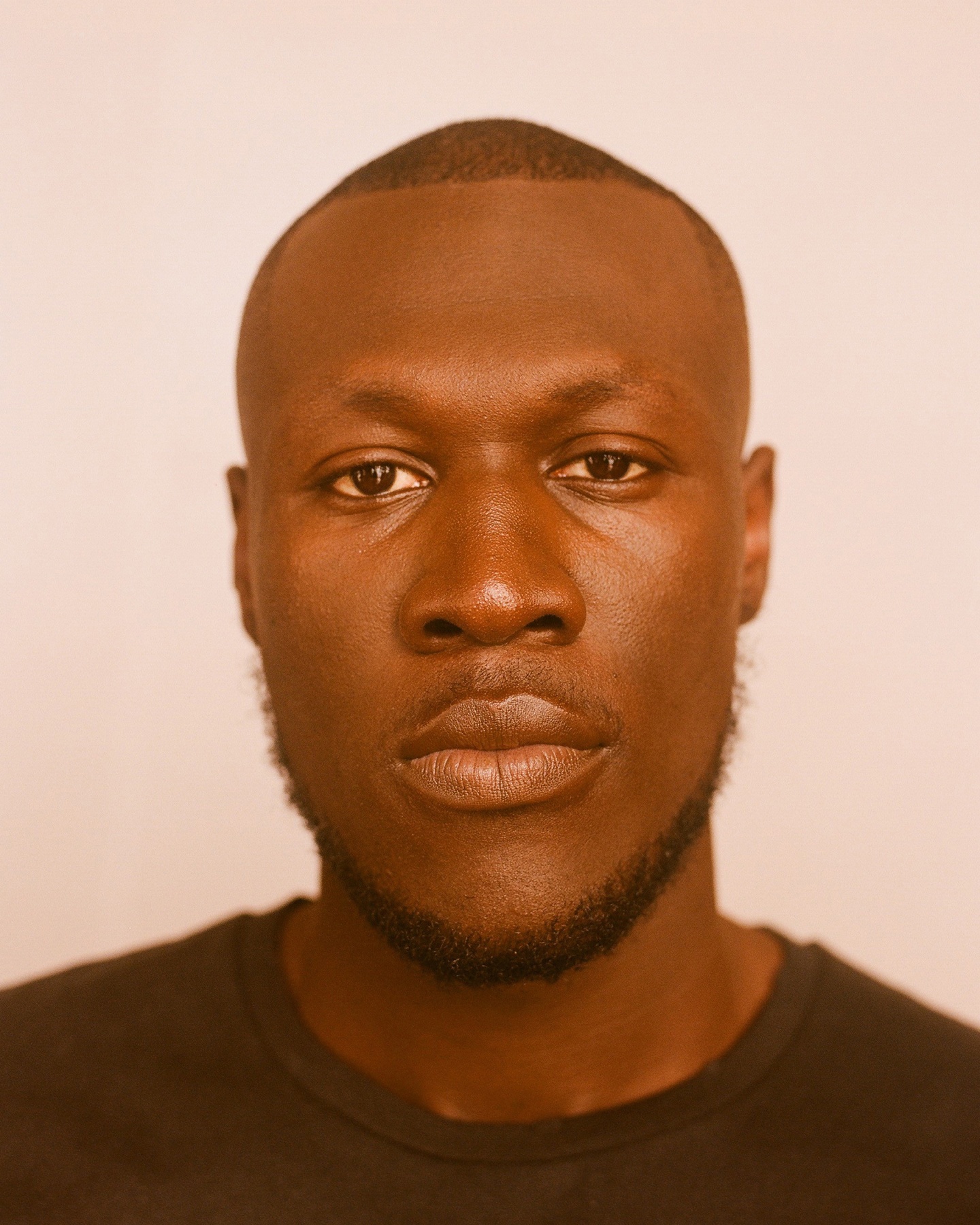

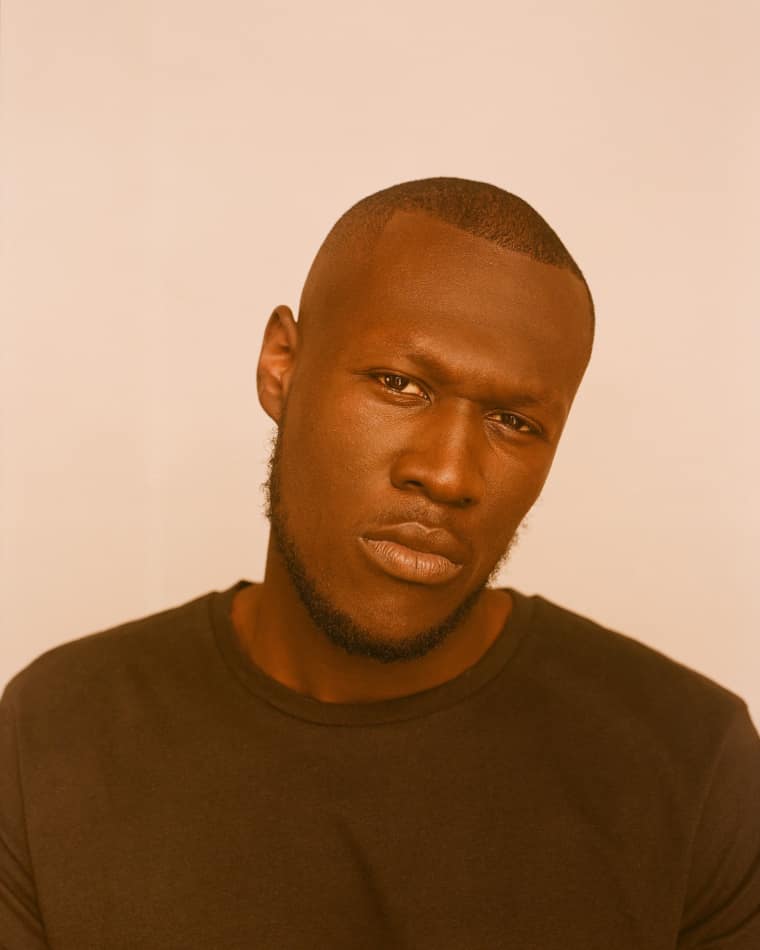

