This 2001 Story Of The Strokes’ Rise To Fame Is A Rock & Roll Time Capsule

Online for the first time, this profile of the now-iconic New York rock band—their very first cover story—is a snapshot of the hype around them.

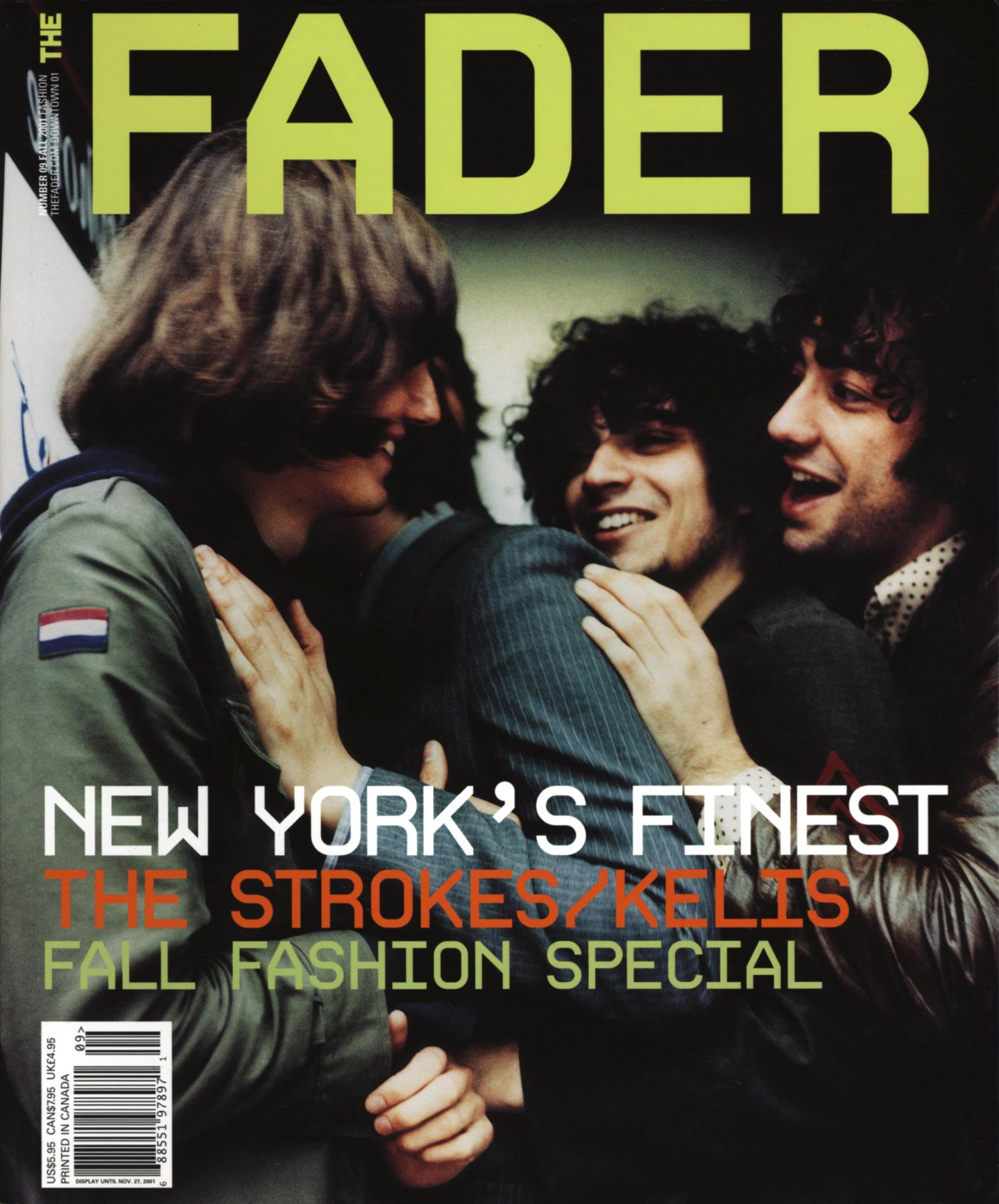

In 2001, for The FADER's 9th issue, writer Eric Ducker tagged along with The Strokes on tour in London for their first-ever cover story.

