Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

Curtis Stephen keeps a low profile, both online and in person. He prefers it that way. He barely uses Twitter, and he doesn’t even own an iPhone. Instead, he lets his work speak for him. Stephen can trace his journey as a reporter back to one particular story that kick-started his career. A story that was bigger than he could imagine at the time.

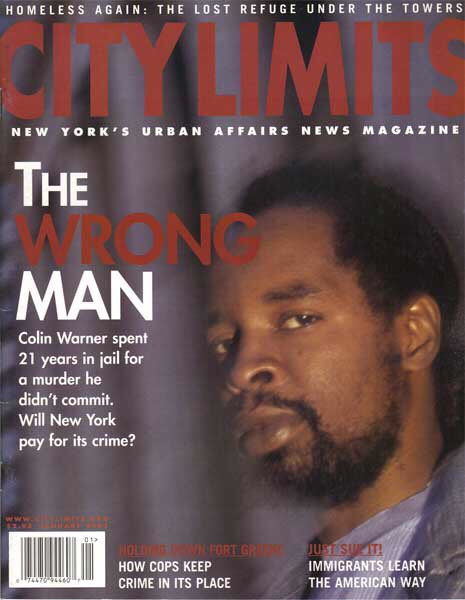

The piece was about Colin Warner, a Trinidadian immigrant to Brooklyn who was wrongfully accused of murder. Based on unreliable eyewitness testimony, Warner was imprisoned for 21 years for the death of 16-year-old Mario Hamilton in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. He was eventually released early in 2001 thanks to investigative help from a loyal friend, Carl King. In a cover feature for the New York-based magazine City Limits, in December 2001, Stephen told their story.

Colin Warner’s ordeal was eventually translated to the big screen, in a film called Crown Heights, released this August. Directed by Matt Ruskin, it stars LaKeith Stanfield as Warner and ex-NFL cornerback Nnamdi Asomugha plays his dedicated friend Carl King. On the occasion of its release, Stephen told The FADER about the eight-month experience of reporting and writing the article that was pivotal in inspiring the film.

CURTIS STEPHEN: The murder happened not terribly far from where I grew up. I found about it through my eldest brother, Mervyn Simon. He had a friend named Owen Rezende that was communicating with Colin Warner and received letters from him while he was in prison, describing his plight, so he knew the whole history of the case. I had graduated from Long Island University maybe two years before then. We went to his house, sat down, went through all the letters, and he told me about the case. At that time, Colin Warner’s wrongful conviction had become public knowledge. New York 1 had done the jailhouse interview with him, so we watched that.

My brother was always on me about covering stories that were about our people, people of color, but also from an immigrant perspective. My whole family is from Trinidad, Colin Warner is also from Trinidad, so that went through his radar early. My brother was all about social justice, and he was kind of like my executive producer. He passed away in 2009, but he was always somebody who was keen on telling me, “Curtis, take a look at that, look at this. You should cover this.”

Before that, I had only done a very generic bookstore story for City Limits. So coming out of that conversation, I had agreed to try and attempt to pitch the story. I had pitched it to a couple magazines that said no. I went to Barnes & Noble and saw City Limits on the newsstand and remembered their commitment to social justice issues. I wrote a letter — to describe the world then, I did not own a cellphone, I did not own a personal computer — but I wrote a letter to the editor, and she got back to me and said, “What an amazing story.”

The initial reporting around Colin Warner’s case had really just focused on the fact that he was wrongfully convicted. There was some mention of him having a friend who had helped, but the attorney of record was seen as the one who [helped exonerate him]. I was so struck by that, like, Wow, he had a friend who worked on this case who was also from Trinidad. So I pitched it with the idea of here was this man who was so committed to his friend, and let's look at it with a deeper focus.

I met [Colin] in March of 2001, so that was two months after he came out of prison. We did an interview at Grand Army Plaza because that was where my ‘office’ was. I was very nervous because I just didn’t know what mental state he was in. Again, he had done the New York 1 interview but the nature of this was very different. And that [nervousness] went away within 20 seconds of meeting him. It was the familiarity of meeting somebody who understood what being from Trinidad and what the immigrant experience was like, and him having to be in prison. As somebody who is a Rastafarian, to be a Rastafarian back then was almost treated as, like, Bloods and Crips. It was seen as a threatening thing.