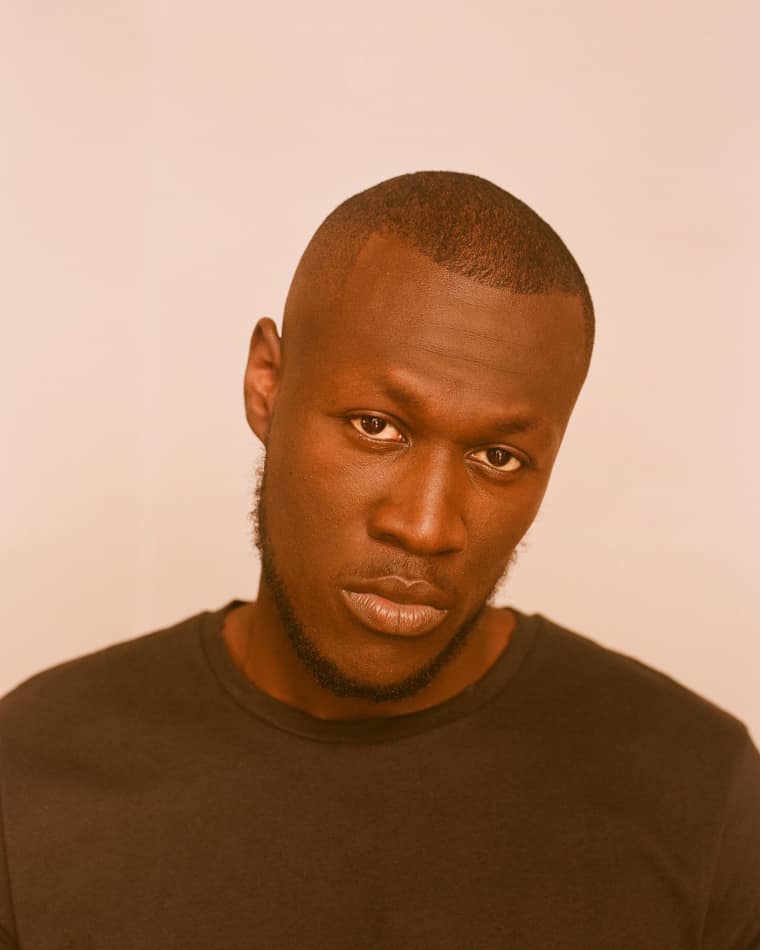

Topman T-shirt.

Topman T-shirt.

