The Genius Of Miles Davis

In this story from our June 2005 Photo Issue, percussionist and former band member Mtume reflects on the jazz legend’s complicated legacy.

Mtume, known for his ten-finger, tabla-influenced method of playing the congas, was a percussionist with Miles Davis's band from 1971 to 1976, appearing on On The Corner, Dark Magus, Agharta, and others. In the '80s he charted hits like "Juicy Fruit" and "You, Me And He" with his group (also called Mtume), and teamed up with Reggie Lucas — a former bandmate in the Miles group — to write and produce for artists like Levert and Roy Ayers. Now retired from playing, Mtume is a community activist and radio talk show host for Kiss FM in New Jersey.

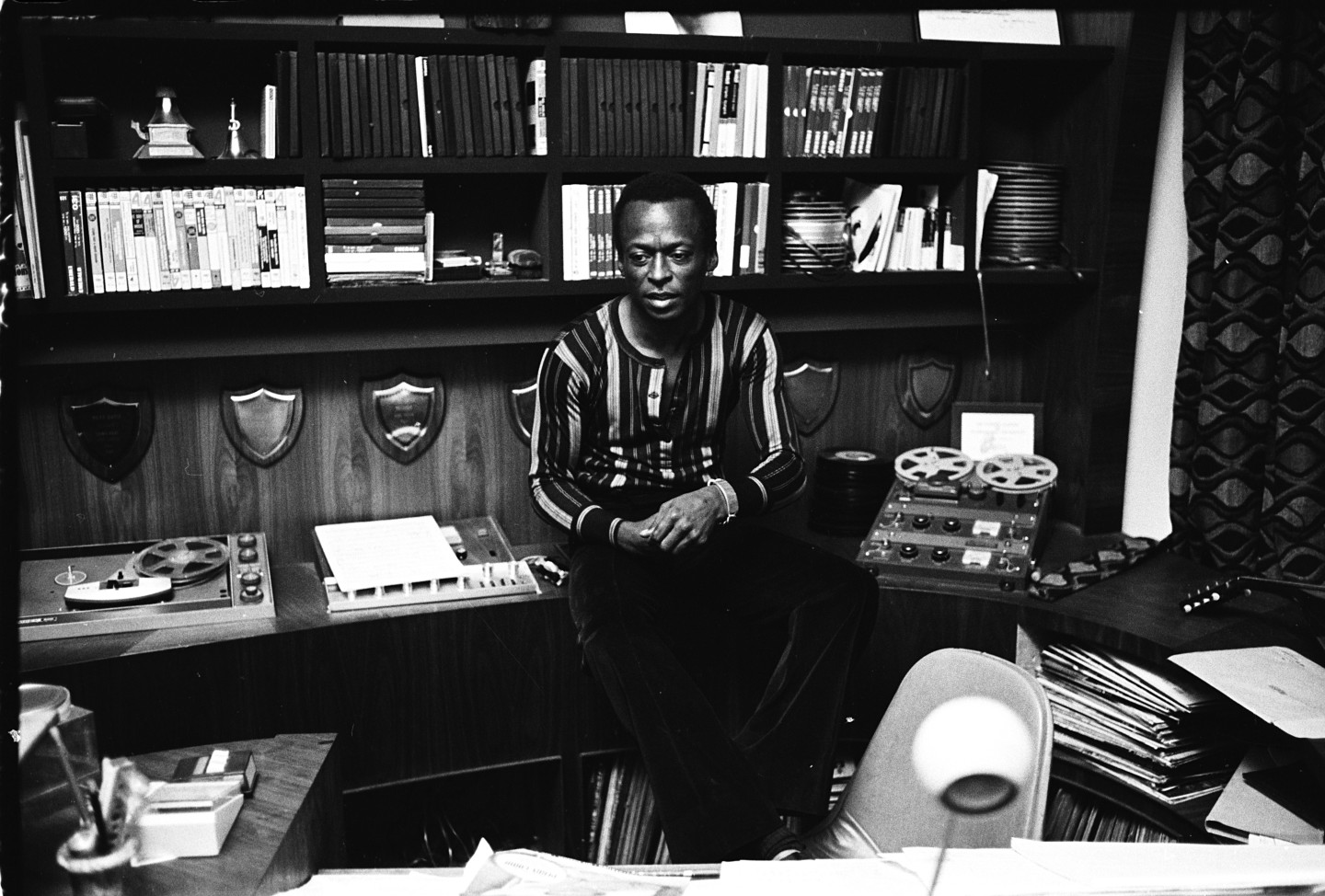

Miles and I used to talk all the time and one time, we went to this Indian restaurant on 125th street. We talked about a lot of different things and at the end of the conversation he said, "Well what do you think?" I was like, "About what?" He said, "We've been sitting here for two hours. Did you hear the music?" As you and I both know, in a restaurant the music is background, but he asked what struck me about it most. I said the tablas and sitar. He said that's what we're getting into next. That next album was On The Corner.

