In The Zone With Hudson Mohawke

Cover Story: HudMo’s beats bring everyone together. But he’d rather just keep to himself.

“I fuckin hate this computer,” Ross Birchard grumbles, hunched over his laptop. It’s May of 2014, just hours before the producer known as Hudson Mohawke is set to take the stage at New York’s Webster Hall. Decked out in all white, frowning beneath giant glasses, he’s been running late all day, and the night’s setlist isn’t nearly in place.

Punctuality isn’t Ross’ strong suit, but in this instance his excuse is legit—he had to tear himself away from a recording session with Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin and Antony Hegarty for the latter’s forthcoming LP. Antony is also one of a few surprise guests tentatively planned for the night’s show, but there’s a catch: the British crooner doesn’t want to actually appear on stage and has instead requested to sing behind a screen. “I don’t want the spot-light to be on me neither!” Ross exclaims, with a measure of sympathy.

The producer’s unlikely kinship with the trembly-voiced folk singer and composer is only one of the many fascinating twists and turns that his career has taken over the past six years: as Hudson Mohawke, the 29-year-old has accomplished a lot. He’s made a name as one of the leading figures in the Glasgow beat scene, accidentally invented an entire subgenre of electronic music—“trap,” the aggressive strain of EDM that borrows its name and sound from ’90s Southern hip-hop—produced for the likes of Pusha T and Drake, and ascended into Kanye West’s creative inner circle. Despite these considerable achievements, he strikes you first and foremost with his reserve, less like a big-shot producer-to-the-stars than an electronics-store employee who you’d ask to fix your smartphone.

In Webster’s upstairs green room, Ross parks himself on a leather couch, lights up a Marlboro, and throws on headphones to put the finishing touches on tonight’s set. When he’s in the zone like this, his replies to those around him are delayed or, on rare occasion, nonexistent. His attention breaks for the first time when he ruffles through a bag, searching in vain for a USB stick “with some really important shit on it.” Later, he looks up when the local rapper Bodega Bamz, another of the night’s surprise guests, rolls through. “Is Travis here yet?” Bamz asks, referring to the Houston rap auteur Travi$ Scott, who completes the night’s roster of supporting players. (Björk and Q-Tip are rumored to drop by, but don’t.)

A little after 10PM, Scott enters with an entourage and daps Ross. “Who got the weed?” he calls out, before sticking his head out of the dressing room and yelling into Webster’s VIP area, again, “Who got some weed?” Antony arrives soon after, cloaked in a long black cape and looking ever so slightly afraid. The singer heads straight to the bathroom after saying hi to Ross, then returns sipping a coconut water as Scott listens to music to get pumped up. “This nigga act like I’m James Blake, bruh,” Scott protests to an acquaintance, apropos of nothing. “I’m not James Blake.”

As this odd cast orbits around him, Ross remains entrenched on the couch, finalizing his setlist, eyes rarely lifting from his computer screen. A half-hour after he was supposed to take the stage, the setlist is, finally, in place. As he prepares to leave the room, Antony hovers in his direction and asks to takes a selfie with him. “I thought you wanted your shit top secret!” Ross says. “This is just for me,” Antony replies, softly.

The room mostly empties out. Antony kills the lights, grabs a bottle of Coke and a bag of pretzels, hides behind a curtain, and gazes out through a window onto a crowd of revved-up Hudson Mohawke fans. “What kind of audience is this?” Antony worriedly asks a friend. “I swore I wouldn’t do this, but only for Ross.”