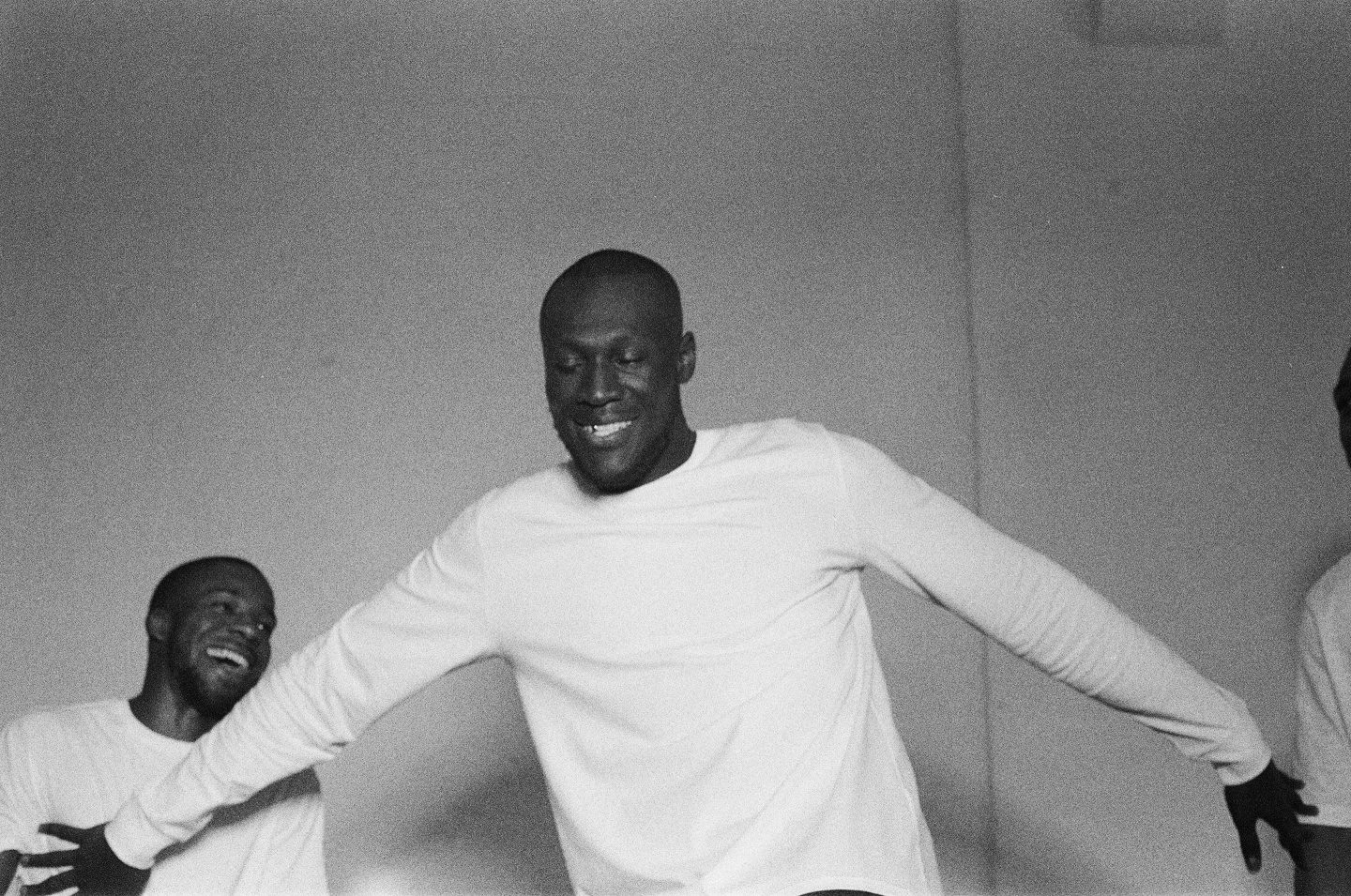

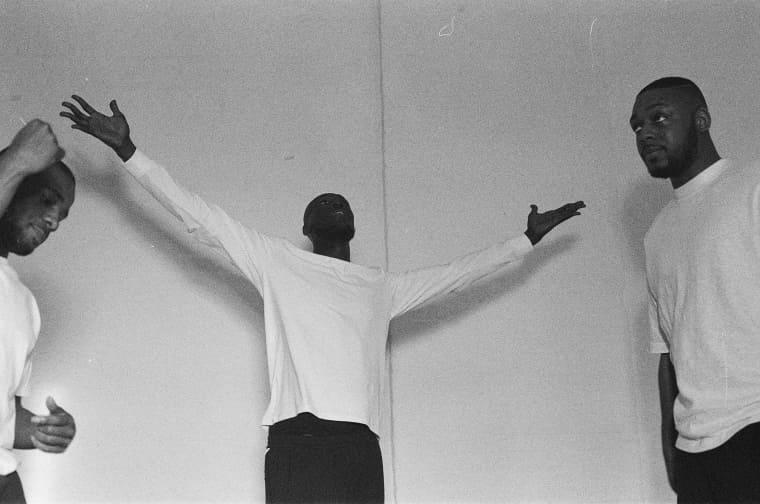

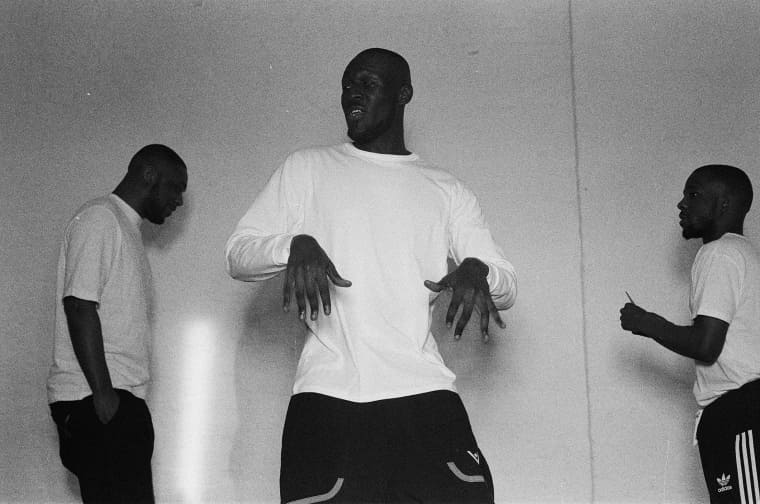

“It’s very simple,” Stormzy says. “We need more slow-motion cutaways. And I need eight black kids.”

It’s 1:30 in the morning, and he’s shooting a video for his single “Cold,” which is already cool, he says, but has the potential to be iconic. The shoot was supposed to wrap tonight, and the assistant director is meant to fly to South Africa tomorrow. Now, he looks alarmed. Stormzy steps outside and drags contemplatively on a Benson & Hedges Dual cigarette.

“We need to do another day,” he says.

All night, Stormzy, who is 23, has performed spectacularly, jabbing and shrugging and sometimes dancing, his angular 6'5" figure gliding across the set. Between takes, he walked straight to the playback monitor, catching small things that could be improved, noting that he should vary how he wears his hood, and giving out instructions on the camera angle. The team around him have been quiet while he speaks, deferring to him like they would a director. He could be: though no one will confirm whether it’s Stormzy, the clip is credited to a pseudonymous “Floyd Sorietu.”

As he smokes, his idea pours out fully formed. He wants to dress the children in suits, doctors’ uniforms, football uniforms, royal regalia — to make them feel “G’ed up.” To him, “Cold” is more than a gassed-up grime tune. It’s a song about self-belief, meant to empower his younger, black, working-class fans. He won’t put out a video that doesn’t carry the same resonance.