Fuck Cameron Crowe. First, fuck him for creating Say Anything’s Lloyd Dobler, the model that produced an idealized standard that no American heterosexual male born after 1970 can attain. Second, fuck him for creating a mythology that acquaintances, relatives and editors confuse with what it’s actually like for a young journalist to go on tour with a rock band, despite the widely accepted fact that movies are not reality.

Actually, Crowe may have confused some rock bands too, for when I first meet New York City band the Strokes, as they drink beer on the roof of London’s Soho House, lead-singer Julian Casablancas says to me, “You’re 22? You look older than that. When I heard you were 22 I was expecting a little guy being like [adopts a high-pitched, naïve tone], ‘Hey guys. What’s up?’” This is especially funny because we are, in fact, the same age and because I am slightly older than the rest of the band (bassist Nikolai Fraiture recently turned 22, lead guitarist Albert Hammond Jr. and drummer Fabrizio Moretti are 21 and rhythm guitarist Nick Valensi is 20).

Truthfully, there were no tripping on acid, jumping into swimming pools, Almost Famous moments during my four and a half days with the band during the end of the United Kingdom leg of their summer tour, except for later that first night when their 23-year-old manager Ryan Gentles gave me the Russell Hammond line, “Just make them look cool.” I told him that they don’t need any help looking cool. Then he corrected himself and said, “I just mean write it how it actually is.”

If this was a story hyping the Strokes I would call it “Standing On The Verge Of Getting It On.”

If this was a story about the hype about the Strokes, I would (predictably) call it “Almost Famous.”

If I were feeling cheeky I would call it “Nearly Well-Known.”

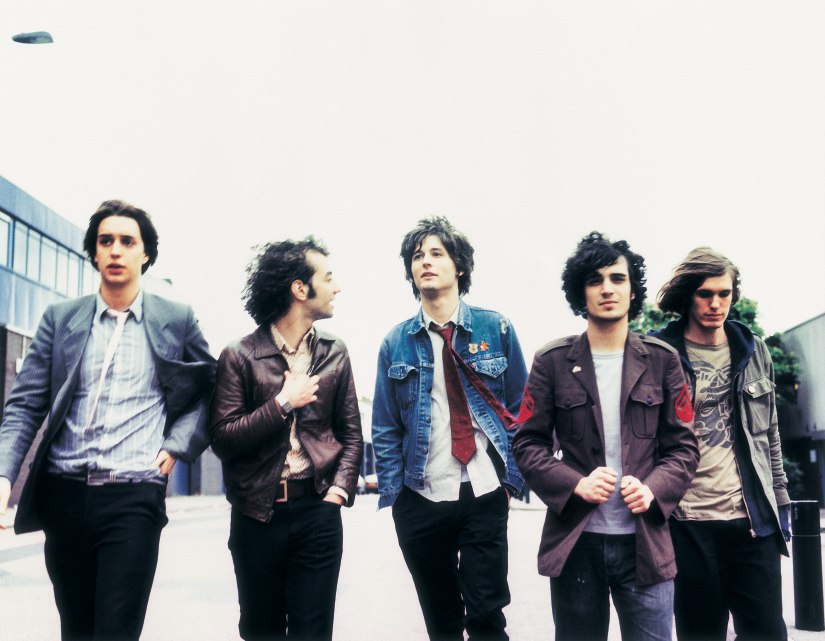

Following the fuzzy logic of phenom-based journalism, there are already more articles about the Strokes that cover them being hyped than there are ones that hype them. So in regards to the hype, I’ll say this: there are people who sing Velvet Underground lyrics (never the appropriate ones) along to the Strokes. There are also people who will tell you that they hate the band without hearing anything by them. Both of these responses are to be expected. In regards to hyping them, I’ll say this: without hearing any music, the FADER knew months ago we were going to feature the Strokes the second photographer Leslie Lyons showed us the publicity photo she took of them.