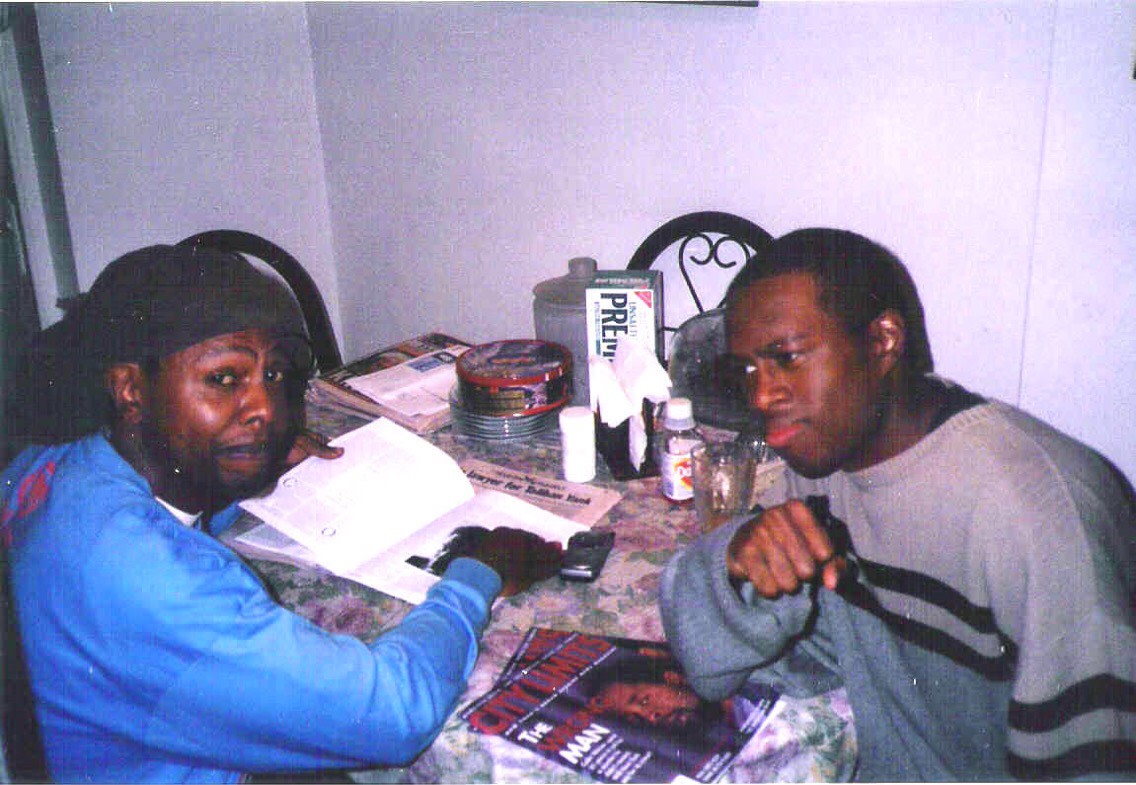

Curtis Stephen and his brother, Mervyn Simon.

Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

Curtis Stephen and his brother, Mervyn Simon.

Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

“It sounds so unbelievable that somebody could spend 21 wrongful years in prison.”

I never wrote a story like this before. This was 4,000 words, and it just kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger than I even realized. I kept having to go back and ask other questions. He kept joking, "Oh you always have one more question." But it was to make the story more in depth, so we kept spending more time together as a result of it — both Colin and Carl King, his best friend. So in the course of that, we were spending more time, we'd go get some rotis, and talk more. It was a very organic sort of thing. There are all these moments where we were having to spend time together beyond us just working on the story. You get to find out what's at the core and the center of the man.

I've interviewed people who had also been wrongfully convicted, who are difficult to deal with in terms of their disposition because they're still dealing with the experiences of that. And that's not to say that Colin himself is not. But I think I was able to, based on our familiarity, get a different side of him really. He had a mission. He was definitely candid. He told me about how whenever he hears keys jingle, how that sets off his mind in a different way than us, because for him it takes him right back [to prison]. I had to realize to let him go, give him time, and be patient. I think it was a crazy time for him too because after the sort of initial attention of, "Okay he's out," he was sort of processing trying to fit back into this world. And I wanted to give him time to do that.