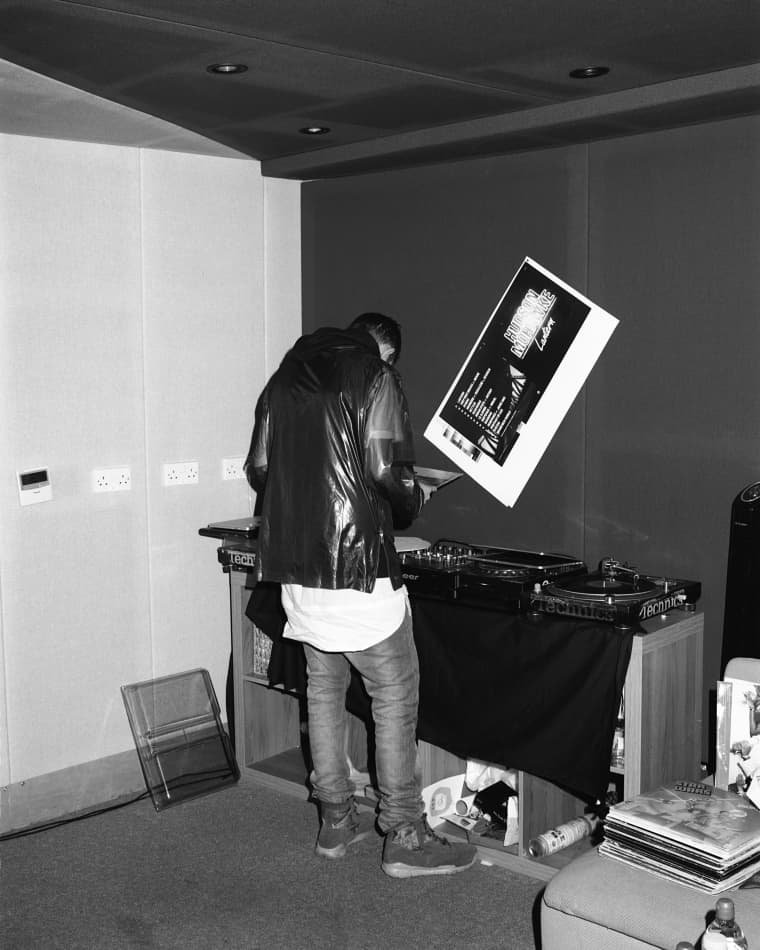

“I don’t want a poster of myself.”—Hudson Mohawke

Ross was raised in an artistic household, the oldest of four children. His mother is a drama teacher, while his father is a BBC host with acting credits in films like Hanna, 1408, and The Dark Knight. It was through his dad that he met the legendary, late radio host John Peel at a young age: “He was always one of my heroes because he was the only person on Radio 1 who’d get away with playing a hardcore rave track next to some fucking punk song,” he will tell me in London, a year after the Webster show. Growing up in the ’90s, Ross was too young to directly take part in the golden age of hyper-speed, decadent dance music in the UK, but he tried regardless. At nine years old, he got the logo of the Scottish rave Rezerection shaved into the back of his head. “My mom was like, ‘What the fuck have you done?’” he remembers.

For her part, Ross’ mother, Marie, says the head-shaving incident wasn’t “anything that concerned me.” She describes him as “a quiet, shy boy who was always very modest about everything. A decent wee boy.” Like most children, he enjoyed playing with Legos, but his creative impulses elevated the activity beyond normal playtime standards. “I remember him looking at a luxury holiday coach that had come from Amsterdam. We were driving in my dad’s car beside it, and Ross was fascinated by it. When we got home, he went straight inside and recreated the whole thing with Legos immediately.”

As a preteen, Ross was putting together hardcore mixtapes, compiled from tracks he recorded off the radio, with cover art he put together at the local copy store. He sold the tapes at local playgrounds, but the appeal was limited: “There weren’t too many 11- and 12-year-olds into happy hardcore,” he says. After his cousin gave him two hi-fi turntables for Christmas, Ross began to experiment with mixing, holing up in his room for five to six hours a day after school and performing a few preliminary gigs at an internet cafe in Glasgow. Eventually, he began sneaking into clubs. “I wouldn’t go to party,” he recalls. “I’d just sit there and study the DJs.”