Five minutes after I meet Casablancas we’re out on the street and he’s got his arms around me and is whispering into my ear, in a tone somewhere between sinister and conspiratorial, “Welcome… welcome.” Then he gives me the rap about Mr. Fly-On-The-Wall-Journalist who hangs out for a couple days and thinks he knows how it is. It’s tough to take Casablancas entirely seriously, because I’m not sure if he is taking himself seriously. Later at Trash, the rock night at a club called The End, it’s a parade of white England’s former fashion trends. There are boys with vintage urban cowboy shirts, boys with mohawks, boys with paper fans who are part of the new wave of retro-foppishness, boys with thick-rimmed indie glasses and flight bags, boys in Idlewild. This is the Strokes’ fan base, so the band doesn’t get recognized or approached much. Instead they look like boys who look like the Strokes.

“We have no intention of being the fashion kings they’re trying to make us out to be.”—Fabrizio Moretti, The Strokes

“I’m in the middle of an emergency. Can I call you back? Actually, I lost your number, can you call me back? I’m at a medical clinic.”

This was when I was still back in America, I had called Gentles on his cell phone to arrange the first meeting between band and journalist. Rock star medical emergencies usually bring three options to mind: (a) over-dose (b) van accident (c) drunken fight with band members or other parties.

Later that day I find out that the emergency is that drummer Moretti broke his left hand after a fall while exiting the band’s van. Now he’s not only unable to play for the next six weeks, but also needs assistance putting on his coat, buttering bread and opening beer bottles. And no, he was not drunk at the time. Just a week and a half into a tour that will last all summer and cover 12 countries, the band cancelled showed in Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield and Birmingham, and nearly postponed the entire venture until Moretti recovered. Luckily, relief came in the form of Matt Romano, the drummer in Gentles’ former band the Selzers and a friend of the Strokes. Romano’s plans for the summer entailed working part-time at a record store before he got the call to sit in with the band being treated like the hottest shit since shit came hot.

Assimilating yourself into a group in just 36 hours is hard enough, but Romano replacing Moretti has extra clauses. None of the Strokes have ever seriously worked with another drummer–the band evolved out of classmates Casablancas, Moretti and Valensi playing music together in their mid-teens–and those within and close to the band describe Moretti’s drumming as “a gorilla on cocaine” and “Superman meets the Green Lantern on speed.” It’s a tough job to fill if you’re not a primate or a superhero with a drug problem.

“Right now I’m doing what I’ve wanted to do since I was a kid—a seven-year-old kid listening to Guns N’ Roses saying to myself, ‘I want to play music.’”—Nick Valensi, The Strokes

When you’re in the middle of it, it’s tough to keep perspective on how big they are. And while they easily sold out every show of their first headlining UK club tour, when they play the Leeds and Reading Festivals at the end of August, it will be on the second stage, billed below Evan Dando.

Surprise! The Strokes actually aren’t the bad boys they’ve been made out to be. Well, they are no badder than most of the boys in their early twenties that you know. They’ve got the usual vices–drinking and girls–but you’d be disappointed if they didn’t and they’re far from out of control. Most of the time, the five have their paws all over each other, and those they consider part of their extended family. It’s a non-stop incestual hug and grope fest. This isn’t to say that the Strokes are pansies. They don’t start shit, but they don’t take it either. Maybe it’s the haircuts that makes everyone think that they’re bad. Maybe it’s because they wear secondhand jackets. Or maybe it’s because Valensi owns a pair of “I ❤️ Jesus” socks. No, it’s probably not the “I ❤️ Jesus” socks.

Anyway, that’s just fashion, not an explanation for a disposition. But the Strokes will always be tied to what they wear, whether they like it or not. NME ran an article on the Strokes’ influence on clothing designers’ new lines and even gave advice on “How To Look Like The Strokes.” The answer: go to a thrift store in the East Village. Similarly, not only is it how they look that leads to the assumption that they are bad, but every embarrassing or stupid thing they ever do is exaggerated to take on lifestyle-defining significance. Every time one of them takes a piss in public or gets drunk and knocks into a journalist at a show it adds to their rep. In regards to fashion and their attitude, Moretti responds, “A lot of people try to make us out as this half-fashionable, half-pissed-off band. For the record, we are very fun-loving guys. We have no intention of being the fashion kings they’re trying to make us out to be. We’re geeks that wear the clothes we’ve been wearing for the past five to ten years.”