Miles decided to delve into electronic music, and it started with Miles In The Sky, when he used an electric piano and had George Benson on a couple of cuts. From there, he went to Filles De Kilimanjaro and In A Silent Way — you saw it coming. When Bitches Brew hit, all hell broke loose. Lots of other bands were breaking off from [his band] — Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return To Forever. But rather than go with them into fusion, which was mostly made up of exercises in complexity just for your head, Miles said fuck that — let's explore the funk. Let's explore one groove and ask, How long can we keep it interesting? That's the tunnel we were forging ahead in: finding the complexity of simplicity. The beginning was On The Corner; by the time you get to Black Magus, you hear it — this is totally improvisational funk.

He had done everything he could do in the realm of "jazz." The fact is, Miles came to grips with one thing: if you are going to change the music, you have to have access to new sounds. Jazz cats just didn't have it. In 1971, when I stepped on that stage, he was playing wa-wa with the trumpet — you still haven't seen that in 2005. Most of his players came to his band because of recommendations from other great musicians. He started introducing new members, and we'd introduce him to other musicians he had never been around.

Miles was talking to Sly Stone, trying to hook something up. Hendrix died right after Isle of Wight [in September of 1970] and Miles said he wouldn't have really have played with Jimi since Jimi had his own thing going on, but they were going to exchange ideas about musicians. Jimi wanted to move toward jazz, but there was never a conversation about them playing [together]. But with Sly, it was a different story. Before On The Corner, we were getting in tune with a lot of our influences like P-Funk and stuff like that. Back in like '89 Sly lived with me for seven months and we had lots of conversations. He said that Miles was ready, but Sly was scared and said he wasn't ready, so the conversation petered off — Sly was intimidated.