As his tastes matured, he found himself increasingly drawn to hip-hop. “I discovered that most of the people making hardcore were hip-hop guys too,” he says. “They would take uncleared samples from hip-hop records, speed up the vocals, chop up the drums, and turn them into dance music. Hardcore and hip-hop didn’t seem that different.”

Taking inspiration from A-Trak, a Canadian turntablist who won the 1997 DMC World DJ Championships at the age of 15, Ross began competing himself as DJ Itchy. In 2000, when he was 15, he became the youngest entrant to place as a finalist in the UK DMCs. “It was quite a big deal back then, but by the age of 17, I was like, ‘Fuck this,’” he says. “[Turntable competitions] became more about technicality than about the original idea of DJ-battling—getting the crowd on your side.” He also wanted to avoid being pigeonholed as a one-trick artist. “I’d see all these people win world championships and get a nice golden jacket, and then it was like, ‘Now what? Where are they now?’ I can count the people who were champions of the world and actually still have a career on one hand.”

Ross’ transition from spinning to making records was aided by Playstation games like MTV Music Generator, which provided rudimentary production software before he had access to a personal computer at home. After his family acquired their own PC, he began working off a cracked copy of Fruity Loops, the program he still uses today. His first release as Hudson Mohawke was a self-released promo cassette of edits titled Hudson’s Heeters. It skewed close to his cut-and-scratch hip-hop roots and eventually made its way across the pond to gain the attention of Los Angeles beat scene mainstays like Flying Lotus and the Gaslamp Killer.

As Ross proceeded to churn out releases for labels like LuckyMe and Werk Discs, his close friend Callum Morton—then an employee at Warp—brought his material to the influential electronic label’s attention. Warp signed Hudson Mohawke in 2007. “My initial thought was, ‘Why the fuck would Warp want me?’” he says with a chuckle. “It didn’t seem like my sound particularly fit their aesthetic. I was like, ‘You’re gonna put me on the same label as Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada, and all I have are these little songs I made in my mum’s basement.’”

Warp A&R head Stephen Christian, however, draws a straight line between the label’s ’90s emergence and more recent signees such as Flying Lotus, Rustie, and Hudson Mohawke. “You go back to Autechre, Aphex, and Squarepusher—all the guys you think of as Warp OGs—and they’re so intensely influenced by hip-hop,” he says over the phone from the label’s London office. “For guys like Hudson and Rustie, there’s less of a separation between the music they’re making—which is completely left-field and weird—and the Drakes, Kanyes, and Kendricks of the world. There’s a natural conference point where their music and the mainstream meets.”

Hudson Mohawke’s first full-length with Warp was 2009’s Butter, an album that sounds like someone threw records from Goodie Mob, George Clinton, Cameo, Herbie Hancock, and Flying Lotus into a cauldron, pressed the melted vinyl to wax, and sampled the results. “Hopefully,” Christian says, “there are some kids who hear it and think, ‘This is the record André 3000 might’ve made if he was from Glasgow and did a bunch of drugs.’” Ross’ rear-view mirror is slightly more cracked: “When it came out, people were like, ‘What the fuck is this bullshit?’” he says with a sheepish grin. “It’s very all over the place, but that was the record I wanted to make then. People talk about that record more now than they did when it came out.” And with good reason: the album’s willfully weird streaks of purple soul and cybernetic funk were a bit off-trend back then, but they feel unbelievably current in the more R&B-friendly world of electronic music’s past few years.

More than any other sonic trend, though, the genre with which Hudson Mohawke’s name has come to be most closely associated is trap. It’s an association he’s still trying to live down, dating back to 2011’s Satin Panthers EP, a five-track collection of wobbly beats, razor-sharp synths, and pummeling low-end that still gets prime real estate in Hudson Mohawke sets. In 2012, he formed a group called TNGHT with the Montreal producer Lunice, and their self-titled EP still stands as a lightning-in-a-bottle moment that many have since tried (and failed) to recreate for themselves.