This isn’t surprising: Stormzy is known to not settle for less. When The BRIT Awards, the U.K.’s Grammys equivalent, failed to nominate any artists of color in 2016, he responded with a freestyle asking, “What, none of my Gs nominated for BRITs?/ Are you taking the piss? Embarrassing.” As a result, he took a meeting with BRITs chairman Ged Doherty, who later invited 700 new judges to vote for the show’s 2017 installment.

Some critics say that there’s no point looking to the BRITs for validation. The MOBO Awards — for “Music of Black Origin,” founded in 1996 — are more than good enough. “But The BRITs is a place where they basically say, ‘These are the elite artists of the British music scene,’” Stormzy tells me. “I am trying to be respected as one of those elites. I always say: infiltrate.”

Stormzy was born Michael Omari on July 26, 1993, to Abigail Owuo, a single mother who emigrated to London from Ghana. His mom and two older sisters, Rachael and Sylvia, referred to the baby as “Junior.” Stormzy shared a room with his younger half-brother, Brandon, and the family lived in Thornton Heath, a bustling suburb in the south London borough of Croydon. In the area, Stormzy was the kid that everybody knew.

“You couldn’t really avoid him growing up,” recalls Tobe Onwuka, 25, who grew up one street away and is now Stormzy’s manager. “He was always known for his talent and charisma. We would have these house parties when we were younger, and as soon as Stormzy stepped in, you could feel his presence.”

Abigail raised Stormzy to believe that he was the “best thing since sliced bread.” As a child, he imagined growing up to be prime minister. She surrounded him with hiplife and gospel, and took him to the Elim Pentecostal chapel every Sunday with his uncles and aunties. “In Ghana, they are very connected to God,” Stormzy says now. His connection to his faith “stems back from that.” Today, Abigail is temporarily in Ghana, running a wholesale business Stormzy helped her establish there.

“Mum used to work bare jobs,” Stormzy explains on one of our days together, while tucking into a double lunch of lamb chops and sweet and sour chicken, with two rounds of egg fried rice and two Appletisers, at a fancy Thai restaurant near central London’s Oxford Street. “She was looking after all of us and working all these jobs. I remember her coming home, being back for like an hour. Putting the kettle on, making a corned beef sandwich, sitting in front of the telly. Trainers on, back out. Women are powerful. Both my big sisters didn’t take no shit either, and they used to protect me.” Today, a respect for women is evident in his work. For his recent “Big For Your Boots” video, he surrounded himself with strong women including Beats 1 radio anchor Julia Adenuga, singer Ray BLK, and TV and radio presenter Maya Jama, who’s also his long-term partner.