Carl [King] was the one who was the key negotiator for me through the story. He had the trial transcripts that he personally maintained. He was able to help me get access to key people in the story which was helpful. But also, got to spend time with him and get the stuff that, while it's not in the story, it creates the atmosphere for the story. To really get a sense of what type of person was willing to give up his time to me to share that. He didn't live too far from me, so we got to see each other a lot in that way. He very much came on like a big brother role.

In 2000, just before this [story], I was living in Atlanta, working for CNN. And I was wrongfully detained by police. I was walking one night going to buy roti. I was surrounded by police who grabbed me, detained me, and put handcuffs on me. One officer threatened to kick me in the face until they determined my identity. And then they saw my CNN ID card, and then they took the handcuffs off. The interaction changed to, "Sir, I asked you for identification and you didn't give it to me." It changed from me being an aggressive threat to me being an idiot.

What that taught me really was how somebody completely and innocently ends up in the criminal justice system. I was just walking out of the store and walking home, and all of a sudden surrounded by police officers, grabbed, and detained. Just like that. There were no words at all. It sounds so unbelievable that somebody could spend 21 wrongful years in prison, like, How could that happen? Very easily.

(L-R): Carl King, Curtis Stephen, and Colin Warner.

Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

(L-R): Carl King, Curtis Stephen, and Colin Warner.

Courtesy of Curtis Stephen

“Even if you say 1% of the people who are incarcerated in this country are wrongfully convicted, you’re still talking about thousands and thousands of people.”

Colin’s case is unique, in a sense, because a lot of wrongful conviction cases we see involve DNA evidence. They find a bloody knife, they test it and say, “Based on this evidence, your DNA is not on this, you couldn't possibly have committed this crime, we're letting you out.” That's the way the system is, in effect, designed. But in this particular case, there was no bloody knife, there was no bloody glove per se, so here's somebody who had to go out and reinvestigate the case on his own. There aren't that many groups that are focused on cases like Colin's where it was based on eyewitness identification, where there is no DNA evidence to be tested.

So you can imagine, even if you say 1% of the people who are incarcerated in this country are wrongfully convicted, you're still talking about thousands and thousands of people. And they're sitting there languishing, wondering. After I wrote this story, I was starting to get letters from people who were wrongfully convicted saying, "Take a look at this case." And it's a very difficult thing because what resources do I have to reinvestigate cases in that way? It can be a very frustrating thing. Advocates having been pushing for a whole series of reforms in light of the whole series of wrongful convictions cases that we've seen, in terms of videotaping. Not just videotaping police interactions with the public in arrests, but interrogations that take place. Because there's a whole psychological apparatus between a police officer interrogating a witness or a non-witness.

I still see my job as I did then: shining a mirror. If you think about what that really means, there's a great deal duty behind it, right? Because again, here's a case that did fall into the public sphere. The man was wrongfully convicted, but there's so much that we didn't know. Why was a man incarcerated for 21 years? And what did it take to get him out? The point is we've so many stories where somebody comes out, you discover that they're wrongfully convicted, they have the press conference, they say, "I'm so glad to be out, I'm not bitter." And then they disappear. You don't hear anything about them, you don't know why it happened, you know what happened to them since. But also in terms of their own consciousness and what that means as a human being to have gone through that. So that was the whole focus of the story as well: to really shine a light on this particular individual and what that says about the system overall. I don't think you have to become an advocate as a journalist to do that, you just have to do your job.

As time was going by, over the years, I was discovering more wrongful conviction cases. You hate to say how routine it became. At the time it was sort of an eye-buster, like, How could this happen? You can check almost on any given day, and somebody who was wrongfully convicted could come out, unfortunately. You've heard of cases where a guy's come out after 30 years in Mississippi or Louisiana something. What stood out in this case was the measure of the dedication of this friend on the outside reinvestigating this case. That stood out a great deal to people.This measure of fighting back, taking on the system, trying to reclaim a measure of dignity while this person was dealing with such degradation, and his wife out there supporting the whole time.

When I met Carl King, I think about a man who had no formal education in the criminal justice system, he didn't go to law school or anything. This is a man who saw his friend end up in the system, and took upon himself to study and learn in a very practical level, of how he can deal with the criminal justice system. And [he] was working his way around it without a formal law degree. I think you can be inspired by [that] and realize that the system, as we call it, is not any bigger than us.