“Nobody knew what the fuck it was or how to categorize it,” Ross says of the initial response to the release. Trap, as a specifically dance-oriented genre, was anointed, and still thrives as a festival staple. For Ross, the success of TNGHT was overwhelming, and not entirely welcome. “We’re not really EDM guys,” he says, referring to himself and Lunice.

“I love that stuff, but you find yourself in the same lineups with bigger crowds where more and more people just want to hear one thing, and that’s not what I want to be about.” The increasingly aggressive attitude of TNGHT’s audiences didn’t help, either. “It’s fun to watch a huge mosh pit where everybody runs all over the fucking place,” he says, “but then the music becomes secondary to people thrashing each other. It’s too boring.” TNGHT attempted to swat away their given genre tag by opening shows with “Trap Funeral,” a version of Chopin’s “Funeral March” re-created with a low-pitched MIDI voice intoning the word “trap” like a Gregorian chant. Invariably, though, they’d end up playing what the crowd wanted to hear.

“You have to take care of yourself. Otherwise, you’re going to be six feet under.”—Hudson Mohawke

Their own reservations aside, TNGHT became ubiquitous on the international festival circuit, a constant grind made even more grueling when combined with Ross’ other high-profile gig at the time: working as one of the many cooks in Kanye West’s proverbial kitchen, beginning with 2013’s genre-busting Yeezus.

Ross came in contact with West’s team after BBC Radio DJ Benji B passed his music their way in 2011. “I’d been fucking trying to get a hold of them forever,” Ross says. “You never know if the music’s actually being passed on.” The referral brought him to a swagged-out London hotel—“one of those regal, fancy places with gold Egyptian cats”—where he plugged in his laptop and blasted his beats for West and his stable of writers. “I was shitting myself,” he says. Virgil Abloh, fashion designer and longtime creative advisor to West, described Ross to me during a phone conversation as a “shy, maximum creative type” in a room full of outsized personalities. “He came in by himself, a kid with his jacket still on, huddled around his laptop,” Abloh says. “He didn’t seem completely comfortable, but he played some music that blew the speakers away. Everyone was captivated.”

Ross’ ongoing partnership with Kanye’s G.O.O.D. Music label—which involves production work separate from his own solo endeavors—sounds like something of a musician’s dream. “I have the freedom to keep doing my own shit, and when a major project is being worked on, I can dip into that and be involved,” he says. And when he does, he’s increasingly mindful to operate under the code of secrecy that the camp keeps: “I’m always very wary of going into too much detail talking about the situation,” he says. “It’s just a sort of thing you don’t talk about.”

As the Yeezus sessions went on throughout 2012, though, it became harder for Ross to keep a secret of his own: a habit of recreational drug abuse that would eventually land him in the hospital. He recalls a recording session where “I had these really strong pills and had basically chewed up my lip until I had literally opened a hole inside of my mouth.” Another night, he choked while passed out, after ingesting a cocktail of opiates, xanax, and alcohol. He spent a week in the hospital after friends noticed he was turning blue. “Had I been alone, I wouldn’t have survived,” he says.

He spent his hospital stay itching to get back to the studio, and says the situation was dire enough to teach him some hard-earned lessons. “It was one of those points where I learned that this wasn’t a big joke. Like, if you want to do this, you have to be serious about it,” he says with body language—eyes glued to the floor, a slightly quicker pace of speech—that suggests a growing discomfort with the topic. “You have to take care of yourself. Otherwise, you’re going to be six feet under.”

These days, perhaps owing to these concerns about his health, Ross is not in a hurry to get anywhere particularly fast. When I arrive in London in mid-April—a full year after we first met in NYC—we’re supposed to link up at his current studio workspace, an underground den in London’s posh Soho area where he polished off his new solo album, Lantern (out in mid-June via Warp) and helped mix Kanye West’s recent single, “All Day.” But after a series of delays, I post up at a nearby pub. Ross apologizes over text and advises me to keep an eye out for a guy to whom he owes five thousand pounds.