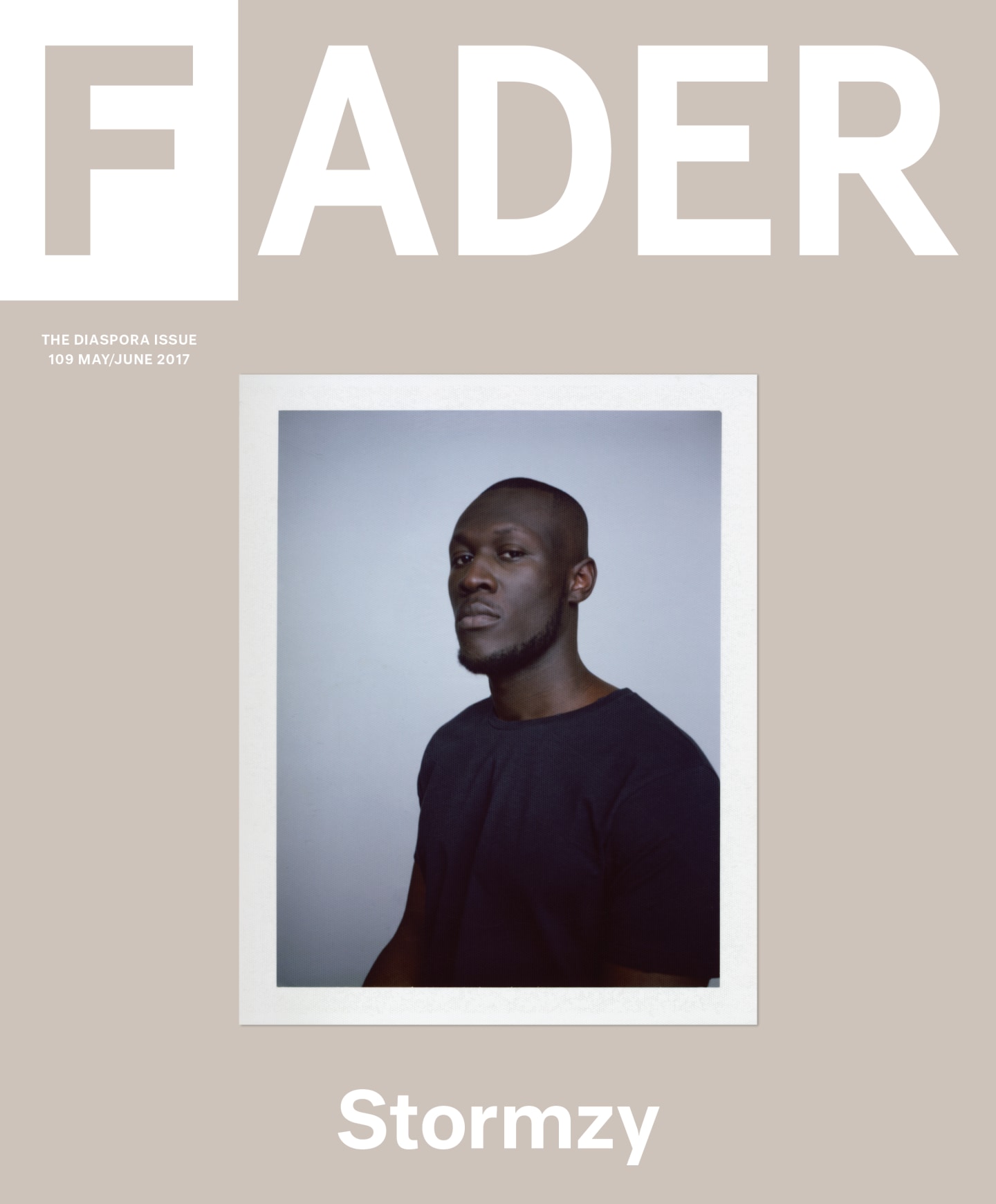

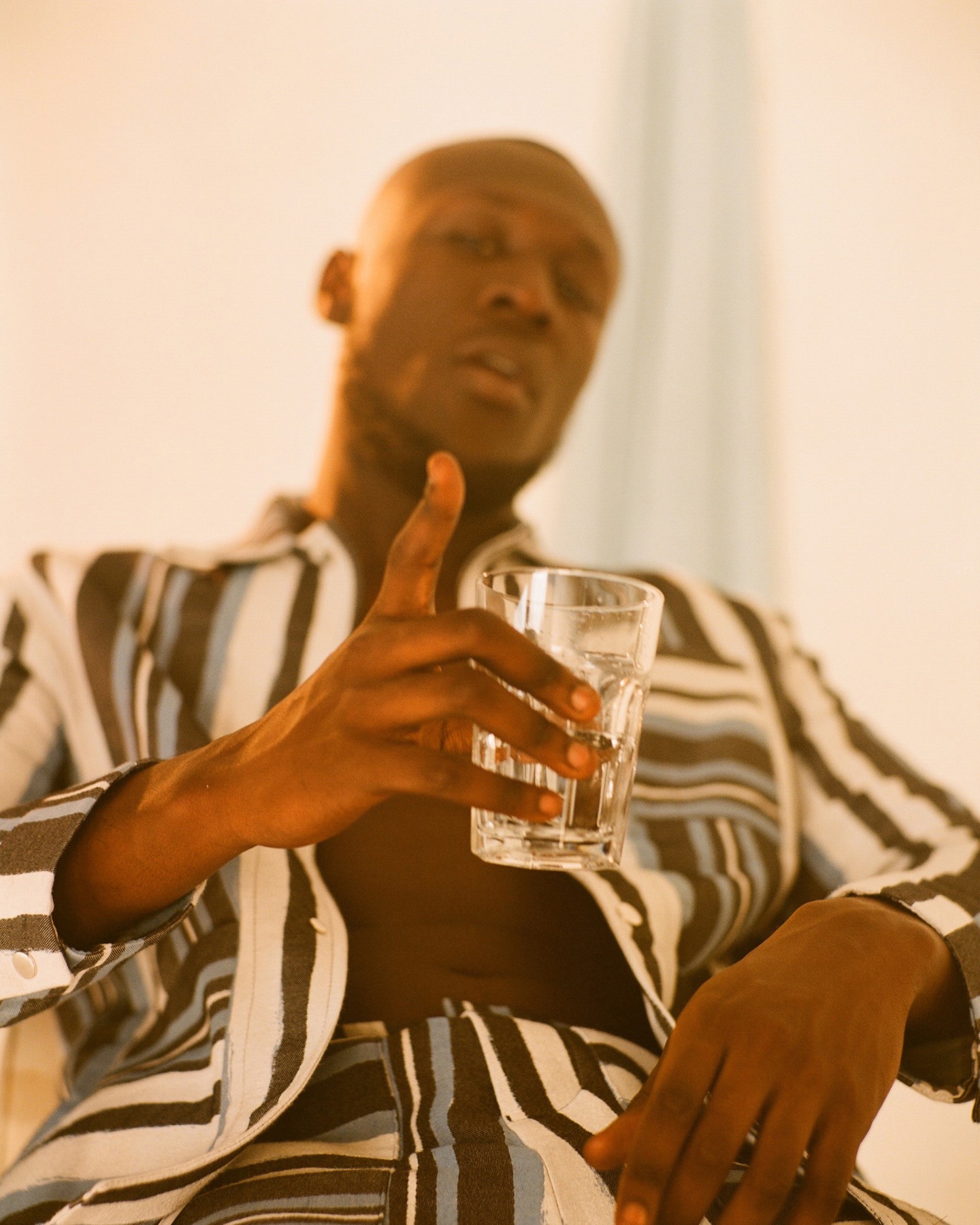

Agi & Sam jacket and pants.

Agi & Sam jacket and pants.

“I don’t wanna sound arrogant, but sometimes it’s cool to feel like that. That you deserve something.”

Stormzy’s father, a cab driver, was not present throughout his childhood. 2017’s “Lay Me Bare” details a recent encounter between the MC and his dad, in which the older man asked his now-famous son for a new car. “When you hear this, I hope you feel ashamed,” Stormzy spits venomously. “Because we were broke, like what the fuck?/ Mum did well to hold us up.”