It’s like they won an MTV contest for talented people: you and your four best friends get to travel the world with amps and per diems and refrigerators backstage filled with beer and whatever types of cheese you desire. Valensi says, “Right now I’m doing what I’ve wanted to do since I was a kid—a seven-year-old kid listening to Guns N’ Roses saying to myself, ‘I want to play music. I want to tour the world.’ If this wasn’t fun, I’d still be studying American Literature at Hunter College. Right now, this period of my life is the most fun I’ve ever had.” So is this the best summer ever? "So far. Fuckin’-A yeah. I mean Fab’s got a broken hand, that’s the only problem.”

“I just took a big ol’ shit,” says Moretti, dropping into the back bench of the van. “I took a big ol’ shit too,” adds Valensi taking a seat next to him. On the way from London to Colchester, a small town in Essex County, we review Gentles’ video footage of the trip so far. We watch the gig in Manchester, the last show Moretti played. The one he played with a broken hand. During “Take It Or Leave It,” the last song of the set, Moretti says, “I was so happy when we got to the last chorus. I was in so much pain.” The band sequestered themselves in rehearsal for the past day and a half, trying to acclimatize Romano to their pace (fuck jet lag, fuck being nauseous). On the ride, Romano listens to Is This It on his discman repeatedly. Fraiture assumes his normal spot riding shotgun, occasionally smacking the TV monitor when a hole in the road disrupts the connections. Valensi reads James Joyce’s Dubliners.

The van pulls into the venue at beer o’clock: already there to greet them is a group of kids in skinny ties and their dad’s old sweaters. Inside, the band sound checks and gets into an argument about the use of a barricade in front of the stage. Valensi and Casablancas are pro, Hammond is con. [Sample Dialogue–Casablancas: “Watching that shit in the van, it looked so stupid with that guy on stage dancing next to me like an idiot.” Hammond: “I thought it looked cool how you kept looking forward and didn’t even acknowledge that he was there.”] The band get progressively more wasted. When they run out of Bud backstage they petition the venue’s bar staff for some tall cans of Fosters and shots of Jack Daniels.

A schedule for the night has the Strokes playing from “10:45—?” but the Strokes don’t jam. Their set lasts roughly 36 minutes, the length of Is This It, and adheres to the order of the track listing. The Strokes don’t do covers, outtakes, encores or much banter besides introducing songs. The Strokes play Not Now Music (my term, definitely not theirs, and not necessarily one you should adopt or base your interest in the band on. Valensi stresses that anyone who wants to know about the band should “if not buy our record, tape it off a friend or come to a show and judge for themselves”). It is music rooted in the past (I’ll let other critics debate which Non-Commercial Yet Influential rock band it most sounds like), but it has the urgency and frustration that takes it back to the future. When I heard The Soft Bulletin by the Flaming Lips in 1999, I realized it sounded like how I imagined the Grateful Dead would sound, before I actually heard the Dead for the first time when I was 12. When I saw Badly Drawn Boy at the Fillmore it was how I imagined old Van Morrison shows to be: somewhere between parody and mystical shit from a family man who is obviously not well.

When watching the Strokes play clubs the obvious way to imagine it as one of those Non-Commercial-Yet-Influential bands playing CBGB or Max’s Kansas City or the Mercer Art Center where everyone in the crowd just came from an Andy Warhol opening and they’re all drunk on champagne and Debbie Harry is waiting tables and you can buy the first issue of Punk from Legs McNeil and you can’t tell if Patti Smith is flirting with you or just being weird and Lester Bangs is making a mess of himself and at the back table, Lou Reed is there. Lou Reed is always there.

But you know that’s bullshit. The Strokes know that’s bullshit. Because it could never have really been that way. That perfect. That contrived. Not everyone could have been beautiful and talented. The sound couldn’t have been good. All of that could never really be going on at the same time. Not everyone could have been there to smile for the downtown ‘78 family picture. And I don’t know if anyone ever threw their panties on stage back then, like someone does in Colchester. But if they did, I hope whoever was holding the mic did the same thing Casablancas does—give it a quick sniff before casting it aside.

“Why does someone else always look like the lead singer in the photos?”—Julian Casablancas, The Strokes

“Why does someone else always look like the lead singer in the photos?” says Casablancas as he, Valensi and Moretti review potential publicity photos for their US tour. He’s right. Someone else is always in the center, in focus. Yet he’s the one who writes the songs, the one who drafted Hammond and early childhood friend Fraiture into the group, the one who gets on Romano’s case the most during rehearsals. It’s his personality—witty, wary, yet with an honesty that can slip into cockiness—that has been generalized as the personality of the entire band. There are other aspects of the press that the Strokes still haven’t figured out. When Valensi says, “I’m interested in getting laid and doing drugs as much as the next guy, but we also have a really good work ethic,” he doesn’t realize the immediate journalistic impulse is to blow that up into a giant pullquote.