During our visit, the schedule is relatively straightforward. Ross typically arrives at the studio around noon. His close friend and roommate Dominic Flannigan—head of Scottish label LuckyMe and also the creative director for Lantern—and I hang around as Ross intermittently works for eight hours or so, working on beats for Pusha T’s new album, sending stems to Boys Noize and Mark Ronson, and watching Tim & Eric videos on YouTube. After grabbing some dinner and drinks in the area, we hit up a nearby grocery store for drinks and sweets; a particular haul during a late-night Tesco’s run involves three chocolate-loaded Krispy Kreme donuts, a bag of Smarties cookies, a fifth of vodka, several large bottles of Peroni—and, naturally, heartburn medicine.

While Ross works, last-minute meetings with managers are bemoaned. A wave of relief is felt when the live drummer for the upcoming Hudson Mohawke U.S. tour agrees to drop by to talk about gear rather than meet at a music store. Another journalist’s phone interview is pushed back for a third time after Ross suggests, facetiously, to “tell him to fuck off.” In his mind, press opportunities and career-strategizing sessions feel like distractions. This doesn’t make him seem like a bad person, or like a hermetic genius, either—he’d just rather be making tracks.

Ross’ renewed focus is partially owed to learning how to say “Yes” less and “No” more, even when his choices seem inherently curious. While in high demand, TNGHT was put on hiatus at the end of 2013; Ross says he and Lunice are still swapping tracks, and that they’ll return at some point, but the break from the demand of touring—one that only grows more insistent as EDM’s festival-crazed economic bubble continues to inflate—is creatively necessary. “We were getting offers that would’ve been very rewarding financially,” he says. “But we were like, ‘If we pursue this, it’s going to be at the expense of the solo careers that we’ve had for the last ten years.’”

Lantern, which he recorded over a dedicated six-month period, sounds nothing like TNGHT’s skeletal, razor-sharp boom-clap. Ross has produced for the most vital figures in hip-hop, but on Lantern there are no rappers in sight—a conscious decision to avoid being pigeonholed as a “rap producer.” Granted, the album isn’t entirely divorced from hip-hop—its monstrous single “Ryderz” recalls the hyperspeed soul of College Dropout-era Kanye—but its sonic boundlessness is the thing that hits you the hardest. Twinkling orchestral ambience, gospel choirs, and heartbreaking balladry add light to Lantern’s kaleidoscopic glow, with piles of twisting synths—the presence of which are quite possibly the closest Hudson Mohawke comes to possessing as a stylistic calling card—providing the extra gas. Guest spots from Miguel (“Deepspace”) and Jhene Aiko (“Resistance”) reveal a more tender side of Ross’ production style, possibly the reflection of a softer side of himself.

Where he goes from here is anyone’s guess. One night, at 1AM, Ross dives into an endless-seeming vault of unreleased productions that he’s already considering for Lantern’s follow-up. He plays a track with a perpetual swell of cowbell and snaking synth, backed by drums that smack like storm waves against a lighthouse. “Play it until the drop?” Flannigan asks cheekily. “Don’t fucking talk about drops,” Ross responds, his tone as mildly playful as it is totally serious. Later, he unleashes a naked-sounding vocal cut he recorded with Antony, with the singer intoning the words I don’t love you anymore over a background of ominous synths. A pulsing bassline creates a feeling of anxious irresolution, quite the opposite of the punishing low-end Hudson Mohawke fans have come to expect.

As Ross continues to trawl through hard drives, Flannigan—whose duties for Warp include being the project manager for Lantern—works on setting the promo plan for the album in a piecemeal fashion. A casual brainstorm about

a remix contest for “Very First Breath” culminates in enthusiastic fits of laughter. While Flannigan has Ross’ attention, he asks him to consider a promo snipe: a full-profile shot of Ross, standing against a backdrop of darkness. “I don’t want a poster of myself,” he says, with zero reservation but not a trace of anger, before turning back to his computer, suddenly seeming to forget that there’s anybody else in the room. “Fuck that.”