According to statistics released by the Metropolitan Police in 2016, Croydon has one of the highest rates of youth violence in London. Stormzy remembers the kids he grew up alongside “worrying about getting stabbed or shot at.” He saw street life entangle “kind people,” and as a teenager, had his own short-lived stint as a small-time drug dealer. But for as long as he can remember, his life was anchored by MCing. 24-year-old friend Adrian Thomas, a.k.a. Rimes, met Stormzy at the age of 11 in secondary school and remembers taking him to a local youth club named Rap Academy, where Stormzy quickly gained a reputation as the best. “You just used to spit when you spit,” Stormzy remembers. “Youth clubs, the block, outside a chicken shop.” He would share his location via Blackberry Messenger, and local kids would show up to watch him freestyle.

Stormzy adored school. His favorite subject was English Literature; he wrote poems and devoured novels. (He can still passionately describe scenes in British author Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses series.) His stellar grades put him on course to apply to Oxford or Cambridge. But at 17, he was expelled for a series of minor transgressions, like talking back to his teachers. He briefly enrolled in a different college, only to walk out of an English Lit exam and never come back the following year. “Looking back, it was a bit cocky,” he says. “Like, I’m smart, I’ve got faith in myself.”

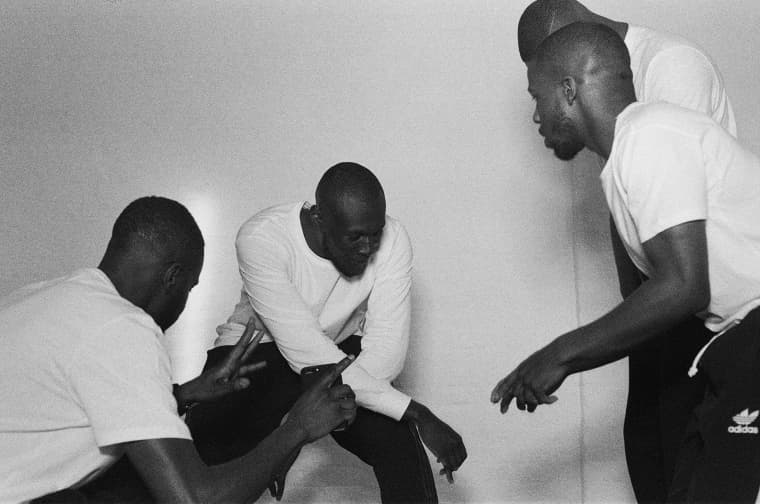

Stormzy: Urban Outfitters jacket, Carhartt pants. Tobe (left): SCRT jacket. Rimes (right): COS jacket.

Stormzy: Urban Outfitters jacket, Carhartt pants. Tobe (left): SCRT jacket. Rimes (right): COS jacket.

After briefly working in a warehouse, he landed a prestigious apprenticeship with the engineering firm Doosan Babcock in 2012, which required him to move to the middle of the country for eight months. He then went to work in an oil refinery in the port city of Southampton. The work was easy to him but he was dispassionate about it, and he dedicated every spare moment to music. When he had a week off from training in 2013, he used it to make a mixtape that he titled 168, after the number of hours in a week.

Stormzy’s ambition was piqued when he saw South London rap duo Krept & Konan win a MOBO Award for Best Newcomer in October 2013. “I went to school with Krept. Konan knows my sister from years ago,” he says. “I’m looking at them and thinking, What? Why can’t I spit and get a MOBO?” He quit his job a few months afterward.

The gamble paid off. During the week we spend together, Stormzy has the No. 1 album in the U.K. with Gang Signs & Prayer, which was released on his own label #MERKY, distributed by ADA of Warner Music Group. It sold over 65,000 copies in the U.K. its first week, and set a new British record for the most first-week streams of a No. 1 album. “I just felt I deserved it,” Stormzy shrugs. “I don’t wanna sound arrogant, but sometimes it’s cool to feel like that. That you deserve something.”

To see an independent grime album reach No. 1 for the first time is a totemic moment not only for Stormzy, but for the genre as a whole. “I’ve never understood this whole thing of there being this elite force in British music, but on the side is grime and rap,” Stormzy says, indignantly. “There’s at least five or six artists in that elite of American music. Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, Kanye West, and Jay Z will be there. In this country, it’s not like that. I just question shit. I ask, Why can’t I get played on that radio station? Oh, they can only play it in the evening. But there’s a clean version, why can’t they do daytime? They might say something about the tempo of the song, or the feel of the song. So when I’m getting in the charts, it’s [so I can] break all the walls down, and say, ‘OK, what are you gonna say now? Why can’t you play me?’”

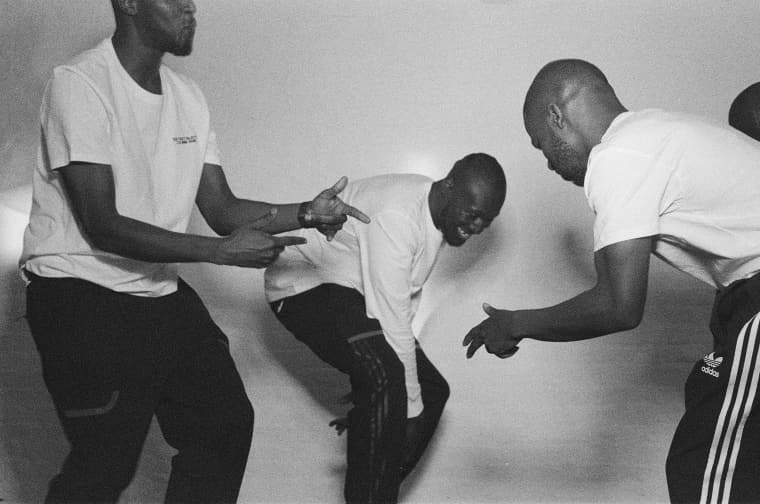

From left: A.P.C. T-shirt, Acne T-shirt, Urban Outfitters shirt and T-shirt, adidas sweatpants and sneakers.