The London show is in Heaven, a spot that is usually a gay disco. The show yesterday in Colchester was in what used to be a church. Like they say, it takes all kinds. Tonight is the Strokes’ biggest show so far in what is sure to be a year of big shows. Supermodels and Pet Shop Boys are on the guest list. Tickets that originally sold for £8.50 are now being scalped for £100. The Strokes come through in the clutch. If you’ve ever seen a good rock show, I’ll spare you the details, but man, the Strokes are fun. You should see them, a mix of controlled mayhem and boogie-oogie-woogie. Backstage Hammond is introduced to Jack Rovner, the head of the Strokes’ label RCA, who has flown in for the show. Once Hammond realizes who he is, he gives him a hug and says, “Welcome to the family,” even though normal logic would have the exchange going the other way around.

Later at the after-party in Heaven’s Powder Room, two boys in denim jackets are trying to persuade the wait staff to take off the trance and put on the Stones, but they are told the club “only has gay music.” It’s packed with music journalists, the band’s tech crew, scenesters and autograph seekers. As per the orders of an unknown individual outside of the band’s management team, two club security guards follow Casablancas around the room all night. They’re not stoic Secret Service types (they drink and hit on girls like Casablancas does), but wherever he goes, they’re right behind him. (When told about it the next morning, Valensi says “Last night’s crowd was the nicest of the entire tour. We could have used bodyguards in Dublin, Glasgow, Manchester.”) Outside the main room that is a bit much for him, Moretti politely humors a blonde girl with a backless shirt who is on some Keanu shit in what she thinks is consoling him about his hand, telling “You’ve got the power. You’re the one.” But she’s drunk. Everyone’s drunk. Because the Strokes are an American band and when they come to your town, you’ve got to party down.

The platitude is: the Strokes are New York City. But have you been to New York lately? It’s filled with girls in tank tops with thin straps, or one strap, or no straps that have words like NAUGHTY or FLIRT bedazzles across the chest. And the girls are all biracial or European. It’s crazy. Actually, that’s an exaggeration. Nothing’s ever that simple. There also still disturbingly large roaches and old men who cook up and mainline during lunch hour in front of the West 4th subway stop. There are high school kids who pop Ritalin to study for math tests and can afford to buy Prada sneakers to wear just once to the prom. There are arty skaters who thing thug shit is the next move and every move to a new neighborhood comes down to a bar with cosmopolitans and a video store with a David Lynch section. And the Lower East Side, where the Strokes now live after leaving the Upper East Side where they were raised (except the LA-bred Hammond), still smells like garbage all summer.

So are they looking forward to coming back? Casablancas says, “If we were going back to New York now, I’d say ‘Thank God we’re going back to New York.’ But we’re going to all these countries I’ve never been to, so I’m still like mentally prepped for the ride. Do you know what’s going to be fucking really cool is that when we get back to New York, we’re going to have been around the fucking world. It’s going to be like, ‘Hey guys. I was here a few months and I’ve just been… around the world and back.”

The next morning (early afternoon in non-rock time), the Strokes pack up the van for their drive to Amsterdam. Everyone is almost over their hangovers or, in Casablancas’ case, is still wasted. Tour Manager Kevin O’Dwyer informs the group that at the Mallorca Festival in Spain next week they’ve gone from an unknown second stage act to THE BAND NOT TO MISS. To Fraiture’s surprise, Valensi calls shotgun, and as they discuss how it seems to be getting claimed earlier and earlier, Casablancas calls shotgun for Australia. The first joint of the day is rolled. Moretti, unable to effectively push Gentles because of his broken hand, repeatedly pelvic thrusts him and then the exchange turns into a recreation of the Steve Martin/Rick Moranis dance lesson scene from My Blue Heaven. Even the normally quiet Fraiture starts talking shit. And then they’re gone. A rock band in a van with a broken stereo, continuing their good-natured bad boy roadshow.