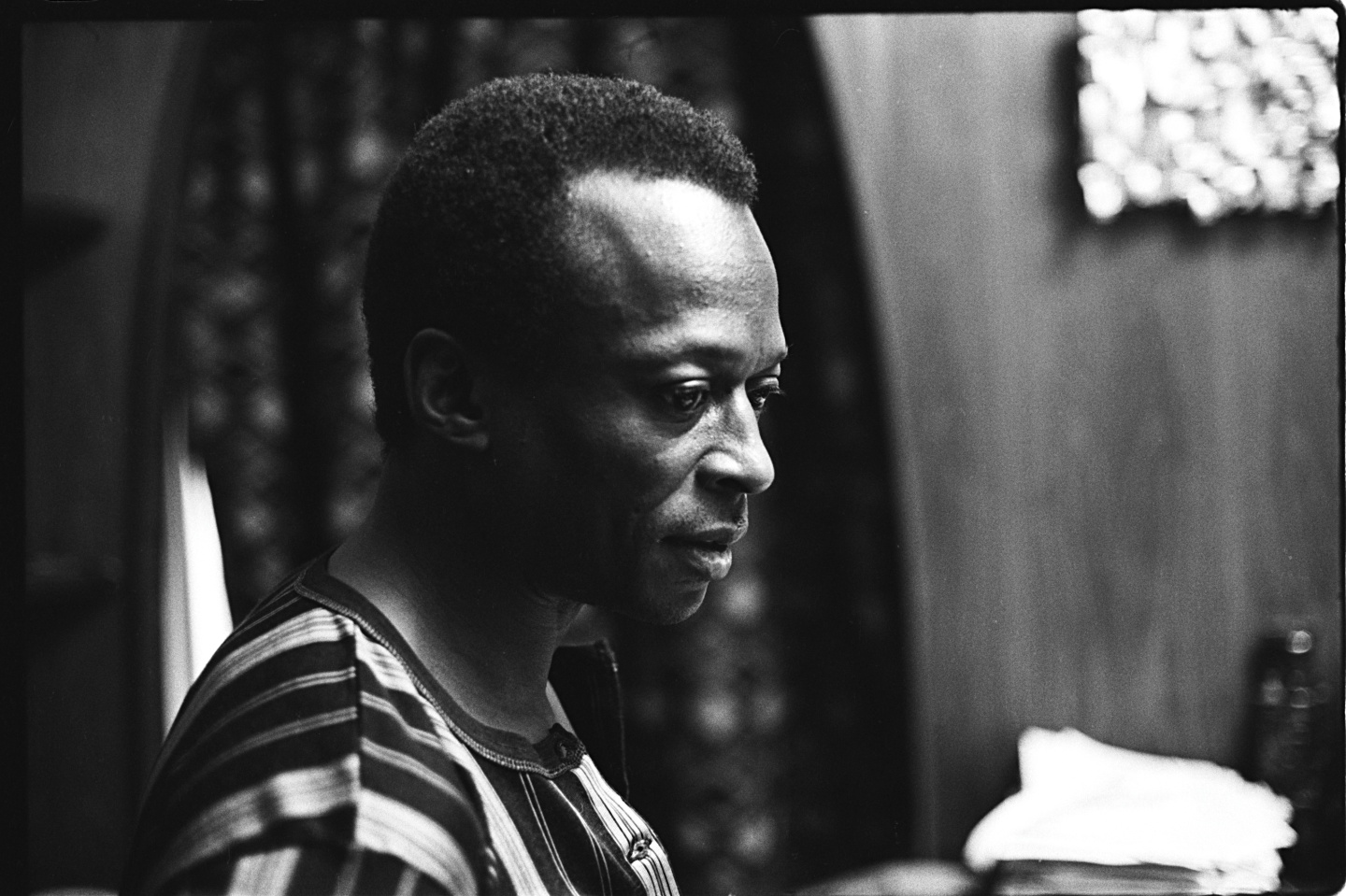

All the guys will tell you [playing with Miles] was amazing and it was — you were on stage with a true master. But when I stepped on the stage with Miles for the first time I was in awe of my responsibility to all those great cats who had stood up there with him before me. I came out of a jazz family. My father and my uncles — the Heath brothers — Jimmy, Percy, and Albert — all played with Miles. So I grew up with it. As a kid, man, all that shit was around the house. I used to listen to Milestones because I dug the cover — him with that slick shirt. In 1971 I had already played with Sonny Rollins, McCoy Tyner. I had recorded with Herbie Hancock. Gato Barbieri. But for me, brother, I had a responsibility to play as well as I could and to be as honest with the music as I could, not just because of Miles, but because I was into Coltrane and those cats that came through that I learned from. For me it was a rite of passage into the history of bebop. Miles Davis was the vessel through which the blood of those cats — Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Bird — was channeled. That's how I felt. I had to be responsible to the school that they came from, and it put a check on me to play as best I could. To play honestly, and to surrender to the music. When Miles changed his music, he changed his band, so it was a requirement — you had to surrender your ego.

At the time, there was a big argument in the jazz community: acoustic versus electronic. Lots of jazz cats were angry about Miles's choices — they felt they'd been abandoned. But you cannot create new music without access to new sounds, and jazz at that time suffered from technical exhaustion. There's a point with any instrument where there is nothing new to be played. With the saxophone you had Bird and Trane, and you can't get any more than that. The instruments themselves became exhausted and the only way to expand that was to be electronic. People say acoustic music is natural. I said what the fuck is natural about a saxophone? It's all about technology. A lot of critics didn't get it then, and they still complain about when electronics when musicians work on their computers. Miles challenged that and became the whipping boy for that. He threw the baby out with the bathwater.

On The Corner was the first time the critics said we were awful, redundant, but that was also the first time we started to see young people at our shows. Miles and I used to talk late at night — 'cause he was an insomniac and so am I — and one night he said, "Look, black people aren't coming to hear the music. I gotta make a change." That was the conversation before On The Corner — the record that was the exploration of James Brown and the funk. He was concerned about young black kids not coming to the shows. If you can find the LP to On The Corner, look at the cover. He had pictures of all these black characters — the pimp, the Panther, the prostitute. There's a white band in there and if you look at the drummer's foot, it says "Foot Foolers." That was Miles saying, "I really got the funk." He put the critics to work; he didn't want to put anyone's name on the LP, so the critics wouldn't even know whose music it was.

With On The Corner, we were getting more and more black people and that pleased us. Miles had really decided to embrace his background; his grandfather was a Garveyite and also the bookkeeper for all the lazy white businessmen in East St. Louis. Miles's statements kept getting bolder. Just before he died, in his last interview in Jet, they asked him, "If you had 15 minutes left to live, what would you want to spend those 15 minutes doing?" You'd think Miles the player would say some shit about chicks, but no — he said "I'd like to spend the last 15 minutes of my life with my hands around a white man's neck." Later Dave Liebman and Keith Jarrett — two white guys in the band — did interviews for a documentary on Miles that was on DVD. When the white guys talked about the politics of the band it all got attributed to the leader, but we were all renegades and the music was a renegade. I mean, Miles was always the critic's darling — they'd say "Oooh-oh-oh" to everything. But because he challenged the critics to try to define what it was that we were playing, their idea was to marginalize Miles for the way he delved into experimental black music and because of the look and the attitude of the band.

You need to see the footage of the shows to understand the look that we had. Miles had be-ass red, black, and green speaker covers — a wall of speakers. You know what that meant, we were not giving a fuck about no critics. We had bad nights, but no one needs a critic to tell them that, or it was a great night. We didn't care [what critics thought] and we told them, "We don't care about you." You gotta remember — before that, critics played a big role in how cats made music. Here comes Miles and he's being urged to go backwards, but now he's got this band of guys who don't care what critics think. That enraged them. You needed that attitude. One time MIles said, "It's 20 percent talent, 80 percent heart. You can find cats who can play the notes, but to change music, you gotta have the heart." His band didn't care. A lot of guys in the band didn't know who jazz critics were anyways. The critics got insulted. I told them, "You don' even know what we're doing, so how can I respect your commentary?" I never had a conversation ever with any editor from any magazine and we accomplished a hell of a lot after that.

It was a creation of a new mantra and a new way of hearing the music. The challenge was to make what you're doing feel like it ain't worked out. But it was absolutely worked out. Some nights it's like walking on eggshells, 'cause you can't crack 'em. Some nights you might crack a couple of eggs — you can play two or three hours, brother, and in those two or three hours you have a few moments that are the most ecstatic points in your life. But you gotta work to get there.