From left: A.P.C. T-shirt, Acne T-shirt, Urban Outfitters shirt and T-shirt, adidas sweatpants and sneakers.

For many longtime grime fans, Stormzy’s mainstream success is a hopeful sign that times are changing. The older generation of MCs who came before him are watching his trajectory with pride. Reached by email, Skepta wrote, “Three years ago I met Storm, and I told him it was his world, his vision, and that he was gonna be exactly who he says, regardless of validation from anybody. He has really shown people how to stick to the plan.” Later, in an artist lounge at the BBC’s Maida Vale studios, British rapper Wretch 32 explained the pleasure of his success succinctly: “The special thing about Stormzy is that the next generation can see a ‘Yes.’ Whereas before, even my generation, they always saw a ‘No.’”

Though its muted grey decor is unassuming, Maida Vale is a historical landmark of British music. The Beatles have recorded in the building, and electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram established her Radiophonic Workshop there. Today, its corridors are teeming with backing singers, session musicians, and producers, all drifting in and out of a Live Lounge session that Stormzy is recording for BBC Radio 1Xtra the sister station of Radio 1.

In a control room packed with managers, publicists, and sound engineers, I can see 22-year-old singer-songwriter MNEK through one-way glass. He’s dressed in head-to-toe camouflage with gold-painted nails, practicing his ad-libs in the studio. MNEK, Stormzy, and their band — including a choir of eight — are waiting to begin a performance of Gang Signs & Prayer’s climactic gospel anthem, “Blinded By Your Grace Part II.” Stormzy plays both entertainer and focused conductor, giving notes to his band. “If I could sing, I’d be doing that shit all day,” he says to MNEK. “I’d talk like” — he starts crooning into his mic — “Wagwaaaan, you coool?”

An engineer asks if anybody has any jokes, to pass the time.

“I do,” Stormzy says, immediately. After theatrically thinking for a moment, he says into his mic, “What did MNEK say after a policeman sprayed him with CS gas?”

Both rooms fall nervously silent.

“I’m blinded by your mace,” Stormzy grins, to the room’s collective groaning and hysteria.

In 2014, it was the hilarity of freestyles like “Shut Up” and his “WickedSkengman” series — and his 2015 video “Know Me From,” which starred his mum — that helped to propel Stormzy to a national audience. He first learned to weave humor into his bars from a Croydon DJ and MC named Carl Beatson-Asiedu, a.k.a. Charmz, who took Stormzy under his wing as a teenage MC. “He would cuss your mum, cuss your shoes, talk about your girl,” Stormzy remembers. “I used to emulate him.” Beatson-Asiedu, tragically, was murdered in 2009.

That humor has also made Stormzy an unlikely figurehead of “lad culture.” Something like the British equivalent of a frat bro, a lad is a young man who drinks Jägerbombs, follows soccer religiously, and reads about other lads on sites like UniLad and LADbible. Stormzy’s appeal to this demographic could be down to his approachability: back in 2015, when he appeared on the sports commentary TV show Soccer AM, Stormzy tweeted: “Can someone record Soccer AM for me I’ll come round and watch it later dead serious.” He made good on his promise, turning up at the home of two random fans with a freshly rolled spliff. He’s also adept at the cutting comeback. When a tone-policing tweeter recently asked him, “Have you ever thought of projecting a warm, friendly...image?” he replied, “No not really? Have you ever thought of fucking off?”

Stormzy traces this part of his persona to the time he spent living with 17 white teenagers from different parts of the U.K. while working with Doosan Babcock. At first, Stormzy isolated himself from them, eating dinner alone in his room every night. “I remember them calling each other ‘cunts’ and play-fighting. I was thinking, Are these lot mad? Where I’ve grown up, you only laugh in the comfort of your home. If man sees you busting jokes on the corner, you’re moist.” Slowly, his coursemates convinced him to start coming to the pub with them, and Stormzy let his guard down. “Now I realize, all those things are backwards. You don’t have to be a fucking bad boy 100 percent of the day. It’s tiring. Life is much more fun when you can just be yourself.”

Rimes, Tobe, Stormzy, and Flipz

Rimes, Tobe, Stormzy, and Flipz

“Young black brothers that have grown up in similar situations to me, they feel like, ‘This is it.’ That’s not right.”

Two weeks before the release of his album, in February, Stormzy moved into an apartment in a rich, largely white borough in west London. In the early hours of Valentine’s Day, he returned from the ELLE Style Awards and went to bed. A neighbor, seeing Stormzy enter his own apartment, reported a burglary, and Stormzy awoke around 5 a.m. to the sound of the police battering down his front door. The following morning, he tweeted a picture of the damage done by the police. The photo was printed that night on the front of daily London newspaper the Evening Standard.

To Stormzy, the intense reaction of the public to his tweet was more revealing than the incident itself. “People were asking, ‘You must be shocked?’” he remembers. “I’m thinking, Bruv, I’m not fucking shocked. As a black youth, nothing has changed. If someone doesn’t know I’m Stormzy, I’m a 6’5” dark-skinned brother in an all-black tracksuit with a gold tooth and a deep voice. If people have views already, I’m gonna fit that view.” When he posted the photo of his smashed front door to his WhatsApp group chat, none of his black friends were surprised; they offered up pictures of their own battered front doors, as a comparison. “Everybody in the hood knows, everybody in the culture knows,” he says. “But it’s good that now the world can see.”

Following the news uproar, Stormzy appeared on U.K. comedy panel show The Last Leg, where he brushed off a question about whether the incident had a “racial undertone.” If he could do the show again, he tells me, he would have just replied “Yes.” The whole episode has made him consider, more deeply, the uniqueness of his position as a British celebrity. “A lot of places, I may be one of the few minorities in the building, or on the panel, or on the stage,” he explains. “I’m gonna be facing a lot more of these situations. In this country, there are not enough black actors or musicians. So when someone gets there, you’ve got to be the voice that calls out the bullshit.”

On several Gang Signs & Prayer tracks, Stormzy broaches the subject of depression with an intimate intensity. Where he comes from, he says, mental health problems are both widespread and unacknowledged. “It’s a mixture of smoking lots of skunk weed and what we see and go through. There’s people around me who just have dark clouds of energy all the time. That was me when I was younger: paranoid. I used to think all my friends hated me, that someone was going to rob me. In the hood, you don’t even clock it. It’s the norm.” It’s murky, complicated, and not something he is completely past. “I don’t feel like I’m totally through it,” he admits of his depression. “I’m in a weird place. I linger over it.”

In the living room of his west London home, light floods in through French windows that take up an entire wall. Aside from its upmarket, leafy vibe, it feels like any flat a 23-year-old just moved into: a flat screen TV and PlayStation 4 are among the few things unpacked, and pull-up bars have been installed in the garden. Small clues give away who really lives here: MOBO and Rated Awards haphazardly adorn the glass shelves; a framed, signed Manchester United T-shirt waits to be hung on the wall; an all-access pass to Kehlani’s London show lies among grinders and skins on the glossy black dining table.

Topman T-shirt.

Topman T-shirt.

Stormzy doesn’t feel like going outside today. Wherever he goes in London these days, he is recognized and mobbed by fans. Though he sought out crowds as a teenager, as a man he’s comfortable being alone.

Dressed all in black, he sits hunched in his chair, his height almost diminished. He uses scissors to snip a perfect rectangle from an adidas cardboard tag, which he then rolls into an impeccably neat roach. Describing his strange “limbo” feeling, post-No. 1, he says, “I’m on a high. You get a blast of it for a couple days. And when it all settles…The expectation levels are different. There’s more eyes.”

A few times throughout the days I spend with Stormzy, I see this more reflective and solemn side of him emerge. At one point, unexpectedly, he tells me that he is the kind of person who’s incredibly happy to sit in silence; that sometimes, he and his closest friends will easily hang out without speaking to one another. It’s this space for contemplation that gives Stormzy’s work its depth. His nuanced sense of balance is palpable on Gang Signs & Prayer, a record that contains delicate odes to his mum and somber reflections on racist media alongside the whiplash 140BPM of traditional grime.

Sometimes, Stormzy is the joker who can go to the park, record a freestyle with his friends, and use a funny social media campaign to get it onto the charts — as he did with “Shut Up.” But as he showed on the set of “Cold,” his current level of success also comes from his ability to step back, and to view the wider picture.

Later, as the sky darkens, Stormzy walks into the central London department store Selfridges through a back entrance with his publicist, his friend Flipz, and a personal shopper. We are assigned a security detail, to prevent anyone from asking for pictures as Stormzy browses Prada and Louis Vuitton racks. Even so, there’s a constant ripple of energy as roughly every other person we pass reacts visibly to his presence.

One thirtysomething man, in an expensive blue suit and scarf, strides right up to Stormzy and asks for a photo with the casual tone of an old friend. When Stormzy politely declines, the man’s face falls. “Come on,” he groans. Stormzy frowns, uncomfortable. “Sometimes,” he tells the guy, “I just want to shop and chill.”

But when kids approach him more timidly, Stormzy’s reaction is mellow. At one point, a group of schoolchildren suddenly materialize behind him, dumbstruck with excitement and following him like ducklings. Some take photos of him through the clothing rails. He smiles at them, and, as we float around the store, passes out the occasional nod or handshake.

Stormzy might have an audience of millions now, but he has a particular soft spot for his youngest listeners. Later, back at home, he compares being a celebrity to being a time traveler, like out of Back to the Future , returned to tell black working-class children that breaking the glass ceiling is possible. “People I’ve grown up with have literally given up before they’re flipping 21,” he says. “Young black brothers that have grown up in similar situations to me, they feel like, ‘This is it.’ That’s not right.”

He not only plans to empower the next generation of black artists, but to build material pathways to help them succeed in the industry. “Black music in the U.K. — we have always been incredible musicians, but [on] the business side of things we have never had an incredible infrastructure. So that’s what I plan to build, with #MERKY. What we do now is we make record labels. We make production companies, media agencies. Revolutionary shit.”

Stormzy acknowledges the structural barriers that have hindered POC artists for generations — but he refuses to limit his ambition. He speaks with the same calm authority he had on the shoot, where he pushed those around him to think bigger, to want more. “I’m an optimist. We’re at a point where all the people before us, all the musicians, all the politicians, all the black leaders, all the black actors, have knocked down enough doors.”

“Think about it — when does the door knocking stop? There has to come a time when you’re in the fucking building.”

Groomer: Maria Asadi. Agency: WE Folk. Location: Spring Studio.

Photo Assistants: Fran Rois and Eva Abelling

Stylist Assistant: Bongeka Dube